The palliative APRN leader

Introduction

Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) are leaders in clinical practice, systems-level care delivery, nursing practice, and policy across settings. Palliative care leadership is about influence and change within a health care system and achieved through a myriad of foci. Today there is a national shortage of palliative care clinicians. APRN leaders will be necessary to guide the care for patients with serious illnesses and their families. Often hidden, APRN leadership is grounded in the Institute of Medicine reports—Future of Nursing, Dying in America and the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care Clinical Practice Guidelines. This paper reviews APRN leadership in palliative care in the domains of clinical care, education, advocacy/policy, research, and administration/management.

Overview

Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) are distinguished by their ability to synthesize complex data, implement advanced plans of care, and provide leadership in hospice and palliative care (1). The palliative APRN role has developed over the last 20 years. Unlike medicine which only 10 years ago recognized the specialty of palliative care, hospice and palliative nursing has been recognized as a specialty for over 25 years (2,3). The result is that APRNs have been palliative leaders in clinical practice, systems-level care delivery, nursing practice, and policy (2,4). Common scenarios include the trusted geriatric nurse practitioner (NP) who is asked to start a home-based palliative care program for patients who do not meet hospice or home health eligibility; the community hospital clinical nurse specialist (CNS) who is asked to start an advance care planning initiative as a way to integrate palliative care or who is directed to care for terminally ill patients in the hospital to assure good end of life care; or the APRN who is asked to assure palliative care education for all nurses within a federally qualified health clinic and take on seriously ill patients within designated providers as primary care patients.

The current health care system is burgeoning. The population is skewing towards 65 and older and these patients have complex needs. The costs of health care have escalated with the creation of new technology that is implemented without consideration of congruency of goals of care. Now more than ever, palliative APRN leaders are essential due to physician shortages. With just 1 million physicians to serve the needs of the diverse 325.7 million population of the United States, there is a significant shortage of physicians overall (5). This includes a shortage of palliative care physicians. Moreover, geographically, most physicians do not practice in the community and rural areas.

Often, the focus of palliative leadership is on coordinating and managing a palliative program. As palliative care moves out of the hospital into the community, APRNs are frequently established in the community, and can continue to lead initiatives in these areas. Current literature does provide evidence models of APRN led programs in a community academic hospital and the community settings (6-9). However, there are four other critical areas of leadership. Palliative leadership in education assures development in palliative knowledge, attitudes, and skills. Palliative care leadership in clinical practice promotes excellence and evidence-based practice in delivery of quality care. Palliative care leadership in research fosters the continued development and maturity of the evidence to support and grow the specialty. Palliative leadership in policy and advocacy furthers changes in health care, delivery, and access.

As within other areas, there are informal leaders and formal leaders. APRNs are often serve as informal leaders without titles, garnering respect of others through their longevity of team membership, an open mentoring process, or a nurturing style. APRNs are often long-standing members of the team who grow a program. Frequently, APRNs are not given the authority commensurate with responsibility, empowerment to lead, nor receive team and/or organizational acceptance into leadership roles (10). The challenge is that in the current fragmented and hierarchical healthcare environment, non-physician leadership in health care, as well as palliative care, is frequently underappreciated as demonstrated by lack of acknowledgement or recognition (11,12). There are frequent stories of program development or initiatives that start with a nurse, who is anonymous, and then when a physician, who is given a title, joins the program, he or she is cited as the leader of the program. The result is a dearth of literature specific to palliative APRN leaders and their leadership.

The 2014 Institute of Medicine’s report Dying in America—Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near End of Life identified five areas to achieve quality, sustainable, palliative care for all patients with serious and life-threatening illness across all settings: (I) delivery of person-centered and family-focused palliative care; (II) clinician-patient communication and advance care planning; (III) professional education in palliative care; (IV) policies and payment for palliative care; and (V) public education and engagement in palliative care (13). Because nursing and palliative care are synergistic, nursing has a large role in implementing recommendations related to these areas (Table 1). By the virtue of their increased scope of practice, APRNs are essential in each of these five areas as their scope of practice allows them to deliver the care, lead improved communication, initiate advance care planning programs, educate their peers and colleagues in palliative care, lead policy and advocacy in palliative care, and promote public and consumer education (2). Specifically, according to the Institute of Health Improvement, the combination of clinical skills and leadership skills promote innovative leadership and changes in health care (16).

Full table

APRN practice is based on patient-centered care, with the understanding that care does not occur in total isolation of a family (chosen or biological). As frontline clinicians, APRNs, along with their RN colleagues, spend the most time with patients at the bedside. Since all people die, all APRNs must have fundamental palliative care skills. This includes understanding illness trajectories from diagnosis to death, appropriate assessment and management of pain, particularly in the current opioid misuse epidemic. Knowledge of payment for palliative care services is essential in order to work with payers, and insurers to provide sustainable community clinical and social services. Clinical services, located in the outpatient and home setting, keep patients out of the acute care setting and include hospice, home health, comprehensive primary care services at home, and day care centers. Other social service resources include nutrition, transportation, pharmacies, legal aid, aging services, and disease specific organizations. Finally, APRNs have a range of opportunities and venues (formal and informal) in which to educate the public about what palliative care is and what it is not. This includes community centers, schools, senior centers, YMCAs and YWCAs, houses of worship, libraries, and professional organizations.

Leadership in palliative care

Leadership theory has evolved significantly in the past few years. In the past, the emphasis of nursing leadership was a mechanistic, scientific management perspective focused on an employer-employee model that was driven by rules, regulations, policies, and procedures. The present emphasis on nursing leadership embraces the dynamic and interdependent (organic) nature of complex adaptive systems, transformational leadership utilizes (17,18). Palliative care is certainly dynamic and interdependent with health care reform and requires transformational leadership of all disciplines.

Palliative care leadership is about social change that helps achieve a goal of quality care for persons with serious illness (6,7). It is characterized by: (I) leading team members or members within the organization who have a clear mission and vision of palliative care initiatives and programs; (II) motivating and inspiring others to provide and achieve excellence in palliative care, creating healthy work environments in which palliative care is provided; and (III) changing the behavior of others to work collaboratively in palliative care (19,20).

Palliative care leadership is grounded in the principles of the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care Clinical Practice Guidelines, specifically in the leadership needed to assure access to quality palliative care. APRN leadership includes personal mastery or continual growth in palliative nursing, clarity of palliative care models, shared vision of palliative care, team learning in the many aspects of palliative care, and an overall concept of palliative care within the context of healthcare (21) (Table 2).

Full table

Models of APRN leadership in palliative care

There is a new emphasis on leadership development in four particular areas. One is the role of strategist and knowledge broker. This is the APRN who moves beyond knowledge acquisition into translation of evidence into systems level practice (22). An example is the pain APRN who uncovers the inadequate management of pain for patients at the end of life on a surgical unit and she creates a strategy for education, creates resources, and metrics for pain management to help with quality care, appropriate lengths of stay, and evidence-based practice. Another example is the APRN who case manages for an accountable care organization and performs a goals of care conversation and palliative performance scale on all patients to determine the appropriate resources necessary to avoid hospital admissions. Two is the role of systems-level thinker, or the APRN who thinks about change at the high level (23-25). It is critical to understand the needs and the priorities of the various stakeholders within a health system as they are constantly evolving. An example is the Emergency Department (ED) APRN who understands that in order to be efficient and effective, the ED must both discharge non-critical patients to assure bandwidth for further admissions which simultaneously triage palliative care patients to consider their appropriate and successful disposition. Three is the role of utilization of data and evidence to promote practice. This is the APRN who uses metrics to assure better clinical care. An example is the oncology NP who consistently cites the evidence that early palliative care promotes better quality of life, less depression and anxiety and less hospitalizations, fewer ED visits for cancer patients which promotes the use of palliative care among her colleagues and patients and families (26-28). Fourth is the role of change agent who proactively scans and analyzes the environment to anticipate changes and respond (27,29). The is the medical-surgical CNS who promotes delirium assessment and management as a quality indicator with the understanding that Magnet survey will encourage a permanent change in practice.

In order to be successful, the Institute for Health Improvement offers five high-impact leadership characteristics that can be applied to APRN leadership: person-centeredness, frontline engagement, relentless focus, transparency, and boundarilessness (30). Person-centeredness is when the palliative APRN consistently embraces person-centered practices. This is fairly straightforward since palliative care is all about the patient/family as a unit of care. Front-line engagement is when the palliative APRN offers regular authentic presence on the front line of palliative care delivery and is a visible champion of improvement in palliative care. This occurs within every contact with patients, families, referrers and colleagues. Relentless focus is when the palliative APRN is focused on a vision of both palliative care and palliative nursing and a strategy to advance the profession and the specialty. This requires an exquisite understanding of palliative care upstream in health care versus hospice care at the end of life and the nuances in between. It also requires the understanding that optimal care delivery is achieved when nurses practice to the full scope of their license. Transparency is when the palliative APRN ensures information about results, progress, aims, and defects is visible and clear for all to understand. The honesty about the positives and negatives of palliative care promotes integrity. Boundarilessness is when the palliative APRN encourages, practices, and role model systems thinking, and collaboration across boundaries (30).

In 2017, the American Nurses Association (ANA) and the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association (HPNA) released the Call For Action—Nurses Lead and Transform Palliative Care (31). It describes how all nurses practice primary palliative care and may seek specialty palliative care expertise. Primary palliative care is the care for patients at the basic level utilizing common information. Specialty palliative care is the comprehensive approach to patients with serious illness based on expert practice, knowledge, and communication. The Call for Action focuses on the five areas clinical practice, education, policy, research and administration in which APRNs can lead and transform palliative care.

Clinical practice

Bob is a medical surgical CNS as a regional hospital. He has been called to create a culture of palliative care practice. In order to role model specialty palliative nursing practice, he has achieved advanced certification in hospice and palliative nursing (ACHPN). He collaborates with the general medical floor to create a newer focus on palliative care. This includes rounding with the nurses on their patients for palliative care issues for patients with new diagnoses of serious illness, advanced illness, and patients at the end of their lives. He also holds debrief rounds for difficult patients and is working with his nurse colleagues to create and update policies.

Clinical care is the most recognized area of leadership for APRNs. Numerous studies have demonstrated APRN effectiveness, quality, and safely (32-38). As providers of care across all health settings and therefore care for many patients with serious illness, APRNs play a vital role in each of these elements of palliative care (39). APRNs deliver quality palliative care throughout the United States in urban, rural and community settings including adult and pediatric day care centers, long term care centers, skilled nursing facilities, group homes, shelters, rehabilitation facilities, acute care settings, as well as the home.

To be successful, APRNs must understand the diagnosis and the natural trajectory of illnesses and diseases along with the critical decision-making points to manage and treat these conditions from diagnosis to end-of-life care, based on best available evidence. APRNs are in a prime position to deliver collaborative interdisciplinary palliative care for patients with serious illness and move palliative care upstream to caring for populations across the lifespan and across the health care continuum. This includes acute issues such as trauma or sudden illnesses such as stroke or myocardial infarctions. It also includes chronic issues such as congenital issues, as well as diseases related to neurology, cardiology, nephrology, hepatology, pulmonology, dementias, oncology, hematology, gynecology, and gastroenterology; in truth, all health conditions. Thus, APRNs not only lead clinical teams, they create and establish policies, procedures, and processes for quality delivery (2).

Education

Clare is a geriatric NP at a geriatric clinic who rounds at the adult day care center and provides wellness visits at the senior center. She has many students she precepts in educating them about the care of older adults with serious illness. Clare provides ELNEC training to all the nurses in the clinic as part of orientation. She holds information sessions at the senior center on advance care planning and assists people to complete the appropriate documents and get them to family and health providers. Clare also holds information session on choosing the right home services where she discusses hospice and palliative care.

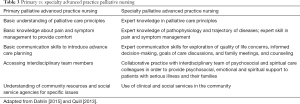

Education is often the second common area of leadership. As the most trusted health professional for the 15th year in a row, the public turns to nurses (both APRNs and RNs) for unbiased information (40). With their preparation in patient and family education, APRNs are positioned to create and lead palliative care education for consumers, peers and colleagues. APRNs can lead education in terms of clinical practice to other nurses, mentor and coach other nurses in primary and specialty palliative care (Table 3).

Full table

In a primary palliative role, the APRN promotes various palliative care skills (41,42). In order to promote patient-centered care, the APRN must educate others about hospice and palliative care services, eligibility, and how to access these services in his or her setting and community.

In the specialist palliative role, the APRN provides comprehensive pain and symptom management in all diseases, using complex decision-making to apply sophisticated regimens, while educating other colleagues on fundamental principles (41,42). In addition, the APRN fosters communication skills to explore quality of life, assure informed decision-making, discuss goals of care, conduct and lead family meetings, provide psychosocial and emotional support to patients and family, and to be present on the difficult journey of serious illness to end of life. This includes attention to cultural and spiritual dimensions of care as specified by the patient and family.

Lastly, the specialist palliative APRN must educate other colleagues and disciplines in how to develop an organized care plan in preparation for a patient’s dying in terms of setting, proactive pain and symptom management, and education for the patient, family and staff about the dying process.

This education may occur through the use of the End of Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) Curriculum which has been promoted as essential to all nursing practice (31), but also appropriate to education to other disciplines. A plethora of education tools, resources, and curricula are listed in the Appendix of the ANA and HPNA Call To Action. Three particularly helpful resources include: Multidisciplinary Care in the ICU, ConsultGeri, and Comfort Communication (31).

Policy/advocacy

Marron is an oncology CNS in a cancer center. She has been asked to work on payment for palliative care in the oncology setting. She has interviewed the insurers in her area to ensure they are aware of palliative care and its difference from hospice care. Marron is working with payers on metrics for cancer patients according to the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) standards for quality palliative care and pay for performance measures within the cancer setting. She is also working with the insurance companies on using only palliative care programs that are certified or have at least 1 certified palliative care clinician on staff. This can be a nurse, social worker, physician, chaplain, or administrator.

Policy and advocacy is an area where more nursing leadership is necessary, because less emphasis and development has been dedicated to this area. To lead in policy and advocacy, the APRN must fully engage with the issues. This will necessitate education about health care, health policy, pertinent health regulations and legislation. It includes how to address professional nursing issues, advanced practice registered nursing issues as well as advanced practice provider issues. To be successful, APRNs must position themselves as participants on national, regional, local, and organizational committees, workgroups, and coalitions to offer the nursing perspective and the advanced practice provider perspective. It also means developing organizational and collaborative skills to build coalitions and promote APRN full scope of practice to remove barriers to quality palliative nursing within organizations, federal and commercial insurers, as well as regulatory and legislative bodies. Current issues include APRN reimbursement and consistent APRN practice across the states and territories (31). However, it also includes working on outcomes that promote new models of care delivery, especially in the community such as home, clinic/office (particularly federally qualified clinics), long-term care settings, residential settings, group homes, shelters where the literature has revealed that APRNs serve more underserved populations (43).

Research

Alex is a psychiatric NP who is part of a school of nursing and an academic medical center. He is working with the school of nursing on a palliative care research agenda. He teaches two courses on research methods and uses palliative care studies as examples. In his role as nurse scientist for the academic medical center, Alex is working with the floor nurses on grief and bereavement indicators because that is an identified area of lack of knowledge. He is helping them create a quality improvement process for identifying grief and depression. He also precepts on a homeless team to assist with promoting a dignified death for that population.

As stated in the Palliative Nursing Scope and Standards, palliative nursing principles are part of every nurse’s practice. Moreover, evidence-based practice in palliative care has matured and evolved over the years. The APRN leader in research focuses on creating new research based on the National Consensus Project for Qualify Palliative Care Clinical Practice Guidelines, the priorities of Measuring What Matters, the National Quality Forums measures for palliative care and other palliative care metrics (44-47). This offers a dual focus in knowledge in palliative nursing and palliative care. Specific workforce issues include the extent of palliative care in undergraduate nursing education, palliative care content the graduate level, and workforce demographics. It should be noted that is no information on the number of APRNs who are practicing specialty palliative care on a national level. Capturing this data is difficult because palliative care is not a primary certification for APRNs, nor part of licensure. In addition, many APRNs do not recognize the elements of palliative care within their specialty practice such as in adult and pediatric critical care, specialty clinics, or alternative settings where serious illness is common.

Administration/management

Jackie is an adult NP who has worked at her health system for 10 years. It includes a hospice, a home health agency, an adult day care center, and a hospital. She has been asked to create a palliative care program that would cross all settings to assure all patients with serious illness have their needs addressed. Jackie looks for resources on program development and APRN leader role models. She seeks to understand the scope of practice around her role as administrator and clinician.

Administration and management is often the obvious domain APRNs consider when thinking about leadership. However, content about program development and business principles is not an emphasis in graduate nursing education resulting in few APRNs with experience with program leadership. Palliative care program or initiative development includes business planning, financing, implementation, with effective use of resources. It also includes understanding the various models of palliative care, new and old, with attention to novel nurse-led models (31). Previously, there was an emphasis on palliative care program development within hospital-based teams in the academic setting. More emphasis is now being focused on palliative care in community or rural hospitals; clinics attached to hospital teams; specialty disease clinics; or home-based models. New models include: (I) working with accountable care organizations, patient medical homes, and medical groups; (II) palliative APRN consultation models; (III) palliative APRN care coordination; (IV) APRN led long-term care models; and (V) palliative APRN private practices. Understanding business principles allows the APRN leader to explore and implement new models to promote care in the community to keep patients in the setting where they desire. However, other skills include effective leadership skills within a team as well as fostering and promoting leadership of other nurses and other team members.

Leadership development

Currently, there are not many educational resources for nursing leadership development outside of administration. Many internal courses for nursing leadership focus primarily on management rather than leadership. There are graduate programs for nurse executive leadership and management programs for running units. There are a few nursing organizations with leadership resources (Table 4).

Full table

Within the larger concept of administrative leadership, The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO) conducts a leadership and management conference with an administrator focus (47). The Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) promotes program development and leadership skills to grow a program within their Palliative Care Leadership Centers (48).

Conclusions

APRNs are in a prime position to lead and transform health care delivery for those with serious illnesses. Now more than ever, with a national shortage of palliative care clinicians, palliative APRNs must be given the opportunity to take on leadership roles. APRN leaders are essential for palliative care development and are needed in all areas of palliative care—clinical practice, education, policy/advocacy, research, and administration. To be effective, APRN leaders must consider their area of leadership and utilize the available broad palliative care and leadership resources. In this way, APRNs will participate in the evolution the field of palliative care to meet the needs of patients with serious illness and their families while promoting access to quality palliative care.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. Competencies for the Hospice and Palliative APN. Pittsburgh, PA: Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association; 2014.

- Dahlin C, Coyne P. History of the Advanced Practice Role in Palliative Nursing. In: Dahlin C, Coyne P, Ferrell B, editors. Advanced Practice Palliative Nursing. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Coyne PJ. Evolution of the Advanced Practice Nurse within Palliative Care. J Palliat Med 2003;6:769-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life Care. Advanced Practice Nurses Role in Palliative Care - A Position Statement from American Nurse Leaders. 2002. Available online: https://www.promotingexcellence.org/downloads/apn_position.pdf

- Statistics & Facts on U.S. Physicians/Doctors New York, NY: Statista Inc.; 2018. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/1244/physicians/

- Prince-Paul M, Burant CJ, Saltzman JN, et al. The effects of integrating an advanced practice palliative care nurse in a community oncology center: a pilot study. J Support Oncol 2010;8:21-7. [PubMed]

- Deitrick LM, Rockwell EH, Gratz N, et al. Delivering Specialized Palliative Care in the Community: A New Role for Nurse Practitioners. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2011;34:E23-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Owens D, Eby K, Burson S, et al. Primary palliative care clinic pilot project demonstrates benefits of a nurse practitioner-directed clinic providing primary and palliative care. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2012;24:52-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gibson S, Bordofsky M, Hirsch J, et al. Community Palliative Care: One Community’s Experience Providing Outpatient Palliative Care. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2012;14:491-9. [Crossref]

- Kornacki M. Three Starting Points for Physician Leadership. NEJM Catalyst: Physician Leading, Leading Physicians [Internet]. 2016. Available online: https://catalyst.nejm.org/three-starting-points-physician-leadership/.

- Goldsberry J. Advanced practice nurses leading the way: Interprofessional collaboration. Nurse Educ Today 2018;65:1-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mildon B, Cleverly K, Strudwick G, et al. Nursing Leadership: Making a Difference in Mental Health and Addictions. Nurs Leadersh (Tor Ont) 2017;30:8-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Dying in America – Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near End of Life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014.

- American Nurses Association. Nursing Scope and Standards of Practice. 3 ed. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association; 2015.

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 3 rd ed. Dahlin C, editor. Pittsburgh, PA: National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care; 2013.

- Angood P, Birk S. The Vallue of Physician Leadership. Physician Exec 2014;40:6-20. [PubMed]

- Chaffee MW, McNeill M. A model of nursing as a complex adaptive system. Nurs Outlook 2007;55:232-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wheatley M. Leadership and the new science: discovering order in a chaotic world. 3rd ed. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler; 2006.

- Altillio T, Dahlin C, Remke SS, et al. Strategies for maximizing the health/function of palliative care teams: a resource monograph from the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC). New York, NY: Center to Advance Palliative Care; 2014.

- Speck P. Leaders and Followers. Teamwork in Palliative care - fulfilling or frustrating. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006:65-82.

- Advancing Expert Care, Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, Hospice and Palliative Nurses Foundation, Hospice and Palliative Credentialing Center. Position Statement: Palliative Nursing Leadership Pittburgh, PA: Advancing Expert Care; 2015. Available online: http://hpna.advancingexpertcare.org/education/position-statements/

- James KM. Incorporating complexity science theory into nursing curricula. Creat Nurs 2010;16:137-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Porter-O’Grady T, Malloch K. Leaders of innovation: transforming postindustrial healthcare. J Nurs Adm 2009;39:245-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2011.

- Porter-O’Grady T. Leadership at all levels. Nurs Manage 2011;42:32-7. [PubMed]

- Grant B, Colello S, Riehle M, et al. An evaluation of the nursing practice environment and successful change management using the new generation Magnet Model. J Nurs Manag 2010;18:326-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shirey MR. Establishing a sense of urgency for leading transformational change. J Nurs Adm 2011;41:145-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trybus MA. Facing the challenge of change: Steps to becoming an effective leader. Delta Kappa Gamma Bulletin. Spring 2011:33-36.

- Porter-O’Grady T. A different age for leadership. J Nurs Adm 2003;33:173-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Swenson S, Pugh M, McMullan C, Kabeenal A. High-Impact Leadership: Improve Care, Improve the Health of Populations and Reduce Costs. Institute for Healthcare Improvement White Paper Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2013. Available online: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/HighImpactLeadership.aspx

- American Nurses Association, Hospice and Palliative Nurse Association. A Call for Action - Nurses Lead and Transform Palliative Care. Silver Spring, MD 2017. Available online: http://www.nursingworld.org/CallforAction-NursesLeadTransformPalliativeCare

- Babine RL, Honess C, Wierman HR, Hallen S. The role of clinical nurse specialists in the implementation and sustainability of a practice change. J Nurs Manag 2016;24:39-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists. Impact of the Clinical Nurse Specialist Role on the Costs and Quality of Health Care Philadelphia, PA: NACNS; 2013. Available online: http://www.nacns.org/docs/CNSOutcomes131204.pdf

- National Governors Association. The Role of Nurse Practitioners in Meeting Increasing the Demand for Primary Care. Washington, DC; 2012.

- Newhouse R, Stanik-Hutt J, White K, et al. Advanced practice nurse outcomes 1990-2008: A systematic review. Nurs Econ 2011;29:230-50. [PubMed]

- Selway J. Nurse practitioners: a vital force in healthcare delivery. Am Nurse Today 2012;7:8-11.

- Soltis LM. Role of the Clinical Nurse Specialist in Improving Patient Outcomes After Cardiac Surgery. AACN Adv Crit Care 2015;26:35-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stanik-Hutt J, Newhouse RP, White KM, et al. The Quality and Effectiveness of Care Provided by Nurse Practitioner. J Nurse Pract 2013;9:492-500. [Crossref]

- Reuben DB, Ganz DA, Roth CP, et al. Effect of nurse practitioner comanagement on the care of geriatric conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:857-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gallup News. Americans Rate Healthcare Providers High on Honesty, Ethics, Chicago, IL: Gallup, Inc.; 2016 [updated December 16, 2016]. Available online: http://news.gallup.com/poll/200057/americans-rate-healthcare-providers-high-honesty-ethics.aspx?g_source=Social%20Issues&g_medium=lead&g_campaign=tiles.

- Dahlin C. Palliative Care – Delivering Comprehensive Oncology Nursing Care. Semin Oncol Nurs 2015;31:327-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Quill TE, Abernathy AP. Generalist plus Specialist Palliative Care - Creating a More Sustainable Model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xue Y, Intrator O. Cultivating the Role of Nurse Practitioners in Providing Primary Care to Vulnerable Populations in an Era of Health-Care Reform. Policy Polit Nurs Pract 2016;17:24-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- LeBlanc TW, Ritchie CS, Friedman F, et al. Special Series on Measuring What Matters: Adherence to Measuring What Matters Items When Caring for Patients With Hematologic Malignancies Versus Solid Tumors. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;52:775-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dy SM, Kiley KB, Ast K, et al. Measuring what matters: top-ranked quality indicators for hospice and palliative care from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:773-81. [Crossref]

- Burstin H, Johnson K. Next-Generation Quality Measurement to Support Improvement in Advanced Illness and End-of-Life Care. Generations 2017;41:85-93.

- Kerr K. Metrics and Measurement for Palliative Care Alexandria, VA: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization; 2016. Available online: https://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/palliativecare/PALLIATIVECARE_Metrics%20_Measurement.pdf

- Center to Advance Palliative Care. Palliative Care Leadership Centers New York, NY: CAPC; 2018. Available online: https://www.capc.org/palliative-care-leadership-centers/palliative-care-training-locations/