Last Aid Courses as measure for public palliative care education for adults and children—a narrative review

Introduction

The purpose of this narrative review is to provide a narrative overview of the existing literature on Last Aid Courses (LAC) in the context of public palliative care education (PPCE), to reflect on the feasibility and acceptance of the same and to present the first authors and other experts experiences from the implementation process of LAC in different countries.

In the future, there will be an increased need for palliative care in the community because of the wish of many people to die at home and a rising number of elderly and people with co-morbidities (1-3). However, despite the wish to die at home, many terminally ill patients end up dying in hospitals, hospices, or nursing homes (4). This discrepancy has been the subject of a review that revealed seven major barriers to home deaths (5). Three of these barriers are associated with a lack of knowledge about palliative care; lack of knowledge, skills and support among informal carers and healthcare professionals; informal carer and family burden and recognising death (5). Therefore, acknowledging and addressing barriers to home deaths and adopting a public health awareness approach to basal palliative care education is pertinent to managing and facilitating community palliative care and home deaths now and in the future. PPCE has its roots in a public health strategy by the World Health Organisation (WHO), which promoted the integration of palliative care into all layers of society (6). It involves teaching and empowering citizens about death, dying and informal care for dying people as part of a public health palliative care approach. There is a growing need for awareness of palliative care, death literacy and PPCE in the public (7-10). However, PPCE remains a challenge and needs to evolve from just ‘raising awareness’ to ‘educational interventions’ based on large scale public health approaches (11). Concrete initiatives to teach the public about basic palliative care are scarce. Although, in recent years programmes such as Compassionate Communities (12) and Last Aid (13,14) have been doing just that. The Last Aid project is an educational programme that teaches citizens about basic palliative care and has spread to several countries worldwide (13,14). The target group of the Last Aid project is the general public. Therefore, LAC are offered to all interested adults teenagers and children. LAC may play a role in the development of personal skills strengthening community action (15). Most recently, due to the current COVID-19 pandemic, the LAC has been adapted to provide PPCE online (16,17). The pandemic appears to have contributed to a rising public awareness of death, including a growing interest in talking about death and dying. As an emerging initiative in the field of PPCE in recent years, there is a need to map the growth and progression of educational approaches for the public such as LAC. Therefore, this paper will collate recent publications and examine Last Aid and its implementation in various countries from a public health context. We present the following article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-762).

Methods

This article is a narrative review of the existing publications on LAC and PPCE that was based on a invited lecture presented by Bollig during the Online Summit on Palliative Care and Medicine ICPCM in December 2020 (18) and the first author’s and other experts’ experiences with the implementation of LAC in several countries. The methodological approach chosen was a narrative literature review (19). A literature search with the MeSH (Medical Subject Heading) terms “palliative care education” and “public” plus the term “last aid” was performed in PubMed and Medline, years searched from 1975 to present (May the 26th 2021). Other additional sources were found by hand searching, books, reference lists and the internet. Table 1 provides an overview of sources used for this narrative overview. In addition, the experiences from the implementation process and the findings from the scientific literature will be summarised. Selection criteria used were as follows: Articles in English, German, Norwegian, Danish, and Swedish that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included. Inclusion criteria: Only publications that had PPCE for citizens as their major topic were included. All other publications were excluded. A short overview of the existing literature on this topic is provided and discussed. The findings from the literature search and experiences from the implementation process are presented under thematically arranged subthemes. The methods used for data collection, analysis and reporting follow recommendations for narrative literature reviews proposed by Green, Johnson, and Adams (19). Reporting is performed with reference to the narrative review checklist (19).

Full table

Discussion

A summary of the findings from the literature and the first author’s and other experts’ experiences from the implementation of LAC in various countries are presented under thematically arranged themes. An orienting literature search in PubMed using “last aid” led to 6 results only, including a paper on the effects of a nuclear blast and only two papers were connected to the LAC (13,17). A search strategy combining “palliative care education” and “public” led to 69 results in PubMed. Fifty-six of these were published within the last 5 years. Of all results, screening of the abstracts showed that only six of these articles were related to palliative care education of the public. The main finding was that there were relatively few scientific articles dealing with PPCE or models to provide palliative care education for the public found in the literature. The LAC is an example for an educational concept for the public that has been implemented in a number of countries round the world (13,17). LAC for the public were first described by Bollig in 2008 (13,18,20).

The results are presented thematically using the following headings: (I) need for PPCE (PPCE) and current approaches to PPCE; (II) the Idea of Last Aid, the public knowledge approach to palliative care and its implementation in different countries; (III) lessons learned from the scientific evaluation of the LAC.

Need for PPCE and current approaches to PPCE

The scientific literature on palliative care education focuses mainly on the need to educate healthcare professionals, whereas PPCE seems to be a neglected topic. Several authors have described a lacking awareness of palliative care in the general public and many recommended palliative care educations of the public (9,10,13,15,21-28). Unfortunately, personal experience is still one main source for people’s palliative care knowledge (28) and many home caregivers had unmet information needs (29). Available information for citizens lies often above the literacy level of the general public (30). This underlines the importance of PPCE lying within the general literacy level of citizens using an easy to understand language. One example of an initiative to introduce a culturally adapted form of PPCE is seen in First Nations communities in Canada where open meetings, workshops and bedside education were employed (31). First aid education in many countries is public knowledge and a part of the school curriculum. In Europe, recommendations for first aid are based on an international consensus from the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) that is updated on regular intervals and published as guidelines in scientific journals (32). So far, palliative care is not an essential part of public knowledge or the school curricula. The public knowledge approach to palliative care seeks to implement basic knowledge about death, dying and palliative care to public knowledge by establishing LAC for the public and trying to include them in the school curricula (13,20,33,34). Some approaches to educate the public in different countries are reported in the literature (31,35-41). These include both informal meetings like the “death chat” at St. Christopher’s hospice in London (35) and an approach called “death cafe” that is offered in 76 countries round the world (36). In Australia, psycho-social group education for family carers has been found useful as preparation to provide palliative care (37,38). According to Kellehear, palliative care is everyone’s business (12) and there is a need to establish national and international educational programs to improve both health literacy and death literacy (39). As death literacy includes the four parts—skills, knowledge, experiential learning, and social action (39)—education only is not enough, and both reflection and social action are needed. Education should be accompanied by a reflection on attitudes, as well as action. In order to enable reflection, places for open discussions about death and dying, like the death cafe (36), the LAC (13,33,34) or online education programs about death and dying, such as the Massive open online course around death and dying (40,41) and the Online LAC (16,17) are needed. To raise public awareness for the topic an annual World Last Aid Day has been proposed by Mills et al. (15) in order to promote the development of personal palliative care skills and to improve community action.

The Idea of Last Aid, the public knowledge approach to palliative care and its implementation in different countries

The idea of a LAC for the public was born between 2005 and 2008 and was first described by Bollig in a master thesis at the University Klagenfurt-Vienna/IFF in Austria in 2008 (13,18,20). This thesis was published as a book in 2010 (20). The first idea included the so-called public knowledge approach to palliative care utilizing LAC to educate the public about palliative care and to provide an open space to discuss and reflect death and dying in general (20). The main aim of this approach is to educate the public using a short LAC of 2–4 hours that should be implemented in the public school education system and offered for all interested people in different settings throughout society. Public education may support both the introduction of a basic palliative care knowledge; improving people’s willingness to talk about death and dying, as well as encouraging participation in the provision of end-of-life care. In the future, this could contribute to making home death possible for more people who want that and could improve the public debate about death and dying. Furthermore, lessons learned from LAC might also inform people who support dying in nursing homes, hospices or hospitals and inform the public debate on death and dying. Table 2 shows the initially suggested topics for the LAC (20).

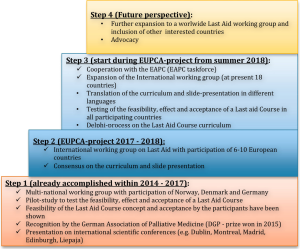

After describing the idea of LAC, working groups were established to discuss the curriculum and structure the future LAC (33,42,43). The first pilot courses were held in Hyllestad in Norway (November 2014), Schleswig in Germany (January 2015) and Skive in Denmark (April 2015). The pilot LAC in these three countries were very well accepted by the public and received much attention in the media. In Germany, LAC received a prize for Palliative Medicine from the German Association of Palliative Medicine (44) and was awarded as one of the best social projects in 2015 by start social and Chancellor Angela Merkel (45). The founder, Georg Bollig, received the Heinrich Pera Preis 2020 for the idea of LAC and the implementation work of LAC to bring hospice and palliative care philosophy into the society in Germany and other countries (46). Between 2017 and 2019 an International Last Aid working group with representatives from different countries and national organisations from e.g., palliative care, health-services, and religious institutions as cooperation partners was established. This international working group revises the curriculum and contents of the international LAC every second year. Scientific evaluation of LAC is coordinated by the international Last Aid Research Group Europe (LARGE) that was founded in September 2019. Following the initial success in three countries, the international dissemination of LAC was the aim of a project of the Leadership Academy of the European Palliative Care Academy. This project helped to spread LAC to 18 countries in Europe, Australia and South-America (14,47,48). The European Association for Palliative Care has started a taskforce on Last Aid and PPCE (49). Figure 1 provides an overview of the four steps of the development of the international Last Aid project.

The basis of the LAC concept is Last Aid as a learning concept including a regular international consensus meeting similar to the work of the European Resuscitation Council (ERC) and the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR) in the field of Resuscitation and first aid (32,50,51). The chain of survival from emergency care inspired a chain of Palliative Care (Figure 2) illustrating the cooperation between non-professionals and health specialists to ensure the best possible quality of life for terminally ill people (20).

The international LAC is based on a consensus about its curriculum and an international slide-presentation that is discussed and decided on during regular meetings of the International Last Aid working group. The last meeting and adaptation of the curriculum took place in October 2020 in connection with the 2. International Last Aid Conference that was held online with 174 participants from 18 countries (52). During these regular meetings, representatives from the participating countries adapt the Last Aid curriculum and presentation to the current evidence and state of knowledge. In addition to the international Last Aid working group with experts from the participating countries, the LARGE was founded in 2019 and coordinates research efforts by research groups connected to the Last Aid concept. Thus, Last Aid can be described as a learning system. Aiming to educate and enable the public to provide palliative care in the community the LAC can be seen as the basic public education program for compassionate communities. Therefore, everyone should participate in Last Aid training and it should be as normal as First Aid training for the public. It has been suggested to include LAC in the school curricula for children (33,34,53) and an annual international Last Aid day has been proposed by Mills et al. (15). The current version of the LAC consists of 4 modules each of 45 minutes duration. The four modules of the course include the topics end-of-life care, advance care planning and decision-making, symptom management, burial and cultural aspects of death and bereavement. An overview of the content is shown in Table 3. The contents include in module 1: an introduction to the dying process; the importance that everybody should learn and provide both first aid and Last Aid when appropriate. In module 2: basics of palliative care philosophy, information about local networks of support (physicians, nurses, hospices, palliative care teams, etc.) and role of compassionate communities; decision-making for medical and non-medical situations; advance care planning and power of attorney. In module 3: typical problems and symptoms at the end of life; practical Last Aid measures to relief suffering; to care for and to comfort seriously ill and dying people; eating and drinking at the end of life. In module 4: grief and grieving as normal parts of life; legal aspects of death and the funeral (death certificate; legal regulations of keeping a dead person at home; different types of funerals and burials); saying farewell; rituals that can support and help before and after death.

The course is normally held in a classroom setting with 6 to 20 participants within a timeframe of 3 to 4 h during one day (13). As a result of the COVID-pandemic online LAC have been started in Germany, Scotland and Brazil and are very much appreciated by the participants (16-18). LAC are led by two instructors/facilitators including for example nurses, doctors, social workers, volunteers, or others with experience from the field of palliative care (14). One of the instructors/facilitators must be a nurse or a doctor in order to be capable of answering medical questions from the participants according to the international binding course rules (14). The decision to hold the LAC by two instructors was based on the assumption that participants might show emotional reactions and the need for support may occur. The practical experiences and scientific evaluation have shown that people display a variety of reactions to the topics, including tears, but that the group members or the instructor without a need for professional help handles these reactions. Interestingly, many participants are very appreciative that the instructors facilitate the course as a team. There are some encouraging experiences from teaching special groups, such as police officers from Scotland and Germany and the entire staff of a university hospital in Germany.

Lessons learned from the scientific evaluation of the LAC

Along with the first pilot courses in Germany in January 2015, the scientific evaluation of the LAC began. An overview of scientific research papers on LAC for adults and children, as well as Online LAC, is provided in Table 4. It includes 5 publications (17,34,53-55) reporting prospective mixed methods studies that all evaluated the participants views on the LAC: 4 pilot studies addressing different participant groups (adults and children, medical professionals) surroundings (public classes and hospitals) and teaching approaches (classroom teaching vs online teaching) and so far, only one study designed as a prospective mixed methods multicenter study with 5,469 informants from three countries (54). The main findings of each study are included in Table 4. The main limitation for the four described pilot studies was a limited number of participants ranging from 52 to 156 participants. Another limitation was that the informants were asked about their views and experiences right after the course. Therefore evidence about the use of the acquired knowledge is lacking. At present studies with a longitudinal design to evaluate the long-term effects of LAC are planned or in the starting phase.

In general, LAC are open to all interested people. The pilot study included 55 adults from three LAC. People who had participated in a complete LAC with four modules, each lasting 45 minutes were asked to return a questionnaire with both quantitative and qualitative questions (34). 52 of 55 LAC participants participated in the study (response rate 95%). Interestingly 14 out of these 52 (27%) informants had medical professions. In a multicenter study with 5469 informants 9.4% had a medical profession (54). This shows that this group is interested in education about palliative care on a basic level. A pilot study introducing LAC for the entire staff of a university hospital, including both medical and non-medical personnel, showed that the LAC helped to reduce information deficits of the staff (55). One important reason for participation was feeling burdened by death and dying (55). Nevertheless, medical staff asked for an extended curriculum of the LAC in order to meet their educational needs (55). The first evaluation of the German pilot study was published in 2015 and received a prize from the German Association for Palliative Medicine (34,44). The pilot study showed that LAC were feasible and well accepted by citizens. All participants of the pilot courses stated that they would recommend the course to others (34).

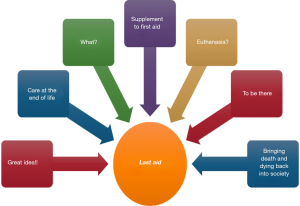

LAC for children and teenagers from 9–17 years of age were evaluated in Germany. It was shown that 85% of the participants had previous experience with death and dying and that they appreciated the possibility to talk about that topic in a group setting (53). Most participants found the course useful and would recommend it to others (53). A recently published multicenter study from Germany, Austria and Switzerland including 5,469 LAC participants as informants revealed that 88% of the participants were female with a median age of 56 years (54). It is, at present, unclear if the reason for that could be that this group is more engaged in caring for others. Future research should investigate the possible connection between the caregiver role and attendance at a LAC. The COVID-19 pandemic led to the first Online LAC in some countries such as Germany, Brazil, and Scotland. Online LAC were feasible but often described as second best choice only (17). Interestingly, the online format seemed to engage more younger people and people who had a caregiver role (17). The first author’s experiences with the implementation of LAC in many countries is in line with the results from the scientific evaluation. The course has been welcomed in many countries and seems to be feasible across different cultures and nationalities. The term Last Aid is usually understood for its similarity to first aid. Many people associate Last Aid with; a supplement to first aid at the end of life, care at the end of life and bringing death and dying back into the society (56). Only few people associate euthanasia with Last Aid. Some informants reported an irritation when hearing the term Last Aid the first time. Figure 3 illustrates the different associations people reported.

The above presented results show that the general public lacks awareness of palliative care and death literacy, highlighting an urgent need to establish public platforms to discuss death and dying and to provide basic and practical palliative care education to empower people and to enable them to participate in end-of-life care provision in the community (9,10,13,15,20-28). Approaches to improve the public discourse about death and dying and to raise awareness for public palliative care include different methods, such as open meetings to talk about death as for example the death café/death chat (35,36). Group meetings have been used in different settings in Australia and Europe to provide palliative care education (13,14,37,38,42,43). Online learning programs seem to be useful in order to reach many people over large geographical areas, such as rural Australia or during the present COVID-19 pandemic with restrictions imposed on group meetings and classroom teaching (16-18,30,40,41). Online LAC have been developed to address citizens’ needs to talk about death and to receive palliative care education during the pandemic. The experience with these online courses showed their feasibility and acceptability and the possibility to address groups other than those attending classroom teaching, for example younger people and caregivers who can not leave their home (16-18). To our knowledge, the LAC is, at present, the only educational initiative for the public that is offered as both classroom and online teaching model in a number of different countries and different languages (13,14). Work with LAC for PPCE is ongoing in 18 countries, for example Denmark, Germany, Slovenia, Lithuania, Scotland, Ireland, Australia, Brazil, etc. The overall results show that the LAC is feasible and very well accepted in many different countries, cultures and groups (13,17,33,53-55). LAC have been used for adults, children and groups such as hospital employees and police officers. LAC is also possible in an online course format, which was tested during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scientific work on cultural issues and the effects of LAC are ongoing in a number of countries. The LARGE coordinates international research and has already hosted two international Last Aid Conferences; one in Soenderborg, Denmark in 2019 followed by an online conference with 174 participants from 18 countries in 2020 (57). LAC have been recommended for the general public and a World Last Aid Day has been proposed to raise awareness for public health palliative care and end-of-life care in the community (15,58,59). In summary, LAC are feasible and well accepted by citizens in different countries (13,15,17,34,53-55). Caring communities and caring cities need an educational foundation that may be provided by the LAC or other approaches to PPCE (13,60). The LAC can contribute to a public debate on death, dying and palliative care and may contribute to empowering citizens in providing end-of-life care. The Last Aid project is considered to be a learning system that incorporates active participation in knowledge creation and public action and cooperation between citizens, experts, researchers and policymakers. Research and international collaboration have been an integral part of Last Aid from the start. Future research should aim to investigate the effects of the LAC on participants’ motivation and ability to take part in end-of-life care and the long-term effects, including the possibility of increasing the likelihood of home death for those who choose it.

Limitations and strengths

An obvious limitation of the review is the limited number on scientific papers on the PPCE and especially the LAC. Although LAC has become widespread in a number of countries including Europe, Brazil and Australia, the international collaboration on the scientific evaluation of LAC was first established in 2019 when the LARGE was founded. This shows the need for further research on the topic. As the first author is the founder of the Last Aid movement, this can be considered as both a strength of the paper—due to the insights from the implementation process right from its commencement—and as a limitation, as he is also is the first author or co-author of the scientific articles on Last Aid that have been published up until now.

Conclusions

Measures to raise awareness of palliative care, to improve the public discussion about death and dying and to empower citizens to participate in end-of-life care in the community are needed and should be offered more widely. Various approaches for PPCE have been described in this article. LAC are one example of a feasible and well-accepted approach to PPCE in different countries. The LAC can contribute to a public debate on death, dying and palliative care and may contribute to the empowerment of citizens in the provision of end-of-life care. Further research on PPCE and LAC is necessary to add to the body of knowledge in this emerging field and is ongoing at present.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Annals of Palliative Medicine for the series “International Conference on Palliative Care and Medicine”. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-762

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-762). The series “International Conference on Palliative Care and Medicine” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. GB owns the trademark Last Aid, is a board member of the German non-governmental organization Letzte Hilfe Deutschland gUG. He receives financial compensation as lecturer and trainer for Last Aid Instructor courses. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gomes B, Higginson IJ, Calanzani N, et al. Preferences for place of death if faced with advanced cancer: a population survey in England, Flanders, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal and Spain. Ann Oncol 2012;23:2006-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, et al. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet 2013;381:752-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Etkind SN, Bone AE, Gomes B, et al. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med 2017;15:102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nilsson J, Blomberg C, Holgersson G, et al. End-of-life care: Where do cancer patients want to die? A systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol 2017;13:356-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wahid AS, Sayma M, Jamshaid S, et al. Barriers and facilitators influencing death at home: A meta-ethnography. Palliat Med 2018;32:314-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief and palliative care. Technical report series 804. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1990. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/publications/en

- Larsen AMN, Neergaard MA, Andersen MF, et al. Increased rate of home-death among patients in a Danish general practice. Dan Med J 2020;67:A01200054 [PubMed]

- Gágyor I, Himmel W, Pierau A, et al. Dying at home or in the hospital? An observational study in German general practice. Eur J Gen Pract 2016;22:9-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McIlfatrick S, Hasson F, McLaughlin D, et al. Public awareness and attitudes toward palliative care in Northern Ireland. BMC Palliat Care 2013;12:34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gopal KS, Archana PS. Awareness, knowledge and attitude about palliative care, in general, population and health care professionals in tertiary care hospital. Int J Sci Study 2016;3:31-5.

- McIlfatrick S, Slater P, Beck E, et al. Examining public knowledge, attitudes and perceptions towards palliative care: a mixed method sequential study. BMC Palliat Care 2021;20:44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kellehear A. Compassionate communities: end-of-life care as everyone's responsibility. QJM 2013;106:1071-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bollig G, Brandt F, Ciurlionis M, et al. Last Aid Course. An Education For All Citizens and an Ingredient of Compassionate Communities. Healthcare (Basel) 2019;7:19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Last Aid - Mills J, Rosenberg JP, Bollig G, et al. Last Aid and Public Health Palliative Care: Towards the development of personal skills and strengthened community action. Prog Palliat Care 2020;28:343-5. [Crossref]

- Bollig G, Knopf B, Meyer S, et al. A New Way of learning End-of-Life Care and Providing Public Palliative Care Education in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic–Online Last Aid Courses. Arch Health Sci 2020;4:1-2.

- Bollig G, Meyer S, Knopf B, et al. First Experiences with Online Last Aid Courses for Public Palliative Care Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Healthcare (Basel) 2021;9:172. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bollig G. Public Palliative Care Education: Experiences with Last Aid Courses for adults and children including Online Last Aid Courses during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. Abstract Online Summit on Palliative Care and Medicine ICPCM-2020. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Ph99Ek78QY

- Green BN, Johnson CD, Adams A. Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: secrets of the trade. J Sports Chiropr Rehabil 2001;15:5-19.

- Bollig G. Palliative Care für alte und Demente Menschen Lernen und Lehren. LIT-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2010. Available online: http://www.lit-verlag.de/isbn/3-643-90058-6

- Westerlund C, Tishelman C, Benkel I, et al. Public awareness of palliative care in Sweden. Scand J Public Health 2018;46:478-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kozlov E, McDarby M, Reid MC, et al. Knowledge of Palliative Care Among Community-Dwelling Adults. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018;35:647-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Partridge AH, Seah DS, King T, et al. Developing a service model that integrates palliative care throughout cancer care: the time is now. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3330-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singer PA, Wolfson M. The best places to die BMJ 2003;327:173-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edwards SB, Olson K, Koop PM, et al. Patient and family caregiver decision making in the context of advanced cancer. Cancer Nurs 2012;35:178-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dellon EP, Helms SW, Hailey CE, et al. Exploring knowledge and perceptions of palliative care to inform integration of palliative care education into cystic fibrosis care. Pediatr Pulmonol 2018;53:1218-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boucher NA, Bull JH, Cross SH, et al. Patient, Caregiver, and Taxpayer Knowledge of Palliative Care and Views on a Model of Community-Based Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:951-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McIlfatrick S, Noble H, McCorry NK, et al. Exploring public awareness and perceptions of palliative care: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2014;28:273-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shalev A, Phongtankuel V, Reid MC, et al. Home Hospice Caregivers' Perceived Information Needs. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019;36:302-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prabhu AV, Crihalmeanu T, Hansberry DR, et al. Online palliative care and oncology patient education resources through Google: Do they meet national health literacy recommendations? Pract Radiat Oncol 2017;7:306-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prince H, Nadin S, Crow M, et al. "If you understand you cope better with it": the role of education in building palliative care capacity in four First Nations communities in Canada. BMC Public Health 2019;19:768. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zideman DA, Singletary EM, Borra V, et al. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines 2021: First aid. Resuscitation 2021;161:270-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bollig G. Palliative Care Education for Everybody. In: Mollaoglu M. Palliative Care. InTechOpen 2019. Available online:

10.5772/intechopen.85496 10.5772/intechopen.85496 - Bollig G, Kuklau N. The Last Aid Course – a means to improve Palliative Care in the community through information and education of citizens. German J Palliat Med 2015;16:210-6.

- Death Chat—Talking about Death and Dying Remains One of the Biggest Taboos within Most Communities. Available online: https://eapcnet.wordpress.com/2013/08/13/death-chat-at-st-christophers/

Death Cafe - Hudson P, Quinn K, Kristjanson L, et al. Evaluation of a psycho-educational group programme for family caregivers in home-based palliative care. Palliat Med 2008;22:270-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hudson P, Thomas T, Quinn K, et al. Teaching family carers about home-based palliative care: final results from a group education program. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:299-308. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Noonan K. Death literacy-developing a tool to measure the social impact of public health initiatives. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:AB007. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tieman J, Miller-Lewis L, Rawlings D, et al. The contribution of a MOOC to community discussions around death and dying. BMC Palliat Care 2018;17:31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miller-Lewis L, Tieman J, Rawlings D, et al. Can Exposure to Online Conversations About Death and Dying Influence Death Competence? An Exploratory Study Within an Australian Massive Open Online Course. Omega (Westport) 2020;81:242-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bollig G, Kuklau N. The Last Aid Course! A course for the public about death, care at the end of life and palliative care. Omsorg 2015;2:66-71.

- Wegleitner K, Heller A, Bollig G, et al. Living and helping until the end - to talk about dying - a curriculum to talk about life and death with citizens. In: Klaus W, Katharina H, Andreas H. “Zu Hause sterben – der Tod hält sich nicht an Dienstpläne”. Ludwigsburg, Germany: Hospizverlag, 2012.

- The German association for Palliative Medicine awards the recognition and sponsorship award for outpatient palliative care 2015 to Last Aid. Available online: https://www.dgpalliativmedizin.de/dgp-aktuell-2015/2015-09-25-08-29-33.html

- Startsocial 2014/2015. Kurzportraits der 25 Projekte in der Bundesauswahl. Available online: https://startsocial.de/sites/startsocial.de/files/downloads/files/startsocial_bundesauswahl_2014_15_0.pdf

Heinrich Pera Preis 2020 . Available online: https://www.hospiz-palliativ-zentrum-halle.de/heinrich-pera-preis/preisverleihung-2020/Georg Bollig-EUPCA - Bollig G. EUPCA Project report: Last Aid International – the Last Aid Movement. Implementation of an international working group on Last Aid. Berlin, Germany: European Association for Palliative Care, 2019.

- EAPC taskforce Last Aid and Public Palliative Care Education. Available online: https://www.eapcnet.eu/eapc-groups/task-forces/last-aid/

European Resuscitation Council International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation - International Last Aid Conference online 2020. Available online: https://lastaid.paliativa.si

- Bollig G, Pothmann R, Mainzer K, et al. Kinder und Jugendliche möchten über Tod und Sterben reden: Erfahrungen aus Pilotkursen Letzte Hilfe Kids/Teens für 8- bis 16-Jährige. (Children and Teenagers Want to Talk About Death and Dying – Experiences from Pilot-Courses Last Aid for Kids/Teens from 8–16 Years). German J Palliat Med 2020;21:253-9.

- Bollig G, Brandt Kristensen F, et al. Citizens appreciate talking about death and learning end-of-life care – a mixed-methods study on views and experiences of 5469 Last aid Course participants. Progress in Palliative care published online 25 Feb 2021. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09699260.2021.1887590

- Mueller E, Bollig G, Boehlke C. Lessons learned from introducing “Last-Aid” courses at a university hospital in Germany. Berlin, Tyskland: 16th World Congress of the European Association for Palliative Care, 2019.

- Bollig G. How do people interpret the term Last Aid? Bern, Switzerland: 10th World Research Congress of the EAPC, 2018.

- Zelko E, Bollig G. Report from the 2. International LAST AID Conference Online—The social impact of palliative care, October 30 2020, Maribor, Slovenia. Available online: https://www.aimspress.com/article/doi/10.3934/medsci.2021005

- Bollig G, Zelko E. Why should everybody learn Last Aid to provide end-of-life care? Arch Community Med Public Health 2020;6:198-9.

- Bollig G. Everybody should be able to care for seriously ill and dying people: -The Last Aid Course, telemedicine and compassionate communities can contribute to make home death possible for more people. Omsorg Nordisk Tidsskrift for Palliativ Medisin 2019;36:11-5.

- Meyer S, Bollig G. The Last Aid Course: Caring communities do need public knowledge about palliative care. Praxis Gemeindepädagogik 2020;73:8-10.