Loss of relationship: a qualitative study of families and healthcare providers after patient death and home-based palliative care ends

Introduction

A case

The following case illustrates the established relationship and subsequent loss between a homecare physician, patient, and the patient’s family in home palliative care. Dr. Paula Pallium is the palliative care doctor for George Adeno, a 76-year-old gentleman with metastatic lung cancer. Dr. Pallium makes regular visits to the home of Mr. Adeno, developing a warm relationship with the patient’s wife and grown children. Through frequent visits, trust and amity are built and her role becomes far more than a healthcare provider (HCP). She is often greeted with hugs and a cup of coffee and when Mr. Adeno is feeling well enough, they chat casually about cottage life and pet dogs. After 5 months of home palliative care Mr. Adeno dies peacefully at home. To express her condolences, Dr. Pallium sends a note to the family but visits and communication come to an abrupt halt. This loss of relationship is emotionally taxing for both Dr. Pallium and the Adeno family but they do not know what to do about it.

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as an approach aimed at enhancing the quality of life of patients and their families experiencing a life-threatening illness (1). In home-based palliative care the patient is cared for in their home, while doctors and other HCPs make visits as required. The family of the patient is heavily involved in the illness treatment and management, as well as providing affection and support (2,3). The doctor-patient relationship is of paramount significance in palliative care, as care goals transition when moving from curative to palliative care and a wider spectrum of needs are required to be met (4). Through provision of orientation, information, and support for family caregivers, a relationship between the doctor and the patient family is often fostered (5). A doctor-family partnership is a staple of home-based care and the place of the doctor in the home becomes well-established through the course of multiple visits. The doctor does not solely provide a support system for the patient, but undoubtedly for the family of the patient as well, especially near the end of the patient’s life (6). In a doctor-patient relationship, as described by Adler (in 2002) from a sociophysiological standpoint, social support effectuates relief and healing (7). Due to the robust family involvement in homecare, this benefit may extend to family members. Support from HCPs in palliative care invoke positive emotion and resilience in family members (8).

Upon death of the patient, there is an automatic yet challenging loss of connection between the HCP and the family of the patient. Compounded with this are the natural human feelings of intense grief and bereavement that arise from the loss of a loved one. Various studies have explained these emotions and how bereavement can potentially lead to adverse effects on health (6,9-13). Family members can be at risk for complicated grief and experience substantial distress and lack of healing (14). Morbidity and mortality may also be associated with bereavement (15). In palliative care specifically, anticipatory grief may also occur. This is a form of grief that takes place before the death of the patient, and may prompt behaviours of denial, guilt, anger, and seeking of reassurance (16). Since this type of grief occurs during the palliative care process, and hence when HCPs are still regularly visiting, families may seek comfort for these behaviours. Following the death of a patient, the family may remain in need of contact with the physician (6). Bedell et al. view it as the responsibility of the doctor to provide support to the bereaved family members, stating that care should not end immediately after the death of the patient (17). Additionally, family members of deceased patients often appreciate post-death follow-up with HCPs (8). Not only does the death cause immense grief to the family, but the doctors also struggle with this loss, as it is a disconnect of a reciprocal engagement.

In order to improve the quality of palliative care, there is a need for research involving bereaved family members (8,18,19). Although there are studies on bereavement (6,9-13) and the opinions and needs of family members regarding contact from physicians (patient’s physician, general practitioner) after patient death (6,9,17), no study has evaluated palliative care doctors’ views towards how maintaining contact with families may affect their experience with the loss of relationship. Additionally, there is no study evaluating loss of relationship in the light of home-based palliative care, and how this specific type of care may work to uniquely shape the doctor-family partnerships. This study offers insight on solutions that can be implemented to ease this loss of relationship. Bereavement is greatly challenging for both the family and HCP (20), therefore it is of importance to address the misfortune of loss of relationship in order to promote the well-being of both parties. The objective of this study was to explore the thoughts and opinions of HCPs and families on their encountered loss of relationship at the end of home-based palliative care. We also aimed to understand of the dynamics of these relationship(s), which would in-turn provide context for the shared experiences and views.

Methods

Study design

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with palliative care professionals and the families of deceased home palliative care patients. Interviews with families were done 3 to 8 months (median 4 months) following their loved one’s death, representing various possible stages in the grieving process. To address the study objective, the concepts of HCP-family relationship dynamics in home palliative care, the experience of loss of relationship, opinions on contact after care has ended, and suggestions for solutions to ease hardship in this loss were explored. Semi-structured interviews, as compared to structured interviews, grant interviewees the freedom of flexibility and have a less rigid framework, allowing for various directions to be addressed (21).

Setting and participants

Participants were palliative care physicians (n=29) and nurse practitioners (n=3), as well as 31 family members of deceased home palliative care patients of Temmy Latner Centre for Palliative Care (TLCPC). Participants were accrued from May to August 2017. HCPs were from TLCPC, Mount Sinai Hospital, and University Health Network. All palliative care doctors in the homecare group were invited to participate in the study, however the nurse practitioners in this study were recruited by convenience sampling. Family member participants were recruited by convenience sampling from records of deceased TLCPC patients. Family members were excluded from the study if they: (I) were under 18 years of age; (II) were deemed to be emotionally or psychologically fragile by their physician. All family members in the study played an active role in the patient’s care, with the majority of them being primary caregivers.

Sample size

Sixty-three qualitative semi-structured interviews (32 HCP interviews and 31 family member interviews) were conducted with individuals who were eligible for the study and provided consent. This sample size allowed for the attainment of data saturation, which meant that new notions or themes were no longer raised in further interviews (21). Out of all approached HCPs, 15% declined participation, and 15% of approached family members also declined, most commonly due to limited time or lack of emotional readiness.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted in English, and two investigators (M Vierhout and J Varenbut) conducted the interviews face-to-face at a time and place convenient to the families and HCPs. Interview guides were utilized and questions included: “what was the nature of the home visits?” “do you think there should be a system in place so you can contact/see/speak to your patients’ families?” and “do you think a system that allows contact between you and your palliative care doctor would assist you in coping with the death of a loved one?”. Participants were encouraged to share as much information as they desired. Interviews were also audio-recorded, with the recordings later being transcribed verbatim. Demographic characteristics of participants were also collected.

Data analysis

The audio recordings of the interview responses were subjected to analysis through data-driven content analysis and grounded theory qualitative research methodology as described by Strauss and Corbin. The data were examined with open coding, which dissects the data and groups it into similar concepts, and axial coding, which is a more overarching notion that assembles the data into trends (21). Grounded theory approaches were used to investigate the thoughts of participants on loss of relationship. Throughout the full duration of the study, code collection was on-going. The construction of concepts employed a manifest approach to analyze the verbatim content of the interview transcriptions (meaning describing what the study participants said). Transcriptions were analyzed directly to search for congruity amongst the responses of participants. Overarching findings were then generated through the connection of similar concepts using both manifest content (referring to broad surface analysis) and latent content (referring to analysis of a more in-depth underlying meaning in the transcriptions). Inferences made by the authors included a consideration of context, referring to conditions that may have an effect on the responses of participants (21). The data was then developed to create 6 overarching themes. The collected information was analyzed by two of the authors (M Vierhout and J Varenbut), and the Principal Investigator (M Bernstein), while maintaining interrater reliability. The themes are relevant to the research question as they pertain to the process of home-based palliative care and are presented in chronological order, from relationship dynamics to after-death notions. This full understanding of the palliative care experience provides context for the opinions on loss of relationship.

Research ethics

All participants voluntarily took part in the study and informed consent was obtained. All collected data was kept secure, including audio recordings and interview transcriptions, with confidentiality being maintained. This study was approved by the Mount Sinai Hospital and University Health Network Research Ethics Boards.

Results

Demographic characteristics

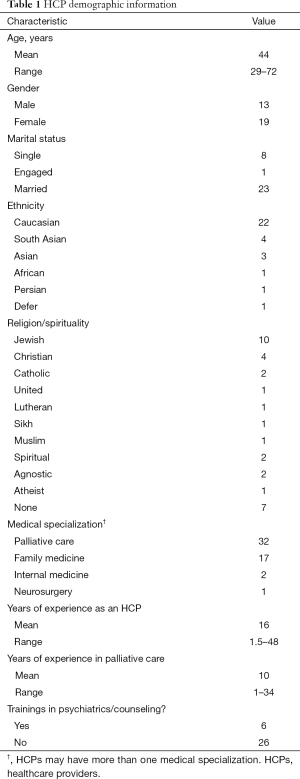

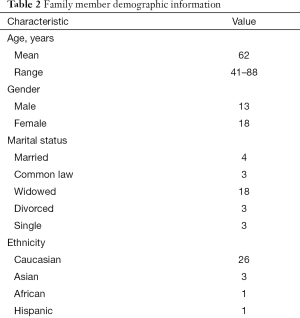

Thirty-two HCPs and 31 family members were interviewed. The mean and median age of HCP participants was 44 years old (range, 29 to 72 years old), while the mean age of family members was 62 years old and median age was 63 years old, with a range of 41 to 88 years old. The male to female ratio was 1:1.5 for HCPs and 1:1.4 for family members. Over 50% of the family participants were the spouse of the patient. All HCPs had a medical specialization in palliative care, and approximately 20% had formal training in counseling. Summaries of demographic information can be found in Tables 1,2.

Full table

Full table

Findings

Analysis of the transcripts yielded 6 overarching themes, which are described below and illustrated by quotes from participants.

Both HCPs and families recognize and appreciate the intimacy in home palliative care

HCPs and family members indicated that palliative care patients, and their respective families, are at a vulnerable stage. The nature of the care builds trust and intense connection between the HCP, patient, and family, that extends beyond solely medical care.

“It’s a lot more intimate than the typical doctor-patient and doctor-family member relationship. I find there is an extreme intimacy about it, what could even be seen as almost an embarrassing intimacy sometimes.” (HCP Interview 1, male, 66).

“He was there for us down to the details my mother’s last days. It’s a lot to see someone go through that, yet he was so compassionate.” (Family Interview 21, male, 41).

The unique HCP-family teamwork in home palliative care also gives rise to an elevated level of connectedness in the relationship.

“My goal, if possible, is to have a positive, trusting relationship with the family…understanding that when we provide palliative care, palliative care should be for the whole family not just the patient. And so, trying to engage with family and support them in the process of caring for a loved one with a terminal illness.” (HCP Interview 17, female, 32).

Additionally, the home setting is a contributing factor to intimacy. Families viewed HCPs as welcomed visitors in their homes, naturally drawing them closer.

“It was a great relationship. She belonged in our home, and would even sit down for a coffee.” (Family Interview 11, female, 79).

Both parties expressed awareness and dissatisfaction with the abrupt ending of relationship

During the time when the patient is alive, there is close correspondence and regular visits between the HCP and family. However, when the patient dies there is a sudden termination of this contact and an end of routine. HCPs and family members expressed that this is not ideal and is unnatural. Some family members even communicated that there is shock associated with this.

“They’re like a lifeline that you can follow while you go through this. And then there’s so much grief and this relationship just suddenly ends and there’s no closure. Everything had such an abrupt ending; my mother was gone and there was this sense of shock.” (Family Interview 20, female, 51).

The majority of HCPs also indicated that they commonly think about or are reminded of their past patients’ families.

“It’s a very strange thing. You’re involved in this intense process and then all of a sudden it just disappears. You really wonder about how they’re doing.” (HCP Interview 3, female, 31).

“If I drive past the street afterwards it reminds me, sometimes I get cards from the families and I’m reminded of them.” (HCP Interview 14, female, 36).

Open and clear communication with HCPs is beneficial to family members, and important even after patient death

Family members shared that after the immediate grief period and settling of events, it is common for numerous questions surrounding the case to arise.

“When someone dies there’s a whirlwind of overwhelming emotions and tasks to complete. When all that is finally over you sit and think, you need answers to your questions to find comfort. It’s important that the door is kept open.” (Family Interview 19, female, 59).

Various family members also indicated that communication with the doctor would have assisted in coping with the death of the loved one, but were reluctant to initiate it.

“I know the demand in this type of care is so great, there are so many sick people. He was so helpful but I felt guilty wanting to contact him after.” (Family Interview 2, female, 54).

Additionally, the family members predominantly specified that this communication would be most preferred through a visit or phone call.

HCPs recognize that resources are insufficient and there is a gap in bereavement services for family members

HCPs pointed out that the existing system is inadequate and bereaved families require support that is not disjointed. HCPs could play a greater role in the transition process.

“One thing I think we could do a better job of is bereavement follow up in general. Actively connecting to another support, such as a bereavement coordinator, that is easily accessible would be great.” (HCP Interview 3, female, 31).

Families and patients are viewed as a unit in palliative care. With this in mind, HCPs explained that the system should be refined to provide greater aid beyond the death of the patient.

“Resources are not sufficient. Our current system is not set up to give services beyond the death of the patient, but if we rethought that then it would be worthwhile. It makes a lot of sense in terms of the continuum of care and how you have more than the impact on your patient; it’s really the idea that you are continuing to care for the community.” (HCP Interview 32, female, 53).

A proposed system to mitigate precipitous loss of relationship has multiple perceived benefits

Post death communication is deemed to be of significant importance to families. HCPs believe that implementing a system for contact would provide guidance and clarity for bereaved families.

“I think knowing that there is a way and a mechanism would help people be reassured, especially if they are struggling with issues they have to deal with after the fact, where they go from here, and who to speak to if they have questions.” (HCP Interview 30, male, 37).

There is great variability amongst the needs of every family. It is believed that a communication system in place would assist with understanding and tailoring to individual needs, and determining the appropriate time for contact.

“From experience, you know, some of these families will definitely appreciate it, someone will call and check on them and their loved one is still remembered. And some families when you call, they keep it very short…and they feel like it’s a new chapter the next day. I feel like it would be beneficial for some people and it could be explored when you’re going through the process if they would want it, and we could put some sort of note in the file.” (HCP Interview 23, female, 39).

Additionally, a system would provide structure in the busy schedules of HCPs to ensure further communication occurs.

“The way the system is set up now I could not keep track of bereavement phone calls, but if there was something structured, I think it would be nice to do that at 1 month, within 1 month, and then again at 6 months or within a year.” (HCP Interview 29, male, 35).

Logistical challenges and boundary issues are concerns for HCPs

Many HCPs indicated time is a major barrier in continuing to communicate with bereaved family members, and that it may encroach on the care of their current patients.

“Time is always of the essence, right? I support it but practically I don’t know how it would happen. I think that’s the big challenge.” (HCP Interview 27, female, 34).

Boundary issues were also presented as a predominant worry.

“I think when you talk about a friendship or a continuing relationship with families, that gets into a very problematic boundary issue because you are operating out of your scope.” (HCP Interview 16, male, 31).

“Boundary issues are hugely important…personally to maintain friendships with people who I have taken care of would really jeopardize my ability to do this kind of work.” (HCP Interview 21, female, 46).

“Any situation where there is asymmetry of power poses a risk for boundary issues.” (HCP Interview 1, male, 66).

Discussion

HCPs and families identified benefits to having contact beyond the patient’s death. However, they also identified challenges such as limits of resources and boundary issues. Patient-focused family-centered care is an initiative that is a goal of modern medical practice, and aims to increase the quality of care and experience of patients and their families (22). It must be realized that there is no “one size fits all” system that will be suitable for all families who have lost a loved one in home palliative care. For example, although most families stated they would prefer a visit or phone call from the HCP, a few said they would rather receive an e-mail. Receiving a letter of condolence has shown to be beneficial by humanizing the passing and facilitating the connection between health care professionals and the caregivers. Additionally, some families may not want further contact with the HCP, as this may generate negative associations and memories (23). Sometimes it may simply be the case that the interaction with the doctor is too brief to establish a deeper connection. It is not uncommon for some patients to be referred to palliative care late in their illness and die soon after, sometimes even after just one or a few visits (24-27). Cases like these may not warrant future HCP-family contact. It is imperative to derive a system that allows HCPs to best define and address individual families’ needs.

In some instances, bereavement can lead to complicated grief. In a study by Prigerson et al. exploring bereaved elders, 20% of individuals ranked as complicated grievers (28). In a review by Stroebe et al., the dangers that can arise from bereavement, including mortality and morbidity, are explained (15). Bereavement follow-up is seen as a part of the palliative care service and is a key element of quality palliative care, according to the National Consensus Project (29). In some systems patients have access to 1 year of bereavement services through hospice benefit, and support is provided to families through services including bereavement visits, seminars, and support groups (30,31). When asked which palliative care team member they would like to receive further support from, the majority of family members speculated that they would prefer it be the palliative care doctor. However, it was posited by the HCPs that limited time as well as lack of resources and training are barriers to providing this help. Only 20% of the interviewed HCPs in our study had any formal training in counseling. In the homecare group interviewed, it is the intention of doctors to both care for the patient and assess the needs of the caregiver. Patients and families have access to a staff psychosocial counsellor, and caregivers can be referred to bereavement services near or once the patient has passed. The nurse assigned to the case routinely conducts a bereavement follow-up, but doctors typically do not. However, as pointed out by HCPs in this study, resources are not sufficient. Due to the nature of palliative care and emotional needs of families, incorporating standard bereavement training in palliative care specialization could yield benefit. Additionally, the incorporation of more interdisciplinary support in Canadian palliative care teams, such as social workers, bereavement counselors, and psychosocial physicians could be advantageous. As previously mentioned, anticipatory grief may affect family members in palliative care, and they may look to the physician for comfort and reassurance. Therefore, the transition to post-death bereavement support may be smoother with the physician’s involvement, instead of a direct changeover to other professionals. This may also result in easier closure for the family. However, since the available time of palliative care physicians is restricted by their continuous care for current patients, long-term bereavement support by the physician is most likely not feasible and should be allocated to other members of the interdisciplinary team.

In a study exploring the bereavement needs of family members, it was indicated that the requirements for the person who is performing follow-up should be someone who listens and someone who knows the patient and family (32). This suggests that bereavement support does not have to be solely a medical role, and makes way for involvement of an informal care network. Informal care networks, defined as any carers such as family, friends, and neighbours who provide care but not formal services, play a significant role for patients in end of life care (33). However, to prevent exploitation of these caregivers, synergy must be achieved between formal and informal counterparts. Horsfall et al. speaks about the current Australian approach, entitled the health-promoting approach to palliative care or HPCC. This approach comprises various components to end of life care, including death, dying, and bereavement (33). Therefore, the incorporation of these networks should be considered when addressing the issue of insufficient bereavement resources in a population requiring bereavement support.

In accordance with the aging population in Canada, informal caregiving for the elderly is a crucial component of the healthcare system. 80% of care of seniors in the community and 30% of services provided to seniors in institutions is provided by informal caregivers (34). The reformatting of the healthcare system to include more community informal caregiving working synergistically with HCPs could yield benefit for both palliative patients and their family members.

The present study has limitations. Firstly, HCP participants were all recruited from 3 closely associated institutions in a large university system in a socialized healthcare system. These institutions may have a standard of care and methods of practice that are distinct from other systems or cultures. Secondly, all family participants were derived from the practices of physicians from a single institution indicating a potential sampling bias. Thirdly, the present study interviewed only 3 nurse practitioners, recruited by convenience sampling, representing a small sample number and limiting the generalizability of these findings. The majority of HCPs interviewed are homecare doctors, therefore the views expressed in the study, as well as its focus, are primarily physician-oriented. In actuality there are professionals from various other disciplines providing palliative care, who also work in conjunction with palliative care doctors, and whose views are not presented in this study. We acknowledge the extremely valuable roles that other members such as nurses, personal support workers, and counsellors play. Further studies to explore the views of other professionals in palliative care are warranted and would provide valuable insight on this topic. Fourthly, as family members were recruited via convenience sampling and physicians arbitrarily indicated who was suitable for participation, there is the possibility that family members were missed by this method. Additionally, HCPs indicated which family members would be suitable for participation, there may have been a bias to pick family members where the relationship was fairly positive, or the case did not present complications. This raises the potential issue of selection bias. Lastly, since approximately 15% of HCPs and family members declined to participate in the study, it must be addressed that the interviewed participants may constitute a more vocal subsample, and hence raises the possibility of sampling bias, which is a frequent flaw in qualitative research.

Conclusions

The findings obtained in this study show how HCPs and families perceive the dynamics of home palliative care, and their thoughts regarding the loss of relationship after patient death. Home palliative care is more intimate than other types of medical care for a multitude of reasons, and this leads to an appreciable family-HCP connection. Overall, families and HCPs are dissatisfied with this sudden loss of relationship, and recognize the potential benefits of an approach that would allow for communication going forward. However, the exact details of such a system are not clear and need to leave space for families’ and HCPs’ individual needs.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend a special thanks to all participating HCPs who gave interviews. An immense appreciation is also extended to the TLCPC patient family members who graciously offered their time and generosity to be interviewed. This work was supported by Dr. Mark Bernstein, the Principal Investigator.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This study was approved by the Mount Sinai Hospital (16-0316-E) and University Health Network (17-5521.0) Research Ethics Boards. Written informed consent for participation was obtained from each participant.

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Definition of Palliative Care. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- Mercadante S, Genovese G, Kargar JA, et al. Home palliative care: Results in 1991 versus 1988. J Pain Symptom Manage 1992;7:414-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stajduhar KI. Examining the perspectives of family members involved in the delivery of palliative care at home. J Palliat Care 2003;19:27-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yedidia MJ. Transforming doctor-patient relationships to promote patient-centered care: lessons from palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:40-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rabow MW, Hauser JM, Adams J. Supporting Family Caregivers at the End of Life. JAMA 2004;291:483-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prigerson HG, Jacobs SC. Caring for bereaved patients: “all the doctors just suddenly go. JAMA 2001;286:1369-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adler HM. The Sociophysiology of caring in the doctor-patient relationship. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:874-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lundberg T, Olsson M, Fürst CJ. The perspectives of bereaved family members on their experiences of support in palliative care. Int J Palliat Nurs 2013;19:282-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Main J. Improving management of bereavement in general practice based on a survey of recently bereaved subjects in a single general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2000;50:863-6. [PubMed]

- Middleton W, Burnett P, Raphael B, et al. The bereavement response: a cluster analysis. Br J Psychiatry 1996;169:167-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murray PC. Coping with loss: Bereavement in adult life. BMJ 1998;316:856. [Crossref]

- Schulz R, Hebert RS, Dew MA, et al. Patient suffering and caregiver compassion: new opportunities for research, practice, and policy. Gerontologist 2007;47:4-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stroebe M, Schut H. The dual process model of coping with bereavement: rationale and description. Death Stud 1999;23:197-224. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simon NM. Treating complicated grief. JAMA 2013;310:416-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stroebe M, Schut H, Stroebe W. Health outcomes of bereavement. Lancet 2007;370:1960-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chapman KJ, Pepler C. Coping, hope, and anticipatory grief in family members in palliative home care. Cancer Nurs 1998;21:226-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bedell SE, Cadenhead K, Graboys TB. The doctor’s letter of condolence. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1162-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Candy B, Jones L, Drake R, et al. Interventions for supporting informal caregivers of patients in the terminal phase of a disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011.CD007617. [PubMed]

- Hudson PL, Thomas K, Trauer T, et al. Psychological and social profile of family caregivers on commencement of palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:522-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keene EA, Hutton N, Hall B, et al. Bereavement debriefing sessions: an intervention to support health care professionals in managing their grief after the death of a patient. Pediatr Nurs 2010;36:185-9. [PubMed]

- Strauss AL, Corbin JM. Basics of Qualitative Research 3rd ed. USA: Sage Publications Inc., 2007.

- Levinson W, Lesser CS, Epstein RM. Developing Physician Communication Skills for Patient-Centred Care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:1310-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barnett MM. Effect of breaking bad news on patients’ perceptions of doctors. J R Soc Med 2002;95:343-7. [PubMed]

- Humphreys J, Harman S. Late referral to palliative care consultation service: length of stay and in-hospital mortality outcomes. J Community Support Oncol 2014;12:129-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferrell BR. Late Referrals to Palliative Care. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2588-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schockett ER, Teno JM, Miller SC, et al. Late Referral to Hospice and Bereaved Family Member Perception of Quality of End-of-Life Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;30:400-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fink RM. Review of a Study on Late Referral to a Palliative Care Consultation Service: Length of Stay and In-Hospital Mortality Outcomes. J Adv Pract Oncol 2015;6:597-601. [PubMed]

- Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK, Reynolds CF, et al. Inventory of Complicated Grief: a scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res 1995;59:65-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, Center to Advance Palliative Care, Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, et al. National consensus project for quality palliative care: clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, executive summary. J Palliat Med 2004;7:611-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- VNSNY Hospice and Palliative Care. Our Services. Available online: https://www.vnsny.org/how-we-can-help/hospice-palliative-care

- Dana Farber Cancer Institute. Bereavement Support. Available online: http://www.dana-farber.org/for-patients-and-families/care-and-treatment/support-services-and-amenities/bereavement-support/

- Milberg A, Olsson EC, Jakobsson M, et al. Family members' perceived needs for bereavement follow-up. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35:58-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Horsfall D, Leonard R, Noonan K, et al. Working together–apart: Exploring the relationships between formal and informal care networks for people dying at home. Prog Palliat Care 2013;21:331-6. [Crossref]

- Carstairs S, Keon WJ. Canada’s aging population: Seizing the opportunity. Canada: Special Senate Committee on Aging, 2009.