The self-perceived palliative care barriers and educational needs of clinicians working in hospital primary care teams and referral patterns: lessons learned from a single-center survey and cohort study

Introduction

Within the generalist-plus-specialist palliative care model (1-3), all clinicians (both nurses and physicians) are expected to provide primary palliative care for patients with advanced illnesses, consisting of managing physical and psychological problems and having conversations about prognosis, treatment goals and life-sustaining treatments (2,3). However, in daily practice, hospital primary care clinicians often received limited education on palliative care and therefore focus mainly on treating the disease (4-8). This may prevent them from adequately caring for their patients, including not recognizing when to integrate a palliative care approach alongside disease-directed treatments and when to involve palliative care specialists (9). Hospital-based palliative care consultation teams (PCCTs) are increasingly available to support primary care teams and to provide specialist palliative care for patients with complex needs, such as refractory symptoms or difficult psychosocial and existential problems. To optimize hospital-based palliative care it is important that PCCTs not only invest in clinical care but also in nonclinical activities to improve the care provided by primary care teams (1,10). When our PCCT started in 2012, efforts were made to design a comprehensive nonclinical strategy. Core components were educational activities in each hospital department, marketing the added value of the PCCT and implementing palliative care support options for primary care teams. These support options included developing hospital-wide palliative care guidelines, promoting existing national symptom management guidelines and introducing the Surprise Question (11). Our PCCT specialists also trained primary care team clinicians to act as ‘palliative care champions’ (12,13). These champions were educated on diverse palliative care subjects four times per year (during 1.5-hour meetings) and served as palliative care ambassadors within their own hospital department, disseminating knowledge when needed.

Until now, studies have focused on identifying factors that facilitate or hinder palliative care referral (9) and collaboration between primary care teams and PCCTs within clinical patient care (14). None have evaluated how PCCTs can best support clinicians within their hospital to improve their primary palliative care skills. Our study aimed to assess the self-perceived barriers and educational needs of our hospital’s primary care team clinicians in order to tailor our nonclinical activities to meet their support needs. In addition, we assessed their awareness of available palliative care support options and evaluated referral patterns.

We present this study in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1706).

Methods

Context

The Leiden University Medical Center had 25.634 hospital admissions per year in 2017 and a mean of 504 in-hospital deaths per year between 2014 and 2016. The PCCT was initiated in 2012 and consists of nurses, nurse practitioners and physicians specialized in palliative care. Inpatients and outpatients can be referred by physicians and nurses of primary care teams, and by self-referral of patients and their family members. All referred patients are discussed in weekly multidisciplinary team meetings involving PCCT consultants, clinicians from the patient’s primary care team, social workers, liaison nurses, medical psychologists, pharmacologists, spiritual counsellors, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists and pain specialists.

Data collection

Part A: baseline and follow-up survey on barriers, educational needs and awareness of palliative care support options

Shortly after the start of the PCCT in 2012, a survey was sent by email to all medical and nursing managers of the 26 hospital departments providing patient care. The managers were asked to request a number of nurses and physicians to fill out the survey, serving as department representatives (baseline). In 2016, the survey was sent again (follow-up), with the same request. Surveys were filled out anonymously. The survey was developed by the PCCT consultants who based the content on their experiences with supporting primary care clinicians. Face validity and clarity of questions were assessed by a pilot sample of primary care team hospital nurses and physicians and questions were adjusted according to their feedback. The survey consisted of eight open-ended and 26 multiple-choice questions. An English translation of the full survey is provided in Appendix 1.

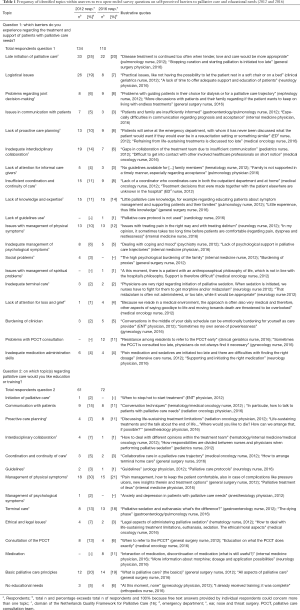

In this study we report the outcomes of two open-ended survey questions on self-perceived barriers to palliative care and educational needs: question 1 “which barriers do you experience regarding the treatment and support of patients with palliative care needs?” and question 2 “on which topic(s) regarding palliative care would you like education or training?”. We also report the outcomes of six multiple-choice questions on awareness and use of palliative care support options, such as the PCCT, national palliative care symptom management guidelines, and departmental palliative care champions.

Part B: cohort study

Data on all patients referred to the PCCT from January 2012 to December 2017 were retrospectively collected from the electronic patient files. One physician (LS) and one nurse practitioner (EN) collected the following data: age, sex, primary diagnosis, referring department, referral date, inpatient or outpatient referral, date of death or last contact and disease phase (disease-directed or symptom-directed at time of referral; registered by a PCCT consultant from June 2014 onwards). Primary diagnosis was categorized into cancer, dementia/frailty, neurological disease, heart/vascular disease, respiratory disease, kidney disease, liver disease and other (15). Survival data were updated until February 6, 2020. Observed survival (OS) was defined from referral until death or last contact. To evaluate timing of referral, OS of referred patients was calculated in those departments that referred at least 10% of referrals from 2012 to 2017. We characterized early palliative care (OS ≥3 months), late palliative care (OS ≥2 weeks to <3 months) and care in the dying phase (OS <2 weeks) to evaluate yearly changes in the timing of referrals.

Part C: clinical prediction of survival at referral

From June 2014 onwards, all physicians were asked at referral if they would be surprised if their patient would die within 1 year, 3 months or 2 weeks to assess their ability to prognosticate.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics board of Leiden University Medical Center (G19.050) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Statistical analysis

Part A: baseline and follow-up survey on barriers, educational needs and awareness of palliative care support options

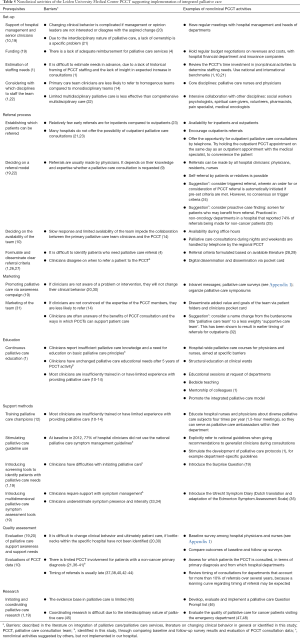

Answers to the open-ended questions were analyzed qualitatively to identify the topics within respondents’ answers. The frequency of identified topics was then analyzed using descriptive statistics. Coding was done independently by a physician (LS) and nurse practitioner (EN) using pre-established codes, based on the Netherlands Quality Framework for Palliative Care (16) (see Table 1). If the answers did not fit the pre-established codes, inductive coding was done using thematic analysis (17). Disagreements were solved by discussion. The final set of codes was shared with other research team members for consensus, to obtain a definitive set of identified topics. Differences between the 2012 and 2016 outcomes of multiple-choice questions were analyzed using either chi-squared (dichotomous variables) or Mann-Whitney U tests (ordinal variables). Differences were considered statistically significant if P values were <0.05.

Full table

Part B: cohort study

Referral characteristics were analyzed descriptively. OS was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Yearly changes in referral timing in frequently referring departments were evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Part C: clinical prediction of survival at referral

OS and predicted survival were compared using weighted Kappa (18).

Results

Part A: baseline and follow-up survey on barriers, educational needs and awareness of palliative care support options

Respondent characteristics

In 2012, 291 primary care team clinicians filled out the survey, representing 92% of hospital departments (24/26 departments). In 2016, 195 clinicians filled out the survey, representing 96% of hospital departments (25/26 departments) (Table S1).

Open-ended question 1 on self-perceived barriers to palliative care

In 2012, 134 survey respondents (46%) and in 2016, 110 respondents (56%) reported on their self-perceived barriers to caring for patients with palliative care needs. All reported topics with illustrative quotes are listed in Table 1. In both years, the topic most often identified was the late initiation of palliative care (25% in 2012 and 20% in 2016). Respondents’ main concerns were that disease-directed treatment is often continued too long. They also mentioned that patients who might benefit from palliative care are often identified too late. It was noted that physicians place too much focus on disease treatment which means that underlying problems that patients have are often not acknowledged.

In 2012, the second most identified topic was logistical issues, reported by 19% of respondents. Especially mentioned was a lack of time to adequately care for patients with palliative care needs. Respondents also reported insufficient resources, for example not being able to admit patients with complex needs because of bed shortages or not being able to offer patients’ family members a bed to stay the night. In the outpatient clinic, a lack of comfortable chairs or beds to enable outpatients with palliative care needs to rest was mentioned. In 2016, the second most identified topic was insufficient general palliative care knowledge, reported by 14% of respondents, such as knowledge on pain management and when to refrain from life-prolonging treatments.

Open-ended question 2 on self-perceived educational needs

In 2012, 61 survey respondents (21%) and in 2016, 72 respondents (37%) reported on their self-perceived educational needs. All reported topics with illustrative quotes are listed in Table 1. In both years, most often mentioned were educational needs on the management of physical symptoms (30% in 2012; 21% in 2016). Clinicians commented on pain management and management of specific non-pain symptoms, like dyspnea, ileus, nausea, anorexia and restlessness. In both years, respondents also often wanted to be educated on basic palliative principles (20% in 2012; 19% in 2016).

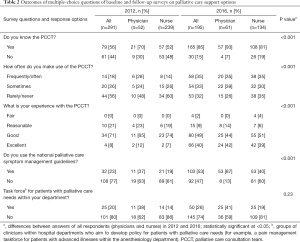

Multiple choice questions on awareness of palliative care support options

Familiarity with the PCCT increased from 56% in 2012 to 85% in 2016 (P<0.001) (Table 2). In 2012, 18% of the respondents consulted the PCCT frequently and this increased to 35% in 2016. Likewise, the number of respondents who rarely or never consulted the PCCT decreased from 56% in 2012 to 32% in 2016 (P<0.001). In 2012, 8% of respondents appraised their experiences with the PCCT as excellent and 71% as good, and this increased to 40% and 49% of respondents in 2016 (P<0.001). Use of national palliative care symptom management guidelines among physicians increased from 37% to 87% (P<0.001). In 2016, 49% of respondents were aware of the presence of a palliative care champion nurse and/or physician within their own department.

Full table

Part B: cohort study

Palliative care referral characteristics

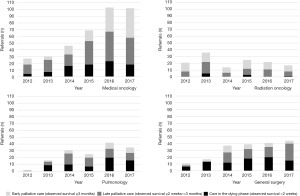

From 2012 to 2017, clinicians referred 1,404 patients to the PCCT. Referral, patient and follow-up characteristics are summarized in Table 3. Eighty-six percent of referred patients were primarily diagnosed with cancer, 43% were younger than 65 years and 23% were outpatients. Referrals increased by a mean of 28% per year (Figure 1). The proportion of referrals for non-cancer patients compared to overall referrals per year increased by a mean of 2.7% per year; 14% of referrals were non-cancer patients in 2012 and 18% in 2017.

Full table

Patients were referred most frequently by clinicians working in medical oncology, radiation oncology, pulmonology, and general surgery (see Figure S1 for referrals per hospital department per year).

Timing of referral

At study closure, 98% of referred patients had died (n=1,373). The median OS since referral was 0.9 (range, 0–83.3) months. When looking at timing of referral, clinicians referred 26% of patients early (OS after referral ≥3 months), 37% late (OS after referral ≥2 weeks and <3 months) and 37% in the dying phase (OS after referral <2 weeks) (Table 3).

Median survival differed between the four main referring departments (medical oncology: median 1.5 months, range 0–54.0 months; radiation oncology: median 3.2 months, range 0–83.3 months; pulmonology: median 0.7 months, range 0–38.0 months; and general surgery: median 0.5 months, range 0–37.9 months). The proportion of early palliative care referrals (OS after referral ≥3 months) increased over time only in referrals made by medical oncology clinicians (P=0.016) (Figure 2).

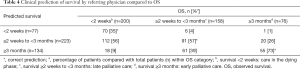

Part C: clinical prediction of survival at referral

Referring physicians predicted survival in 434 patients. Survival was correctly predicted in 50% of patients and overestimated in 44% (kappa 0.36, 95% CI: 0.30–0.42) (Table 4). Survival predictions were least accurate in patients with an OS of less than 2 weeks.

Full table

Discussion

In our study, self-perceived barriers to palliative care among primary care team clinicians were the late initiation of a palliative care approach and a lack of palliative care knowledge within their own team. Respondents reported the need for education mainly in physical symptom management and basic palliative care principles. Both barriers and educational needs were largely similar in the two surveys with 5 years in between despite increased awareness and use of palliative support options and a steady yearly increase of PCCT referrals. This may be due to the high turnover of junior clinicians working in our teaching hospital. In addition, clinicians may not be able to develop routine or build confidence in providing palliative care because they care for patients with advanced illnesses too infrequently. Barriers and educational needs also persisted despite PCCT efforts to target these topics through their nonclinical activities from 2012 onwards. An overview of all our nonclinical activities is provided in Table 5. We based these activities on the 2012 and 2016 survey outcomes and added information from the literature on barriers for PCCT integration (1,10,14,19,49), and on changing clinical behavior (20,30).

Full table

The identified self-perceived barriers and educational needs are in line with reported topics identified in interview studies among hospital primary care team physicians and nurses (50,51). Although late initiation of palliative care was the most reported barrier in our surveys, only one clinician in 2012 mentioned this as an educational need. This suggests a lack of awareness among clinicians that knowing when to initiate a palliative care approach is a distinctive skill that can be improved through education and support. Moreover, the survey answers reported by respondents regarding the initiation of palliative care suggest that primary care team clinicians are insufficiently aware of integrated palliative care, where palliative care is provided alongside disease-directed treatment (52,53). The traditional approach of starting palliative care only after all disease-directed treatment is complete has been identified as a barrier to initiating palliative care in a timely manner (4) and to collaborating with a PCCT (14,54). Our PCCT focused on teaching primary care clinicians how to identify patients who might benefit from palliative care. For example, to increase their awareness, from 2014 onwards, upon each referral request the referring physician is asked to answer the 1 year, 3 months and 2-week Surprise Question (11). To improve symptom management, the PCCT introduced the Dutch version of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) (33,55).

Combining referral patterns with the survey outcomes provides directions for how to improve hospital-based palliative care. Evaluation of our referral characteristics confirmed that clinicians tend to seek less PCCT support for non-cancer patients than they do for cancer patients (21,36-41). It is easier to identify palliative care needs in cancer patients because they usually have steady disease progression with a distinct terminal phase. In contrast, patients with organ failure usually decline gradually with acute exacerbations that may or may not lead to death, and death is often seemingly unexpected (53,56-58). Positively, a small increase in referral of non-cancer patients was observed over the years in our hospital, which is in line with a recent evaluation of 88 US PCCTs (39).

Difficulties initiating palliative care are probably related to the overestimation of survival, both in this study and previous evaluations (59-61). In our study, referrers were more likely to overestimate the survival of patients who survived less than 2 weeks after referral. Only a quarter of patients were referred ≥3 months before death. After referral, our patients lived a median of 27 days, which is comparable with other reports (range, 12–44 days) (37,38,40,42-44). Initiating palliative care early (expected survival ≥3 months) is important, since it improves quality of life and survival and reduces in-hospital deaths, emergency room visits, and hospitalizations in the last phase of life (62,63). Positively, our medical oncology clinicians referred an increasing proportion of their patients for early palliative care (OS ≥3 months) over time. This learning curve regarding the timing of referral was only observed in this department, which may be explained by the intensive collaboration between the PCCT and medical oncology clinicians, alongside ample attention in their field for integrated palliative care in general (22,28,49). Additional nonclinical activities to improve PCCT referrals and timing thereof are presented as suggestions in Table 5. The overview of nonclinical activities in Table 5 may help other PCCTs to plan and improve their nonclinical strategies.

Strengths and limitations

Our study combines data on self-perceived palliative care barriers and educational needs of clinicians and referral patterns. This information has allowed us to suggest ways to explain referral patterns and to improve hospital-based palliative care. Although this is a single-center study with a specific organization of palliative care, the identified barriers, educational needs and referral patterns are similar to those reported in previous studies. Thus, other PCCTs may find our outcomes helpful to further integrate palliative care into their hospitals. A limitation is that PCCT members analyzed the qualitative survey data on their own performance, which may be a source of bias. Furthermore, clinicians who filled out the surveys may have had a higher affinity to palliative care than non-responders, which may have affected the survey results (non-response bias). Registration bias may also be present because of the retrospective nature of the referral analysis.

Conclusions

Despite increased awareness and use of available palliative care support options, self-perceived barriers and educational needs of primary care team clinicians persisted after 5 years of clinical and nonclinical PCCT activities. Primary care teams usually referred late for specialist palliative care and tended to overestimate survival at referral.

Therefore, we recommend that PCCTs focus their nonclinical activities on improving general palliative care knowledge among primary care team clinicians. PCCTs should especially support hospital clinicians to identify patients who might benefit from palliative care in a timely manner.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Ilse Hermsen, Mary-Joanne Verhoef, Manon Boddaert and all members of the Leiden University Medical Center Palliative Care Consultation Team.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1706

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1706

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1706). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Leiden University Medical Center (G19.050) and individual consent for this retrospective analysis was waived.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Henderson JD, Boyle A, Herx L, et al. Staffing a specialist palliative care service, a team-based approach: expert consensus white paper. J Palliat Med 2019;22:1318-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care-creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Gunten CF. Secondary and tertiary palliative care in US hospitals. JAMA 2002;287:875-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aldridge MD, Hasselaar J, Garralda E, et al. Education, implementation, and policy barriers to greater integration of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med 2016;30:224-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carrasco JM, Lynch TJ, Garralda E, et al. Palliative care medical education in european universities: a descriptive study and numerical scoring system proposal for assessing educational development. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:516-23.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Centeno C, Garralda E, Carrasco JM, et al. The palliative care challenge: analysis of barriers and opportunities to integrate palliative care in Europe in the View of National Associations. J Palliat Med 2017;20:1195-204. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Bruin J, Verhoef MJ, Slaets JPJ, et al. End-of-life care in the Dutch medical curricula. Perspect Med Educ 2018;7:325-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pieters J, Dolmans D, Verstegen DML, et al. Palliative care education in the undergraduate medical curricula: students' views on the importance of, their confidence in, and knowledge of palliative care. BMC Palliat Care 2019;18:72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmed N, Bestall JC, Ahmedzai SH, et al. Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals. Palliat Med 2004;18:525-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weissman DE. Improving care during a time of crisis: the evolving role of specialty palliative care teams. J Palliat Med 2015;18:204-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Downar J, Goldman R, Pinto R, et al. The "surprise question" for predicting death in seriously ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2017;189:E484-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Witkamp FE, van Zuylen L, van der Rijt C, et al. Effect of palliative care nurse champions on the quality of dying in the hospital according to bereaved relatives: A controlled before-and-after study. Palliat Med 2016;30:180-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Witkamp FE, Van Der Heide A, Van Der Rijt CCD, et al. Effect of a palliative care nurse champion program on nursing care of dying patients in the hospital: a controlled before and after study. J Nurs Health Stud 2017;2:20.

- Firn J, Preston N, Walshe C. What are the views of hospital-based generalist palliative care professionals on what facilitates or hinders collaboration with in-patient specialist palliative care teams? A systematically constructed narrative synthesis. Palliat Med 2016;30:240-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spict.org.uk. Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool. (cited 2019 Apr 29). Available online: https://www.spict.org.uk/the-spict/

- Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Center (IKNL) and Palliactief. Netherlands Quality Framework for Palliative Care. The Netherlands, 2017.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77-101. [Crossref]

- Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 1968;70:213-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krug E, Kelley E, Loring B, et al. Planning and implementing palliative care services: a guide for programme managers. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016.

- Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet 2003;362:1225-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Netherlands Comprehensive Cancer Center (IKNL). Palliatieve zorg in Nederlandse ziekenhuizen. The Netherlands, 2019.

- Hui D, Hannon BL, Zimmermann C, et al. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: Team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:356-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scibetta C, Kerr K, Mcguire J, et al. The costs of waiting: implications of the timing of palliative care consultation among a cohort of decedents at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med 2016;19:69-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kistler EA, Stevens E, Scott E, et al. Triggered palliative care consults: a systematic review of interventions for hospitalized and emergency department patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:460-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fromme EK, Bascom PB, Smith MD, et al. Survival, mortality, and location of death for patients seen by a hospital-based palliative care team. J Palliat Med 2006;9:903-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, Mori M, Watanabe SM, et al. Referral criteria for outpatient specialty palliative cancer care: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 2016;17:e552-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, Meng YC, Bruera S, et al. Referral criteria for outpatient palliative cancer care: a systematic review. Oncologist 2016;21:895-901. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruera E, Hui D. Conceptual models for integrating palliative care at cancer centers. J Palliat Med 2012;15:1261-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Highet G, Crawford D, Murray SA, et al. Development and evaluation of the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT): a mixed-methods study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014;4:285-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grol R, Wensing M. What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Med J Aust 2004;180:S57-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McDarby M, Carpenter BD. Barriers and facilitators to effective inpatient palliative care consultations: a qualitative analysis of interviews with palliative care and nonpalliative care providers. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2019;36:191-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dalal S, Palla S, Hui D, et al. Association between a name change from palliative to supportive care and the timing of patient referrals at a comprehensive cancer center. Oncologist 2011;16:105-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Baan FH, Koldenhof JJ, de Nijs EJ, et al. Validation of the dutch version of the edmonton symptom assessment system. Cancer Med 2020;9:6111-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laugsand EA, Sprangers MA, Bjordal K, et al. Health care providers underestimate symptom intensities of cancer patients: a multicenter European study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okuyama T, Akechi T, Yamashita H, et al. Oncologists' recognition of supportive care needs and symptoms of their patients in a breast cancer outpatient consultation. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2011;41:1251-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Erlenwein J, Geyer A, Schlink J, et al. Characteristics of a palliative care consultation service with a focus on pain in a German university hospital. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13:45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamal AH, Swetz KM, Carey EC, et al. Palliative care consultations in patients with cancer: a mayo clinic 5-year review. J Oncol Pract 2011;7:48-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sasahara T, Miyashita M, Umeda M, et al. Multiple evaluation of a hospital-based palliative care consultation team in a university hospital: activities, patient outcome, and referring staff's view. Palliat Support Care 2010;8:49-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schoenherr LA, Bischoff KE, Marks AK, et al. Trends in hospital-based specialty palliative care in the United States from 2013 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e1917043 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vinant P, Joffin I, Serresse L, et al. Integration and activity of hospital-based palliative care consultation teams: the INSIGHT multicentric cohort study. BMC Palliat Care 2017;16:36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- von Gunten CF, Camden B, Neely KJ, et al. Prospective evaluation of referrals to a hospice/palliative medicine consultation service. J Palliat Med 1998;1:45-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng WW, Willey J, Palmer JL, et al. Interval between palliative care referral and death among patients treated at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med 2005;8:1025-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kozlov E, Carpenter BD, Thorsten M, et al. Timing of palliative care consultations and recommendations: understanding the variability. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2015;32:772-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Osta BE, Palmer JL, Paraskevopoulos T, et al. Interval between first palliative care consult and death in patients diagnosed with advanced cancer at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med 2008;11:51-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abernethy AP, Aziz NM, Basch E, et al. A strategy to advance the evidence base in palliative medicine: formation of a palliative care research cooperative group. J Palliat Med 2010;13:1407-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vergroesen D, Verhoef M, Horeweg N, et al. OP60 Evaluation and further development of a dutch question prompt list on palliative care from the perspective of patients and family. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019;9:A20.

- Verhoef MJ, de Nijs E, Horeweg N, et al. Palliative care needs of advanced cancer patients in the emergency department at the end of life: an observational cohort study. Support Care Cancer 2020;28:1097-107. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verhoef MJ, de Nijs EJ, Ootjers CS, et al. End-of-life trajectories of patients with hematological malignancies and patients with advanced solid tumors visiting the emergency department: the need for a proactive integrated care approach. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2020;37:692-700. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, Bruera E. Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13:159-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCourt R, James Power J, Glackin M. General nurses' experiences of end-of-life care in the acute hospital setting: a literature review. Int J Palliat Nurs 2013;19:510-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kawaguchi S, Mirza R, Nissim R, et al. Internal medicine residents' beliefs, attitudes, and experiences relating to palliative care: a qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2017;34:366-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lynn J, Adamson DM. Living well at the end of life. Adapting health care to serious chronic illness in old age. Washington: Rand Health, 2003.

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005;330:1007-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez KL, Barnato AE, Arnold RM. Perceptions and utilization of palliative care services in acute care hospitals. J Palliat Med 2007;10:99-110. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, Bruera E. The edmonton symptom assessment system 25 years later: past, present, and future developments. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:630-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, et al. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA 2003;289:2387-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Mitchell G, et al. Palliative care from diagnosis to death. BMJ 2017;356:j878. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Leary N, Tiernan E. Survey of specialist palliative care services for noncancer patients in Ireland and perceived barriers. Palliat Med 2008;22:77-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheon S, Agarwal A, Popovic M, et al. The accuracy of clinicians' predictions of survival in advanced cancer: a review. Ann Palliat Med 2016;5:22-9. [PubMed]

- Glare P, Virik K, Jones M, et al. A systematic review of physicians' survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ 2003;327:195-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- White N, Reid F, Harris A, et al. A systematic review of predictions of survival in palliative care: how accurate are clinicians and who are the experts? PLoS One. 2016;11:e0161407 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G, et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD011129 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vanbutsele G, Pardon K, Van Belle S, et al. Effect of early and systematic integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:394-404. [Crossref] [PubMed]