Models of integration of oncology and palliative care

IntroductionOther Section

Palliative care is an interprofessional discipline that “improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual” (1). Over the past few years, there have been a growing number of studies supporting the integration of palliative care into oncology practice. Specifically, the addition of specialist palliative care to routine oncology care, as compared to oncologic care alone, was associated with improved quality of life, quality of end-of-life care, decreased rates of depression, illness understanding, and patient satisfaction (2-5). Thus, the question is no longer whether it is a good idea to integrate palliative care and oncology, but rather how this integration should occur to optimize various health outcomes (6,7). Some key questions raised include:

- Who should receive a palliative care referral?

- When should palliative care be introduced?

- How much primary palliative care should oncologists and primary care physicians be prepared to provide?

- What setting is most appropriate for palliative care delivery?

Integration in healthcare is a complex and abstract concept. The extent of integration can be classified into three levels (8):

- Linkage—oncologists make palliative care referral;

- Coordination—defined processes of interaction between oncology and palliative care. For example, institution of clinical care pathways for palliative care referral based on pre-defined automatic triggers;

- Full integration—pooled resources between oncology and palliative care.

Importantly, the ideal level of integration may vary significantly based on the healthcare system’s size and resources, patient population and needs, and the extent of palliative care already provided by oncologists and primary care physicians.

The goal of this review is to examine contemporary conceptual and clinical models of integration of oncology and palliative care. Conceptual models are useful to help stakeholders (i.e., policy makers, administrators, clinicians, patients and researchers) better understand the rationale for integration, to compare the risks and benefits among different practices, and to define a vision towards integration. Clinical models provide actual data on the feasibility, efficacy and effectiveness of integration in a specific setting, and can inform the challenges and opportunities for integration. Although educational, research and administrative models are also important; they are beyond the scope of this review. Here, the term “supportive care” is defined as “the provision of the necessary services for those living with or affected by cancer to meet their informational, emotional, spiritual, social or physical needs during their diagnostic, treatment, or follow-up phases encompassing issues of health promotion and prevention, survivorship, palliation and bereavement” (9,10). Thus, palliative care is essentially supportive care for patients with advanced disease (11).

Conceptual modelsOther Section

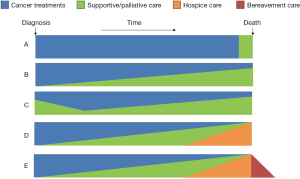

Time-based model

This model is commonly used in the literature to describe integration. It highlights the timing and extent of palliative care involvement along the disease trajectory (7,12,13). Currently, palliative care referral often occurs in the last weeks or months of life (Figure 1A) (14). This creates a “self-fulfilling prophecy”, resulting in the stigma that palliative care is associated with death and dying. In the integration model, palliative care is introduced to cancer patients from time of diagnosis of advanced disease, with an increased level of involvement over time as their supportive care needs increase (Figure 1B). A few variations on this model exist. Some models illustrate the amount of palliative care vary widely over time (Figure 1C), some include hospice care at the end-of-life (Figure 1D), and some include bereavement on the right hand side of the diagram (Figure 1E). This model is appealing because it highlights the timing of integration.

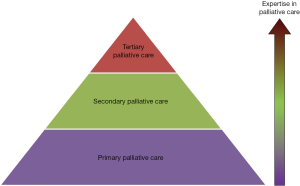

Provider-based model

This palli-centric model focuses on the provision of palliative care according to the level of patient complexity and the setting (Figure 2) (15-17). Primary palliative care is provided by oncologists and primary care providers. These teams see patients in the front lines, and need to provide a high basal level of supportive care. The level of palliative care training for these providers remains to be defined. Patients with more complex care needs will be referred to secondary palliative care, in which specialist palliative care teams see patients as consultants in the inpatient or outpatient settings. In tertiary palliative care, the palliative care team functions as the attending service, providing care for patients with the most complex supportive care needs, such as in an acute palliative care unit. Tertiary palliative care teams are often located in academic centers. In addition to clinical care, they are also often active in education and research.

In an alternate model, some have proposed that primary, secondary and tertiary palliative care correspond to the supportive care provided by primary care teams, oncology teams and specialist palliative care teams, respectively (18).

The provider-based model raises important questions regarding how much primary palliative care should be provided by oncologists and primary care providers, and also how available should secondary and tertiary palliative care teams be.

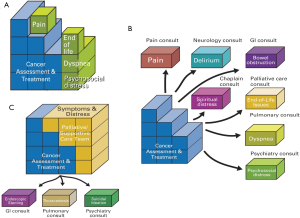

Issue-based model

This onco-centric model focuses on the many oncologic and supportive care issues that oncologists face on a daily basis (19). In the solo practice model, the oncologist is responsible for cancer diagnosis, staging and treatment, as well as all the supportive care issues such as pain, fatigue, nausea, depression, and spiritual distress (Figure 3A). While the oncologist often provides a reasonable level of supportive care in the front line setting, he or she may not be able to address all the concerns comprehensively if the patient care needs are complex. This is partly because of the lack of time, the lack of an interprofessional team to address the multi-dimensional aspects of care, the lack of routine symptom screening resulting in under-diagnosis and under-treatment of various symptoms, and the lack of formal palliative care training. This approach is reasonable, particularly in settings in which access to specialist palliative care teams is limited. Under this model, it would be important to maximize the delivery of primary palliative care by providing the oncologist with adequate supportive care education and resources.

In the congress model, instead of providing supportive care herself, the oncologist refers her patients to various specialists each addressing a different supportive care concerns (Figure 3B). For instance, a patient with pain, fatigue, depression and spiritual concerns will have a referral to cancer pain clinic, fatigue clinic, psychiatry and chaplaincy. Although this approach allows patients to have expert input, it is potentially confusing to patients, may result in conflicting recommendations, and is often prohibitively expensive to the patients and the healthcare system. Thus, the congress model is generally not recommended.

In the integrated care model, oncologists routinely refer patients to specialist palliative care teams early in the disease trajectory (Figure 3C). Under this model, the oncologist may provide as much or as little supportive care as she desires, knowing that her patients will always be able to receive high quality palliative care. The integrated care model is recommended because it standardizes patients’ access to timely and comprehensive palliative care concurrent with oncologic care, normalizes the introduction of palliative care, minimizes the demand for oncologists to provide both high quality oncologic and supportive care compared to the solo model, and reduces the need to refer to other supportive care disciplines compared to the congress model.

The strength of the issue-based model is that it clearly outlines the cancer care package from the oncologic standpoint, and explains the benefits of involving palliative care concurrent with oncologic care.

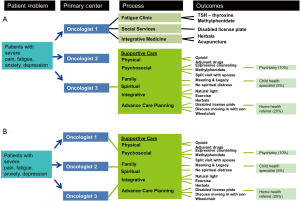

System-based model

This conceptual patient-centric model depicts how a typical patient navigates the healthcare system to access supportive care (20). In the contemporary model, the timing and eligibility for a palliative care referral is not standardized in most institutions, and is dependent on the preferences of individual oncologists (Figure 4A). Thus, the same patient, depending on which oncologist she sees, may receive no specialist supportive care referral (as in the solo model), fragmented referral to multiple disciplines (as in the congress approach), or a palliative care referral (as in the integrated care model).

In the integrated system-based model, a patient who meets the pre-defined criteria would be referred to palliative care, regardless of which oncologist she sees (Figure 4B). This would streamline the referral process, and ensure patients receive high level of supportive care under an integrated model. A number of groups have proposed criteria for initiating a palliative care referral, including the National Comprehensive Cancer Network palliative care guidelines (21), and a group in Germany that proposed several disease-based criteria for referral (22,23).

This system-based model complements the issue-based model, and highlights the comprehensive supportive care assessments and treatments provided by the palliative care team. It further illustrates why a clinical care pathway standardizing referral to specialist palliative care could improve access to palliative care.

Clinical modelsOther Section

The conceptual models above outline a vision for the interactions necessary between oncologists and palliative care teams toward integration, particularly in regard to referral timing and team roles. Clinical models apply the principles in the conceptual models to different clinical environments. They highlight the strategies to foster communication and collaboration in actual practice, illustrate the logistical challenges, and provide data regarding clinical outcomes of integration. A recent systematic review identified 4 clinical structure, 13 clinical process, 8 educational, 4 research and 9 administrative aspects of integration (Table 1) (24). In this section, we will review the evidence on two different clinical models of integration—outpatient palliative care clinics and embedded models.

Integration models involving outpatient palliative care clinics

Palliative care has evolved over the past few decades from the delivery of predominantly community-based hospice care for patients at the end-of-life, to hospital-based inpatient consultations for acutely ill patients, and now to ambulatory clinic-based services for patients earlier in the disease trajectory. Because oncology is an ambulatory discipline, outpatient palliative care clinics promote integration by allowing patients to be seen earlier in the disease trajectory, thus facilitating preventative symptom control, longitudinal psychosocial care, and more opportunities for end-of-life discussions. Palliative care clinics first became available in Canada and Germany in the 1990s (25). They have received more attention nowadays because of the effort to introduce palliative care early in the disease trajectory.

Few groups have published their experience with palliative care outpatient clinics in the everyday clinical setting (20,26-29). As an example, the outpatient palliative care clinic at MD Anderson Cancer Center operates 5 days a week from 8 am to 5 pm. It consists of four physicians, eight clinic nurses, two social workers and two psychologists. A dietician, a chaplain, and a child-life specialist are also available if needed. The number of patients and staff have grown significantly over the past 5 years (30).

The successful growth was likely secondary to several factors, including evidence to support improved symptom control with palliative care (31) and increasing awareness of the role of palliative care among oncology professionals. In randomized controlled trials, early palliative care delivered predominantly through outpatient clinics was associated with improved quality of life, better mood, and improved patient satisfaction compared to usual oncologic care (3,5,32). In a cohort study examining the impact of setting and timing of referral on quality of end-of-life outcomes, Hui et al. also found that patients who had a palliative care consultation in the outpatient setting had significantly lower rates of hospitalization, emergency room visits, intensive care unit admissions in the last 30 days of life compared to those who were first seen by palliative care as inpatients (33).

Another potential reason for the growth in outpatient clinics is the rebranding effort to overcome the stigma associated with “palliative care”. In a survey that examined oncologists and midlevel providers’ perception of the term “palliative care”, 57% felt that it was synonymous with hospice and end-of-life, 44% reported it could decrease hope in patient and families, and 23% believed it was a barrier for referral. In contrast, the term “Supportive Care” was much better received (15%, 11%, and 7% agreement, respectively, P<0.001 for all comparisons) (34). Based on these findings, our outpatient clinic changed its name to “Supportive Care Center” in 2007. Compared to the before name change period, the after name change period had a higher number of referrals (41% increase) and also earlier referrals among outpatients (median 6.2 vs. 4.7 months, P<0.001) (35). This was supported by a Canadian survey in which one-third of oncologists responded that they would likely refer patients earlier if the service was renamed supportive care (36). More recently, Maciasz et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial to examine patient’s perception of “Palliative care” vs. “Supportive care”, and reported that “Supportive Care” was associated with a better understanding (7.7 vs. 6.8, P=0.021), more favorable impressions (8.4 vs. 7.3, P=0.002) and higher future perceived need (8.6 vs. 7.7, P=0.017) (37).

Despite the growing appreciation for palliative care clinics, only 59% of National Cancer Institute (NCI) designed cancer centers and 22% of non-NCI cancer centers reported having outpatient palliative care clinics according to a national survey in 2010 (14). This suggests that there is significant room for improvement in regard to the infrastructure of outpatient palliative care. Encouragingly, a more recent international survey suggests that a growing proportion of centers had palliative care clinics (38).

A recent qualitative study examined the various components of palliative care in the Temel study, and identified seven key elements: relationship and rapport building, addressing symptoms, addressing coping, establishing illness understanding, discussing cancer treatments, end-of-life planning, and engaging family members (39). Further research is needed to standardize the clinic structure, operation, and criteria/timing of referral.

Instead of an interdisciplinary team, some have examined the effect of nurse-led palliative care interventions. In Project ENABLE II study, Bakitas et al. randomized 322 patients within 8 weeks of diagnosis of advanced cancer to either an advanced practice nurse-led palliative care phone based intervention or usual care (40). The intervention arm included four structured educational and problem solving sessions followed by at least monthly telephone sessions, and was associated with a statistically significant improvement in quality of life as measured by FACIT-Pal (P=0.02) and mood (P=0.02) compared to control. However, symptom control and quality of end-of-life care did not differ significantly. The negative findings may be explained by the fact that this intervention was predominantly led by a single discipline. It may be difficult to effectively address symptom control and end-of-life decision making without a comprehensive team. Furthermore, two smaller studies examining nurse-led interventions had mixed results (41,42). Thus, the evidence to support these uni-disciplinary interventions remains limited at this time.

Embedded integration models

An alternative to the outpatient model is to have the palliative care team members embedded in the oncology office. The major advantages of the embedded model is that this creates more opportunities for oncologists and palliative care teams to communicate, collaborate and coordinate supportive care, to discuss patient cases, and to provide patients with rapid access to specialist palliative care. However, there is a paucity of literature on embedded models currently.

In a retrospective analysis, Muir et al. compared three service models of delivering palliative care in a community oncology setting: (I) palliative care embedded in oncology; (II) palliative care education alone; (III) no specific palliative care intervention (43). In the embedded model, a palliative care physician and fellow were available for a half day per week. This model was associated with a greater increase in referral, and saved oncologists an average of 170 min per referral.

Dyar et al. conducted a clinical trial of 26 patients with metastatic cancer randomizing them to either an advanced practice nurse working under the supervision of an oncologist to provide supportive care or usual care without the advanced practice nurse (42). The primary endpoint, time to hospice referral was not reported due to premature study closure. No difference was found in secondary outcomes such as the FACT-G physical subscale, functional subscale, social/family subscale and the total score; however, the advanced practice nurse arm was associated with improved FACT-G emotional well-being (1.2 vs. −4.5) and overall mental state (19 vs. −10, P=0.02).

In another study that utilized a quasi-experimental design, Prince-Paul et al. embedded a palliative care advanced practice nurse in a community oncology center (41). The authors reported that palliative care was associated with a reduction of hospitalization (odds ratio 0.16, P<0.01) and a lower mortality rate at 4 months (odds ratio 24.6, P=0.02). However, other outcomes such as symptoms and quality of life did not differ significantly.

Embedded models are not always met with success. A single arm feasibility study enrolled patients within 8 weeks of diagnosis of advanced lung cancer to receive concurrent palliative care delivered by a palliative medicine consultant who attended the oncology clinic (44). Three of 13 eligible patients were enrolled over a 5-month period. The investigators reported that they had difficulty finding patients who were willing to undertake an additional appointment.

Although embedded clinics offer some potential benefits, there are several challenges. First, it may be logistical difficult to find clinic space for the entire palliative care team, which may explain why all of the above studies have only one discipline involved (i.e., physician or nurse). Second, even if same day palliative care consultations were possible with this setup, patients may not be able to take advantage of this because of lack of time or energy. Third, the optimal nature of interaction among the oncology team, palliative care team and patients remains to be defined. Finally, it is unclear if embedded clinics are superior to stand alone palliative care clinics in regard to the frequency and timing of referrals, patient outcomes and clinician outcomes. Further research is thus required.

Summary

Palliative care is rapidly gaining acceptance in mainstream oncology, with a growing body of evidence to support its integration into oncology practice. The goal of integration is to optimize patient access to supportive care, and ultimately, to improve the quality of life of patients and caregivers. As summarized in this review, there are multiple conceptual models and innovative approaches to promote integration. Based on the conceptual and clinical models, several common themes have emerged on how we can better integrate oncology and palliative care. At the same time, for every question answered, there are many more questions raised:

- Who should receive a palliative care referral? Palliative care is appropriate for patients with advanced incurable disease, and not only those in the last weeks/months of life; however, there is currently no consensus on the criteria for specialist palliative care. Furthermore, whether specialist palliative care should be introduced for patients with curable disease remains a topic of debate;

- When should palliative care be introduced? Palliative care is best introduced early in the disease trajectory; however, the optimal timing remains to be determined;

- How much primary palliative care should oncologists and primary care physicians providinge? A vast majority of oncologists agree that they should be actively providing primary palliative care; however, the extent of palliative care education and the amount of supportive care services they provide vary widely;

- What setting is most appropriate for palliative care delivery? Outpatient palliative care clinics are good models to support integration. However, the structure and process of these clinics remains to be defined and standardized.

Given the tremendous heterogeneity in healthcare systems, patient population, resource availability, clinician training, and attitudes and beliefs toward palliative care worldwide, it is important to emphasize that no one model will offer the solution for all. For example, Germany has recently developed a National Palliative Care Consensus Guideline addressing some of the above questions based on existing evidence, which will be released in mid-2015. Much research is necessary to determine which aspect of integration can help improve clinical outcomes. Individual institutions will need to define the optimal level of integration that would have the greatest acceptance and impact at the local level, monitor the clinical outcomes, and publish their findings so others can learn from their experience.

AcknowledgementsOther Section

None.

FootnoteOther Section

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ReferencesOther Section

- WHO Definition of Palliative Care, World Health Organization, 2002. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial to improve palliative care for rural patients with advanced cancer: baseline findings, methodological challenges, and solutions. Palliat Support Care 2009;7:75-86. [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733-42. [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2319-26. [PubMed]

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721-30. [PubMed]

- Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:880-7. [PubMed]

- Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: accomplishments, the need, next steps -- from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3052-8. [PubMed]

- Leutz WN. Five laws for integrating medical and social services: lessons from the United States and the United Kingdom. Milbank Q 1999;77:77-110. [PubMed]

- Hui D, De La Cruz M, Mori M, et al. Concepts and definitions for “supportive care,” “best supportive care,” “palliative care,” and “hospice care” in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:659-85. [PubMed]

- Page B. What is supportive care? Can Oncol Nurs J 1994;4:62-3.

- Hui D. Definition of supportive care: does the semantic matter? Curr Opin Oncol 2014;26:372-9. [PubMed]

- Von Roenn JH, Voltz R, Serrie A. Barriers and approaches to the successful integration of palliative care and oncology practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2013;11 Suppl 1:S11-6. [PubMed]

- Rocque GB, Cleary JF. Palliative care reduces morbidity and mortality in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013;10:80-9. [PubMed]

- Hui D, Elsayem A, De la Cruz M, et al. Availability and integration of palliative care at US cancer centers. JAMA 2010;303:1054-61. [PubMed]

- von Gunten CF. Secondary and tertiary palliative care in US hospitals. JAMA 2002;287:875-81. [PubMed]

- Payne R. The integration of palliative care and oncology: the evidence. Oncology (Williston Park) 2011;25:1266. [PubMed]

- Weissman DE, Meier DE. Identifying patients in need of a palliative care assessment in the hospital setting: a consensus report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J Palliat Med 2011;14:17-23. [PubMed]

- Von Roenn JH. Palliative care and the cancer patient: current state and state of the art. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2011;33:S87-9. [PubMed]

- Bruera E, Hui D. Integrating supportive and palliative care in the trajectory of cancer: establishing goals and models of care. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4013-7. [PubMed]

- Bruera E, Hui D. Conceptual models for integrating palliative care at cancer centers. J Palliat Med 2012;15:1261-9. [PubMed]

- Levy MH, Adolph MD, Back A, et al. Palliative care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2012;10:1284-309. [PubMed]

- Gaertner J, Wolf J, Hallek M, et al. Standardizing integration of palliative care into comprehensive cancer therapy--a disease specific approach. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1037-43. [PubMed]

- Gaertner J, Wolf J, Ostgathe C, et al. Specifying WHO recommendation: moving toward disease-specific guidelines. J Palliat Med 2010;13:1273-6. [PubMed]

- Hui D, Kim YJ, Park JC, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: a systematic review. Oncologist 2015;20:77-83. [PubMed]

- Kloke M, Scheidt H. Pain and symptom control for cancer patients at the University Hospital in Essen: integration of specialists’ knowledge into routine work. Support Care Cancer 1996;4:404-7. [PubMed]

- Strasser F, Sweeney C, Willey J, et al. Impact of a half-day multidisciplinary symptom control and palliative care outpatient clinic in a comprehensive cancer center on recommendations, symptom intensity, and patient satisfaction: a retrospective descriptive study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2004;27:481-91. [PubMed]

- Gaertner J, Wolf J, Scheicht D, et al. Implementing WHO recommendations for palliative care into routine lung cancer therapy: a feasibility project. J Palliat Med 2010;13:727-32. [PubMed]

- Hydeman J. Improving the integration of palliative care in a comprehensive oncology center: increasing primary care referrals to palliative care. Omega (Westport) 2013;67:127-34. [PubMed]

- Shamieh O, Hui D. A comprehensive palliative care program at a tertiary cancer center in Jordan. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:238-42. [PubMed]

- Dev R, Del Fabbro E, Miles M, et al. Growth of an academic palliative medicine program: patient encounters and clinical burden. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:261-71. [PubMed]

- Yennurajalingam S, Atkinson B, Masterson J, et al. The impact of an outpatient palliative care consultation on symptom burden in advanced prostate cancer patients. J Palliat Med 2012;15:20-4. [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Jackson VA, Billings JA, et al. Phase II study: integrated palliative care in newly diagnosed advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:2377-82. [PubMed]

- Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer 2014;120:1743-9. [PubMed]

- Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: what’s in a name?: a survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive cancer center. Cancer 2009;115:2013-21. [PubMed]

- Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D, et al. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist 2011;16:105-11. [PubMed]

- Wentlandt K, Krzyzanowska MK, Swami N, et al. Referral practices of oncologists to specialized palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4380-6. [PubMed]

- Maciasz RM, Arnold RM, Chu E, et al. Does it matter what you call it? A randomized trial of language used to describe palliative care services. Support Care Cancer 2013;21:3411-9. [PubMed]

- Davis MP, Strasser F, Cherny N, et al. MASCC/ESMO/EAPC survey of palliative programs. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:1951-68. [PubMed]

- Yoong J, Park ER, Greer JA, et al. Early palliative care in advanced lung cancer: a qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:283-90. [PubMed]

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741-9. [PubMed]

- Prince-Paul M, Burant CJ, Saltzman JN, et al. The effects of integrating an advanced practice palliative care nurse in a community oncology center: a pilot study. J Support Oncol 2010;8:21-7. [PubMed]

- Dyar S, Lesperance M, Shannon R, et al. A nurse practitioner directed intervention improves the quality of life of patients with metastatic cancer: results of a randomized pilot study. J Palliat Med 2012;15:890-5. [PubMed]

- Muir JC, Daly F, Davis MS, et al. Integrating palliative care into the outpatient, private practice oncology setting. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:126-35. [PubMed]

- Johnston B, Buchanan D, Papadopoulou C, et al. Integrating palliative care in lung cancer: an early feasibility study. Int J Palliat Nurs 2013;19:433-7. [PubMed]