A review of the trials which examine early integration of outpatient and home palliative care for patients with serious illnesses

Introduction and definitions

The disease-centered, pathophysiological approach to medical care and the development of targeted innovations to various disease processes has brought about notable improvements in the technical aspects of managing disease. However, though the reductionist approach has brought about many advances, the sum of the advances is often less than the quality of care that is desired (1,2). The result is a dramatic increase in health care costs relative to outcomes. For example, in the United States rapidly rising health care costs have not lead to commensurate improvements in quality of health care compared to other economically developed countries (3). Technical advancements in care have not fully translated into benefits in quality of care at least in part due to the fact that the disease-centered approach often neglects the multi-dimensional aspects of patient and family quality of life, including physical and psychosocial-spiritual aspects of wellbeing. This gap is most apparent in the context of chronic and serious illnesses, where technological advancement and attendant costs are escalating rapidly; patient and family suffering is often multidimensional and significant; and care communication and decision-making is highly complex and enmeshed with values and goals.

Palliative care has emerged as an approach to care that specifically aims to address this gap inherent to the disease-centered approach in order to enhance care quality in the setting of serious illness, both for patients and their families and for health care systems. According to the World Health Organization’s definition, palliative care is an approach to care that aims to “improve the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual” (http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/). Palliative care is an approach to care that is applicable across the serious illness trajectory, from diagnosis to death, and hence aims to be practiced in concert with technical aspects of disease-focused care. However, despite this aim, palliative care is frequently involved in patient/family care late in the course of a serious illness (4-7). This late application of palliative care to patients with serious illness is thought to mitigate its potential benefits to patients, their families, and health care systems. Hence, efforts have been made by investigators to define the impact of earlier palliative care interventions within the context of serious illnesses, including patient, family and health care systems outcomes.

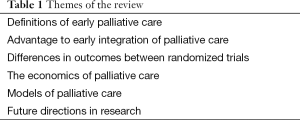

The purpose of this article is to review and discuss randomized control trials examining the integration of palliative care earlier in the course of the disease trajectory for patients with serious illnesses as an outpatient and at home. The themes that this review will cover are listed on Table 1. In the outpatient clinic and at home are more likely to be locations where patients with life-limiting illnesses are likely to be seen early in the course of their disease. In addition, this article will summarize systematic reviews of palliative care and its impact on quality of care outcomes. Finally, the review will, in addition to reviewing the outcomes of these trials, discuss their methodological differences, strengths, and weaknesses, and with this backdrop explore how these may contribute to heterogeneity of findings.

Full table

Methods

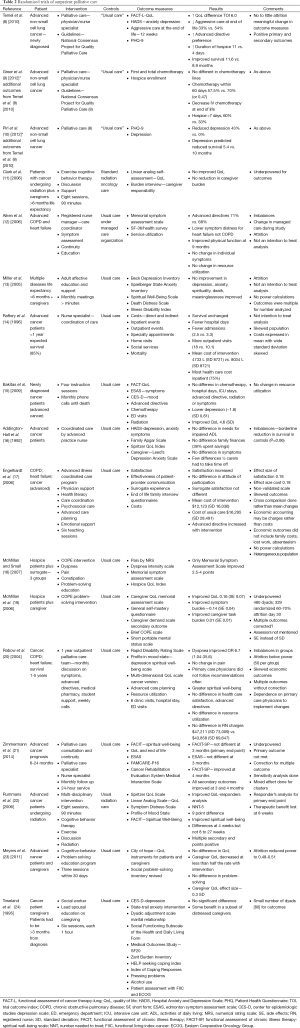

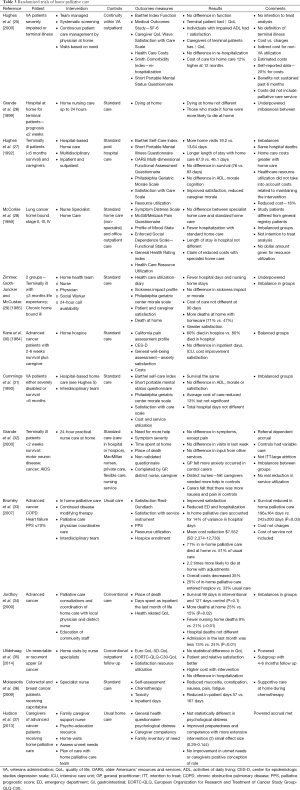

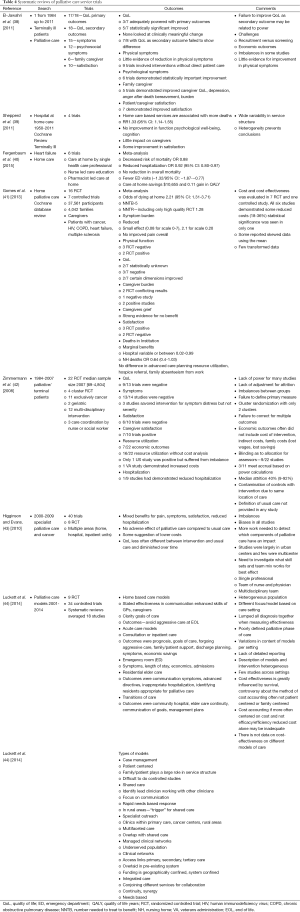

A systematic review of palliative care randomized control trials was performed. Various terms were used and the search was performed in PubMed. Search terms and yields were: “Therapy-Broad AND early palliative care cancer” (846 references), “systematic AND early palliative care cancer” (102 references), “early palliative care and quality of care” (702 references), “early palliative care and economics” (112 references), “early palliative care and outcomes” (325 references), “early palliative care and hospice” (187 references), “early palliative care and aggressive care” (166 references), “early palliative care and benefits” (120 references). From this search randomized trials were selected from 62 references derive from this search which appeared to be the primary studies. Hand searches were done on these references. Fifteen randomized control trials of outpatient palliative care and 13 randomized control trials of palliative home care were collected and collated into tables (Tables 2,3). Three of the manuscripts were reports from the same study but involved different outcomes and so reported separately on Table 2. In addition seven systematic reviews obtained and outcomes summarized (Table 4).

Full table

Full table

Full table

Results

The results of this systematic review are summarized on Tables 2-4. In this review of randomized controlled trials testing the intervention of early palliative care in various settings and populations, a multitude of advantages have been demonstrated. These advantages include improvement in certain symptoms such as depression, improved patient quality of life, reduced aggressive care at the end of life, increased advanced directives, reduced hospital length of stay and hospitalizations, improved caregiver burden and better maintenance of caregiver quality of life and reduction in the medical cost of care as well as patient and family satisfaction (Tables 2,3,4) (8-10,14,17,19,21,22,45,46). Yet there were randomized trials which demonstrate that symptoms are not improved, quality of life is not improved, and resource utilization and costs are not different from “usual” care (11-13,15,16,18,20,23,24). The same mixed findings are observed in randomized trials of palliative homecare services (Table 3) (25-37,41). Seven systematic reviews of randomized trials came to similar conclusions, with mixed findings in terms of palliative care benefits (Table 4) (38-44).

Why are there differences in the benefits to palliative care in randomized control trials?

There are notable methodological issues that may account for differences in findings among the randomized control trials of early palliative care. First, the structure of the interventions often consisted of a single professional and/or variably other professionals who were directly involved in patient care or in providing care continuity but not a full multidisciplinary palliative care team (11-13,16). Even if a multidisciplinary team regularly saw patients as an outpatient, recommendations were not be followed by those responsible for the direct care of patients diminishing the impact of the intervention (20). The palliative care consultative team was dependent on the primary physician to implement recommendations. Compliance to such recommendations were in fact be variable and influence outcomes. This may explain differences between two studies with the same intervention by design but with different outcomes (8,20).

Another methodological issue which occurred across all studies was the definition of “usual” or “standard” or “conventional” care. There were no descriptions of what was meant by “usual” care. Usual or conventional care is regionally-dependent and is provider-dependent. There was no mention of guidelines on “standard” practice. Negative findings may have been that usual care was not much different from the palliative intervention or in the opposite manner, suboptimal which would have diminished or magnified the interventions benefits respectively. In at least one study the “standard” of care changed in the middle of the study (12).

Furthermore, study designs and procedures were frequently flawed. Participants were referred or recruited rather than consecutively screened for eligibility. Referral based studies would potentially recruit a biased population, providing a convenient sample population which passed physician gatekeeping, but would not likely represent the population and thus limit generalizability (47). Imbalances between randomly-allocated groups were not infrequent (12,16,20,38). Blinding of the investigators assessing outcomes is reported in only a minority of studies (21). Power calculations for accrual based upon the primary outcome was performed in a minority of studies. Additionally, many studies were underpowered due to attrition and because outcomes were frequently multiple (11,13,19,21,23). This would increase the risk of a type II error. The median attrition rate reported in one systematic review was 40% (42). Other methodological concerns include issues related to the timing of assessment of outcomes. For example, improvements in the primary outcome in one trial were detected later than anticipated in the original design (21). In another trial the benefit to the primary outcome was transient (22). Other methodological issues include the fact that analyses frequently did not include all randomized participants, with most trials employing per protocol analyses (12-14). Only one study reported outcomes with a responder’s analyses with a significant improvement in the primary outcome measure in terms of numbers needed to treat (22,48). Sensitivity analyses was done in only a few studies. Few mentioned how missing data was handled. Some of the studies used words like “trends” for a non-significant outcomes or “near significant” findings which may have been a “spin” on the outcomes to place the study in a favorable light (49).

Definitions of “early” palliative care

Other issues likely influencing the variable findings of studies in early palliative care include the definition of “early” palliative care which has been variously constructed. In the study by Dr. Temel and colleagues, the definition of “early” palliative care for lung cancer was at the time of diagnosis of advanced cancer and nearly simultaneously with the initial oncologic consult; the initial location of consultation and continuity was provided in the outpatient setting (8). Others have defined “early” palliative care as being seen less than 3 months after diagnosis of advanced cancer (50) or as being seen by a palliative care specialist greater than 3 months before death (51). Another timeframe for “early” palliative care in the setting of advanced ovarian cancer was at the time of cis-platinum resistance (52). Additionally, the definition of “early” palliative care has been tied to the presence of certain prognostic signs and symptoms (53). “Early” palliative care has also been defined by where the palliative consultation takes place; outpatient versus inpatient (54). Another definition was based on the duration of continuity (greater than 90 days, 31-90 days, 11-30 days and 1-10 days) before death (55). Hence, there is no universally accepted definition of “early” palliative care which complicates assessment of early palliative care benefits. Based upon randomized trials, it does appear that for full benefits of palliative care to be realized, continuity by a multidisciplinary team is needed for at least 3-4 months (8,21,45).

Definitions of patients eligible for palliative care

There is also variation in the definition of palliative care when reviewing home palliative care services. Patients with heart failure or chronic obstructive lung disease were considered for homecare if admitted to the hospital twice or intensive care stay once (56,57). Admission to palliative homecare was based on various periods of time; survival expectation of less than 24 months, expected survival of 12 months, expected survival of less than 6 months or less or even imminently close to death (2 weeks) (12,31-33,58,59). Alternatively, impairment of activities of daily living or been homebound status with heart failure, chronic obstructive lung disease or a terminal illness were criteria for initiation of palliative homecare (25). As a result, optimal timing for initiating palliative homecare cannot be determined on the bas based on randomized control trials.

Another likely contributor to the heterogeneity of findings across studies of early palliative care is the heterogeneity of palliative care models that have been used in the randomized control trials. Each location of care may have a different important outcome (inpatient care, inpatient consultative services, outpatient integrated care and home care) (44). There is little evidence to guide interventionists in their choice of the most effective model of care.

Models of palliative care

Population heterogeneity in many the trials may have confounded outcomes. The assumption that the same model of care was equally effective across different diseases is unsubstantiated. In addition there is a poor definition of the “palliative” phase of illness. Certain models of care may work better at different phases of illness, early versus late cancer for instance or in different diseases or disease trajectories. The hospice case management model is used at the end of life and shared care or integrated care or consultative models are frequently adopted in palliative care. Models of care may also depend on cultural and ethnic background, family dynamics and patient location. Referring specialists may have a preference for engagement and timing of referral which will influence care models. There are few comparative trials of palliative care models with reasonable quality. There is some evidence that in-patient palliative care provided better pain control than home care of conventional hospital care, but this research is limited and open to criticism (60). Research on palliative home care teams and coordinating nurses has demonstrated limited impact on quality of life over conventional care for patients dying at home. These negative findings are due in part to the limitations in the assessment tools (60). There is a need for other larger studies to provide clear evidence as to whether specialist palliative care services provide improvements in patients’ quality of life. Few studies cross service lines (inpatient to outpatient to home care) which patients frequently do with life limiting illnesses. Models of care within randomized studies frequently were described vaguely and in less than optimal detail (44). And at the present time there is no data on the cost-effectiveness of different models of palliative care (44).

The price of palliative care: is there a benefit?

The gold standard for cost-benefit research involves changes in healthcare resources (personnel, materials, equipment and facilities) where expenditures are offset by reductions in spending for other medical services (61). The published data of cost benefit analysis in randomized trials of palliative care have focused exclusively on patient medical costs with mixed results. The variability within groups is wide; the standard deviation is larger than the mean (wide coefficient of variation) indicating lack of precision and skewed economic data; it is likely that outliers played a role in determining economic outcomes since all studies used the mean as a comparison (14,17,20). Cost-of-illness estimations were used in a heterogeneous population of terminally ill patients which included cancer, heart failure and chronic obstructive lung disease (17). However, the cost-of-illness studies should use event-costs from populations with similar diseases (62). Many studies have suggested that palliative care reduces hospitalizations and aggressive interventions at the end of life. However, these studies did not directly measure cost and rather assumed an economic benefit associated with reduced aggressive care at the end of life (8). Some have demonstrated that palliative interventions and advanced directives do not reduce medical costs (16,20,30). Many of the studies did not include the cost of the intervention in their analyses of benefit or it is not mentioned in the manuscript (17,20). One study demonstrated higher costs with the intervention (35). Current studies fall short of the goal of measuring all relevant factors to assessing costs-benefits and instead have focused narrowly on patient medical costs. A classification of palliative care costs-benefits involves four categories: (I) patient medical factors which involve improved quality and quantity of life cost of medical care services; (II) patient nonmedical factors include changes in workplace productivity and accommodation by employers; (III) family medical factors which include changes in quality of life of family members and changes in healthcare use by family members; (IV) family nonmedical factors which include changes in workplace productivity and school performance of family members (61).

Typical methods for estimating costs involve examination of gross charges and applying a “cost to charge” ratio to estimate costs. However, in health care reimbursement charges often bear little relationship to costs. Hospital charges may exceed costs by a factor of two or more. In the same manner, actual reimbursements are at best a good approximation of costs (61). Several studies have shown that palliative care improves the quality of life of patients. This has not been integrated into cost benefit studies as a quality adjusted life year analysis. The commonly used instruments in palliative care which measure quality of life have their roots in psychometrics; they are not designed for health care utility but rather as a measure of human characteristics. There is a need to construct new quality of life scales in palliative care to be consistent with economic theory if it is to be used in a cost-effective analysis. Providing end of life care is unique enough in achieving “a good death” that a condition specific measure for cost-effectiveness in needed. Providing a good death, for example, may reduce health problems of the surviving spouse and hence have an economic benefits which is indirect (61).

The National Institute of Health has reported that costs associated with workplace productivity loss can exceed the direct costs of medical care for many chronic illnesses (61). In the study reported by Dr. Addington-Hall and colleagues, 38% of family spent their life savings on end of life care for their loved ones in part related to loss of income and increased medical expenditures needed at the end of life for their loved one (16). A recent study found that the cost of caregiving was significant leading in some instances to family debt or bankruptcy. Direct costs to families include transportation, food and medication; indirect costs were loss of employment or absenteeism (family medical leave), cultural and caregiver stress, burden and impaired health. The palliative care context in this study increased costs, as the goals of meeting patient needs were prioritized over the cost of care. In a similar manner reducing the length of stay in the hospital may in fact increase family and caregiver costs (63). Research is desperately needed to quantify the financial contribution of families to palliative care and the effect of palliative care on the financial health of the family. It is important as palliative care becomes integrated early into the care of serious illnesses that a uniform model of care be developed for each stage of disease and that the model be adapted to the trajectory of disease.

Future direction in research

Complex interventions are intrinsic to multidisciplinary palliative care services and palliative care as integral with other services to the care advanced illnesses. Complex interventions involved multiple interacting components each of which contribute to the outcome. Careful modeling of complex interventions is essential in healthcare services research. Such research requires formal feasibility studies of each component and a mixed method design which includes qualitative research techniques (64-66). Qualitative outcomes are used to confirm quantitative findings and to place quantitative findings in context within a study. Qualitative techniques can be used to determine why one component of an intervention works and another does not work. Unfortunately qualitative research methods are rarely incorporated into randomized trials. It would be important in future palliative care service research trials to incorporate qualitative methods to fully assess quantitative outcomes.

Most randomized trials of palliative care services have been parallel in design. However, other methods of testing palliative care services could involve stepped wedge designed trials where the intervention is rolled out over time to a larger number of individuals. Comparisons are made between those receiving the intervention and those who are still receiving standard care (67). The other alternative is fast-track randomization where a group of individuals are randomized to receive the intervention and a group who well in the future cross over to the intervention. The benefits of the intervention are measured at the time of crossover. The crossover has to be delayed long enough to allow the intervention benefits to be fully realized but short enough to minimize attrition (68-70). Both methods allow all participants to receive the benefits of palliative care but would also adequately test the benefits of early palliative care.

Conclusions

Recent randomized trials of palliative care as an integrated intervention early in that trajectory of a life limiting illness has variably demonstrated benefits to patient and caregiver wellbeing and to health care utilization. These findings point to the benefits of involving multidisciplinary palliative care teams early in the course of serious illness. However, notable limitations to these studies highlight the need for further evidence. We need an evidence-based definition of “early” palliative care to determine the optimal timing to intervene. Furthermore, studies are needed to determine what models of care are effective and to define the best models of care for variable populations (e.g., inpatient vs. home care) and disease types. Finally, the economic impact of palliative care should be assessed in a manner that includes all medical (including the cost of the palliative care intervention) and non-medical factors contributing to costs. With a rigorous evidence-base guiding its development and implementation, effective models of palliative care can be delivered at appropriate time points in the course of illness, to the betterment of patients, families, and health care systems.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Kessler R, Glasgow RE. A proposal to speed translation of healthcare research into practice: dramatic change is needed. Am J Prev Med 2011;40:637-44. [PubMed]

- Taplin SH, Anhang Price R, Edwards HM, et al. Introduction: Understanding and influencing multilevel factors across the cancer care continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2012;2012:2-10.

- Burke LA, Ryan AM. The complex relationship between cost and quality in US health care. Virtual Mentor 2014;16:124-30. [PubMed]

- Fukui S, Fujita J, Tsujimura M, et al. Late referrals to home palliative care service affecting death at home in advanced cancer patients in Japan: a nationwide survey. Ann Oncol 2011;22:2113-20. [PubMed]

- Baek YJ, Shin DW, Choi JY, et al. Late referral to palliative care services in Korea. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:692-9. [PubMed]

- Ferrell BR. Late referrals to palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2588-9. [PubMed]

- Morita T, Akechi T, Ikenaga M, et al. Late referrals to specialized palliative care service in Japan. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2637-44. [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733-42. [PubMed]

- Greer JA, Pirl WF, Jackson VA, et al. Effect of early palliative care on chemotherapy use and end-of-life care in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:394-400. [PubMed]

- Pirl WF, Greer JA, Traeger L, et al. Depression and survival in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: effects of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1310-5. [PubMed]

- Clark MM, Rummans TA, Sloan JA, et al. Quality of life of caregivers of patients with advanced-stage cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2006;23:185-91. [PubMed]

- Aiken LS, Butner J, Lockhart CA, et al. Outcome evaluation of a randomized trial of the PhoenixCare intervention: program of case management and coordinated care for the seriously chronically ill. J Palliat Med 2006;9:111-26. [PubMed]

- Miller DK, Chibnall JT, Videen SD, et al. Supportive-affective group experience for persons with life-threatening illness: reducing spiritual, psychological, and death-related distress in dying patients. J Palliat Med 2005;8:333-43. [PubMed]

- Raftery JP, Addington-Hall JM, MacDonald LD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the cost-effectiveness of a district co-ordinating service for terminally ill cancer patients. Palliat Med 1996;10:151-61. [PubMed]

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741-9. [PubMed]

- Addington-Hall JM, MacDonald LD, Anderson HR, et al. Randomised controlled trial of effects of coordinating care for terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ 1992;305:1317-22. [PubMed]

- Engelhardt JB, McClive-Reed KP, Toseland RW, et al. Effects of a program for coordinated care of advanced illness on patients, surrogates, and healthcare costs: a randomized trial. Am J Manag Care 2006;12:93-100. [PubMed]

- McMillan SC, Small BJ. Using the COPE intervention for family caregivers to improve symptoms of hospice homecare patients: a clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum 2007;34:313-21. [PubMed]

- McMillan SC, Small BJ, Weitzner M, et al. Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer 2006;106:214-22. [PubMed]

- Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, et al. The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:83-91. [PubMed]

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721-30. [PubMed]

- Rummans TA, Clark MM, Sloan JA, et al. Impacting quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:635-42. [PubMed]

- Meyers FJ, Carducci M, Loscalzo MJ, et al. Effects of a problem-solving intervention (COPE) on quality of life for patients with advanced cancer on clinical trials and their caregivers: simultaneous care educational intervention (SCEI): linking palliation and clinical trials. J Palliat Med 2011;14:465-73. [PubMed]

- Toseland RW, Blanchard CG, McCallion P. A problem solving intervention for caregivers of cancer patients. Soc Sci Med 1995;40:517-28. [PubMed]

- Hughes SL, Weaver FM, Giobbie-Hurder A, et al. Effectiveness of team-managed home-based primary care: a randomized multicenter trial. JAMA 2000;284:2877-85. [PubMed]

- Grande GE, Todd CJ, Barclay SI, et al. Does hospital at home for palliative care facilitate death at home? Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 1999;319:1472-5. [PubMed]

- Hughes SL, Cummings J, Weaver F, et al. A randomized trial of the cost effectiveness of VA hospital-based home care for the terminally ill. Health Serv Res 1992;26:801-17. [PubMed]

- McCorkle R, Benoliel JQ, Donaldson G, et al. A randomized clinical trial of home nursing care for lung cancer patients. Cancer 1989;64:1375-82. [PubMed]

- Zimmer JG, Groth-Juncker A, McCusker J. A randomized controlled study of a home health care team. Am J Public Health 1985;75:134-41. [PubMed]

- Kane RL, Wales J, Bernstein L, et al. A randomised controlled trial of hospice care. Lancet 1984;1:890-4. [PubMed]

- Cummings JE, Hughes SL, Weaver FM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of Veterans Administration hospital-based home care. A randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med 1990;150:1274-80. [PubMed]

- Grande GE, Todd CJ, Barclay SI, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a hospital at home service for the terminally ill. Palliat Med 2000;14:375-85. [PubMed]

- Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:993-1000. [PubMed]

- Jordhøy MS, Fayers P, Saltnes T, et al. A palliative-care intervention and death at home: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2000;356:888-93. [PubMed]

- Uitdehaag MJ, van Putten PG, van Eijck CH, et al. Nurse-led follow-up at home vs. conventional medical outpatient clinic follow-up in patients with incurable upper gastrointestinal cancer: a randomized study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:518-30. [PubMed]

- Molassiotis A, Brearley S, Saunders M, et al. Effectiveness of a home care nursing program in the symptom management of patients with colorectal and breast cancer receiving oral chemotherapy: a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:6191-8. [PubMed]

- Hudson P, Trauer T, Kelly B, et al. Reducing the psychological distress of family caregivers of home-based palliative care patients: short-term effects from a randomised controlled trial. Psychooncology 2013;22:1987-93. [PubMed]

- El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Temel JS. Does palliative care improve outcomes for patients with incurable illness? A review of the evidence. J Support Oncol 2011;9:87-94. [PubMed]

- Shepperd S, Wee B, Straus SE. Hospital at home: home-based end of life care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;CD009231. [PubMed]

- Fergenbaum J, Bermingham S, Krahn M, et al. Care in the Home for the Management of Chronic Heart Failure: Systematic Review and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2015;30:S44-51. [PubMed]

- Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;6:CD007760. [PubMed]

- Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: a systematic review. JAMA 2008;299:1698-709. [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, Evans CJ. What is the evidence that palliative care teams improve outcomes for cancer patients and their families? Cancer J 2010;16:423-35. [PubMed]

- Luckett T, Phillips J, Agar M, et al. Elements of effective palliative care models: a rapid review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:136. [PubMed]

- Dahlin CM, Kelley JM, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for lung cancer: improving quality of life and increasing survival. Int J Palliat Nurs 2010;16:420-3. [PubMed]

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for rural patients with advanced cancer: baseline findings, methodological challenges, and solutions. Palliat Support Care 2009;7:75-86. [PubMed]

- Godager G, Iversen T, Ma CT. Competition, gatekeeping, and health care access. J Health Econ 2015;39:159-70. [PubMed]

- Yost KJ, Eton DT. Combining distribution- and anchor-based approaches to determine minimally important differences: the FACIT experience. Eval Health Prof 2005;28:172-91. [PubMed]

- Boutron I, Altman DG, Hopewell S, et al. Impact of spin in the abstracts of articles reporting results of randomized controlled trials in the field of cancer: the SPIIN randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:4120-6. [PubMed]

- Vergnenègre A, Hominal S, Tchalla AE, et al. Assessment of palliative care for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in France: a prospective observational multicenter study (GFPC 0804 study). Lung Cancer 2013;82:353-7. [PubMed]

- Amano K, Morita T, Tatara R, et al. Association between early palliative care referrals, inpatient hospice utilization, and aggressiveness of care at the end of life. J Palliat Med 2015;18:270-3. [PubMed]

- Lowery WJ, Lowery AW, Barnett JC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of early palliative care intervention in recurrent platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2013;130:426-30. [PubMed]

- Thoonsen B, Groot M, Engels Y, et al. Early identification of and proactive palliative care for patients in general practice, incentive and methods of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract 2011;12:123. [PubMed]

- Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer 2014;120:1743-9. [PubMed]

- Lee YJ, Yang JH, Lee JW, et al. Association between the duration of palliative care service and survival in terminal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:1057-62. [PubMed]

- Penrod JD, Deb P, Luhrs C, et al. Cost and utilization outcomes of patients receiving hospital-based palliative care consultation. J Palliat Med 2006;9:855-60. [PubMed]

- Penrod JD, Deb P, Dellenbaugh C, et al. Hospital-based palliative care consultation: effects on hospital cost. J Palliat Med 2010;13:973-9. [PubMed]

- Brumley RD, Enguidanos S, Cherin DA. Effectiveness of a home-based palliative care program for end-of-life. J Palliat Med 2003;6:715-24. [PubMed]

- Walczak A, Butow PN, Clayton JM, et al. Discussing prognosis and end-of-life care in the final year of life: a randomised controlled trial of a nurse-led communication support programme for patients and caregivers. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005745. [PubMed]

- Salisbury C, Bosanquet N, Wilkinson EK, et al. The impact of different models of specialist palliative care on patients' quality of life: a systematic literature review. Palliat Med 1999;13:3-17. [PubMed]

- Boni-Saenz AA, Dranove D, Emanuel LL, et al. The price of palliative care: toward a complete accounting of costs and benefits. Clin Geriatr Med 2005;21:147-63. [PubMed]

- Goeree R, O'Reilly D, Hopkins R, et al. General population versus disease-specific event rate and cost estimates: potential bias for economic appraisals. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2010;10:379-84. [PubMed]

- Gott M, Allen R, Moeke-Maxwell T, et al. 'No matter what the cost': A qualitative study of the financial costs faced by family and whānau caregivers within a palliative care context. Palliat Med 2015;29:518-28. [PubMed]

- Davis MP, Mitchell GK. Topics in research: structuring studies in palliative care. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2012;6:483-9. [PubMed]

- Hagen NA, Biondo PD, Brasher PM, et al. Formal feasibility studies in palliative care: why they are important and how to conduct them. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;42:278-89. [PubMed]

- Audrey S. Qualitative research in evidence-based medicine: improving decision-making and participation in randomized controlled trials of cancer treatments. Palliat Med 2011;25:758-65. [PubMed]

- Brown CA, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge trial design: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol 2006;6:54. [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, Booth S. The randomized fast-track trial in palliative care: role, utility and ethics in the evaluation of interventions in palliative care? Palliat Med 2011;25:741-7. [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, Costantini M, Silber E, et al. Evaluation of a new model of short-term palliative care for people severely affected with multiple sclerosis: a randomised fast-track trial to test timing of referral and how long the effect is maintained. Postgrad Med J 2011;87:769-75. [PubMed]

- Farquhar MC, Prevost AT, McCrone P, et al. Study protocol: Phase III single-blinded fast-track pragmatic randomised controlled trial of a complex intervention for breathlessness in advanced disease. Trials 2011;12:130. [PubMed]