Sintilimab as salvage treatment in an HIV patient with relapsed/refractory Hodgkin: a case report

Introduction

Although classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) is usually curable with the traditional treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation, but unfortunately, a few patients will eventually develop to relapsed or refractory cases. There many ways to deal with this situation including second-line chemotherapy, autologous stem cell transplantation, monoclonal anti-CD30 antibody and immune checkpoint inhibitor such as anti-PD-1 drug, etc. Nowadays, anti-PD-1 drug isn’t only used in cHL, but also widely applicated in many solid cancers such as non-small cell lung cancer. Sintilimab (Innovent Biologics, Suzhou, China) is a highly selective, humanized, monoclonal antibody that blocks the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands. As an anti-PD-1 drug, Sintilimab has improved the outcome of patients with relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (R/R cHL) in a multicentre, single-arm phase II trial, but to R/R HIV-cHL patients, no any case treated with Sintilimab was reported although a few cases were reported with the similar drugs such as Nivolumab.

We present the following case in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1333).

Case presentation

A 31-year-old Chinese man with R/R HIV-cHL has successfully reached complete remission after nine cycles of the PD-1 blockade Sintilimab Injection treatment.

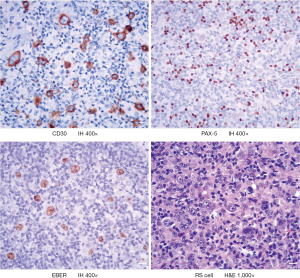

The patient found himself enlarged lymph nodes in both side cervix in April 2018, without fever, night sweat, and weight loss. He was diagnosed with AIDS in March 2015 and has taken oral anti-retrovirus treatment regularly since then, and his status was under control with undetectable viral load and AIDS-related symptoms. After biopsy and pathological examination in the local hospital, the patient was diagnosed as lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin lymphoma (LRCHL), the HE shows: CD3−, CD30+, CD15−, PAX-5+ (weak), CD20+, EBER+, Ki67 30%, CD45-, CD79a−, MUM-1+, BCL2− (Figure 1). PET-CT examinations showed multiple enlarged lymph nodes in the bilateral neck, submandibular, clavicle, double axilla, mediastinum, right hila, abdominal cavity, retroperitoneum, and bilateral pelvic wall near iliac vessels and groin. Further, an elevated SUV and Splenomegaly with elevated SUV were observed. Other laboratory checks showed albumin 38.75 g/dL; hemoglobin 10.9 g/dL; white blood cell count 3,770.0/mm3; lymphocyte count 980/mm3. Finally, this patient was diagnosed as HIV-LRCHL IIIE+S.

From May 2018, we began to give the patient chemotherapy, he received the combination of ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine) regime for six cycles and prophylactic intrathecal (IT) treatment(methotrexate 15 mg every 4weeks, for total 4 times), all the courses went well, and no more than II grade toxicities happened. In January 2019, the patient finished the treatment and received a PET-CT check again, the results showed the sizes of all the enlarged lymph nodes reduced to normal, and Deauville scored less than 3, except residual lesions in bilateral pelvic walls near iliac vessels and groin with elevated SUV. All the residual lesions above were treated with radical radiation, and the treatment went well.

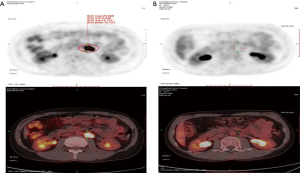

In April 2019, we evaluated efficacy six weeks after radiotherapy. The PET-CT shows an enlarged lymph node with an elevated SUV in the left hila. The patient refused an auto stem cell transplant. Then we gave the patient the second line GDP (gemcitabine, dexamethasone, and cisplatin) regime chemotherapy. Unfortunately, after five cycles of treatment, in September 2019, PET-CT examination found new emerging enlargement lymph node in the retroperitoneum and with elevated SUV. However, other lesions disappeared (Figure 2A).

In October 2019, the patient aggressed to PD-1 immune checkpoint treatment. The Sintilimab Injection has prescribed 200 mg ever 3 weeks, all the courses of treatment went through smoothly and no III–IV grade toxicity, after 9 cycles of treatment, we evaluated the effect of treatment, PET-CT showed that the new emerging enlargement lymph node found last time in the retroperitoneum has disappeared completely (Figure 2B).

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this study and any accompanying images.

Discussion

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is an uncommon malignancy involving lymph nodes and the lymphatic system and is divided into two main types, according to the WHO classification: cHL and nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL). Furthermore, cHL includes four subtypes: nodular sclerosis cHL; mixed cellularity cHL; lymphocyte-depleted cHL; and lymphocyte-rich cHL (1)

Studies have shown that human immunodeficiency virus infection increases the risk of tumorigenesis and that patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome are 100 times more likely to develop lymphoma than the general population (2,3). The most common subtypes of NHL in people living with HIV are diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), Burkitt lymphoma (BL), and primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL), and the incidences of HL are also elevated in HIV positive patients but is much less common than BL or DLBCL (4). Although HIV-positive HL is not AIDS-defined cancer, the risk of HL in HIV-positive individuals is 10–20 times that of the general population (5). But the reason for Hodgkin lymphomagenesis in the HIV infected population is not clear, some studies show EBV could be detected in almost all HIV-HL patients, comparing that in HIV-negative ones (6). As we know, the 9p24.1 locus contains the genes encoding programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 and 2 (PD-L1 and PD-L2), and JAK2; lymphoma-associated aberrations in this locus result in increased expression of these proteins, and the EBV-latent membrane protein (LMP1) may induce PD-L1 expression via the AP-1 and JAK-STAT pathways in cHL cells with diploid 9p24.1 (7,8).

Compared to the HIV-negative patients, HIV patients with lymphoma tend to have more B-symptoms at presentation, greater extra-nodal involvement, increased likelihood of bone marrow disease, and poorer performance status. The histology types of mixed cellularity or lymphocyte-depleted in classical HL companied with Human immunodeficiency virus are more common, and the HIV-cHL is almost universally Epstein-Barr virus-positive (6). In the pre-combined antiretroviral therapy (cART) era, HIV-cHL prognosis was dismal due to the aggressiveness of the lymphoma and the poor prognosis of the HIV infection (9). With the widespread use of antiretroviral therapy, the overall incidence of HIV-associated Kaposi sarcoma, primary central nervous system lymphoma, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma have been decreasing rapidly, but the incidence of HIV-cHL has not significantly decreased (10). With CARTs advent, although the incidence of CHL has increased, the response to treatment and long-term survival has also improved (11). Some studies have proved that HIV-positive patients with cHL had more aggressive baseline features. However, there were no differences in response rate or survival between HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients, not significantly associated with higher mortality in HIV-positive patients (12,13).

Even the advancement of HIV-cHL prognosis, there are still a few patients that can get complete remission and eventually come into R/R HIV-cHL, so the salvage treatments are challenging. Studies are finding a high proportion of cHL tumor harboring cells expressing PD-1 ligands, which has provided the rationale for clinical trials of inhibitors of this immune checkpoint (7).

There many ways to deal with R/R HIV-cHL including second-line chemotherapy, autologous stem cell transplantation, monoclonal anti-CD30 antibody and immune checkpoint inhibitor, etc. Immune checkpoint blockade emerged as an essential treatment option for patients with relapsed or refractory HL in 2015 after a pivotal single-arm multicenter trial of nivolumab monotherapy demonstrated an impressive objective response rate of 87% with mild toxicities (14,15). Another prospective treatment is CD30-specific CAR-T, but there are only a few clinical trials having been reported. In a phase I clinical trial with R/R HL and Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (ALCL) showed that CD30-specific CAR-Ts are safe, indicating that further assessment of this therapy is warranted (16). Nowadays, there is no any evidences whether anti-PD-1 drugs is useful for HIV or not, some experts think anti-PD-1 therapy holding promise as adjunctive therapy for chronic infectious diseases such as TB and HIV, but need to be tested in randomized clinical trials (17,18). However, to HIV-cHL, only three cases had been reported with the treatment of PD-1 immune checkpoint, all the three cases had positive outcomes, and one of them reached complete remission (CR) (6,15,19). In our case, the young patient had experienced two regimes of chemotherapy and radiation for 17 months and finally progressed. After we gave him Sintilimab Injection treatment for 9 cycles, he reached complete remission, with our knowledge, this is first reported in Asia and the second CR case in the world.

Sintilimab is effective in R/R HIV-cHL, and the toxicities are accepted, further prospective clinical trials to verify are valuable.

The patient now has no any symptoms, and can do some housework now. He is willing to continue this treatment.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Sponsored by Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China (cstc2019jcyj-msxmX0793).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1333

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-1333). The authors report grants from Natural Science Foundation of Chongqing, China, during the conduct of the study.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this study and any accompanying images.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Sabattini E, Bacci F, Sagramoso C, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues in 2008: an overview. Pathologica 2010;102:83-7. [PubMed]

- Goedert JJ. The epidemiology of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome malignancies. Semin Oncol 2000;27:390-401. [PubMed]

- Beral V, Peterman T, Berkelman R, et al. AIDS-associated non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet 1991;337:805-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gopal S, Patel MR, Yanik EL, et al. Temporal trends in presentation and survival for HIV-associated lymphoma in the antiretroviral therapy era. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013;105:1221-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Castillo JJ, Bower M, Brühlmann J, et al. Prognostic factors for advanced-stage human immunodeficiency virus-associated classical Hodgkin lymphoma treated with doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine plus combined antiretroviral therapy: a multi-institutional retrospective study. Cancer 2015;121:423-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thompson LD, Fisher SI, Chu WS, et al. HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 45 cases. Am J Clin Pathol 2004;121:727-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goodman A, Patel SP, Kurzrock R. PD-1-PD-L1 immune-checkpoint blockade in B-cell lymphomas. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017;14:203-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Green MR, Rodig S, Juszczynski P, et al. Constitutive AP-1 activity and EBV infection induce PD-L1 in Hodgkin lymphomas and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders: implications for targeted therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:1611-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levine AM, Li P, Cheung T, et al. Chemotherapy consisting of doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine with granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor in HIV-infected patients with newly diagnosed Hodgkin's disease: a prospective, multi-institutional AIDS clinical trials group study (ACTG 149). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2000;24:444-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Ramírez RU, Shiels MS, Dubrow R, et al. Cancer risk in HIV-infected people in the USA from 1996 to 2012: a population-based, registry-linkage study. Lancet HIV 2017;4:e495-504. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Besson C, Lancar R, Prevot S, et al. High Risk Features Contrast With Favorable Outcomes in HIV-associated Hodgkin Lymphoma in the Modern cART Era, ANRS CO16 LYMPHOVIR Cohort. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61:1469-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sorigué M, García O, Tapia G, et al. HIV-infection has no prognostic impact on advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma. AIDS 2017;31:1445-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Olszewski AJ, Castillo JJ. Outcomes of HIV-associated Hodgkin lymphoma in the era of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2016;30:787-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2015;372:311-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang E, Rivero G, Patel NR, et al. HIV-related Refractory Hodgkin Lymphoma: A Case Report of Complete Response to Nivolumab. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2018;18:e143-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramos CA, Ballard B, Zhang H, et al. Clinical and immunological responses after CD30-specific chimeric antigen receptor–redirected lymphocytes. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:3462-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Filaci G, Fenoglio D, Taramasso L, et al. Rationale for an Association Between PD1 Checkpoint Inhibition and Therapeutic Vaccination Against HIV. Front Immunol 2018;9:2447. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rao M, Valentini D, Dodoo E, et al. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy for infectious diseases: learning from the cancer paradigm. Int J Infect Dis 2017;56:221-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sandoval-Sus JD, Mogollon-Duffo F, Patel A, et al. Nivolumab as salvage treatment in a patient with HIV-related relapsed/refractory Hodgkin lymphoma and liver failure with encephalopathy. J Immunother Cancer 2017;5:49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(English Language Editor: J. Chapnick)