Global challenges and initiatives in oncology nursing education

Introduction

Background

Cancer is now the second most common cause of death globally, and as of 2018 accounted for 9.6 million lives lost (1). However, disparities of effective prevention and screening services as well as access to the essential medicines and medical devices and the necessary specialized workforce for effective cancer control are glaring (2), even in high-income countries (HIC) like the US (3). Nevertheless, the cancer burden is expected to rise to 29.4 million in 2040 from 18.1 million in 2018 (4). At least 30% of cancers in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) are caused by infections such as human papilloma virus and hepatitis (1), and tobacco use is responsible for 25% of cancer deaths (1), all factors that qualify cancer as the next global crisis (5).

Effective cancer control requires a multidisciplinary, transversal health workforce coordination and strong policy guidance and action at a government level, with an emphasis on the largest single health workforce globally-nursing. Government-recognized specialized education, scope of practice expansion including advanced nursing pathways, and roles to effectively address all aspects of intervention across the cancer continuum from prevention to survivorship are all necessary.

In 2020, the US government’s Food and Drug Administration approved 57 new anti-cancer medications (6). Together with targeted therapies [e.g., CAR T-cell therapy (7)] and sophisticated supportive care guidelines (8) these advances have accelerated the need for highly specialized nurses capable of patient assessment and nursing practice in technologically dependent and multidisciplinary care and research (e.g., clinical trial) settings worldwide.

Rationale and knowledge gap

Recent oncology nursing education reviews and literature include a survey by the European Oncology Nursing Society [2020] on European cancer nursing education and recognition (9) and a survey on European geriatric oncology nursing education [2021] (10). The first survey had a low response rate (~25%) and the authors found that despite oncology nursing education in some countries beginning as early as the 1980s, only five national governments recognized this specialty. The authors of the second survey described a lack of nurse awareness of the needs of older patients with cancer and ethical concerns of patient over- and under-treatment (10). A survey of global pediatric oncology nursing [129 surveys returned (62%)] that included items on onboarding and continuing education in multiple countries of all income levels) found that regardless of income level, important topics were missing from pediatric oncology nursing onboarding (orientation programs) (11). Only 50% of all respondents had at least 10 hours of continuing education per year. Additional literature has focused on specialty areas such as education on spiritual competency for oncology nurses in China (12), systematic review of oncology nurses’ cancer pain management and need for education from Iran (13), CAR T-cell nursing education in the US (14), and the history and integration of palliative care in oncology nursing in the US (15).

The rationale for this review and knowledge gap it addresses is to provide a historical perspective on the beginnings of oncology nursing specialization, a global review of approaches to oncology nursing education and training over time, and the challenges of creating an adequate oncology nursing workforce in LMICs where the greatest burden lies. It is only recently that these LMICs have been successful at reducing the public health burden of infectious diseases and maternal child health. In many LMICs, governments are addressing the rapidly growing cancer burden using national cancer control plans as a roadmap (https://www.iccp-portal.org/). However, few plans address oncology nursing workforce development, certification standardization, or recognize the need for oncology nursing specialization, advanced nursing roles. In addition, addressing scope of practice limitations, and funding for oncology nursing and faculty training are required for successful cancer control. Thus, the high-level, longitudinal view presented here, highlights aspects of existing literature and programs to provide an integrated summary of the current global actions and solutions to this critical workforce scale-up.

Objective

The objective of this narrative review is to briefly address the global history of oncology nursing specialization, educational interventions, and challenges such as governmental and regulatory factors affecting education and specialization that need to be overcome.

Literature review

Two authors conducted a rapid literature review using Google Scholar, PubMed, and Google (for grey literature) in Spanish and English with date parameters from 2012 to 2022. We searched for seminal articles and novel approaches to oncology nursing education and training, with a focus on efforts in LMIC. The reference lists of selected articles were reviewed for additional relevant literature. Historical oncology nursing data was retrieved from the original references of selected literature.

Strengths and limitations of the manuscript

The manuscript provides a global scope of the history and current status of oncology nursing education rather than regional or national. The authors are familiar with the landscape of education and training in LMICs which facilitated the search for seminal articles. This manuscript includes both pediatric and adult oncology nursing education, which is unusual. Taking a broad approach to not only the challenges but also offering potential solutions based on what is documented in the literature is a strength. The WHO/public health perspective on oncology nursing education is also addressed including social and cultural aspects relevant to local upscaling of the oncology nursing workforce.

We limited our literature search to English and Spanish nursing journals. Given that nurses in many LMICs are overburdened with little protected time for scholarly pursuits such as writing and publishing there are likely issues related to oncology nursing workforce and novel approaches to education and training in LMICs that have not been reported and therefore are missing from this narrative review. Additionally, the landscape of oncology nursing education is rapidly changing. There is a particular need to document on an ongoing basis what is occurring in LMICs with this growing nursing workforce.

Evolution of nursing specialization

In the 1920s, cancer became a leading cause of death in HIC. Disclosure of a cancer diagnosis was unusual, and treatment was limited to surgery and radiation. Most people died of the disease and the nurse’s role was focused on skin care following X-ray therapy, preparing patients for radium implants and providing psychosocial support (16). The explosion of knowledge in the 1970s and beyond in cancer biology and genetics, the myriad treatments, and the increased complexity of care led to the critical need for a specialized, and in some instances a sub-specialized, oncology workforce. Although oncology nursing specialization and sub-specialization began in HICs, it is also occurring in LMICs (see Table 1) (17-20). Nurses caring for individuals with cancer clearly require knowledge and skill beyond that offered in pre-licensure nursing education.

Table 1

| Institution name | Location | Role implemented | Role description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH) Oncology Unit | Blantyre, Malawi | Breast Care Specialist Nurse (BCSN) | Coordinates care, provides staff education and support |

| University College Hospital | Ibadan, Nigeria | Cancer Genetics Counselor (Nurse) | Provides risk assessment and care, including genetic testing standard-of-care, for individuals at increased risk for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer |

| University Cancer Hospital | São Paolo, Brazil | Cardio-oncology Nurse | Assists patients with self-care management and adherence to treatment |

| Ghana College of Nurses and Midwives | Accra, Ghana | Pediatric Oncology Nurse | Lead nursing practice, education and training in pediatric oncology, and leader for future program cohorts |

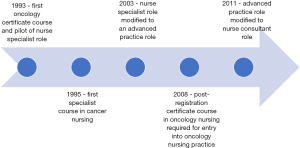

In the US, efforts to integrate cancer content into pre-licensure education began in the mid-1950s; however, these efforts are dependent upon whether there is a faculty member with an expertise in oncology (21). Specialization in oncology with role preparation as a clinical nurse specialist (CNS) at the master’s level began in the late 1960s. The CNS focused on developing hospital nursing staff expertise in caring for cancer patients (22,23). By the late 1990s, many US hospitals eliminated the CNS role (due to cost) and graduate programs shifted to the preparation of the nurse practitioner (NP) (23). Currently, the practice doctorate (DNP) as a single-entry degree for advanced practice is replacing the master’s degree in the US (24). Oncology nurse education and specialization has followed a similar course in other HIC (see Figure 1) (25).

Challenges in oncology nursing education

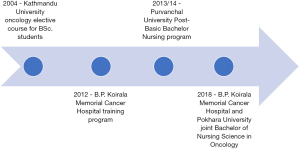

In LMICs, cancer mortality is significantly higher than in HICs and predicted to continue to rise (26). Scaling up of the oncology nursing workforce is critical to meet this patient population, which is already underserved due to multiple factors such as oncology nurse shortages due to migration, lack of professional recognition and perception that oncology nursing is caring only for the dying patient. Scaling up is underway in a number of LMICs such as Nepal (see Figure 2) (27).

There are many challenges to oncology nursing education to create a stable workforce, most importantly human resources, social and cultural factors, and economic factors. We present examples of how these factors influence oncology nursing education globally.

Human resources

Shortage of nurses

The shortage of oncology nurses worldwide reflects the current overall lack of nurses, especially in LMIC settings (28). Recruitment to oncology nursing can be difficult as the specialty is considered emotionally, physically and mentally demanding (29). In addition, migration of nurses trained in oncology from low- to high-income countries due to consistent international recruitment efforts further diminishes the number of specialized nurses available locally and is a loss of the hospital or ministry of health’s investment in oncology nurse training (30). The need for more oncology nurses requires increasing schools of nursing, enhancing oncology content and targeting recruitment to cancer nursing with improved paths to specialization.

Shortage of expert faculty

Across the world, especially in LMICs, nursing faculty with expertise in oncology are scarce (31). Nurses need to be taught by nurses and specialized allied health team members, e.g., pharmacist teaching nurses about pharmacology, rather than physicians with limited knowledge of nursing practice and care. Even in Singapore, a HIC, there aren’t enough locally qualified doctoral-prepared faculty members (32). International nursing academic and research capacity-building collaborations such as the US-based University of Alabama, Turkey and Malawi collaboration in oncology nursing higher education training is one example to address shortages of expert oncology nursing faculty (33).

Social and cultural factors

Stigma

Taboos surrounding cancer and beliefs about treatment have an impact on nurses’ willingness to care for patients with these diseases or specialize in oncology. Nursing students in Turkey were found to have negative attitudes towards caring for patients with cancer finding the experience difficult (34). In an integrative review, Hedenstrom et al. (35) also found that nursing students (and health care professionals) had negative attitudes towards caring for patients with cancer. They recommended mentoring and adding cancer content in pre-licensure curricula to promote nursing student “…positive attitudes while strengthening their knowledge base while increasing experience and confidence in caring for patients with cancer [to] improve quality of care” (p. 6). Significant compassion fatigue for 297 oncology nurses by self-report was found in a study of eight oncology centers in one region in Spain (36). A total of 60% of the nurses had not received any training in managing their emotions and 81% said if faced with the choice of nursing or an alternative profession, they would no longer choose nursing.

Poor perception of nursing profession in some countries

In some countries like Saudi Arabia and Iran, nursing (and oncology nursing), is not considered as a respectable profession for females despite being a top trusted profession (37-39). In Eastern Europe, Armenian nurses perceive they have low status and are not allowed to work independently (40). Sreeja and Nageshwar’s literature search documented that nursing students had mixed feelings about choosing this profession; many believed that nursing offered a positive option to find a government job early, but some saw it as an opportunity to migrate or preferred teaching in the future and had negative feelings towards nursing (41).

Godsey et al. call for a re-branding of nursing and research to re-position nursing to overcome outdated perceptions and confusion of what nurses do and who is a nurse given the variety of educational qualifications and titles (42). This would serve to promote a view of nursing as “…essential to the provision of local, national and global healthcare initiatives” (p. 819).

Economic factors

Cost of specialized education

HIC produce well-prepared nurses who have extensive education and meet competency standards set by various organizations such as European Oncology Nursing Society (EONS), the US-based Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) and Association of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nurses, and the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology (CANO/ACIO). Many other countries have formulated educational modules for specialization along with continuous oncology nursing education to enhance nursing knowledge and skills, e.g., Pakistan (43), Ghana, Bangladesh and Guatemala (44). However, challenges of financial constraints and a lack of sustainability threaten these nascent oncology educational initiatives, which are generally funded by grants or international partners instead of governments.

Despite the earlier lack of scholarship opportunities for LMIC nurses to obtain higher education and conduct clinical research worldwide, there are new initiatives to achieve this goal. For example, in Rwanda (45), the University of Global Health Equity in Butaro, aligned with the Butaro Cancer Center of Excellence, offers oncology nurses advanced education with some scholarship support from the government (46).

Salary

Oncology patients are often taken care of by general nurses. Specialty salaries can attract nurses to sub-specialty clinical areas (47). Many nurses choose to work in intensive care areas or cardiac units due to lucrative salaries compared to oncology (e.g., in Pakistan), since oncology as a specialty is unrecognized by ministries of health or education in many countries (48). Low salaries and a lack of specialty acknowledgment by the government leads to high rate of turnover and increase in burnout in the complex oncology nursing care setting (49). Nevertheless, the World Health Organization (WHO) Strategic Plan for Nursing & Midwifery (50) calls on governments to “Recognize the educational advancement of midwives and nurses with corresponding role responsibilities and related remuneration” (p. 14).

Summary

There are disparities worldwide in oncology nursing education. Regardless of the income-status of the country, the quality of this specialty education varies. Human resources may be severely restricted, e.g., Pakistan has less nurses than doctors (51), which makes it even harder to recruit and retain nurses in complex care areas such oncology. Social and cultural factors impact how nurses understand their role and position in society. Myths about cancer contagion and personal risks to the nurse diminish nursing willingness to become specialized and work in cancer care. Economic challenges will only be addressed when governments include oncology nursing special care allowances as they do now for other specialty care nurses.

Existing educational interventions

There is a lack of oncology content in the pre-licensure nursing curricula across the globe, whether in Africa (52), the Americas (in Brazil only 1/3 of public institutes include oncology in the curriculum) (53), Southeast Asia, Europe, Eastern Mediterranean, or in the Western Pacific. A survey of nine Balkan and Middle East countries found that Israel, Slovenia, and Greece had fairly substantial oncology nursing education programs, while other countries, especially in the Balkans, offered none at all (54). A variety of educational interventions have been undertaken to compensate for this and to strengthen the existing oncology nursing workforce, including pre-licensure courses, oncology intensives, certificate programs, diploma programs, as well as North-North and North-South collaborations. Some of these are described below.

Pre-licensure oncology nursing courses are delivered as an elective or as content embedded into existing courses, or clinical opportunities designed to either recruit undergraduates to the oncology specialty or to strengthen their oncology clinical expertise (55). Educators also have designed and implemented prelicensure on-line courses to help bridge the gap between new graduate competence and their ability to practice in the oncology specialty area. One such course, developed in the US, is delivered asynchronously over 15 weeks and includes six units utilizing a variety of active teaching strategies such as discussions, role-plays, case studies, and virtual simulations but does not include a clinical component (56).

Oncology Intensives focused on experienced nurses who have limited education and training in caring for patients with cancer also have been implemented by hospitals to improve care. These efforts range from a “boot camp” that combines a one-day didactic class focused on chemotherapy administration and oncologic emergencies with a 4-hour simulation (57) to a 4-week South-South residential pediatric oncology nurse educator training in Chile for nurse educators from across Latin America (58), to a 16-week oncology nurse fellowship program developed to address the shortage of qualified staff to fill vacancies. This 16-week program included education sessions, observational experiences in a variety of areas and assignment to a preceptor who provided guidance and support to the nurse fellow throughout the program (59).

Certificate Programs in oncology nursing also have been developed to enhance the knowledge and skill of practicing nurses. This broad term encompasses two types of programs—those developed by the employer or hospital system that awards a certificate of completion and those developed by or in collaboration with a university that award a certification recognized by a regulatory body such as the ministry of health or board of nursing. An example of the former is a one-month program developed by the Apollo Hospitals Group in New Delhi, India. It includes didactic lectures about cancers commonly seen at the Apollo, traditions, taboos and cultural beliefs of the patient population. Presenters included consultants (physicians, surgeons), nurses, social workers and other members of the health care team (60). An example of the latter is a national education program in pediatric oncology nursing developed through a collaboration between the University of Gothenburg and the Swedish Childhood Cancer Foundation. This 2.5-year, 45 credit program led to a certificate in pediatric oncology nursing. The program consisted of four sections and each section began with a week of lectures and group discussions and ended with an exam. Nurses continued to work in their departments while enrolled in the program (61).

Certificate programs differ from professional oncology nursing certification programs established by specialty organizations such as the US-based Oncology Nursing Society and Association of Pediatric Hematology Oncology Nurses through the Oncology Nursing Certification Corporation, an affiliate of the Oncology Nursing Society. Certification was developed to assure and safeguard consumers and requires 2,000 hours of practice prior to taking an examination.

Diploma Program for Oncology Nursing. A North-South partnership among three institutions—Princess Margaret Cancer Center, the Aga Khan University School of Nursing and Midwifery, and the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital—resulted in the development of a diploma program for oncology nursing education. Approved by the Nursing Council of Kenya, this program led to the recognition of the specialty in the country (62). Sixteen modules delivered over an 18-month period combine work with education. The aim is to educate nurses to function as specialized oncology nurses who can advance cancer care across the illness trajectory by providing safe, competent, compassionate and quality cancer care. The program is based on the Canadian Association of Nurses in Oncology (CANO/ACIO) standards and competencies for the specialist oncology nurse adapted to contextual relevance (62).

Oncology nursing curriculum development

Curriculum development must consider several factors including national scope and standards of professional nursing practice, and the nurse practice act or national legal and regulatory frameworks (rules and regulations) for the country’s nursing profession. Consideration must be given to the evolution of the specialty of oncology nursing—whether it is an emerging, evolving or established specialty (63). Government recognition of the specialty can determine whether there are country-specific oncology specialty scope and standards upon which to build the curriculum and include in the national cancer control plan. Professional nursing associations play an important role by developing scope and standards of professional nursing practice if none exists, assisting with the formation or evolution of specialty practice, and advocating for the education of a nursing workforce able to meet every country’s growing cancer burden (see Table 2) (64-68).

Table 2

| Nursing organization | Document title | URL |

|---|---|---|

| Canadian Association of Nurses In Oncology/Association canadienne des infirmieres en oncologie (CANO/ACIO) | Practice Standards and Competencies for the Specialized Oncology Nurse | https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.cano-acio.ca/resource/resmgr/standards/CONEP_Standards2006September.pdf |

| The European Oncology Nursing Society (EONS) | The EONS Cancer Nursing Education Framework | https://cancernurse.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/EONSCancerNursingFramework2018-1.pdf |

| European School of Oncology-European Oncology Nursing Society (ESO-EONS) | Masterclass in Oncology Nursing | https://cancernurse.eu/education/eso-eons-masterclasses-and-eso-e-sessions/ |

| Oncology Nursing Society | Core Curriculum for Oncology Nursing | https://www.ons.org/books/core-curriculum-oncology-nursing-sixth-edition |

| Royal College of Nursing | Career Pathway and Education Framework for Cancer Nursing | https://www.rcn.org.uk/Professional-Development/publications/career-pathway-and-education-framework-for-cancer-nursing-uk-pub-010-076 |

Competency-based education

Core competencies identify what is needed to fulfill nursing responsibilities. They provide the foundation for curriculum development and clinical practice experiences (63) Competency is demonstrated by the nurse in the clinical setting through providing care that integrates knowledge learned and skills mastered (69).

Addressing culture, resources, and practice norms

An oncology nursing curriculum that is context specific and relevant to diseases prevalent in the country and informed by the national cancer control plan is key to successfully managing national and regional cancers. The specific cancer burden and priorities across the world is not uniform. For example, esophageal cancers are common in northern China, Iran, southern Africa, and India, but uncommon in Central America, and Northern and Western Africa (70,71); therefore, the curriculum in these countries should reflect that. Content areas addressing patient and family issues include disclosure of diagnosis/prognosis, communication, decision-making, psychosocial, and sexuality need to consider the country’s existing cultural norms. While nursing school curricula are designed to prepare global citizens of nursing able to provide care in a myriad of national settings, in specialties such as oncology in settings with limited resources, it would be rational to focus on preparing nurses to care for the patients they are going to care for in their setting. This means recognizing the epidemiology of cancer in the country where they are licensed to practice as well as the region in which they live. This also requires awareness of cultural norms of nursing scope of practice by law and tradition, such as diagnosis disclosure by nurses, or how end-of-life pain control is managed. Oncology nursing best practices from high-income countries are not always permitted by law, acceptable to patients and families, or appropriate in all countries. This should be acknowledged and addressed when scaling up oncology nursing education.

The curriculum must include a clinical component based upon country resources, cultural context, and be inclusive of accepted traditional medicines and practices. Nursing interventions must consider available medications and devices and ideally be based on evidence locally generated. Support (including financial and protected time) must be provided to develop local nurse scientists who can lead curriculum and training efforts as well as local nurse educators.

North-south and south-south collaborations

If existing internationally available standards and curricula are utilized, they need to be adapted, not adopted outright, to the country or region. Successful examples include the redesign of the Canadian Specialized Oncology Nursing Education Program (SONE) for the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, specifically Qatar (72) and the adaption of the CANO/ACIO standards to regional (East African) needs and context (62). Curricula that are developed through North-South collaborations should be based on results of a learning needs assessment, include relevant content, competency assessment, longitudinal evaluation, and a plan to ensure sustainability (73).

Teaching methodologies

Adult health workforce teaching strategies vary widely across the globe. It is critical that teaching approaches for oncology nurses match learner expectations while also introducing newer technologies and instruction innovations as resources permit (e.g., virtual reality, simulation laboratories). During didactic education, a dependence on passive learning (teacher-centered) methodologies results in more limited learning but promotes active listening and attention to create retention (74). Active methodologies (learner-centered) such as case discussions and role play that avoid long lectures and an over-reliance on PowerPoint slides demand that “students think, discuss, challenge, and analyze information…[and] encourages conversation and debate” (74).

Learning objectives

The learning objectives should dictate the teaching methodology. Learning objectives describe the knowledge the nurse learner will have and the skills to be able to perform following the educational intervention (75).

Educational activities

Educational teaching strategies include demonstrations in a simulation lab, or using mannequins, virtual reality training, supervised instruction in the clinical setting, in vivo demonstrations, case studies, peer teaching opportunities, brainstorming for problem solving and round table discussions. Important nursing topics such as patient/family education and communication techniques require role plays.

Learning to deliver patient/family education

Collaboration with local adult health education specialists at universities or medical centers improves cultural relevance and efficacy of knowledge and skill sharing. A major part of nursing practice is teaching patients and families and this skill must be taught since the patient and/or parents may or may not speak the local language, differ in education levels, are often distressed by the cancer diagnosis and find it hard to concentrate or learn in specific ways.

Preceptors

Preceptor training includes coaching, positive feedback, follow-up, ongoing skill assessment beginning with patient assessment (both psychosocial, spiritual and physiological). Preceptors who are expert oncology nurses and can provide positive oncology specialization clinical training are essential to all oncology nursing education. These preceptors must be identified and given adult education training to gain the teaching skills necessary for initial demonstration and education, continual positive feedback and assessment of the oncology nurse learner, both in the classroom and in the clinical setting. A recent integrative review about initiating and sustaining a clinical nurse preceptor program initiation recommends preparation for the role using an “evidence-based, standardized curriculum that features diverse teaching modalities, critical thinking, and clinical reasoning…[followed by] ongoing education, training, and support to improve nursing satisfaction, retention, and the quality of nursing care.” (76).

Learner evaluation

Evaluation of the practice based on the identified competencies that are foundational to the curriculum is critical. Evaluation should be longitudinal to ensure knowledge and skill retention, implementation in practice in compliance with local practice standards. While the pre-test/post-test evaluation is ubiquitous throughout nursing education, it is insufficient to measure long-term retention, practice implementation, and improved patient outcomes. Alternative evaluation strategies have been recommended by professional associations such as the Ambulatory Oncology Nurse Quality Consortium (77).

Overcoming challenges: potential solutions

Overcoming economic and human resource challenges

One economic challenge related to the workforce shortage of nurses including oncology nurses is the cost of education. An effective solution has been support for oncology nursing education by non-profits and/or the country’s government. Examples include the American Cancer Society professorships and scholarships, International Union Against Cancer (UICC) fellowships, US National Cancer Institute training grants, and the Malawi government support for a Masters degree (16,23,52). The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the usefulness of technology for education with many schools transitioning to online learning. The shortage of qualified faculty can be addressed by harnessing technology to employ virtual or distant learning augmented by onsite clinical preceptorship (73).

Social and cultural

Strategies to overcome the public’s poor perception of the nursing profession and to raise the status and profile of nurses must come from the media, hospital administration, governments, industry and the profession itself. The media’s positive portrayal of nurses may help to change public’s poor perception of nursing (78) as well as serve to recruit individuals to the profession. Nurse managers and hospital administrators can create a respectful work environment which significantly affects nurses’ intention to remain (79). Government efforts such as the creation of the European Higher Education Area led to nursing education shifting from diploma to degree programs and to most countries offering postgraduate and doctoral nursing degrees. These efforts will strengthen professionalism and provide expanded opportunities for nurses (80). “The elimination of negative expectations can be facilitated by a system of measures to improve the regulation, organization and remuneration of nurses, improve the quality of professional training of nurses, taking into account their new role, as well as the social prestige of this professional group” (81).

The global “Nursing Now” campaign (www.nursingnow.org), the US-based “Nurses Rise to the Challenge Every Day” campaign and the global Center for Health Worker Innovation (nursing.jnj.com) are examples of large-scale efforts to promote nursing. The “Nursing Now” initiative was launched by the Burdett Trust for Nursing in collaboration with the International Council of Nurses and the World Health Organization is an example of what the profession is doing to raise the status and profile of nursing. Johnson & Johnson’s “Nurses Rise to the Challenge Every Day” campaign is an example of industry efforts and part of this company’s long-standing commitment to the profession.

Studies have found that nurses are reluctant to specialize in oncology as they perceive it to be depressing. A novel 3.5-day program for undergraduates enrolled in a 3-year degree course in the UK was successful in improved attitudes, knowledge, and confidence in cancer care delivery (82). An especially innovative aspect of the program was on cancer as a life-altering long-term condition with presentations given by patients, caregivers and clinicians. Another innovative intervention to address this challenge was a randomized control trial with 220 nursing students in Spain. Students were shown movie clips of patients with cancer and sometimes dying as a simulation exercise to experience the emotional impact of caring for patients with cancer and watching the human responses in the films to improve their clinical judgment and decision making and reduce their anxiety about working in oncology (83).

Governments

Government transition to a public health approach to cancer control in many countries has led to scope of practice changes and to national cancer control planning that often (but not yet always) addresses areas important to nursing such as workforce capacity-building and occupational hazards. Governments are also informed by agencies like the WHO for guidance on health workforce, e.g., Global Strategic Directions for Nursing and Midwifery 2021–2025 (50), and cancer control, Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer technical package (84) and WHO Cancer Report (85). Although not specifically addressing oncology nursing, these documents address key topics in oncology education and specialization, e.g., competency-based, quality standards, and meet national priorities and population health needs knowledge and attitudes, while cautioning super-sub-specialization and unbalanced allocation of the health workforce.

Conclusions

In this paper, we briefly present the history of oncology nursing specialization, highlighting the importance of specialized oncology nurses for safe patient care and best possible outcomes. Challenges and solutions (proposed and implemented) to oncology nursing education globally are identified. Multiple examples of existing educational interventions are described from regions with varying resource levels. Specific attention is given to oncology nursing curriculum development including teaching methodologies and evaluation. We highlight the importance of a competency-based curriculum in concordance with the country’s resources and propose effective teaching, learning and evaluation strategies. Considerations to addressing challenges in oncology nursing education are summarized. The information presented here is intended to inform future development of oncology nursing education programs and interventions worldwide.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Margaret Fitch and Annie Young) for the series “Oncology Nursing” published in Annals of Palliative Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-1120/coif). The series “Oncology Nursing” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- World Health Organization. Cancer: Key Facts Geneva2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/cancer#tab=tab_1

- World Health Organization. Partnering to improve the quality of cancer care: WHO teams up with the world's leading organization for physicians and oncology professionals 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/04-06-2022-partnering-to-improve-the-quality-of-cancer-care-who-teams-up-with-the-worlds-leading-organization-for-physicians-and-oncology-professionals

- Winkfield KM, Winn RA. Improving Equity in Cancer Care in the Face of a Public Health Emergency. Cancer J 2022;28:138-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. The Cancer Atlas: The Burden of Cancer 2022. Available online: https://canceratlas.cancer.org/the-burden/the-burden-of-cancer/#:~:text=In%202040%2C%20an%20estimated%2029.4,based%20solely%20on%20demographic%20changes

- World Economic F. Cancer: how to stop the next global health crisis 2022 [updated January 19 2022. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/01/cancer-health-crisis-oncology-astrazeneca/

- Olivier T, Haslam A, Prasad V. Anticancer Drugs Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration From 2009 to 2020 According to Their Mechanism of Action. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2138793. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al-Sukhun S, de Lima Lopes G Jr, Gospodarowicz M, et al. Global Health Initiatives of the International Oncology Community. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2017;37:395-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Campbell C, Nowell A, Karagheusian K, et al. Practical innovation: Advanced practice nurses in cancer care. Can Oncol Nurs J 2020;30:9-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crombez P, Sharp L, Ullgren H, et al. CN10 cancer nursing education and recognition in Europe: a survey by the European oncology nursing society. Ann Oncol 2020;31:S1127. [Crossref]

- Puts M, Oldenmenger WH, Haase KR, et al. Optimizing care for older adults with cancer: International Society of Geriatric Oncology Nursing and Allied Health Interest Group and European Oncology Nursing Society survey results from nurses regarding challenges and opportunities caring for older adults with cancer. J Geriatr Oncol 2021;12:971-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morrissey L, Lurvey M, Sullivan C, et al. Disparities in the delivery of pediatric oncology nursing care by country income classification: International survey results. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2019;66:e27663. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu Y, Jiao M, Li F. Effectiveness of spiritual care training to enhance spiritual health and spiritual care competency among oncology nurses. BMC Palliat Care 2019;18:104. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bouya S, Balouchi A, Maleknejad A, et al. Cancer Pain Management Among Oncology Nurses: Knowledge, Attitude, Related Factors, and Clinical Recommendations: a Systematic Review. J Cancer Educ 2019;34:839-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor L, Rodriguez ES, Reese A, et al. Building a Program: Implications for Infrastructure, Nursing Education, and Training for CAR T-Cell Therapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2019;23:20-6. [PubMed]

- Chow K, Dahlin C. Integration of Palliative Care and Oncology Nursing. Semin Oncol Nurs 2018;34:192-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lusk B. Prelude to specialization: US cancer nursing, 1920-50. Nurs Inq 2005;12:269-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brown ER, Bartlett J, Chalulu K, et al. Development of multi-disciplinary breast cancer care in Southern Malawi. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2017;26:e12658. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adejumo PO, Aniagwu TIG, Awolude OA, et al. Feasibility of genetic testing for cancer risk assessment programme in Nigeria. Ecancermedicalscience 2021;15:1283. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Costa IBS, Bittar CS, Fonseca SMR, et al. Brazilian cardio-oncology: the 10-year experience of the Instituto do Cancer do Estado de Sao Paulo. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 2020;20:206. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shepherd K, Morrissey L, Hollis R, et al. The Ghanaian Pediatric Oncology Nursing Program Promotes Nursing Clinical Expertise and Leadership. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2021;68:S117-8.

- Watson HG, Keeling DM, Laffan M, et al. Guideline on aspects of cancer-related venous thrombosis. Br J Haematol 2015;170:640-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kerr H, Donovan M, McSorley O. Evaluation of the role of the clinical Nurse Specialist in cancer care: an integrative literature review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2021;30:e13415. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mooney KH. Oncology nursing education: peril and opportunities in the new century. Semin Oncol Nurs 2000;16:25-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Griffith D. DNP vs PhD: The practice Doctorate emerges as most popular choice for NPs 2022. Available online: https://canpweb.org/resources/connections-newsletter/2021-editions/connections-march-2021/dnp-vs-phd-the-practice-doctorate-emerges-as-most-popular-choice-for-nps/#:~:text=There%20are%20366%20DNP%20programs,at%20a%202021%20AACN%20conference

- Mak SS. Oncology Nursing in Hong Kong: Milestones over the Past 20 Years. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2019;6:10-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah SC, Kayamba V, Peek RM Jr, et al. Cancer Control in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Is It Time to Consider Screening? J Glob Oncol 2019;5:1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sharma S. Development of oncology nursing in Nepal: Historical perspective. Nepalese Journal of Cancer 2020;4:18-23. [Crossref]

- World Health Organization. State of the World’s Nursing Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240003279

- Mazzella-Ebstein AM, Tan KS, Panageas KS, et al. The emotional intelligence, occupational stress, and coping characteristics by years of nursing experiences of newly hired oncology nurses. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2021;8:352-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thompson M, Walton-Roberts M. International nurse migration from India and the Philippines: the challenge of meeting the sustainable development goals in training, orderly migration and healthcare worker retention. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 2019;45:2583-99. [Crossref]

- Bialous SA. Vision of Professional Development of Oncology Nursing in the World. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2016;3:25-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chua GP. Challenges Confronting the Practice of Nursing in Singapore. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2020;7:259-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walker DK, Edwards RL, Bagcivan G, et al. Cancer and Palliative Care in the United States, Turkey, and Malawi: Developing Global Collaborations. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2017;4:209-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kapucu S, Bulut HD. Nursing Students' Perspectives on Assisting Cancer Patients. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 2018;5:99-106. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hedenstrom ML, Sneha S, Nalla A, et al. Nursing Student Perceptions and Attitudes Toward Patients With Cancer After Education and Mentoring: Integrative Review. JMIR Cancer 2021;7:e27854. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arimon-Pagès E, Torres-Puig-Gros J, Fernández-Ortega P, et al. Emotional impact and compassion fatigue in oncology nurses: Results of a multicentre study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2019;43:101666. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wazqar DY. Oncology nurses' perceptions of work stress and its sources in a university-teaching hospital: A qualitative study. Nurs Open 2018;6:100-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roshangar F, Soheil A, Moghbeli G, et al. Iranian nurses' perception of the public image of nursing and its association with their quality of working life. Nurs Open 2021;8:3441-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Darbyshire P, Thompson DR. Can nursing educators learn to trust the world's most trusted profession? Nurs Inq 2021;28:e12412. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sahakyan S, Akopyan K, Petrosyan V. Nurses role, importance and status in Armenia: A mixed method study. J Nurs Manag 2020;28:1561-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sreeja Nageshwar V. Public Perception of nursing as a profession. International Journal for Research in Applied Sciences and Biotechnology 2018;5:15-9. (IJRASB). [Crossref]

- Godsey JA, Houghton DM, Hayes T. Registered nurse perceptions of factors contributing to the inconsistent brand image of the nursing profession. Nurs Outlook 2020;68:808-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ashraf MS. Pediatric oncology in Pakistan. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2012;34:S23-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karim S, Sunderji Z, Jalink M, et al. Oncology training and education initiatives in low and middle income countries: a scoping review. Ecancermedicalscience 2021;15:1296. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Uwayezu MG, Nikuze B, Fitch MI. A focus on cancer care and the nursing role in Rwanda. Can Oncol Nurs J 2020;30:223-6. [PubMed]

- Uwayezu MG, Sego R, Nikuze B, et al. Oncology nursing education and practice: looking back, looking forward and Rwanda’s perspective. Ecancermedicalscience 2020;14:1079. [PubMed]

- Motsosi KS, Rispel LC. Nurses' perceptions of the implementation of occupational specific dispensation at two district hospitals in the Gauteng Province of South Africa. Africa Journal of Nursing and Midwifery 2012;14:130-44.

- So W, Cummings G, Calvo L, et al. Enhancement of oncology nursing education in low- and middle-income countries: Challenges and strategies. Journal of Cancer Policy 2016;8. [Crossref]

- Bonetti L, Tolotti A, Valcarenghi D, et al. Burnout precursors in oncology nurses: a preliminary cross-sectional study with a systemic organizational analysis. Sustainability 2019;11:1246. [Crossref]

- World Health Organization. Global strategic directions for nursing and midwifery 2021-2025 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033863.

- Yaqoob A. A vision for nursing in Pakistan: is the change we need possible? Br J Nurs 2020;29:70-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bingo S. What is the Role of the Oncology Nurse Leader in Building Oncology Nursing Capacity in Malawi? Clin J Oncol Nurs 2020;24:215. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aguiar BRL, Ciol MA, Simino GPR, et al. Oncology teaching in undergraduate nursing at public institutions courses in Brazil. Rev Bras Enferm 2021;74:e20200851. [PubMed]

- Savopoulou G. Undergraduate oncology nursing education in the Balkans and the Middle East. J Cancer Educ 2001;16:139-41. [PubMed]

- Lockhart JS, Oberleitner MG, Fulton JS, et al. Oncology Resources for Students Enrolled in Pre-Licensure and Graduate Nursing Programs in the United States: A Scoping Review of the Literature. Semin Oncol Nurs 2020;36:151026. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cazeau N, Kaur T. A Survey of Clinicians Evaluating an Online Prelicensure Oncology Nursing Elective. Semin Oncol Nurs 2021;37:151141. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bagley KA, Dunn SE, Chuang EY, et al. Nonspecialty Nurse Education: Evaluation of the Oncology Intensives Initiative, an Oncology Curriculum to Improve Patient Care. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2018;22:E44-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sullivan CE, Segovia Weber L, Viveros Lamas P, et al. A sustainable model for pediatric oncology nursing education and capacity building in Latin American hospitals: Evolution and impact of a nurse educator network. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2021;68:e29095. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balentine S, Quigley V. The Oncology Nursing Fellowship Program: A Pipeline for the Future. Oncology Issues 2016;31:34-44. [Crossref]

- Banerjee CU, Sen MB, Girdar MR, et al. Effectiveness of Certificate Program on Oncology Nursing. 2019.

- Pergert P, Af Sandeberg M, Andersson N, et al. Confidence and authority through new knowledge: An evaluation of the national educational programme in paediatric oncology nursing in Sweden. Nurse Educ Today 2016;38:68-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McQuestion M, Mushani T, Booker R, et al. Looking within and beyond our borders: Exemplars of international initiatives involving CANO/ACIO members. Can Oncol Nurs J 2021;31:339-44. [PubMed]

- American Nurses Association. American Nurses Association Recognition of a Nursing Specialty, Approval of a Specialty Nursing Scope of Practice Statement, Acknowledgment of Specialty Nursing Standards of Practice and Affirmation of Focused Practice Competencies. 2017.

- Canadian Association of Nurses In Oncology/Association canadienne des infirmieres en oncologie (CANO/ACIO). Practice Standards and Competencies for the Specialized Oncology Nurse. 2006. Accessed March 28, 2023.

- The European Oncology Nursing Society (EONS). The EONS Cancer Nursing Education Framework. 2018. Accessed March 28, 2023.

- The European School of Oncology-The European Oncology Nursing Society (ESO-EONS). Masterclass in Oncology Nursing. 2023. Accessed March 28, 2023.

- Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) (Editor). Brant JM, Cope DC, Saria MG, eds. Core Curriculum for Oncology Nursing. 7th ed. Elsevier. Forthcoming. 2023.

- Royal College of Nursing. Career Pathway and Education Framework for Cancer Nursing. 2022. Accessed March 28, 2023.

- Fukada M. Nursing Competency: Definition, Structure and Development. Yonago Acta Med 2018;61:1-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang J, Koulaouzidis A, Marlicz W, et al. Global Burden, Risk Factors, and Trends of Esophageal Cancer: An Analysis of Cancer Registries from 48 Countries. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:141. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics for Esophageal Cancer 2022. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/esophagus-cancer/about/key-statistics.html

- Martina K, Ghadimi L, Julius A, et al. Redesigning and implementing a Canadian oncology nursing curriculum for an international partnership. Can Oncol Nurs J 2019;29:242-6. [PubMed]

- Taj M, Ukani H, Lalani B, et al. Blended Oncology Nursing Training: A Quality Initiative in East Africa. Semin Oncol Nurs 2022;38:151299. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Russell K. Active vs Passive Learning: What’s the Difference: Graduate Programs for Educators; 2021. Available online: https://www.graduateprogram.org/2021/06/active-vs-passive-learning-whats-the-difference/#:~:text=Active%20learning%20is%20learner%2Dcentered,%2C%20consider%2C%20and%20translate%20information

- Chatterjee D, Corral J. How to Write Well-Defined Learning Objectives. J Educ Perioper Med 2017;19:E610. [PubMed]

- Smith LC, Watson H, Fair L, et al. Evidence-based practices in developing and maintaining clinical nurse preceptors: An integrative review. Nurse Educ Today 2022;117:105468. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beaver C, Magnan MA, Henderson D, et al. Standardizing Assessment of Competences and Competencies of Oncology Nurses Working in Ambulatory Care. J Nurses Prof Dev 2016;32:64-73; quiz E6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abbas S, Zakar R, Fischer F. Qualitative study of socio-cultural challenges in the nursing profession in Pakistan. BMC Nurs 2020;19:20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muchlis N, Amir H, Cahyani DD, et al. The cooperative behavior and intention to stay of nursing personnel in healthcare management. J Med Life 2022;15:1311-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manzano-García G, Ayala-Calvo JC. An overview of nursing in Europe: a SWOT analysis. Nurs Inq 2014;21:358-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aleksandrova OA, Nenakhova YS, Yarasheva AV. Transformation of Russian healthcare: the role of nurses. Probl Sotsialnoi Gig Zdravookhranenniiai Istor Med 2021;29:1251-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edwards D, Anstey S, Kelly D, et al. An innovation in curriculum content and delivery of cancer education within undergraduate nurse training in the UK. What impact does this have on the knowledge, attitudes and confidence in delivering cancer care? Eur J Oncol Nurs 2016;21:8-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Raga Chardi RM. The cinema as an educational strategy in the acquisition of skills in the formation of the nursing degree. University of Malaga; 2016.

- World Health Organization. CureAll framework: WHO Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer: increasing access, advancing quality, saving lives. 2021. Report No.: 9240025278. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240025271

- World Health Organization. WHO Report on Cancer. Geneva; 2021. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1267643/retrieve