Assisted dying and palliative care in three jurisdictions: Flanders, Oregon, and Quebec

Introduction

Since 1996 (1), jurisdictions around the world have passed assisted dying laws authorising health professionals to prescribe or administer lethal medications to requesting adults deemed mentally competent and fulfilling certain criteria (2). Assisted dying excites considerable controversy and is understood to create a particular challenge for palliative care (3), which is defined as a field of practice which ‘neither hastens nor postpones’ death (4). Indeed, most palliative care associations explicitly oppose assisted dying in all of its forms (5). We conducted a systematic scoping literature review about the relationship between palliative care and assisted dying in contexts where assisted dying is lawful and found just 16 relevant studies (6). Although there is significant commentary before legalization (7-10), there appears to be very little research on the impact of assisted dying on palliative care once legislation is introduced. Our literature review revealed that there is a need for more in-depth understanding of how palliative care practices interact with the implementation of assisted dying in different cultural and legal contexts. Building on that review, the present study was conducted in Quebec, Flanders and Oregon, three jurisdictions where assisted dying is lawful. Its objective was to explore the relationship of palliative care with assisted dying in these settings, from the perspective of palliative care clinicians and other professionals involved in assisted dying and palliative care.

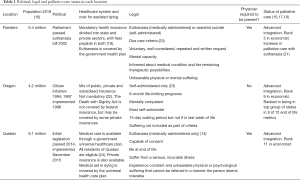

Flanders, Oregon and Quebec were chosen as jurisdictions that have different forms of assisted dying. They have comparable populations (4.1–8.4 million) within larger countries (11). Oregon has the longest experience with assisted dying (1997) (12), followed by Flanders (2002) (13), and Quebec (2015) (14). Although their healthcare systems differ, each jurisdiction has advanced levels of palliative care development (15). See Table 1.

Full table

Methods

Design

This was a multi-sited, qualitative interview study conducted with experienced professionals who were involved in the development of policy, management, and/or delivery of end of life care services.

Sampling, recruitment and ethical considerations

Purposive sampling was undertaken to recruit individuals with a perspective on the development of assisted dying in each location and to include professionals who had clinical, hospital or home-based experiences. Emails were sent inviting potential interviewees considered experts in or experienced with palliative care and assisted dying. Many also forwarded the email to others who responded to the invitation. See Figure 1. Our aim was to interview up to ten individuals in each jurisdiction to have a feasible number to make comparisons and conclusions.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Glasgow, College of Social Sciences. Interviewees received detailed information about the study and provided written informed consent to participate. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Twenty-nine semi-structured interviews lasting 1–2 hours were conducted by one of two authors, SMG or GHK. See interview schedule in Appendix 1. Twenty-four interviews took place face-to-face and five were conducted via Skype or telephone. Interviews were conducted in English, with the exception of three conducted in French and then translated and transcribed into English. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

We conducted an inductive, thematic analysis, following methods described by Braun and Clarke (25,26). SMG coded across all data utilizing QSR NVIVO12 software (27). Open coding was completed and focused on categories relating to the relationship of assisted dying with palliative care practice. Initial codes were subsequently re-categorized, and themes were identified across the data and then according to jurisdiction. To improve trustworthiness, GHK conducted an independent coding, also using QSR NVIVO12. Final themes were agreed upon in collaboration with all authors. The researchers (whose backgrounds include hospice care, social science, ethics and philosophy) undertook reflexive review of data collection and analysis by noting and discussing their own assumptions and potential biases during regular team meetings.

Results

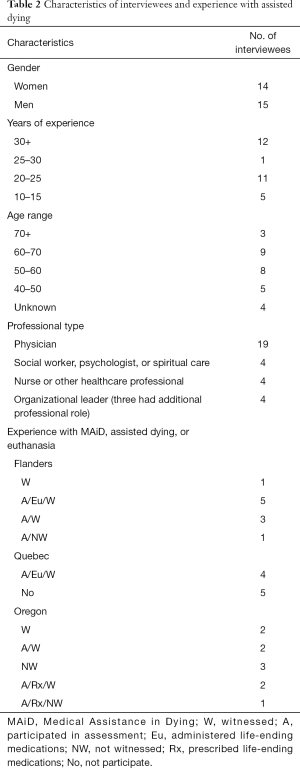

Of 29 professionals interviewed, 10 were from Flanders, 10 from Oregon, 9 from Quebec. Nineteen interviewees were physicians and 10 were other professionals including organizational leaders, nurses, social workers, psychologists or spiritual care counselors. Several interviewees had dual roles. See Table 2.

Full table

A common feature across all the interviews was pronounced concern over lack of public knowledge about, as well as lack of access to, adequate palliative care services. In Oregon and Flanders, a concern was raised that members of the public heard more about assisted dying than they did about palliative care. Moreover, interviewees from Flanders and Quebec indicated a view that assisted dying might become a default choice due to a lack of treatment options, whether perceived or real.

We present results by jurisdiction (Table 3) because of many differences identified in each area. To ensure the interviewees’ anonymity and improve legibility, we have altered some of the language when rendering quotes.

Full table

Flanders

The integrated approach

Our interviewees in Flanders used the term euthanasia to describe both medically administered and self-administered assisted dying. In Flanders, the medically administered form of assisted dying far exceeds the rate of the self-administered form (28). The Belgian situation is often characterized as unique (29) with claims that palliative care and euthanasia developed in tandem and function in an integrated manner (30). Such integration was indicated by our findings, as none of our Flanders interviewees indicated opposition to the law. In general, it was emphasized that euthanasia and palliative care shared the common goal of providing care for the patients:

The aim of euthanasia is not to shorten life (...). The aim of euthanasia for me is to help patient and families to stop the suffering (...). The cultural aims and the cultural drivers for palliative care and for euthanasia, for me, it’s the same (Professional 1).

Furthermore, some interviewees believed that palliative care had improved since euthanasia became lawful because it created a space for discussion and reduced medical paternalism:

I think the law on euthanasia really made the change in the way we are discussing end of life issues with our patients as a physician (...). Previously, it was more like the physician did what he thought he had to do but (did) not discuss this with the patient, his family or with the team (Physician 5).

Although some interviewees reported a concern that palliative care consultations could be ordered in an effort to block or delay efforts to perform euthanasia, others suggested that this did not happen in practice:

Years of experience have documented the opposite—palliative care does not prolong the phase until euthanasia can be done. On the contrary, (palliative care professionals) are doing the major part of euthanasia (Physician 4).

This integrated approach, however, does not mean that euthanasia becomes a special responsibility of palliative care. Interviewees simply expressed a preference for the physician most familiar with the patient—often a GP—to administer euthanasia with the support of palliative care or consult physicians from the group, Life End Information Forum (LEIF) (31).

This is too heavy for a relationship that only has been lasting a few days or weeks (…). Having a relationship of many years with my own patients gives me the right to perform such a heavy act (Physician 6).

It is the strength of the relationship with the patient that made euthanasia acceptable to most of our interviewees.

Discontents in palliative care

Despite the overall perception that palliative care and euthanasia are integrated, some palliative care professionals in Flanders questioned the character of the relationship. One interviewee working in palliative care described an internal conflict between their commitment to a clinical practice aimed at alleviating suffering and a culture that seemed to promote euthanasia. It was indicated, too, that the general population lacked knowledge about palliative care and might erroneously view it as a barrier to accessing euthanasia, thereby creating conflict:

I think palliative caregivers don’t really have a problem with euthanasia, they have a problem with the demand. (Some) patients are brainwashed with the idea that if you try to talk about palliative care, you’re against euthanasia and ‘you want to make me live longer against my will’. You don’t feel as caregiver you have anything to offer, you’re just burdened by the disrespect of the patient or often also the family (Professional 2).

Indeed, as another physician concluded:

It’s becoming quite easy, you know, to do euthanasia (Physician 4).

There were concerns raised that the current medical system allocated too little time and effort to the psychosocial and spiritual aspects of suffering, that palliative care was not always raised as an alternative, and that euthanasia increasingly rests on the principle of autonomy rather than being anchored in a holistic or beneficent practice of medicine:

The palliative care movement made death and even suffering part of life again. Brought it back into the houses. Sometimes I fear that with euthanasia, which is such a beautiful way of stepping out of life, that pain, suffering and dying again is moving out of peoples’ everyday life (Physician 6).

We observe, therefore, a sense of wariness among some of the interviewees with the general Flemish culture being perceived as too ‘euthanasia positive’. Some interviewees argued that euthanasia receives a lot of public and media attention whereas palliative care does not. Consequently, they feared people might request euthanasia without being aware of palliative care options:

(On) television they talk a lot about euthanasia, but they don’t talk that much about palliative care. So, there are many people who are talking about euthanasia without knowing what it is and many people are forgetting that you can die a normal way (Nurse 1).

This fear was crystallized by concerns about ongoing efforts to allow people who do not have life-limiting illnesses to access assisted dying.

Concerns about liberalization of assisted dying laws

Several interviewees in Flanders were apprehensive of euthanasia for reasons other than a terminal diagnosis. Some feared ‘euthanasia on demand’, which was incompatible with their own practice:

If there is no life-threatening disease, I will not offer euthanasia (...) if it’s like for someone who (...) you think still has a life expectancy of a few years, then that’s, for me, not possible to do (Physician 5).

Concern was expressed particularly in regard to psychiatric illness where the professional competencies required to deal with requests fell outside the purview of palliative care:

We are not trained for that (…). It’s not our expertise at all, so to deal with these kinds of patients I think should be within normal psychiatric care (Physician 1).

And similarly:

If you have a terminal patient who is going to die in a few weeks and a doctor has the compassion to practice euthanasia, that’s very different from a psychiatric patient who has chronic depression or maybe schizophrenia (…) who could’ve lived maybe, still 20 or 30 years. The character of this killing is very different from what happens with a strictly terminal patient (Physician 3).

Most interviewees in Flanders suggested that political efforts to inform the public about euthanasia made it seem as if this is a preferable death. Such a discourse appears to cause conflict between those who support further liberalization of the law, and those who do not.

Oregon

Development of death with dignity and the role of hospice

Interviewees from Oregon spoke about ‘hospice’ rather than palliative care and often used ‘Death with Dignity’ when describing the law, which only allows an eligible patient to request from a physician a prescription for a self-administered lethal dose of medication. Hospice, primarily a home-based service in Oregon, is utilized by most individuals who are eligible for Death with Dignity (32). None of the interviewees expressed opposition to the state law ‘The Death with Dignity Act’, which is limited to patients with a life-expectancy of less than 6 months. However, their level of direct experience with it varied: some had been present at such a death while others reported being involved only in assessment for assisted dying.

Some interviewees took the view that hospice organizations did not support the Death with Dignity Act when it passed. As one asserted:

It was always posed: hospice versus physician assisted dying. You could not have both (Professional 5).

One physician suggested that the role of hospice had not been a concern when the law was passed and that there was reticence toward making any changes to the law, for fear that the legislation would be revoked altogether. This position was not unanimously held with others asserting that the relationship between the two was and had in fact always been one of collaboration:

In Oregon, (assisted dying) has never been intended to be an alternative to hospice. In fact, they’ve evolved together as complementary or part of a bigger picture. In Oregon overwhelmingly people have hospice (…) and they also choose Death with Dignity; it’s not one or the other, they’re part of the same thing. That’s why hospice in Oregon, (…) has come to be a supporter because it’s not an alternative it’s complementary (Professional 9).

Interviewees emphasized that a request for assisted dying requires a certain kind of conversation with the patient, for which hospice might be well suited. Still, the relationship between assisted dying and hospice was also described by some as problematic, as they felt it obscured the public’s view of what hospice care entails:

I looked on the association page, and there’s all this advice about how to get information on Death with Dignity. I thought, if the public go straight (there), they’re going to think all we do is Death with Dignity and they’re not going to avail themselves with hospice. Because already there is an attitude among many of our clients that ‘if I go into hospice, they’re going to kill me because that’s what a hospice does’ (Nurse 2).

Others expressed concern that palliative care was not given as much public attention as assisted dying, which distorted the reality on the ground in terms of the numbers opting for assisted dying versus those in receipt of palliative care:

Patients and the public don’t quite understand what hospice is, and they have no idea what palliative care is. I think the palliative care people are struggling so hard to get recognition that when this topic comes up, they feel like very few people choose (assisted dying)—why do we spend all this energy on this? (Physician 10).

Non-standardized protocols and varying policies

Some interviewees reported that they feared breeching institutional policies or becoming subject to litigation if they were present with a patient who chose to have an assisted death. As one interviewee explained, their institution allows staff to be present in the patient’s home but prohibits them from being in the same room at the time of ingestion. Moreover, while some hospice employees are permitted to offer guidance concerning the medication, they are prohibited from interfering with it. Only after ingestion can the employee return and assist with whatever the patient or family needs. This, as it was explained, can be a fine line to navigate. Another interviewee indicated that most patients express a wish to have a nurse present when they die, and that although this may be prohibited, most hospice nurses would want to be present:

It turns out that our nurses said ‘we are going to be present. We’re not going to leave’. It’s too weird to step out of the house or sit in the car and then come back and the person is asleep (Physician 10).

Concerns about medications and continuity of care

Interviewees in Oregon expressed an overarching concern about patients’ ability to access the lethal medications, once prescribed. Although some hospice physicians may prescribe the medications, pharmacies and individual pharmacists are not obligated to dispense them. Moreover, interviewees stated that the prescribed medications were in some cases ‘prohibitively expensive’ for their clients and not always easy to access or guaranteed to produce the intended outcome:

It’s much harder to get than it was (…). It’s very, very expensive and so they’ve been developing other drugs. Sometimes patients wake up and (it’s) more likely that the death is going to be prolonged, and then what do you do? (Professional 2).

Less expensive medications sometimes cause a much slower dying process. This might create situations where hospice professionals must deliberate on how to offer different types of care for their patient:

We felt it was our responsibility. ‘What are we going to do with the person?’ They’re not dying, they need 24 support, are we going to move them to the hospice house? They could die in transport and that would mess up the whole scenario for them. We could do homecare; we could try moving them to a nursing home (Physician 7).

For some interviewees, institutional policies restricting involvement in assisted dying presented issues around continuity of care. One physician described how it was ‘very awkward’ for all involved if a patient wanted to end their life in a hospice facility that had a policy prohibiting assisted dying in their institution:

Typically, what happens is they park across the street from the hospice house, take the medication and then the family drives them there and then they get admitted to the hospice house (Physician 9).

The implication here is that if the life-ending medication is ingested outside of an institution which prohibits the practice, the patient can subsequently be admitted and receive care. Hospice services and staff are inevitably involved, but their role remains unclear and conflicted.

Quebec

A contested relationship

At the time of the study, Quebec’s law on Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) had been in effect just over 3 years. MAiD in Quebec only allows a physician to administer lethal medication to eligible patients who voluntary request to bring about their own death (14). The practice has remained highly contested (33) and despite widespread public support for assisted dying across Canada (34) there is great opposition within the medical community in Quebec (35,36). The contentious character of MAiD was reflected in our sample; some provided assisted dying as part of their practice while others did not.

Legally, all physicians regardless of their area of work may evaluate and administer MAiD. In public institutions this can take place in palliative care units where they must report cases occurring on the premises (37). According to Quebec interviewees, most palliative care professionals choose to conscientiously object whenever a patient requests MAiD, resulting in outside physicians being ‘called in’ to perform the procedure. Interviewees suggested that in such cases, the palliative care team will continue to care for the patient, but that this may lead to tension. For some interviewees involved in palliative care, it was important to emphasize that the Quebec law explicitly separates assisted dying from palliative care. Consequently, some interviewees felt that there should not be any relationship between palliative care and assisted dying at all, and that they should be offered to patients as alternative options. From this viewpoint, assisted dying was incompatible with the ethos and practical philosophy of palliative care:

There’s always something to be done. We are caring for the living ‘til their last breath, we’re not caring for the dying (…). Palliative care is guided by one ethical principle, which is, do not harm, and protect (Physician 12).

Several interviewees described palliative care as a particular environment, wherein the inclusion of assisted dying would be detrimental. For example, in the case of a patient receiving palliative care who requests MAiD:

From the moment a patient makes this request, he has no other aims. They don’t live the present moment (…). I felt that there was no place for care anymore. The need of care had disappeared, because there was a request for medically assisted death, and it would take up all the space (Physician 14).

Some interviewees strongly believed that assisted dying was eroding palliative care through a siphoning of funds, associated cultural changes, and a devaluation of palliative care professionals who, it was suggested, were increasingly leaving the field:

In my opinion, there will no longer be palliative care in 25 years. Because of pro-euthanasia movements. Because the fact of being able to solve in 5 minutes the suffering (…). It’s the easy way, and at the same time the economical way (Physician 17).

Interviewees who provided MAiD, however, outlined a different scenario:

I do palliative care and MAiD is just one aspect of the care that can be given to palliative care patients if they ask for it (Physician 15).

Some physicians who provided MAiD considered it and palliative care as separate interventions; yet performing the former was experienced as defending the patient’s choices and allowing them to die on their own terms. MAiD was viewed as a way of assuring open conversations, and dealing effectively with suffering, which was expressed in terms conveying a strong sense of beneficence:

A person who has asked for (MAiD) is telling you he can’t go on, he’s telling you he feels awful, he’s telling you (…) he just can’t do it anymore. It’s a cry for help, so to me that’s an emergency. It means that it’s an emergency to sit down with his people see what’s going on, and if you can’t give medical aid in dying, what can you do? Because there’s always something you can do. Whatever we’ve been doing up to now, it isn’t working anymore (Physician 19).

For the Quebec physicians who performed assisted dying, therefore, there was no inherent contradiction between palliative care and assisted dying.

The special character of independent hospices

Quebec has a number of freestanding hospices (38) with a special status due to funding sources that allows each hospice to decide independently whether or not to practice MAiD. According to interviewees, the majority of hospices currently do not allow MAiD. One interviewee reported that a hospice had changed its policy twice about whether or not to provide MAiD, leading to confusion and discontent among both professionals and patients. Another physician working in a hospice explained that while MAiD is not provided on site, the patient evaluation can occur there before the patient is transferred elsewhere for the procedure. This approach, according to the interviewee, has been subject to criticism. Some interviewees expressed that members of the public are cynical about the tactic of putting obstacles in a patient’s way or that it is undignified to submit dying patients to last minute hospital transfers in order to undergo MAiD, not least because the quality of the surroundings is typically better in hospice than in public hospitals.

Lack of knowledge about and access to palliative care

Interviewees in Quebec reported that the public’s lack of knowledge about and access to palliative care services is a great problem, which affects the relationship with assisted dying. Interviewees recounted instances of patients and families requesting MAiD because of insufficient symptom relief and care. It was mentioned that physicians were sometimes reluctant to abandon aggressive, curative approaches and to administer pain relief:

It’s crazy because we’ve been giving palliative care for years but people still don’t know much about it. Even nurses don’t dare talk about palliative care, for fear of hurting the patients (…). The day when we really have a free and informed choice, when we really have available and quality palliative care everywhere in Quebec, I will review the question of physician-assisted dying (Physician 14).

One physician described patients who had significant physical suffering who were unable to access specialist palliative care but were able to access MAiD:

She ended up walking into the clinic and they said that it was wonderful that she got her wish. I’m saying it’s too bad that she didn’t get better care and more support (Physician 13).

Discussion

This study was a response to calls within the literature to better understand the relationship of assisted dying with and impact on palliative care (39). The results demonstrate that this relationship is evolving in complex and sometimes localized ways in jurisdictions where assisted dying has become lawful. For some of the professionals we interviewed, assisted dying and palliative care represented opposing goals, a position which has been consistently represented in the palliative care literature (40,41) and within advocacy circles (42). For others in our study, both fields of practice correspond to a philosophy of care that fundamentally seeks alleviation of suffering and being present with patients (43).

Across all three jurisdictions, interviewees expressed some ambivalence about how the practice of assisted dying interacts with palliative care delivery. This appeared most divisive and contested in Quebec, perhaps because MAiD had only been lawful for 3 years at the time of our study, compared with nearly two decades in Flanders and over two decades in Oregon. The Quebec law designates palliative care and assisted dying as alternative options for patients and it seems many in palliative care currently wish to distance themselves from its use. However, there was not universal rejection of assisted dying among Quebec interviewees. For some, there was no necessary opposition between palliative care and assisted dying, and it was suggested instead that the latter is merely another way of being with patients suffering at end of life, and honoring their autonomy. In Flanders, euthanasia was not viewed as the exclusive preserve of palliative care, but rather it was the length and quality of the doctor-patient relationship which was deemed to be the most significant factor in determining which clinician should be involved and supported evidence that it reduces medical paternalism (44). In Flanders, assisted dying was not perceived to be necessarily incompatible with palliative care values, however, there were concerns expressed about it becoming normative, available ‘on demand’, and about an emerging ‘euthanasia positive’ culture.

In Oregon, differences in institutional policies and regulations mean that engagement with assisted dying varies from complete non-involvement to actively supporting the patient throughout every stage of the process (45). Similarly in Quebec, all public healthcare institutions are obligated to pursue requests for MAiD and provide care throughout the process (14), forcing a certain level of cooperation, whereas the province’s freestanding hospices are free to set their own policies (46). Our interviews indicated that differing institutional policies seemed to cause unease and even confusion amongst professionals. There was concern about restrictions placed on providing services for patients who avail themselves of assisted dying, which was considered to go against a core tenet of palliative care: caregiver presence and non-abandonment of patients (47). In Oregon specifically, there were also concerns expressed about patients’ ability to procure the prescribed medications, as noted elsewhere in the literature from the United States (48).

Regardless of palliative care professionals’ passionately held views on the ethics of legalization, once assisted dying is made lawful, professionals are compelled to respond and adapt their practices. Our interview data demonstrates that despite the resistance of some palliative care professionals to be involved, some level of relationship is inevitable once legislation has passed. The question then becomes about the guidance given to these professionals and the support they are offered by the institutions.

Limitations

Our study is the first to directly investigate the relationship between palliative care and assisted dying, as it is experienced and perceived by professionals in different locations. It is limited however, by the small number of participants who were interviewed in each location. We recognize that those who agreed may have had particular motivations to be interviewed and may not reflect the full range of available perspectives. Finally, each region studied is culturally distinct from the larger country that they are a part of. Results from another area of each country might be different.

Conclusions

We find that no clear or uniform relationship between palliative care and assisted dying can be identified in any of the three locations. Indeed, our analysis indicates that when a field of practice such as palliative care is potentially seen as threatened by another field, such as assisted dying, several patterns emerge that go beyond simple characterization of the relationship between the two. The relationship between assisted dying and palliative care is influenced by legal regulations that are subject to change (49,50), variable and sometimes inconsistent institutional policies and support systems, the type of assisted dying offered (medically or self-administered), and structures of healthcare funding (51). Cooperation or integration between the two practices may also be perceived by some as dependent upon whether palliative care professionals’ views of assisted dying are compatible with their views about ‘care’.

An overarching concern which unites the three jurisdictions is a lack of public knowledge, recognition and understanding of appropriate palliative care, as well as obtaining access to it. The context and practicalities of how assisted dying is being implemented alongside access to palliative care need to be attended to in order to inform any future laws. We seek a better understanding of whether and in what ways assisted dying presents a threat to palliative care. There is a clear need for more attention to how palliative care and assisted dying can co-exist, where both are available.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank each of the individuals who agreed to be interviewed for this study.

Funding: This work was supported by an Investigator Award to David Clark (grant number 103319) from the Wellcome Trust, London, United Kingdom.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Nancy Preston, Sheri Mila Gerson) for the series “Hastened Death” published in Annals of Palliative Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-632

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-632). The series “Hastened Death” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. SMG served as the unpaid Guest Editor of the series. DC reported grants from Wellcome Trust, during the conduct of the study. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was approved by the College Research Ethics Committee of the University of Glasgow, College of Social Sciences (Application No. 400180010). Written informed consent was obtained from the interviewees for publication of this study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

References

- Kissane DW, Street A, Nitschke P. Seven deaths in Darwin: case studies under the Rights of the Terminally III Act, Northern Territory, Australia. Lancet 1998;352:1097-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, et al. Attitudes and practices of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. JAMA 2016;316:79-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- . We risk our careers if we discuss assisted dying, say UK palliative care consultants. BMJ 2019;365:l1494. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. 2012. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- Inbadas H, Zaman S, Whitelaw S, et al. Declarations on euthanasia and assisted dying. Death Stud 2017;41:574-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gerson SM, Koksvik GH, Richards N, et al. The relationship of palliative care with assisted dying where assisted dying is lawful: a systematic scoping review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;59:1287-303.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finlay IG, Wheatley VJ, Izdebski C. The house of lords select committee on the assisted dying for the terminally ill bill: implications for specialist palliative care. Palliat Med 2005;19:444-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karsoho H, Wright DK, Macdonald ME, et al. Constructing physician-assisted dying: the politics of evidence from permissive jurisdictions in Carter v. Canada. Mortality 2017;22:45-59. [Crossref]

- Broeckaert B. Belgium: towards a legal recognition of euthanasia. Eur J Health Law 2001;8:95-107. [Crossref]

- Byock IR. Consciously walking the fine line: thoughts on a hospice response to assisted suicide and euthanasia. J Palliat Care 1993;9:25-8. [PubMed]

World Population Review 2019 . Available online: https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries- Oregon Legislature. The Oregon Death with Dignity Act, 127.800. 1994. Available online: https://www.oregonlegislature.gov/bills_laws/ors/ors127.html

- The Belgian Act on Euthanasia of May. 28th 2002. Ethical Perspect 2002;9:182-8. [PubMed]

- Gouvernement du Quebec. Medical aid in dying: Legal framework and description. 2019. Available online: https://www.quebec.ca/en/health/health-system-and-services/end-of-life-care/medical-aid-in-dying/

- Clark D, Baur N, Clelland D, et al. Mapping Levels of Palliative Care Development in 198 Countries: The Situation in 2017. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;59:794-807.e4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Population Review. Available online: http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/belgium-population/ (Accessed 8 October 2019).

- Economist Intelligence Unit. The 2015 Quality of Death Index: Ranking palliative care across the world. Econ 2015:71.

- Lynch T, Connor S, Clark D. Mapping levels of palliative care development: a global update. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:1094-106. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Overview of healthcare in Belgium. Available online: https://www.expatica.com/be/healthcare/healthcare-basics/the-belgian-healthcare-system-100097/ (Accessed 24 June 2020).

- Moreels S, Boffin N, Van den Block L, et al. Trends in palliative care at the end of life in Belgium, 2005-2014: Nicole Boffin. Eur J Public Health 2016;26:ckw174. 011.

- Lewis P, Black I. Adherence to the request criterion in jurisdictions where assisted dying is lawful? A review of the criteria and evidence in the Netherlands, Belgium, Oregon, and Switzerland. J Law Med Ethics 2013;41:885-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- OregonHealthcare.gov. Connecting Oregonians to health coverage. Available online: https://healthcare.oregon.gov/Pages/types-of-coverage.aspx (Accessed 24 June 2020).

- Oregon Health Authority. Oregon Revised Statute: Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act. Available online: https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PROVIDERPARTNERRESOURCES/EVALUATIONRESEARCH/DEATHWITHDIGNITYACT/Pages/ors.aspx (Accessed 24 June 2020).

- QUÉBECFIRST. Universal and free healthcare system. Available online: https://www.quebecentete.com/en/living-in-quebec-city/healthcare/ (Accessed 24 June 2020).

- Vaismoradi M, Jones J, Turunen H, et al. Theme development in qualitative content analysis and thematic analysis. J Nurse Educ Prac 2016;6:100-10. [Crossref]

- Terry G, Hayfield N, Clarke V, et al. Thematic analysis. In: Willig C, Stainton-Rogers W. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology. 2nd ed. London: SAGE, 2017:17-37.

- QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo 12. 12th ed. 2019.

- Chambaere K, Vander Stichele R, Mortier F, et al. Recent trends in euthanasia and other end-of-life practices in Belgium. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1179-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bernheim JL, Distelmans W, Mullie A, et al. Questions and answers on the Belgian model of integral end-of-life care: Experiment? Prototype?: 'Eu-euthanasia': The close historical, and evidently synergistic, relationship between palliative care and euthanasia in Belgium: An interview with a doctor involved in the early development of both and two of his successors. J Bioeth Inq 2014;11:507-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bernheim JL, Deschepper R, Distelmans W, et al. Development of palliative care and legalisation of euthanasia: antagonism or synergy? BMJ 2008;336:864-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- LEIF. Levens Einde Informatie Forum. 2020. [cited 2020 28 February 2020]. Available online: https://leif.be/home/

- Oregon Health Authority. Oregon Death with Dignity Act: 2018 Data Summary. 2018. Available online: https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PROVIDERPARTNERRESOURCES/EVALUATIONRESEARCH/DEATHWITHDIGNITYACT/Documents/year21.pdf

- Frazee C, Chochinov HM. The Annals of Medical Assistance in Dying. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:731-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- CBC News. Doctor-assisted suicide supported by majority of Canadians in new poll Oct 08, 2014. [10 March 2020]. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/health/doctor-assisted-suicide-supported-by-majority-of-canadians-in-new-poll-1.2792762

- Bouthillier ME, Opatrny L. A qualitative study of physicians’ conscientious objections to medical aid in dying. Palliat Med 2019;33:1212-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maclure J. Conscientious Objection to Medical Assistance in Dying: A Qualitative Study with Quebec Physicians. Can J Bioethics 2019;2:110-34.

- Commission sur les soins de fin de vie. Rapport sur La Situation Des Soins De Fin De Vie Au Québec. 2019.

- Canadian Virtual Hospice. Residential Hospices. 2020. Available online: http://www.virtualhospice.ca/en_US/Main+Site+Navigation/Home/Support/Resources/Programs+and+Services/Provincial/Quebec/Residential+hospices.aspx#id_0c7e864fce5db0cab6a4eaf6d340c613

- Dierickx S, Cohen J. Medical assistance in dying: research directions. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019;9:370-2. [PubMed]

- Finlay I. Dying and choosing. Lancet 2009;373:1840-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saunders DC. From the UK. Palliat Med 2003;17:102-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Inbadas H, Carrasco JM, Clark D. Representations of palliative care, euthanasia and assisted dying within advocacy declarations. Mortality (Abingdon) 2019;25:138-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hurst SA, Mauron A. The ethics of palliative care and euthanasia: exploring common values. Palliat Med 2006;20:107-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lewis D. What is the experience of assisted dying for Dutch healthcare staff working in a hospice or chronic disease care centre? Lancaster: Lancaster University, 2018.

- Campbell CS, Cox JC. Hospice-assisted death? A study of Oregon hospices on death with dignity. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012;29:227-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pesut B, Thorne S, Schiller CJ, et al. The rocks and hard places of MAiD: a qualitative study of nursing practice in the context of legislated assisted death. BMC Nurs 2020;19:12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Giordano J. Hospice, palliative care, and pain medicine: meeting the obligations of non-abandonment and preserving the personal dignity of terminally III patients. Del Med J 2006;78:419. [PubMed]

- Offord C. Accessing Drugs for Medical Aid-in-Dying. 2017 [August 16, 2017]. Available online: https://www.the-scientist.com/bio-business/accessing-drugs-for-medical-aid-in-dying-31067 (Accessed 24 June 2020).

- Dierickx S, Deliens L, Cohen J, et al. Euthanasia for people with psychiatric disorders or dementia in Belgium: analysis of officially reported cases. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17:203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Global News Staff. Quebec will comply with ruling that struck down assisted death provisions. 2020 January 21.

- Assisted Suicide Funding Restriction Act of 1997. 1997.