Self-compassion mediates the perfectionism and depression link on Chinese undergraduates

Introduction

Depression is a common and worldwide mental health problem. According to the prediction of World Health Organization (WHO), this illness will be ranked as the first cause of burden of disease all over the world by 2030 (1). Minor depression will turn out to be critical and full-fledged symptoms if the early intervention is missing (2). It may induce loss of interest in daily life and depressed mood, severely affect the psychosocial function, and diminish the quality of life (3). The incidence rate of this emotional disorder is significantly influenced by the social and cultural factors as well as the genomic and other biological factors (4). The average age of the first onset is 25 years old, and more than 40% of people begin to feel depressive before their twenties (3,5,6). It means that teenagers, especially adolescent university students are more likely to suffer from this negative mood because they are undergoing the growth phase (7). During this growing period, university students are obliged to seek for their further life goals, build up their personalities, and understand their possible responsibilities. These complex issues generally bring about intense pressure ranging from academic, economic, and interpersonal aspects, to the preoccupation with post-graduation life (8). Several studies have reported that the prevalence of depression among university students is higher than other groups (9-11). More importantly, high prevalence of depression has been proved to relate to high risk of suicidal ideation, substance abuse, and acute infectious illnesses (10). This situation seems to be more serious in China due to the one-child policy. Most of Chinese university students have no siblings, and they grew up under the utmost care of the whole family members. This special parenting style directly leads to students’ inability to bear pressure or negative emotions, and consequently accelerates the occurrence of depression (12). Previous studies have indicated that the suicidal ideation in Chinese university students is notably relevant to depressive symptoms, and the progress of depression can obviously aggravate the development of suicidal ideation (2,13). Thus, it is essential to further explore the knowledge of the etiopathogenesis of depressive disorder. With an in-depth understanding of the relationships between different influence factors and depression, it is feasible to develop more appropriate interventions for depression in university students. On top of this, it will be helpful for the students to go through their adolescence period smoothly.

As one of the critical causes of depression, the perfectionism is considered to have contradictory effects on depression because of its two different categories. The adaptive perfectionism is also called ‘positive striving perfectionism’, and it has healthy impacts and is not related to psychopathology (14). It helps people to set reachable targets and emphasize achieving success during the process, which will decrease the occurrence rate of depression (15,16). However, the maladaptive perfectionists generally present high levels of self-criticism, suffering from negative evaluation, and concerning about mistakes, which results in a series of psychopathological changes (17,18). It may accelerate the progress of depression since maladaptive perfectionists prefer to pursue unrealistic goals and they’re motivated by avoiding failure (19,20). In order to explore how the perfectionism affects depression, lots of empirical studies on mediator or moderator effects within them have been carried out in recent years. Self-esteem, social support, optimism, rumination, immature defenses, self-compassion and maladaptive coping strategies have been respectively reported to be the role of mediator among perfectionism and depression (21-25). On the other hand, the moderators include life meaning, self-efficacy, self-compassion, and social support (26-29). Some of the factors mentioned above have been proved to have both mediating effects and moderating effects, such as self-efficacy, self-compassion, and social support.

Compared with other factors, self-compassion has seldom been studied in the link between perfectionism and depression. The concept of self-compassion was first advanced by Neff with a definition of ‘unconditional kindness and comfort while embracing the human experience, difficult as it is’ (30,31). According to Neff, self-compassion is comprised of three primary components which is self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness. These parts contribute to maintaining kind to oneself and accepting flaws and disappointments (30). Due to these advantages, self-compassion may support people to protect against negative emotions generated by maladaptive perfectionism and highlight the positive effects of adaptive perfectionism. Through this way, the depression level could decrease to some extent. Several studies have demonstrated that there is an inverse relationship between self-compassion and depression (32-34). An Australian group investigated the effect of self-compassion in the development of depression. The results indicated that self-compassion weakened the strength of the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and depression in both adolescent and adult groups as a moderator (28). A study on American undergraduates proved that self-compassion could act as a mediator in the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and depressive symptoms (35). Zhou et al. enrolled some impoverished Chinese undergraduates in their study to examine the role of self-compassion as a predictor of depression, and they found that higher levels of self-compassion generally predicted lower depression levels. Besides, raising the level of self-compassion may be beneficial to the mental health situation of undergraduates (36).

However, further studies on detailed mechanism of self-compassion as a mediating role in the perfectionism and depression link among Chinese university students are scarce. Due to the social and cultural differences (e.g., home environment, educational policies and parenting styles) between China and the western countries, exploring the knowledge of self-compassion in Chinese students is indispensable. For most of Chinese adolescents, their college years account for the quite critical period of growing into independent and mature individuals. Therefore, cultivating strong and healthy mental traits is pivotal in their personality shaping and future life planning. It was hypothesized that self-compassion would have impacts in this process. More specifically, self-compassion would positively correlate with adaptive perfectionism, and negatively correlate with maladaptive perfectionism. Meanwhile, self-compassion was assumed to mediate the relationship between perfectionism and depression among Chinese undergraduates.

We present the following article in accordance with the MDAR reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1582).

Methods

Participants

A total of 540 freshmen and sophomores (398 male, 142 female) from three universities in China were recruited in this study. They major in mechanical engineering, electrical engineering, automation, industrial design, and aeronautical and manufacturing engineering. By excluding invalid questionnaires, 451 valid questionnaires were left for the future analysis. Among them, 333 participants (73.84%) were identified as male, and 118 participants (26.16%) were identified as female. Two hundred and two participants (44.79%) were identified as freshmen, and 249 participants (55.21%) were identified as sophomores.

Procedure

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Drum Tower Hospital affiliated to the Medical School of Nanjing University (2020AE02005). Participants completed the questionnaire using the online platform Wenjuanxing. All of the students participated in the research voluntarily. Questionnaires were completed anonymously and confidentiality was guaranteed. All of the participants were informed of the purposes of the study in advance. No financial rewards were offered for participants.

Measures

Perfectionism: a modified 27-item Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (FMPS) developed by Zi and Zhou was employed to evaluate the perfectionism level (37). This revised scale is composed of five subscales, including Concern over Mistakes, Personal Standards, Parental Expectations, Doubts about Actions, and Organization. The first four dimensions is related to the maladaptive perfectionism, and Organization is related to the adaptive perfectionism. Items are responded to by using a scale of 1= almost never to 5= almost always. The internal consistency coefficient reported by Zi and Zhou was 0.64 to 0.81. The coefficient was 0.63 to 0.86 in this study, which means that the scale is valid and reliable for Chinese undergraduates.

Depression: the 20-item Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) was used to measure depression (38). Items are rated on a 4-point scale (1= not true at all; 4= true all the times) evaluating the four common characteristics of depression: the pervasive effect, the physiological equivalents, other disturbances, and psychomotor activities. The total raw scores need to multiply by 1.25 to achieve the Standard Scores, and the cut-off score of 53 is appropriate for Chinese populations (39,40). The internal consistency coefficient of this scale was 0.84 in this study.

Self-compassion: self-compassion was evaluated by using the modified Chinese version of the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS) originally developed by Neff (41). The Chinese version was reported by Chen et al., and the reliability and validity were confirmed (36,42). On this basis, Hou added 4 lie detection questions to screen invalid responses. The internal consistency coefficient was 0.83 and the test-retest reliability was 0.79 over 3 weeks (43). The 30-item scale comprises six subscales: Self-Kindness, Self-Judgement, Common Humanity, Isolation, Mindfulness and Over-Identification. Participants indicate their agreement with items by using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The internal consistency coefficient of this scale was 0.82 in this study.

Statistical analysis

All of the data in this study were analyzed by using SPSS 23.0 (IBM, USA). The descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation analysis, and multiple linear regression were used to achieve the means, standard deviations, correlations between each variable, and the prediction effect of perfectionism and self-compassion on depression. The mediation effect of self-compassion was assessed by hierarchical multiple regression using the Hayes PROCESS macro 3.1 for SPSS (44). For the simple mediation effect analysis, Model 4 was selected in PROCESS. Indirect effects were evaluated using a bias-corrected bootstrapping procedure. The 95% confidence interval (CI) did not include 0, and it represented that the mediation effect was significant.

Results

Preliminary analyses

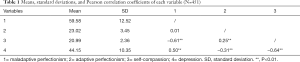

The skewness and kurtosis values for the three scales were all within the acceptable range of −2 to +2 (45). The means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlation coefficients were demonstrated in Table 1. According to the results, maladaptive perfectionism had a significant negative correlation with self-compassion (r=−0.61), and a significantly positive correlation with depression (r=0.50). Adaptive perfectionism had a significant positive correlation with self-compassion (r=0.25), and a notably negative relationship with depression (r=−0.31). A significant negative correlation was existed between self-compassion and depression (r=−0.64). No significant differences were found in different genders or grades among these variables.

Full table

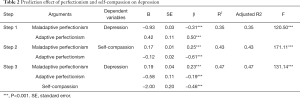

Regression analyses

Three steps were applied in this examination. According to Table 2, the perfectionism and depression were entered in the first step, and 35% of the variance can be explained in predicting depression (R2=0.35, adjusted R2=0.35, F=120.50, P<0.001). The self-compassion and perfectionism were entered in the second step, and they accounted for 43% of the variance (R2=0.43, adjusted R2=0.43, F=171.11, P<0.001). The self-compassion, adaptive perfectionism, and maladaptive perfectionism were entered in the third step, and 47% of the variance can be explained (R2=0.47, adjusted R2=0.47, F=131.14, P<0.001). The standardized beta coefficients demonstrated that the self-compassion and adaptive perfectionism were negative predictors (β=−0.46 and β=−0.19, respectively, P<0.001). The maladaptive perfectionism was a positive predictor for depression (β=0.23, P<0.001). Among them, self-compassion had the largest contribution to predict depression.

Full table

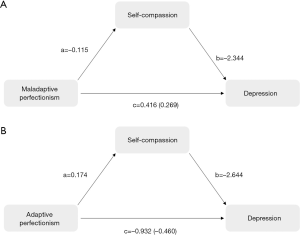

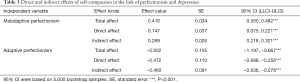

Mediation effects

The mediation models of maladaptive perfectionism and adaptive perfectionism were exhibited in Figure 1, the detailed results were shown in Table 3. For the maladaptive perfectionism (Figure 1A), three paths were constructed, including path a (maladaptive perfectionism to self-compassion), path b (self-compassion to depression), and path c (maladaptive perfectionism to depression). Significant effect can be found for all paths in this model. In detail, the participants with higher scores of maladaptive perfectionism usually had lower self-compassion scores (a=−0.115, 95% CI, −0.128 to −0.101, P<0.001). Compared with participants reporting lower scores of self-compassion, participants reporting higher scores of self-compassion demonstrated lower level of depression (b=−2.344, 95% CI, −2.729 to −1.960, P<0.001). In path c , the bootstrapping indicated that the effect value of indirect path of linking maladaptive perfectionism to depression via self-compassion was 0.269 (path ab, 95% CI, 0.218 to 0.321, P<0.001), and the direct effect between maladaptive perfectionism and depression was 0.147 (95% CI, 0.075 to 0.221, P<0.001). Additionally, higher scores of maladaptive perfectionism was related to higher scores of depression, and the total effect was 0.416 (the combination of direct and indirect effects, 95% CI, 0.350 to 0.482, P<0.001).

Full table

The model of adaptive perfectionism (Figure 1B) also contained three paths, and all the paths shown significant effects. Briefly, higher level of adaptive perfectionism was correlated to higher level of self-compassion (a=0.174, 95% CI, 0.113 to 0.235, P<0.001). Participants with higher scores of self-compassion reported lower scores of depression (b=−2.644, 95% CI, −2.960 to −2.329, P<0.001). The indirect effect between adaptive perfectionism and depression was −0.460 (path ab, 95% CI, −0.636 to −0.278, P<0.001), and the direct effect was −0.472 (95% CI, −0.688 to −0.256, P<0.001). Therefore, the students reporting higher scores of adaptive perfectionism manifested greater approval of depression than those who reported lower scores on adaptive perfectionism, and the total effect was −0.932 (95% CI, −1.197 to −0.667, P<0.001).

On the basis of the results mentioned above, we can conclude that the self-compassion partially mediates the relationship between perfectionism and depression.

Discussion

The prevalence of depression is extremely high among university students as they’re going through the critical stage of personal growth. About 30% of the university students worldwide reported depression, and the incidence rate of depression is 24% in Chinese university undergraduates (9,10). Considering that the depression has induced abnormal social relationship, increased weariness, and even self-injury behavior, it is necessary to clarify the generative mechanism and find effective psychological interventions (46). Although numerous factors and intervention methods have been studied in this field, it is still crucial to conduct these studies in China because of the cultural differences between China and western countries. As far as we know, it is the first study that exploring the relationships between perfectionism, self-compassion and depression in the context of Chinese university students. Our results demonstrated that the maladaptive perfectionism had a positive correlation with depression, and higher level of maladaptive perfectionism can predict higher level of depression. Adaptive perfectionism and self-compassion can be regarded as negative predictors for depression. Furthermore, self-compassion can act as a mediating factor in the link of perfectionism and depression among undergraduates. These results supported our hypotheses, and revealed one of the possible mechanisms of perfectionism on depression. Therefore, we believed that self-compassion may be a potential target for psychological intervention to help alleviate depressive symptoms.

For university students, college life will directly confront them with unacquainted issues, such as grade points, interpersonal relationships, and job prospects. These differences and changes in physiology, cognition, and environment may cause students’ psychological conflicts (47), which will further lead to poor academic performance, drug abuse, physical health problems, and behavior problems in adulthood and later life (48). In addition to the common factors mentioned above, the particular social environment in China makes college students more likely to suffer from mental health problems. Until the year of 2016, the One-Child Policy has been implemented for about 40 years, and it directly gave rise to the emergence of “the loneliest” generation (49). Thus, most of the contemporary Chinese college students, and even their parents have no siblings in their families. The experience of growing up with all the family members’ accompany and concern made them more egocentric and less cooperative (50). Therefore, when they leave home to start the college life, they’re more likely to feel lonely than their peers who have siblings (51). All of these negative factors will work together to intensify the mental health issues. More seriously, few people can give aid to them to overcome the predicament. As a matter of fact, the clinical resources of mental health care are badly limited, and the ratio of clinical psychiatrists to patients is 1.7 per 100,000 (52). Under such circumstances, Chinese college students who are experiencing this difficult period cannot obtain effective help from their parents who have ever been in the same trouble, nor can they access to effective treatment from clinical psychologists. Fostering the awareness of self-compassion from childhood, and guiding them to be more tolerant and peaceful when encountering difficulties and obstacles during adolescence may be conductive to the cultivation of undergraduates’ mental health.

Several studies have proved that self-compassion has advantages in improving mental health outcomes, including suicidal behavior, depression, and eating disorders (53-55). However, most of these researches focused on the adult, and the effects of self-compassion on adolescents, especially university undergraduates have been rarely reported (56,57). As a potent factor to inhibit the development of depression and improve the depressive symptoms, self-compassion plays an important role in the depression intervention of university undergraduates (58). Due to the influence of traditional Chinese culture, people tend to be more conservative and introverted. It’s difficult for them to share their psychological feelings and mental experiences with strangers, let alone the psychiatrists or counselors. Worse still, mental disorder has been stigmatized in China for a long time, making patients refuse to ask for help (59). However, it is inevitable for college students to be faced with setbacks and failures during their tough period of individual growth. The existence of maladaptive perfectionism would induce the improper attitude towards these failures, such as extreme self-criticism, excessive personal standards, and dissatisfaction with their own performance, thereby further exacerbating the negative impacts of negative emotions (35,60).

Studies on clinical and community samples have shown that there is a significant relationship between perfectionism and depression, and the occurrence of maladaptive perfectionism is usually earlier than depression (61-63). This situation will be gradually aggravated during the individual development (64). Evidences have been presented to certify that perfectionism can predict the later episodes development of major depression, and later alternation in depression except neuroticism (17,65). For the patients with depression induced by maladaptive perfectionism, the three dimensions of self-compassion can buffer the stress, the harshness, and self-criticism associated with maladaptive perfectionism by training self-kindness and self-acceptance (66). Remarkably, self-compassion is not only a psychological intervention method, but also a kind of personal skill that can be improved by practice (30). Studies have proved that self-compassion can collaborate with adaptive perfectionism to defeat the stress-induced effects on physiological stress responses, and protect individuals from the negative effects of stress events (58). With the assistance of self-compassion, it is easier for university undergraduates to build up self-recognition and mental resilience in their vital growth period of developing self-identification and self-efficacy (67).

Therefore, taking the development of self-compassion as one of the interventions on maladaptive perfectionism and depression is necessary for mental health education of Chinese university students. The acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) has been proved effective in strengthening individual’s self-compassion, especially for patients with psychological distress, depression, and anxiety (68). In addition, the mindful self-compassion course based on Neff’s conceptualization can also improve self-compassion, and the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress are significantly decreased after 6 months (69). During pandemics, the incidence of depression in university students may increase due to the fear of the novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) and the school closure (70). Setting up online courses on self-compassion education will be meaningful for students to tide over the tough time. An Australian group has reported that a 6-week online self-compassion cultivation program can notably improve the self-compassion and happiness, as well as relieving the symptoms of depression, stress, and emotion regulation difficulties (71-73). It follows that the self-compassion education can be implemented both in face-to-face and online approaches, which greatly expands the application scope in university students’ mental health regulation.

There are still some limitations in this study. First of all, the original Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale was designed on college lowerclassmen. To ensure the accuracy of the study, we did not enroll the junior and senior students in the research. In order to further exploring the mediation effect of self-compassion in the relationship between perfectionism and depression within the whole group of college students, other types of perfectionism scales should be employed in the future study, such as the Hewitt-Flett Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (HMPS), and the Revised Almost Perfect Scale (APS-R). Another limitation is that most of the participants major in engineering, and students in other majors should be recruited to make the sample more representative. Enlarging the sample size and recruiting participants from majors of medicine, science, and arts and humanities are in progress.

Conclusions

In this study, we explore the mediation effect of self-compassion in the link of perfectionism and depression among Chinese university undergraduates. More than 500 college students are enrolled in the research. The modified FMPS, the SDS, and the modified SCS are used to exam the level of perfectionism, depression, and self-compassion, respectively. The results indicate that the high level of maladaptive perfectionism correlates with high level of depression, and maladaptive perfectionism acts as a positive predictor of depression. The adaptive perfectionism and self-compassion are negatively correlated to depression, and they are negative predictors of depression. Additionally, self-compassion can partially mediate the relationship between perfectionism and depression in Chinese undergraduates. Thus, it can be seen that self-compassion can be employed as an effective psychological intervention method to relieve the symptoms of depression.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Prof. Liya Zhu, Dr. Zongan Li, and Prof. Wenlai Tang (Nanjing Normal University), and Dr. Longfei Yang (Southeast University) for the collecting of questionnaires. We would like to thank Prof. Huanhuan Li and Dr. Wei Song (Renmin University of China) for the design of the study and the data analysis. This study was supported by Nanjing Science and Technology Development Project (201803026).

Funding: This study was supported by Nanjing Science and Technology Development Project (201803026).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the MDAR reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1582

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1582

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1582). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Drum Tower Hospital affiliated to the Medical School of Nanjing University (2020AE02005). The informed consent for this study cannot be applicable, because the research was carried on in April. During that period, all the students were taking online courses at home. They can’t sign the informed consent in written form. But they were informed of the purposes of the study in advance by their teachers, and the relevant results will only be used for scientific research. The students who submitted the questionnaires were regarded as agree to participate in this study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bygstad-Landro M, Giske T. Risking existence: The experience and handling of depression. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:e514-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang YH, Shi ZT, Luo QY. Association of depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among university students in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6476. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malhi GS, Mann JJ. Depression. Lancet 2018;392:2299-312. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Heim C, Binder EB. Current research trends in early life stress and depression: review of human studies on sensitive periods, gene-environment interactions, and epigenetics. Exp Neurol 2012;233:102-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- DeFilippis M, Wagner KD. Management of treatment-resistant depression in children and adolescents. Paediatr Drugs 2014;16:353-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hasler G. Pathophysiology of depression: do we have any solid evidence of interest to clinicians? World Psychiatry 2010;9:155-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Auerbach RP, Mortier P, Bruffaerts R, et al. WHO World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 2018;127:623-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fu Z, Zhou S, Burger H, et al. Psychological interventions for depression in Chinese university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2020;262:440-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim AK, Kelly SJ, Adams CE, et al. A systematic review of studies of depression prevalence in university students. J Psychiatr Res 2013;47:391-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lei XY, Xiao LM, Liu YN, et al. Prevalence of Depression among Chinese University Students: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0153454. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, et al. Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2016;316:2214-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li ZZ, Li YM, Lei XY, et al. Prevalence of suicidal ideation in Chinese college students: a meta-analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e104368. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li H, Fu R, Zou Y, et al. Predictive Roles of Three-Dimensional Psychological Pain, Psychache, and Depression in Suicidal Ideation among Chinese College Students. Front Psychol 2017;8:1550. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brewer MB, Cantor N, Kerr NL. Personality and social psychology review. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 1997;1:2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Zhang B. The dual model of perfectionism and depression among Chinese University students. S Afr J Psychiatr 2017;23:1025. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mathew J, Dunning C, Coats C, et al. The mediating influence of hope on multidimensional perfectionism and depression. Pers Individ Dif 2014;70:66-71. [Crossref]

- Egan SJ, Wade TD, Shafran R. Perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process: A clinical review. Clin Psychol Rev 2011;31:0-212.

- Dibartolo PM, Li CY, Frost RO. How Do the Dimensions of Perfectionism Relate to Mental Health? Cognit Ther Res 2008;32:401-17. [Crossref]

- Terry-Short LA, Owens RG, Slade PD, et al. Positive and negative perfectionism. Pers Individ Dif 1995;18:663-8. [Crossref]

- Seeliger H, Harendza S. Is perfect good? - Dimensions of perfectionism in newly admitted medical students. BMC Med Educ 2017;17:206. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Senra C, Merino H, Ferreiro F. Exploring the link between perfectionism and depressive symptoms: Contribution of rumination and defense styles. J Clin Psychol 2018;74:1053-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park HJ, Heppner PP, Lee DG. Maladaptive coping and self-esteem as mediators between perfectionism and psychological distress. Pers Individ Dif 2010;48:469-74. [Crossref]

- Gnilka PB, Broda MD. Multidimensional perfectionism, depression, and anxiety: Tests of a social support mediation model. Pers Individ Dif 2019;139:295-300. [Crossref]

- Black J, Reynolds WM. Examining the relationship of perfectionism, depression, and optimism: Testing for mediation and moderation. Pers Individ Dif 2013;54:426-31. [Crossref]

- Fletcher K, Yang Y, Johnson SL, et al. Buffering against maladaptive perfectionism in bipolar disorder: The role of self-compassion. J Affect Disord 2019;250:132-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park HJ, Jeong DY. Moderation effects of perfectionism and meaning in life on depression. Pers Individ Dif 2016;98:25-9. [Crossref]

- Zhang B, Cai T. Moderating effects of self-efficacy in the relations of perfectionism and depression. Studia Psychologica 2012;54:15-21.

- Ferrari M, Yap K, Scott N, et al. Self-compassion moderates the perfectionism and depression link in both adolescence and adulthood. PLoS One 2018;13:e0192022. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou X, Zhu H, Zhang B, et al. Perceived Social Support as Moderator of Perfectionism, Depression, and Anxiety in College Students. Social Behavior & Personality An International Journal 2013;41:1141-52. [Crossref]

- Neff K. Self-Compassion: An Alternative Conceptualization of a Healthy Attitude Toward Oneself. Self Identity 2003;2:85-101. [Crossref]

- Tan P. Self-Compassion: Stop Beating Yourself Up and Leave Insecurity Behind. Psychotherapy in Australia 2012;18.

- Barry CT, Loflin DC, Doucette H. Adolescent self-compassion: Associations with narcissism, self-esteem, aggression, and internalizing symptoms in at-risk males. Pers Individ Dif 2015;77:118-23. [Crossref]

- Bluth K, Campo RA, Futch WS, et al. Age and Gender Differences in the Associations of Self-Compassion and Emotional Well-being in A Large Adolescent Sample. J Youth Adolesc 2017;46:840-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Castilho P, Carvalho SA, Marques S, et al. Self-Compassion and Emotional Intelligence in Adolescence: A Multigroup Mediational Study of the Impact of Shame Memories on Depressive Symptoms. J Child Fam Stud 2016;26:1-10.

- Mehr KE, Adams AC. Self-Compassion as a Mediator of Maladaptive Perfectionism and Depressive Symptoms in College Students. J College Stud Psychother 2016;30:132-45. [Crossref]

- Lihua Z, Gui C, Yanghua J, et al. Self-Compassion and Confucian Coping as a Predictor of Depression and Anxiety in Impoverished Chinese Undergraduates. Psychol Rep 2017;120:627-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fei ZI. The Chinese Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale:An Examination of Its Reliability and Validity. Chinese J Clin Psychol 2006;14:560-3.

- Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1965;12:63-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lei M, Li C, Xiao X, et al. Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Resilience Scale in Wenchuan earthquake survivors. Compr Psychiatry 2012;53:616-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feng Q, Zhang QL, Du Y, et al. Associations of physical activity, screen time with depression, anxiety and sleep quality among Chinese college freshmen. PLoS One 2014;9:e100914. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neff KD. The Development and Validation of a Scale to Measure Self-Compassion. Self Identity 2003;2:223-50. [Crossref]

- Chen J, Yan L, Zhou L. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of Self-compassion Scale. Chinese J Clin Psychol 2011;19:734-6.

- Hou J. The research on undergraduates’ Self-compassion and its relationship with Mental health. Southwest University 2007.

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 2004;36:717-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lomax RG, Hahsvaughn DL. Statistical Concepts, 4th Edition. 2015.

- Regehr C, Glancy D, Pitts A. Interventions to reduce stress in university students: A review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2013;148:1-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Byrne DG, Davenport SC, Mazanov J. Profiles of adolescent stress: The development of the adolescent stress questionnaire (ASQ). J Adolesc 2007;30:0-416.

- Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, et al. Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet 2007;369:1302-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang N, Fan FM, Huang SY, et al. Mindfulness training for loneliness among Chinese college students: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Int J Psychol 2018;53:373-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cameron L, Erkal N, Gangadharan L, et al. Little emperors: behavioral impacts of China's One-Child Policy. Science 2013;339:953-7. [PubMed]

- Lykes VA, Kemmelmeier M. What Predicts Loneliness? Cultural Difference Between Individualistic and Collectivistic Societies in Europe. J Cross Cult Psychol 2013;45:468-90. [Crossref]

- Patel V, Xiao S, Chen H, et al. The magnitude of and health system responses to the mental health treatment gap in adults in India and China. Lancet 2016;388:3074-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelly AC, Vimalakanthan K, Miller KE. Self-compassion moderates the relationship between body mass index and both eating disorder pathology and body image flexibility. Body Image 2014;11:446-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Krieger T, Altenstein D, Baettig I, et al. Self-compassion in depression: associations with depressive symptoms, rumination, and avoidance in depressed outpatients. Behav Ther 2013;44:501-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelliher Rabon J, Sirois FM, Hirsch JK. Self-compassion and suicidal behavior in college students: Serial indirect effects via depression and wellness behaviors. J Am Coll Health 2018;66:114-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zessin U, Dickhäuser O, Garbade S. The Relationship Between Self-Compassion and Well-Being: A Meta-Analysis. Appl Psychol Health Well Being 2015;7:340-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- MacBeth A, Gumley A. Exploring compassion: a meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev 2012;32:545-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pullmer R, Chung J, Samson L, et al. A systematic review of the relation between self-compassion and depressive symptoms in adolescents. J Adolesc 2019;74:210-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shang J, Wei S, Jin J, et al. Mental Health Apps in China: Analysis and Quality Assessment. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019;7:e13236. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu TF, Wei M. Perfectionism and negative mood: The mediating roles of validation from others versus self. J Couns Psychol 2008;55:276-88. [Crossref]

- Enns MW, Cox BJ. Perfectionism, Stressful Life Events, and the 1-Year Outcome of Depression. Cognit Ther Res 2005;29:541-53. [Crossref]

- Sherry SB, Gautreau CM, Mushquash AR, et al. Self-critical perfectionism confers vulnerability to depression after controlling for neuroticism: A longitudinal study of middle-aged, community-dwelling women. Pers Individ Dif 2014;69:1-4. [Crossref]

- Sherry SB, Nealis LJ, Macneil MA, et al. Informant reports add incrementally to the understanding of the perfectionism–depression connection: Evidence from a prospective longitudinal study. Pers Individ Dif 2013;54:957-60. [Crossref]

- Fry PS, Debats DL. Perfectionism and the five-factor personality traits as predictors of mortality in older adults. J Health Psychol 2009;14:513-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith MM, Sherry SB, Rnic K, et al. Are Perfectionism Dimensions Vulnerability Factors for Depressive Symptoms After Controlling for Neuroticism? A Meta-analysis of 10 Longitudinal Studies. Eur J Pers 2016;30:201-12. [Crossref]

- Ian L. Compassion Focused Therapy for People with Bipolar Disorder. Int J Cogn Ther 2010;3:172-85. [Crossref]

- Neff KD, Mcgehee P. Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self Identity 2010;9:225-40. [Crossref]

- Yadavaia JE, Hayes S, Vilardaga R. Using Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to Increase Self-Compassion: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Contextual Behav Sci 2014;3:248-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neff KD, Germer CK. A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. J Clin Psychol 2013;69:28-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tang W, Hu T, Yang L, et al. The role of alexithymia in the mental health problems of home-quarantined university students during the COVID-19 pandemic in China. Pers Individ Dif 2020;165:110131. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finlay-Jones A, Kane R, Rees C. Self-Compassion Online: A Pilot Study of an Internet-Based Self-Compassion Cultivation Program for Psychology Trainees. J Clin Psychol 2017;73:797-816. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Son C, Hegde S, Smith A, et al. Effects of COVID-19 on College Students' Mental Health in the United States: Interview Survey Study. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e21279. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patsali ME, Mousa DPV, Papadopoulou EVK, et al. University students' changes in mental health status and determinants of behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. Psychiatry Res 2020;292:113298. [Crossref] [PubMed]