Palliative care needs in Parkinson’s disease: focus on anticipatory grief in family carers

Introduction

The psychological impact of Parkinson’s disease (PD) on the person diagnosed, and on their family, is enormous. A diagnosis of PD can have a negative effect on spousal and family relationships, and the progressive nature of the illness places an increasingly heavy burden on carers, who often experience psychological and emotional stress. It is increasingly recognized that people with PD and their families would benefit from a palliative care approach which addresses these complex needs (1,2).

Although many healthcare professionals expect fear and stigma about palliative care from people with PD and their families (3), there is some evidence that people with PD and their families are simply unfamiliar with the concept, and that when the supportive role of palliative care is explained to them, they would welcome this support as they would welcome any support to improve their quality of life (4,5).

In our previous paper (4) we explored the perspectives of people with PD and family carers on palliative care, through in-depth qualitative interviews with 19 people with PD and 12 carers. We uncovered multiple palliative care needs faced by carers which we could only briefly present in the paper owing to space limitations, however we noted that “the bereavement process may start before the PwPD’s death as carers grieve the loss to a nursing home or loss of their loved one’s personality”. Carers described multiple losses while living with their loved one’s disease. Personality changes were discussed which were indirectly or directly linked to the PD, for example depression and social withdrawal in response to the diagnosis, or the development of impulsive behaviors. Other carers grieved for their past relationship, before being forced into the role of “carer”; or their previous life, before travelling and holidays became unmanageable. Carers of people with PD in general reported being unprepared for advanced illness and their partner’s high support needs towards end-of-life and described the depression and upset they experienced at each new loss. Such experiences appeared to be typical of “anticipatory grief”, a concept more widely studied in relation to cancer and dementia. We argued that a palliative care approach which includes the family could help to address these complex psychological needs. It appeared that a better understanding of the concept of anticipatory grief, as experienced by PD carers, would be essential to formulating a palliative care model that encompasses all needs.

The concept of anticipatory grief is becoming more widely studied and better understood in relation to a number of diseases. It is sometimes used interchangeably with other terms in the literature including pre-death grief, or preparatory grief. Anticipatory grief can occur in response to numerous losses, loss of personal freedom, changes in roles, worry about the future, loss of relationship, loss of aspects of personality (6). Anticipatory grief can be experienced by a person faced with a life-limiting illness, or their loved ones. When compared with grief after death, anticipatory grief has been associated with higher intensities of anger, loss of emotional control, and atypical grief (7); importantly, anticipatory grief doesn’t necessarily lessen post-death bereavement (8).

A small body of research has measured anticipatory grief in people with PD and carers previously. Kluger et al. (1) surveyed 90 people with PD regarding various palliative care needs. Grief, as measured by the prolonged grief questionnaire, was common, was experienced across the disease stages, and was an independent predictor of health-related quality-of-life, even after controlling for depression and motor disease severity.

Carter et al. (9) used the Marwit and Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory-Short Form (MMCGI-SF) to explore grief among current PD carers; 17% were experiencing grief one standard deviation (SD) above the mean of the group as a whole. Furthermore, variance in grief scores was more associated with non-motor symptoms than by motor symptoms. Johansson and Grimby (10) used the Anticipatory Grief Scale (AGS) to investigate anticipatory grief among family members of people with PD. Carers expressed their longing for their life pre-illness and anger at the unfairness of the situation. Cognitive changes and communication difficulties were particularly associated with increased scores on the AGS, as emotional closeness between the family carer and the person with PD was affected.

Anticipatory grief has thus far been more widely studied in relation to cancer (11,12) and outside of cancer, in dementia. The literature suggests that the experience is comparable for carers of people with PD and those with dementia (10,13,14). The cognitive functioning of the patient seems to be a particularly important predictor of anticipatory grief, which helps explain observed similarities. Investigations of anticipatory grief in cancer (using the AGS and interviews) showed similar patterns of symptoms such as significant emotional stress, as intense preoccupation with the dying, longing for his/her former personality, loneliness, tearfulness, cognitive dysfunction, irritability, anger and social withdrawal, and a need to talk (11).

Based on qualitative studies with carers of people with PD, it appears that anticipatory grief may be a key symptom to be addressed in an inclusive palliative care framework for PD. The present study sought to add to the literature by exploring this phenomenon using the “AGS”. The specific aims were:

- To demonstrate the occurrence of anticipatory grief experienced by caregivers of people with PD;

- To explore how this grief relates to caregiver and depression, and to demographic and illness-related variables;

- To add to the characterization of the concept of anticipatory grief through discussion of these relationships.

Methods

Participants and data collection

Carers of people with PD were recruited from two movement disorder clinics in Cork city, Ireland (one neurologist-provided and one geriatrician-provided clinic), using convenience sampling methodology. A carer was defined as any family member who provides unpaid/informal care and support to the person with PD; they did not have to be the “primary” carer. A researcher attended the clinics, and a senior clinic nurse identified carers who fitted the inclusion criteria based on the patient charts. She further identified people who met the exclusion criteria, i.e., receipt of poor prognosis/bad news on the day, or other ongoing serious medical, social, or psychological events that made this study in-opportune for them. The researcher approached suitable carers in the waiting room with oral and written information about the study. Those who expressed an interest were given the opportunity to take part immediately, completing the survey in a private room with or without the researcher assisting, or to take the survey pack home, with pre-paid postal return. The inclusion criterion was: caring for someone with PD who was at Hoehn & Yahr stage 3–5 (i.e., bilateral disease with postural instability but still physically independent, through to wheelchair bound or bedridden unless aided). The exclusion criteria were: a new referral to the service (inappropriate to recruit to an emotionally sensitive research study); non-English speaker. The survey process (i.e., demographic and background questions, and three surveys) took between 20–30 minutes to complete.

Measures

The AGS

The AGS [Theut et al. (6)] was used to measure anticipatory grief. This is a 27-item self-administered questionnaire assessing reactions to and coping with expected death. The responses range from “Strongly disagree”, “Disagree”, “Somewhat agree, “Agree”, and “Strongly agree”. The scale typically takes about 10–15 minutes to complete. The AGS scale represents the major domains cited in the literature on grief. It was developed for use in carers of people with dementia, but has been adapted to assess populations including cancer and PD (10). Internal consistency is good (Cronbach’s alpha =0.84).

Zarit Burden Index

Subjective carer burden was measured using the 12-item version of the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) (15). This shortened version correlates well with the original 21- and 22-item versions. A standard cut-off point of 17 (15) indicates “high burden”. The maximum score is 48. The 12-item ZBI has high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha =0.87).

Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)

The 15-item version of the GDS was used to assess depression. Questions are answered “yes” or “no” and the maximum score is 15. Although the GDS is a screening rather than a diagnostic or severity-rating tool, scores of 0–4 are considered normal; 5–8 indicate mild depression; 9–11 indicate moderate depression; and 12–15 indicate severe depression. The GDS takes about 5 minutes to complete. Internal consistency is good, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.81 reported (16). The GDS has been used in research with younger adult carers to assess depressive symptoms (17), being recently validated for use in young and middle-aged adults (18).

Demographic and PD status variables

These were measured using a survey specifically created for this study (see Table 1 for variables). Variables included the person with PD and carer’s gender, age, relationship and living situation; the person with PD’s disease stage (survey questions based on the Hoehn & Yahr scale) and duration, as well as their mobility, level of assistance required with activities of daily living (ADLs) (questions based on Barthel Index items), and any behavioural or cognitive problems (questions based on carer-rated frequency of behaviour). Also recorded were: the carer’s rating of the person with PD’s current health and the quality of the health and social care received by the person with PD (5-point Liekhart scales); the carer’s perception of whether they or their loved one was depressed (yes/no/maybe options); the level of formal and informal support received, and whether caring had affected them financially.

Full table

Data analysis

Because of the exploratory nature of this study, we adopted a very conservative approach to these analyses. Data are mainly presented using descriptive statistics. The primary dependent variable of interest, the AGS, was normally distributed thus we used parametric inferential statistics (t-tests and one-way ANOVA) to tentatively investigate differences among levels of demographic variables reported. While multiple comparisons are made, the small sample size precluded a correction for multiple comparisons such as Bonferroni adjustments. Therefore, while interesting associations are highlighted in the results, these should be interpreted with caution, and considered mainly as notable discussion points to influence further research in larger samples.

Results

Sample demographics

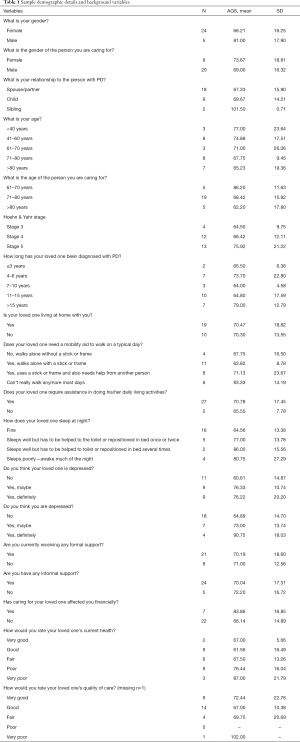

In total, 29 family carers agreed to complete the survey, and all commenced surveys were completed. Sample demographics are shown in Table 1, and descriptive data is presented for all background variables.

Nature and level of anticipatory grief experienced

Noting that the scale range for the AGS is 27–135, the level of grief in the sample was high (mean =70.41; SD =16.93; sample range, 38–102). Responses for each AGS item are shown in Figure 1; the items most endorsed were “No one will ever take the place of my relative in my life” (mean =4.28, SD =1.22) and “I very much miss my relative the way she/he used to be” (mean =4.10, SD =1.26). In contrast, the items “I blame myself for my relative’s illness” (mean =1.07, SD =0.26) and “I don’t feel close to my relative who has PD” (mean =1.69, SD =1.04) were infrequently endorsed.

Patterns of association between anticipatory grief, caregiver burden, and caregiver depression

Scores on the AGS were most strongly correlated with scores on the ZBI (r=0.785, P<0.001), but also with the GDS (r=0.630, P<0.001). Scores on the ZBI and GDS were also correlated (r=0.724, P<0.001).

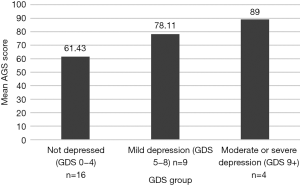

Dividing the sample into carers with high or low caregiver burden, using standard cut-off points, carers with higher care burden (n=18, mean =79.67, SD =12.67) had higher levels of anticipatory grief than those with lower care burden (n=11, mean =55.27, SD =11.12; t(27) =−5.26, P<0.001); see Figure 2. Similarly, carers experiencing higher depression scores also scored higher on the AGS; a one-way ANOVA revealed a statistically significant difference in AGS scores across three groups (using standard cut-offs for no depression (n=16, mean =61.43, SD =13.32), mild depression (n=9, mean =78.11, SD =13.59), and moderate to severe depression (combined due to small n; n=4, mean =89.00, SD =15.12); F(2,26) =8.63, P<0.001; see Figure 3). Post-hoc comparisons using Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) indicated a significant difference between the groups “not depressed” and “mild depression” (P=0.018), between “not depressed” and “moderate-severe depression” (P=0.003), however there was no significant difference between the groups “mild depression” and “moderate-severe depression” (P=0.392).

Patterns of association between anticipatory grief and demographic/disease variables

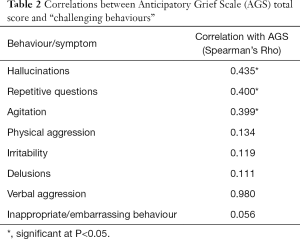

Mean AGS scores are displayed for each background variable in Table 1. Carers were asked to score how often their loved one displayed certain behaviours and these were correlated with scores on the AGS and the results are shown in Table 2. The variables significantly correlated with AGS scores were having hallucinations (rho =0.435, P<0.001), repetitive questioning (rho =0.400, P=0.017), and agitation (rho =0.399, P=0.016). The strength of these correlations is considered “moderate”.

Full table

Participants caring for a person with PD at Hoehn & Yahr stage 5 had higher anticipatory grief (n=13, mean =75.92, SD =21.22) than those caring for a person in earlier stages (n=16, mean =65.94, SD =11.28) although this difference was not statistically significant [t(27,17.41) =−1.53, P=0.144]. Similarly, participants caring for a person who had been diagnosed for a longer period (grouped as <7, 7–15, >15 years) experienced more anticipatory grief, although this also did not reach significance [F(2,26) =1.81, P=0.184]. Carers whose loved one needed assistance to walk had higher anticipatory grief (n=14, mean =76.36, SD =20.45) than those who could walk independently with or without a stick or frame (n=15, mean =64.87, SD =10.80), although this difference did not reach significance [t(27,19.43) =3.75, P=0.067]. Carers whose loved one did not sleep well had significantly higher anticipatory grief (n=11, mean =80.00, SD =18.32) than those who slept fine [n=18, mean =64.56, SD =13.38; t(27,16.55) =−2.62, P=0.027]. Carers who felt that their loved one was depressed (n=18, mean =76.28, SD =15.69) experienced significantly higher anticipatory grief themselves than those who did not feel their loved one was depressed [n=11, mean =60.81, SD =14.87; t(27,22.19) =−2.62, P=0.014]. Carers who felt that they were depressed also experienced significantly greater anticipatory grief (n=11, mean =79.45, SD =17.05) than those who did not feel depressed [n=18, mean =64.89, SD =14.70; t(27,18.85) =−2.44, P=0.030]. Those who were affected financially by caregiving experienced greater anticipatory grief (n=7, mean =83.86, SD =16.85) than those who were not affected financially [n=22, mean =66.14, SD =14.89; t(27,9.19) =−2.66, P=0.034].

Discussion

Anticipatory grief was commonly experienced by those caring for a family member with PD. Carers felt that no one could ever replace their loved one, and grieved for the person they used to be. Many expressed how “unfair” the illness was, were preoccupied with thoughts about their loved one’s illness and what life could have been if they were never diagnosed, and felt the need to talk to others regarding the experience. Similar patterns of response were observed by Johansson and Grimby (10). It is likely that these carers would have benefitted from increased emotional support from their healthcare team, such as counselling.

Anticipatory grief was strongly correlated with caregiver burden, but to a lesser degree with caregiver depression scores, whereas it may be intuitive that grief and depression would have more commonality in terms of phenomenology and hence scoring on tools measuring these constructs. It is intriguing to consider that a caregiver’s grief may have more to do with the caregiving needs of the person with PD than the affect of the caregiver. A previous study by Holley and Mast (14) of caregivers for a person with dementia found that anticipatory grief was independently associated with caregiver burden, beyond the effects of caregiver depressive symptoms. This study found the strongest correlation between caregiver burden and “personal sacrifice and burden” items in the MMCGI. The relationship between caregiver experiences of caregiving burden, depression and grief is likely to be multi-directional, such that, for example, grief and caregiver burden can lead to depressive symptoms; while depression can worsen feelings of grief and burden. It was not possible in this cross-sectional study to explore causality. Complicating things further, the tools have some overlap in their items, such as “Since the diagnosis of PD was made for my relative, I don’t feel interested in keeping up with the day to day activities” (AGS) and “Have you dropped many of your activities and interests?” (GDS), which may inflate correlations.

Anticipatory grief was more common among carers of a loved one with PD experiencing hallucinations, repetitive questioning, and agitation. Other literature has also found that cognitive decline and other non-motor symptoms (1,9) are particular risk factors for anticipatory grief in PD. The mean score in the current sample was similar to that reported previously for carers of people with dementia (mean =70.11; SD =14.78) (13), again suggesting commonalities in the caregiving experience between these two illnesses. As expected, more advanced disease stage was associated with higher carer anticipatory grief; this has also been observed among Alzheimer’s carers and shown to be independent of relationship status of caregiver to care recipient, caregiver age and self-rating of health, or location of care (17).

Other associations of note included greater anticipatory grief experienced among carers whose loved one was younger (and who therefore tended to be younger themselves). It is likely that older people have already experienced other illnesses and losses, or may have a certain expectation of ill health in themselves or their loved one, which may modulate their reaction to their loved one having a life-limiting diagnosis. Increasing levels of anticipatory grief, were furthermore associated with more limited mobility, difficulties sleeping and in performing ADLs. This is in keeping with the “multiple losses” associated with progressing PD being associated with grief while the person is still alive.

Interestingly, among the carers sampled, whether or not their loved one was living with them was not a factor in their level of anticipatory grief. Perhaps there are similar difficulties in living with the person and providing 24-hour care, and in arranging appointments and visits and the constant worry about someone who is not living with you. The relationships between anticipatory grief and levels of formal and informal support being received, and perception of quality of formal healthcare services were not as clearly defined, although the small numbers between subgroups makes it difficult to interpret. However, it may be that disease-related factors are more important to understanding grief than service-related factors. Being affected financially by caregiving however was related to increased expression of anticipatory grief.

It must equally be remembered that there are vast individual differences in response to stressors such as a loved one having a life-limiting illness, distressing symptoms, and assuming the role of caregiver. It is also noteworthy that not everyone in this sample was experiencing depression, grief, or burden. This may reflect personal resilience wherein some carers may adapt and cope better than others, or external factors such as family support. A conceptual model of protective factors against stress among PD carers has been put forth previously (19). Furthermore, carers can report positive aspects of caring and still experience grief, and not all grief is pathological.

This study has some limitations, mainly that it is not possible to make generalisations due to the convenience method of recruitment at two clinics in the same city, the small sample size, and the cross-sectional design. However, the study does highlight the occurrence of anticipatory grief among carers of people with middle stage and advanced PD, as a separate construct to caregiver burden and caregiver depressive symptoms. Future research using grief scales in PD populations will further illuminate these findings.

Conclusions

Palliative care is an approach which focuses on improving quality-of-life of people with life-limiting illness and their families by addressing their physical, psychological, social and spiritual needs. Many healthcare professionals do not feel knowledgeable about PD palliative care (2), and so require education in this area. It is clear that excellent bereavement care should be available to support families before and after a death. Clinicians should use the AGS or similar tools to identify and explore caregiver anticipatory grief, rather than solely focusing on caregiver burden, wherein the emotional aspects may be missed if the focus is just on “caregiving”. The authors believe that the assessment and treatment of anticipatory grief should form part of any model of palliative care for PD.

In conclusion, proper assessment and management of carers’ palliative care needs, including anticipatory grief, must occur regularly, and bereavement support must include the periods both before and after death.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study received approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Cork Teaching Hospitals [No. ecm6(v)01/03/16] and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

References

- Kluger BM, Shattuck J, Berk J, et al. Defining Palliative Care Needs in Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2018;6:125-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fox S, Gannon E, Cashell A, et al. Survey of Health Care Workers Suggests Unmet Palliative Care Needs in Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2015;2:142-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fox S, Cashell A, Kernohan WG, et al. Interviews with Irish healthcare workers from different disciplines about palliative care for people with Parkinson's disease: a definite role but uncertainty around terminology and timing. BMC Palliat Care 2016;15:15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fox S, Cashell A, Kernohan WG, et al. Palliative care for Parkinson's disease: Patient and carer's perspectives explored through qualitative interview. Palliat Med 2017;31:634-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boersma I, Jones J, Carter J, et al. Parkinson disease patients' perspectives on palliative care needs: What are they telling us? Neurol Clin Pract 2016;6:209-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Theut SK, Jordan L, Ross LA, et al. Caregiver's anticipatory grief in dementia: a pilot study. Int J Aging Hum Dev 1991;33:113-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilliland G, Fleming S. A comparison of spousal anticipatory grief and conventional grief. Death Stud 1998;22:541-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simon JL. Anticipatory grief: recognition and coping. J Palliat Med 2008;11:1280-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carter JH, Lyons KS, Lindauer A, et al. Pre-death grief in Parkinson's caregivers: a pilot survey-based study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18 Suppl 3:S15-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johansson UE, Grimby A. Anticipatory grief among close relatives of patients with Parkinson's disease. Psychology and Behavioral Sciences 2014;3:179-84. [Crossref]

- Johansson AK, Grimby A. Anticipatory grief among close relatives of patients in hospice and palliative wards. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2012;29:134-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng JO, Lo RS, Chan FM, et al. An exploration of anticipatory grief in advanced cancer patients. Psychooncology 2010;19:693-700. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garand L, Lingler JH, Deardorf KE, et al. Anticipatory grief in new family caregivers of persons with mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2012;26:159-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holley CK, Mast BT. The Impact of Anticipatory Grief on Caregiver Burden in Dementia Caregivers. Gerontologist 2009;49:388-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, et al. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist 2001;41:652-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Almeida OP, Almeida SA. Short versions of the geriatric depression scale: a study of their validity for the diagnosis of a major depressive episode according to ICD-10 and DSM-IV. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1999;14:858-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams KB, Sanders S. Alzheimer’s Caregiver Differences in Experience of Loss, Grief Reactions and Depressive Symptoms Across Stage of Disease: A Mixed-Method Analysis. Dementia 2004;3:195-210. [Crossref]

- Guerin JM, Copersino ML, Schretlen DJ. Clinical utility of the 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS-15) for use with young and middle-aged adults. J Affect Disord 2018;241:59-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greenwell K, Gray WK, van Wersch A. Predictors of the psychosocial impact of being a carer of people living with Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2015;21:1-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]