Scotland’s public health palliative care alliance

Introduction

This article describes the origins, rationale and work of Good Life, Good Death, Good Grief (GLGDGG) a national alliance of organisations and individuals working to promote more open and supportive attitudes and behaviours relating to death, dying and bereavement in Scotland. The article considers challenges and responses, achievements and learning during the 6 years since the alliance’s inception. More information about GLGDGG can be found at its website (1).

Scottish context

Scotland is one of the four nations which comprise the United Kingdom. It has a population of 5.4 million. Features of Scotland’s changing demography include: increasing life expectancy (and a smaller increase in healthy life expectancy); high levels of health inequality; increased prevalence of long term conditions and multi-morbidity; more people dying in advanced old age; more babies, children and young people with life limiting conditions living longer. Social trends include growing geographic mobility, the decreasing numbers identifying with organised religion and increasing social isolation and loneliness.

Despite being both universal and profound, the experiences of death, dying and bereavement have some of the characteristics of marginal issues in Scottish society. There are low levels of public and professional awareness, knowledge, discourse and engagement relating to these issues. There is also a lack of good data on the scope and performance of formal and informal services, on the cost-effectiveness of service models and on the experiences of people in the final phases of life and bereavement.

In surveys, people in Scotland report themselves to be comfortable talking about death, dying and loss, and report that more talk about these issues would be a good thing (2). In the same surveys people report that they themselves have not talked about these issues, and also that they have not taken steps to prepare for the final stages of life.

Origins and rationale of GLGDGG

GLGDGG was established in 2011 by the Scottish Partnership for Palliative Care (SPPC), a non-governmental not-for-profit organisation (3). The establishment of GLGDGG was in line with Scottish Government (SG) policy of the time (4), and SG provided a small amount of funding to SPPC with which to initiate GLGDGG.

People’s experiences of death, dying and bereavement are only partially determined by formal health and social care services. The remit of GLGDGG is to influence a wider range of social, cultural and other environmental factors which impact on people’s experiences towards the end of life. GLGDGG adopts a public health palliative care (PHPC) approach to this work (5). A working definition of PHPC is provided below in the Challenges section of this paper.

About GLGDGG

Aims

GLGDGG is an alliance of organisations and individuals committed to creating a Scotland where:

- People are well-informed about the practical, legal, medical, financial, emotional and spiritual issues associated with death, dying and bereavement;

- There are adequate opportunities for discussion of these issues, and it is normal to plan for the future;

- Public policies acknowledge and incorporate death, dying and bereavement;

- Health and social care services support planning ahead and enable choice and control in care towards the end of life;

- Communities and individuals are better equipped to help each other through the hard times which can come with death, dying and bereavement.

Membership

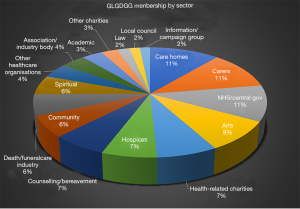

As at November 2017 GLGDGG has over 1,100 members—800 individuals and 300 organisations. The membership is quite diverse. As well as organisations which might be expected to have an interest (all state health providers, all Scottish hospices) there are also arts organisations, schools, local government, faith groups and legal practices amongst others. Figure 1 shows the composition of the alliance by type of organisation as at November 2017. GLGDGG has also engaged with many other organisations.

Approach

There is a risk that imposing public health initiatives on a community can be counter-productive, since without community involvement in the development of initiatives, they are likely to lack local support, be misguided and therefore be unsustainable.

The guiding principle underpinning SPPC activity at national level has been that different groups and communities within Scotland have different strengths, weaknesses, problems and priorities relating to death, dying and bereavement. Those groups and communities themselves know best what their strengths, weaknesses, problems and priorities are.

Therefore, GLGDGG is non-prescriptive in its approach, aiming rather to provide a support and a sounding board to build the capacity and inclination of individuals and organisations to undertake the change they think needs to happen in their local area.

Community development is a process where community members come together to take collective action and generate solutions to common problems. Community development work is generally done at a local level, and therefore a national organisation such as the SPPC cannot claim to undertake community development work.

However, the SPPC has attempted to apply the philosophy and some practical elements of a Community Development approach to its national work by:

- Finding out about the needs, problems and barriers faced by GLGDGG members and working to build on their existing assets. For example, time and money are key issues for GLGDGG members, while key assets include expertise, enthusiasm and networks;

- Enabling the GLGDGG community to have their say on relevant issues by aiming to influence relevant public policy developments;

- Developing new opportunities and maintaining an awareness of existing projects. For example, GLGDGG creates opportunities for its members to influence future priorities relating to PHPC work and actively looks for opportunities for members to work together on projects;

- Helping to raise public awareness about relevant issues. For example, GLGDGG is active on social media, fields speakers to a range of events, and is proactive in engaging with local, national and specialist media on issues relating to death, dying and loss;

- Encouraging members to take action by creating focal points for activity;

- Building links with other groups and agencies, for example GLGDGG has strong relationships with SG, Health and Social Care Partnerships, and links into various different types of organisations including charities, arts organisations and academic institutions;

- Raising funds, for example by submitting funding applications, and making the case to SG for increased investment in this area;

- Building a community of practice and enabling networking and sharing of learning.

The GLGDGG approach has also been influenced by the very limited financial and staff resources available to SPPC to support and develop the alliance—to make maximum impact, GLGDGG has focused on what it is best-placed to deliver well. A lack of significant central resources has helped to reinforce non-hierarchical relationships between SPPC and members of the alliance.

Portfolio

GLGDGG’s approach is primarily to engage, support and enhance the assets of communities, organisations and individuals who have the potential to improve the experience of death, dying and bereavement in Scotland. The SPPC undertakes the following portfolio of GLGDGG-branded work to support and nurture the alliance.

Providing infrastructure

SPPC has developed and updates the GLGDGG website through which resources are freely available to all. Regular newsletters are produced sharing news with and across the membership. Periodic networking events are run, and when funds occasionally allow, small grants are made available to members (and other interested organisations). A centrally recruited volunteer with training skills has been made available to groups wanting to develop informal community capacity around death, dying and bereavement discussion and support.

Developing resources

Films, leaflets and some other more experimental resources (beer mats, origami, a Dining with Death menu) have been developed for use by alliance members.

Policy, promotion and events

The importance of PHPC has been promoted to decision makers through input to public policy making processes. Old and new media coverage has been generated both to promote the alliance and also to highlight relevant issues. An annual awareness week is coordinated to provide a hook for local action. In the first week of November each year SPPC leads To Absent Friends (TAF), a people’s festival of storytelling and remembrance which again creates very broad and inclusive opportunities for participation. This festival is explored in more detail in the subsequent section on Key Successes.

Challenges and responses

In leading and supporting GLGDGG, the SPPC has faced some major challenges which are explored below. The response to each challenge is also outlined.

Resources

Challenge

The leadership and development of GLGDGG have been undertaken with minimal resources. In 2011 the SPPC staff team (5 people, some part time) added this work alongside their other responsibilities—no new staff resources were available. Between its inception in 2011 and the end of the financial year 2014/15 GLGDGG received an average of USD$ 11,000 per year from SG.

The absence of recurrent and predictable funding for GLGDGG has posed challenges in terms of making mid- and long- term work plans, and employing additional staff. An interesting comparison in terms of resource allocation is See Me a Scotland-wide campaign to end mental health discrimination. Stigma associated with mental health is society-wide issue, stemming from deeply rooted attitudes and beliefs, which can result in harms to individuals and communities. In this respect it is comparable to the issues GLGDGG is working to address, which are similarly wide ranging, deeply rooted, and negative for society. The See Me mental health stigma work received USD $1.3 m per year—a recognition that a challenge of this scale requires allocation of significant resource.

Response

Scarcity of resources has made it even more essential for the leadership of GLGDGG to adopt a grassroots sustainable approach—focussing on engaging, supporting and enhancing the assets of alliance members. This approach also helps to ensure that local work is informed and led by an understanding of local context which could never be achieved by a well-resourced top-down approach.

Lack of financial resources has necessitated SPPC finding creative, opportunistic and innovative ways to support this work—much draws on the good will of personal or professional connections. An example is Death on the Fringe (6), which has taken place every August since 2014—wanting to run some sort of festival of death but lacking any money, a volunteer was found to curate a “festival within a festival” capitalising on the Edinburgh Festival Fringe which takes place every year.

Breadth of agenda

Challenge

A great variety of factors impact on people’s experiences of death, dying and bereavement, for example: funeral poverty, multiple strands of public policy, legal frameworks, individual knowledge and capacity, social networks, health systems. This can make it difficult to communicate clearly and succinctly what GLGDGG is about.

People and organisations join GLGDGG for all kinds of reasons, and bring with them a diverse range of agendas. For example, GLGDGG encompasses those who are interested in bringing death education into schools; reducing funeral poverty; improving informal community support for people who’ve been bereaved; enabling family to undertake care of loved ones at home after death; encouraging greater uptake of Power of Attorney; improving communication skills of health and social care staff; building compassionate communities; and much more.

How can a national ‘alliance’ with a tiny staff team support such a vast range of issues and priorities? The range of possible areas of action is enormous and this creates a challenge of prioritisation.

Response 1

To help structure thinking and to aid clear communication SPPC has developed a working definition of what PHPC is, drawing on the work of Karapliagkou and Kellehear (5):

The term ‘public health palliative care’ is used to encompass a variety of approaches that involve working with communities and wider society to improve people’s experience of death, dying and bereavement.

Public Health Palliative Care Approaches are not about:

- therapeutic interventions with individual patients

- therapy

- improving how a service delivers therapeutic interventions

- creative or unusual ways of delivering therapeutic interventions

Rather, public health approaches to palliative care encourage communities to develop their own approaches to death, dying, loss and caring.

Public health approaches to palliative care are focused on:

- helping to prevent social difficulties around death, dying, loss or care, or;

- minimising the harm of one of the current difficulties around death, dying, loss or care, or;

- early intervention along the journey of death, dying, loss or care.

Public health approaches aim to change the setting/environment for the better, are participatory, and ideally should be sustainable and capable of evaluation.

These approaches can be underpinned by a variety of methods, such as:

- community engagement

- community development

- health promotion

- education

- changes to the social or policy environment

- social marketing

Response 2

To think through and organise its GLGDGG work, the SPPC has made use of the five action areas of the Ottawa Charter (Building healthy public policy, Creating supportive environments, Strengthening community action, Developing personal skills, Re-orienting health care services toward prevention of illness and promotion of health) (7). More recently it has made some use of the ISM model of influencing behaviour to think through the interrelationships between different potential interventions (8).

SPPC has also drawn on Kellehear’s ‘Big 7’ to develop a loose set of criteria to help focus its plans for future GLGDGG work:

- Focus of activity

- Does the activity aim to prevent social difficulties around death, dying, loss or care?

- Does the activity aim to minimise harms associated with death, dying, loss or care?

- Is the activity an early intervention in the causal chains leading to harm?

- Multipliers, participation, sustainability

- How far does this activity engage other organisations/individuals in relevant work?

- How far does this activity build the capacity of other organisations/individuals to undertake relevant work?

- Is the activity likely to be sustained?

- Outcomes and evaluation

- Is it likely that this activity will lead directly to a specific behavioural change?

- Is it likely that this activity will contribute indirectly to a specific behavioural change?

- Does this activity complement work by GLGDGG or by others on other factors which lead to a specific behavioural change?

- To what extent is it possible to evaluate the impact of this activity?

- How will this activity actually be evaluated, in practice?

- Niche

- Is GLGDGG well equipped to do this activity (skills, knowledge, networks, £ and time)?

- Is this activity better done by another organisation?

- Will this activity be done by another organisation if GLGDGG doesn’t do it?

- Bang for buck

- Is the expected outcome/output proportionate to the required resource input?

Lack of evidence

Challenge

There is a shortage of evidence specific to public health approaches to palliative care. In Scotland there is some evidence relating to the efficacy of anticipatory care planning but it is quite clinical in focus. There has been some evaluation work done around a Scottish mass media campaign to encourage to the public to grant a power of attorney (a proxy decision maker in the case of loss of capacity). Evidence from other countries on PHPC is also quite limited. This lack of evidence is an obstacle to advocating for action in this area. It also makes it harder to decide what work to do and provides little help in choosing between alternative areas of focus.

Response

GLGDGG has adopted a pragmatic approach, recognising that lack of evidence is not a basis for inaction. Informal exploration of evidence for approaches in related fields and in other countries has been undertaken, with an awareness of the risks of unthinking translation. Note has also been taken of the “informed opinions” of practitioners and public. At times, GLGDGG has used lack of evidence as a rationale for small scale innovation. More recently SPPC staff are working with colleagues at the University of Edinburgh and La Trobe University Melbourne to produce a more formal international scoping review, the methodology for which has recently been published (9).

Operationalising theories and slogans

Challenge

Many individuals and organisations accept and understand that to improve people’s experiences of death, dying and loss there is a need to move beyond traditional service-centric thinking and activities. Yet whilst it is true that “palliative care is everyone’s business”, it can be difficult to translate this exhortation into practical actions relevant to a range of contexts.

Much of the interest in ‘public health palliative care’ and GLGDGG comes from palliative care organisations whose core business is service delivery—skills and resources for activities such community development or public education may be limited. On the other hand those organisations with skills in these relevant domains usually have other priorities and can sometimes feel they lack subject knowledge or expertise around death, dying and bereavement and are cautious about entering emotionally sensitive territory. In both cases activity is often likely to be taken forward as a result of individual commitment and passion rather than their employer’s organisational strategy.

Response

GLGDGG’s portfolio of activities and resources has been developed bearing in mind the challenge of translating theory into practical, scalable local action. Efforts have been made to offer ideas and practical resources which can be adapted for local use depending on context and time available. As described in more detail below, annual events such as an Awareness Week and the TAF festival provide a stimulus, rationale and “official excuse” for action of all sorts. The It Takes a Village (ITAV) Exhibition is designed to bring important issues to light, in a meaningful and approachable way, with minimal effort from those who host the exhibition. Work has been done to proactively target and support “non-palliative care organisations”, sometimes linking them with expertise in death, dying and bereavement.

Risk aversion

Challenge

Organisations and individual practitioners sometimes bring a very cautious attitude to engaging with issues around death, dying and loss. This is sometimes expressed as generalised concerns about sensitivities or more specific concerns about doing harm. On other occasions caution is not explicitly expressed but appears to lie behind a lack of engagement. Engaging directly with the public in public places tends to heighten concerns. This risk aversion is well intentioned, but can be a barrier to action and lead to the harms which flow from these issues remaining hidden from the public domain.

Response

Work in this area isn’t risk free, but the risks need to be weighed against the risks of doing nothing. Through providing resources which are designed to be usable in public spaces such as photo-exhibitions and Before I Die Walls, GLGDGG has modelled and tested the acceptability of this sort of public engagement. Having ‘tried and tested’ resources and activities can help to build confidence and overcome risk aversion.

Demonstrating impact

Challenge

GLGDGG aims to achieve a range of attitudinal and behavioural change across the Scottish population. Progress against these aims is difficult and expensive to measure at population level. Rapid change is unlikely and so it would be necessary to measure over a long period of time. In addition, the consequences of a change in attitude or behaviour (e.g., planning for care costs) may not occur until a long time after that change. Being able to establish causality is a further huge obstacle. Most work is carried out by members of the alliance, and that makes it harder to measure the scale of activity, because the leadership of GLGDGG is one step removed, without the desire or ability to impose reporting requirements.

Response

In the absence of adequate resources to commission and sustain robust measurement of outcomes at population level GLGDGG has gathered activity data, and identified a range of relevant (though limited) proxy indicators. Proxy indicators have included the number of Powers of Attorney registered with the Office of the Public Guardian and the number of people on the palliative care register (or with an anticipatory care plan) held in general medical practices. A number of UK-wide social attitude surveys commissioned by others have explored end of life issues, one example being the 2012 British Social Attitudes Survey (10). Scottish data can be disaggregated from these surveys, but frustratingly doesn’t reach statistical significance. Activity is easier to measure. Data is gathered on numbers and type of membership, website activity, resource downloads and social media metrics. Instances have been identified where GLGDGG has influenced public policy. Informal evaluations of awareness weeks and of TAF have been undertaken (more details in the following section).

In a climate of limited resources there is always a balance to be struck between ‘doing’ and ‘measuring’. GLGDGG has consciously adopted an experimental and exploratory approach with an emphasis on doing, which has seemed appropriate given the stage of development of the field.

Some key successes

Growth and development

Six years on from the inception of GLGDGG the alliance has survived and grown. Membership and the level and diversity of activity have grown. The range of communities engaged in work has broadened. A solid portfolio of resources, activities and events has been developed and tested.

TAF, a people’s festival of storytelling and remembrance

Bruce Rumbold and Samar Aoun have looked at bereavement as part of a public health perspective on palliative care, suggesting that it is important to develop community capacity to support people who have been bereaved (11). TAF is a practical response to this challenge (12).

TAF is a Scotland-wide festival of storytelling and remembrance which takes place annually from 1–7 November, initiated by GLGDGG in November 2014. Born from a desire to reduce the social isolation of people who have been bereaved, TAF gives people across Scotland an excuse to remember, to tell stories, to celebrate and to reminisce about people who have died but who remain important to them (13).

TAF is designed to be of relevance to a wide range of circumstances—it is not just about recent loss, but can also be an opportunity to remember people who died many years ago. TAF encompasses grief, loss, bereavement, celebrating, mourning, remembering and memorialising.

TAF exists to encourage participation, and it is non-prescriptive and unbranded—groups and individuals are encouraged to take part in whatever manner they feel is appropriate. It is an opportunity to revive lost traditions and create new ones. The festival takes place across Scotland in public spaces, over social media, among friends, families and communities, and in people’s minds and hearts. TAF is not an awareness week or a fundraising venture.

GLGDGG promotes the festival, encourages involvement, provides ideas and support, and organises a small number of events. However, the vast majority of the activity which takes place during the festival is conceptualised and carried out by individuals and organisations on their own initiative. Events and activities range in size and scope, and it can be helpful to think of them as falling into four categories: public events open to all; community events run by organisations for their own members and invitees; private events enacted by individuals, families and groups of friends; online activities.

TAF has taken place annually since 2014, and continues to grow and develop. In addition to the intrinsic benefits reported by those taking part, the festival has proved a very effective way to achieve engagement between GLGDGG and a wide range of organisations and “hard to reach” groups (some examples: prisoners; the national symphony orchestra; people bereaved through substance misuse; a major professional football club; people with profound learning disabilities; schools). An evaluation of TAF suggests that taking part is an acceptable and positive experience, with most participants returning to take part in subsequent years (14).

ITAV: an exhibition

Health and care professionals often highlight low levels of public understanding of what palliative care is. PHPC highlights that only a small part of people’s experiences of deteriorating health, dying and bereavement takes place in the context of formal services. GLGDGG developed an initiative to address both these issues simultaneously, using an accessible and versatile medium—stories and photographs.

There is a well-known African proverb that ‘it takes a village to raise a child’. The ITAV exhibition explores the idea that it also takes a village to support someone who is dying (15). Based on interviews and portrait photography the exhibition illustrates that though much fantastic palliative care is provided by doctors and nurses in hospitals and hospices, this is only part of the story. Alongside a doctor, a nurse and an undertaker the exhibition features some perhaps less expected roles—a son, a daughter, a taxi driver and a teacher.

Designed to be displayed in any public space the exhibition is intended to:

- Affirm people’s experiences of caring and loss;

- Reduce isolation as the exhibition illustrates how death, dying and bereavement are universal issues, happening everywhere, right now;

- Promote sharing of experiences through conversations prompted by the exhibition;

- Encourage learning about death, dying and bereavement from the roles and experiences of people pictured in the exhibition;

- Increase awareness of the range of support available to help when someone’s health is deteriorating and they are approaching the end of their life;

- Provide an opportunity for those viewing the exhibition to consider how they might provide practical or emotional support to others going through difficult times;

- Break down the divide between professional and informal roles (the professionals illustrated share their reflections as human beings, not as the purveyors of expertise).

Copies of the exhibition are available to loan free of charge to anyone who can provide a venue for display. It has proved to be a popular resource which has toured public and private spaces across Scotland since its launch in May 2016.

Public policy

Public policies which acknowledge and reflect the experiences of death, dying and bereavement provide a more helpful context in which to make progress. By engaging with policy making processes GLGDGG has helped to ensure that this agenda is more frequently featured in relevant public policy. Examples of success include: Active Healthy Ageing An Action Plan for Scotland 2014–2016 (16); Optimising Older People’s Quality of Life: an Outcomes Framework Strategic Outcomes Model (17); Scottish Parliament Inquiry into Palliative Care (18); Strategic Framework for Action on Palliative and End of Life Care (19); Making it Easier—a health literacy action plan for Scotland (20). GLGDGG also engaged with Scotland’s network of public health directors to encourage and support the production of Palliative and End of Life Care in Scotland: the case for a public health approach (21).

Learning

Reflecting on 6 years of GLGDGG some lessons has been learned:

- Enthusiasm exists for PHPC in all kinds of places—not just in health and social care;

- Local ownership is a key ingredient for success of local activities, and by adopting elements of a community development approach a national infrastructure can be created that is facilitative and non-prescriptive;

- Local organisations appreciate and use centrally created resources such as leaflets, conversation menus and exhibition displays. Often, people wish to take action but lack the time or resources to come up with ideas, and are pleased to make use of resources, ideas and opportunities suggested by GLGDGG;

- Some successes can be achieved with minimal resources—GLGDGG small grants schemes have illustrated how small amounts of money (less than USD $300) can make a big difference to local work;

- National events such as awareness week and TAF act as a catalyst for local activities;

- National events are likely to be most effective if they are based on a meaningful idea, and are simple and cheap to participate in;

- Original work attracts helpful media interest, and this can come in all shapes and sizes, including local, national and specialist publications.

The way forward

In 2017, SG provided welcome additional funding, sufficient to employ a Development Manager for 2 years over the period 2017–2019. In this next phase of development the initial priority is to scale up some existing activities and initiatives, and to strengthen evaluation. In addition GLGDGG is currently undertaking a significant piece of work which aims to provide a basis for decision-making and planning future action relating to PHPC in Scotland. Working with a diverse range of stakeholders, a report is being produced which:

- Gathers and synthesizes thinking across a range of diverse but related topics;

- Takes stock of activity, progress and learning across these topics;

- Raises the profile and understanding of PHPC and its importance within Scotland.

The report aims to explore some options and to discuss pros and cons relating to practical next steps which could be taken at a national level to promote more open and supportive attitudes and behaviours relating to death, dying and bereavement in Scotland. Topics considered will include: Compassionate Workplaces; Death Literacy; Funeral Poverty; Education in schools; Compassionate Communities; Wills, Power of Attorney, Advance Directives; Media Awareness Campaigns; Socio-economically Disadvantaged Communities.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported financially by Scottish Government; subscriptions by member organisations of SPPC; Solicitors for Older People Scotland; Cooperative Funeralcare; Brodies LLP.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors are employed by the Scottish Partnership for Palliative Care (SPPC).

References

- Good Life Good Death Good Grief. Available online: www.goodlifedeathgrief.org.uk

- ComRes & National Council for Palliative Care. Dying Matters Coalition - Public Opinion on Death and Dying. April 2016. Available online: http://www.dyingmatters.org/sites/default/files/files/NCPC_Public%20polling%2016_Headline%20findings_1904.pdf

- Scottish Partnership for Palliative Care. Available online: www.palliativecarescotland.org.uk

- Scottish Government. Living and dying well: a national action plan for palliative and end of life care in Scotland. Edinburgh: Scottish Government, 2008.

- Karapliagkou A, Kellehear A. Public Health Approaches to End of Life Care: A Toolkit. National Council for Palliative Care and Public Health England. 2014. Available online: http://www.ncpc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Public_Health_Approaches_To_End_of_Life_Care_Toolkit_WEB.pdf

- Death on the Fringe. Available online: https://deathonthefringe.wordpress.com/about/

- World Health Organisation. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. 1986. Available online: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/index1.html

- Scottish Government. Influencing Behaviours - Moving Beyond the Individual: A User Guide to the ISM Tool. 2013. Available online: http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2013/06/8511/downloads

- Archibald D, Patterson R, Haraldsdottir E, et al. Mapping the progress and impacts of public health approaches to palliative care: a scoping review protocol. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012058. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shucksmith J, Carlebach S, Whittaker V. British Social Attitudes 30: Dying. NatCen Social Research. 2012. Available online: http://www.bsa.natcen.ac.uk/media/38850/bsa_30_dying.pdf

- Rumbold B, Aoun S. Bereavement and palliative care: A public health perspective. Prog Palliat Care 2014.22.

- To Absent Friends. Available online: www.toabsentfriends.org.uk

- Patterson R, Peacock R, Hazelwood M. To Absent Friends, a people’s festival of storytelling and remembrance. Bereavement Care 2017.36.

- Scottish Partnership for Palliative Care. To Absent Friends Activity and Evaluation Report. 2015. Available online: https://www.palliativecarescotland.org.uk/content/publications/1474013863_TAF-evaluation-report-May-2016.pdf

- Scottish Partnership for Palliative Care. It Takes a Village exhibition 2016. Available online: https://www.goodlifedeathgrief.org.uk/content/it-takes-a-village/

- Scottish Government. Active and Healthy Aging - An action plan for Scotland 2014-16. Available online: http://www.jitscotland.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Active-Healthy-Ageing-Action-Plan-final.pdf

- Cohen L, Wimbush E, Myers F, et al. Optimising Older People’s Quality of Life: An Outcomes Framework. Strategic Outcomes Model. NHS Health Scotland. 2014. Available online: http://www.healthscotland.scot/media/1159/optimising-older-people-quality-of-life-strategic-outcomes-model-08-14.pdf

- Health and Sport Committee. We Need to Talk About Palliative Care. SP Paper 836, 15th Report. 2015 (Session 4). Available online: http://www.parliament.scot/parliamentarybusiness/CurrentCommittees/94230.aspx

- Scottish Government. Strategic Framework for Action on Palliative and End of Life Care. 2015. Available online:http://www.gov .scot/Topics/Health/Quality-Improvement-Performance/peolc/SFA

- Scottish Government. Making it Easier - a health literacy action plan for Scotland. 2017. Available online: http://www.gov.scot/Resource/0052/00528139.pdf

- Gillies M. Palliative and End of Life Care in Scotland: The case for a public health approach. Scottish Public Health Network. 2016. Available online: https://www.scotphn.net/projects/palliative-and-end-of-life-care-pelc/palliative-and-end-of-life-care-pelc-2/