The pursuit of goal-concordant surgical care: persistent challenges and potential for progress

Introduction

Surgical patients have significant palliative care needs, but evidence characterizing and evaluating palliative care interventions in surgery is limited (1,2). In 2016, Lilley et al. identified critical gaps in the literature and subsequently detailed several research priorities for palliative care in surgery: measuring outcomes that matter to patients, communication and decision making, and delivery of palliative care to surgical patients (2,3). In a recent study, Kopecky et al. review 22 studies relating to palliative care for seriously ill surgical patients published since 2016 (4). The authors highlight progress across several domains outlined by Lilley et al., but also identify a notable exception: no publications directly addressed alignment of surgical care with patient-oriented outcomes.

Goal concordance has been called the “holy grail” of serious illness care, a characterization indicating both its significance and elusiveness as an object of measurement (5). The lack of an accepted standard for measuring goal concordance reflects significant methodological challenges and is a barrier to establishing evidence-based interventions to align care with patients’ priorities. Although attention to this problem is growing, conceptual models and approaches to measuring goal concordance have largely focused on non-surgical patients (5-7). In the following editorial, we summarize proposed methods for measuring goal concordance, review challenges of applying these frameworks to surgical patients, and discuss potential trajectories for progress in the measurement of goal-concordant surgical care.

Existing methods for assessing goal concordance

All existing methods for measurement of goal-concordant care have limitations (6,7). Eliciting reports from patients or surrogates as to whether care aligned with patients’ priorities is intuitive, but may overestimate goal concordance because of recall bias, social desirability bias, selective memory, or post hoc rationalization of prior decisions (6,7). Similar issues complicate attempts to assess alignment of care with patients’ priorities by surveying caregivers after a patient’s death (8).

Use of large datasets to assess patterns of treatment and resource utilization avoids biases associated with patient or caregiver reports, but requires assumptions about patient goals and the appropriateness of specific treatments. These methods may highlight potential areas of discordance (e.g., hospitalizations among hospice patients), but are unable to detect when utilization may actually serve patients’ goals because of specific circumstances (e.g., when hospitalization is for complex symptom management), unique preferences, or evolving priorities (6,7). Population-level assessments do not offer insight into whether care is aligned with patient preferences in individual cases.

A more patient-centered approach might be to compare the care a patient received to their documented preferences (5-7). Because it draws on information from the medical record, this longitudinal assessment enables more detailed consideration of what treatments were delivered and whether they aligned with documented goals. However, there are several challenges associated with this approach. First, documentation of patients’ preferences may be absent or insufficient to inform subsequent assessments of goal concordance. Second, patients’ goals may change over time. Third, it may not be clear which of several documented goals were of highest priority to the patient when real clinical circumstances placed them in conflict (5-7). And finally, assessments of whether the care delivered was likely to achieve desired outcomes are complex and likely to vary across providers (9).

Challenges associated with assessing goal concordance in surgical patients

These problems are particularly formidable when assessing goal concordance in seriously ill surgical patients (2). Evidence suggests that although surgeons acknowledge the importance of advance care planning, its completion and documentation is inconsistent. For example, a recent study found that more than half (66%) of patients did not have an advance directive on file prior to major surgery (10). In many cases, assessment of patients’ baseline preferences may therefore be impossible.

In addition, seriously ill surgical patients’ clinical trajectories are often more complex than those of medical patients with progressive terminal illness, and may include tradeoffs between competing priorities, complications resulting in escalations of care or further procedures, and an evolving calculus of what goals are realistically achievable (2). Because patients prioritizing comfort may opt for surgical interventions aimed at improving quality of life, patient-centered outcome measures should incorporate expected setbacks associated with surgical recovery (e.g., pain and increased care needs) and distinguish between those that are acute versus those that become chronic (2). More significant setbacks (e.g., postoperative complications) may result in escalations of care, fluctuating assessments of what goals appear achievable, and real-time rebalancing of priorities (2,11). Attempts to scrutinize appropriateness of acute surgical care solely through the lens of previously documented directives may yield invalid judgments of whether care was aligned with patients’ priorities.

These characteristics of surgical care suggest that its appropriateness should be judged not only by the outcomes it produced, but also by the likelihood that the care delivered would achieve a desired result (2). Otherwise, inability to achieve a desired outcome because of unexpected intraoperative findings or postoperative complications would yield a judgment of goal discordance, even if decisions were made in a patient-centered manner based on the best information and expertise available. Some have argued that expectations of likely outcomes are too subjective and variable to serve as a basis for measurement of whether care aligned with patients’ goals (5). This is a serious problem compounded by the paucity of data describing patient-centered outcomes following surgery (2,12). Rather than forgoing judgment of likely outcomes, however, it might be desirable to strengthen these assessments with evidence.

Relationship between palliative care priorities and assessing goal concordance

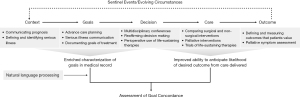

Despite the challenges associated with measurement of goal-concordant surgical care, progress in other palliative care domains may support the assessment of goal concordance via two mechanisms: enriching the characterization of patients’ goals and decision making in the medical record and informing evaluation of whether the care delivered aligned with those goals (Figure 1).

Lee et al.’s list of quality indicators for surgical palliative care states that in the preoperative period, surgical deliberations should include discussion of the goals of surgery, the patient’s prognosis, and the patient’s “priorities, values, and preferences regarding treatment options (including surgical and nonsurgical options)” (11). Discussion of life-sustaining therapies in the perioperative period is also essential, specifically the circumstances that might necessitate their use and their associated limitations (11). Similar priorities are outlined in the American College of Surgeons’ Geriatric Surgery Verification (GSV) Program Standards for Goals and Decision Making (Standards 5.1-5.5), which mandates documentation of “a verbatim quote by the patient about his or her overall health and treatment goals” and “attestation that the surgeon has discussed the anticipated impact of both surgical and non-surgical treatments on symptoms, function, burden of care, living situation, and survival” (12). Recent evidence summarized by Kopecky et al. suggests perioperative palliative care consultation may be an effective mechanism for achieving these objectives and improving documentation of patients’ preferences in the medical record (13,14).

Recent advances in surgical communication also reflect a shift towards serious illness communication, which has been affirmed as a basis for delivering goal-concordant care (15). Cooper et al. established a framework that directs surgeons to contextualize acute surgical conditions in the context of underlying illness, elicit goals and priorities, present treatment options, and orient care to achieving those goals while also considering time-limited trials of additional therapies in cases of clinical uncertainty (16). Use of the “Best Case/Worst Case” tool also appears helpful in guiding complex surgical decision making regarding high-risk interventions (17,18). These innovations have the potential to improve the quality of available information regarding patients’ goals and priorities.

In order to facilitate longitudinal assessments of changing goals and clinical circumstances, major complications or potential need for additional interventions should trigger renewed discussions of patients’ goals (11). For example, GSV standards dictate that “goals of care must be revisited when an older adult experiences an unexpected escalation of care the ICU and must be readdressed at least every three days for all ICU patients” (12). Family meetings also play an important role in tailoring intensive care to patients’ preferences (19). Incorporating palliative care priorities into daily rounding checklists in the Surgical Intensive Care Unit and implementing standardized palliative care documentation may enable researchers to evaluate goal concordance even for complex postoperative trajectories (20,21).

Research focused on patient-centered outcomes following surgical and non-surgical management is essential to provide an evidence base for palliative care in surgery and enable assessment of goal-concordant care (2,22). Specifically, Lilley et al. called for “observational studies measuring patient-reported outcomes… for a broad range of surgical subspecialties, including surgical oncology, neurosurgery, vascular surgery, and trauma” (2). They likewise highlighted the need for “large, multisite studies to compare palliative surgery versus medical management on symptom burden and quality of life” (2). The resulting body of evidence will support not only evidence-based clinical decision making, but also more rigorous research assessments of whether specific interventions were likely to achieve a patients’ desired results compared to available alternatives. Implementation of multidisciplinary conferences generating consensus treatment recommendations for high-risk patients (and documentation thereof) may also inform judgments of goal concordance by grounding assessments of likely outcomes in multidisciplinary expertise (12,23,24).

Conclusions

The systematic review by Kopecky et al. finds that although there have been meaningful additions to the literature since Lilley et al. identified critical gaps in the evidence base for palliative care in surgery, measurement of goal-concordant surgical care remains a horizon for future research. Progress in other palliative care domains such as communication and decision making, integration of palliative care principles into routine surgical practice, and patient-centered outcomes research will support future measurement of goal concordance in seriously ill surgical patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Annals of Palliative Medicine. The article did not undergo external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-1420/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Task Force on Surgical Palliative care; Committee on Ethics. Statement of principles of palliative care. Bull Am Coll Surg 2005;90:34-5.

- Lilley EJ, Cooper Z, Schwarze ML, et al. Palliative Care in Surgery: Defining the Research Priorities. Ann Surg 2018;267:66-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lilley EJ, Khan KT, Johnston FM, et al. Palliative Care Interventions for Surgical Patients: A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg 2016;151:172-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kopecky KE, Florissi IS, Greer JB, et al. Palliative care interventions for surgical patients: a narrative review. Ann Palliat Med 2022;11:3530-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Halpern SD. Goal-Concordant Care - Searching for the Holy Grail. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1603-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanders JJ, Curtis JR, Tulsky JA. Achieving Goal-Concordant Care: A Conceptual Model and Approach to Measuring Serious Illness Communication and Its Impact. J Palliat Med 2018;21:S17-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ernecoff NC, Wessell KL, Bennett AV, et al. Measuring Goal-Concordant Care in Palliative Care Research. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021;62:e305-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Addington-Hall J, McPherson C. After-death interviews with surrogates/bereaved family members: some issues of validity. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;22:784-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sacks GD, Dawes AJ, Ettner SL, et al. Surgeon Perception of Risk and Benefit in the Decision to Operate. Ann Surg 2016;264:896-903. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalbfell E, Kata A, Buffington AS, et al. Frequency of Preoperative Advance Care Planning for Older Adults Undergoing High-risk Surgery: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Surg 2021;156:e211521. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee KC, Walling AM, Senglaub SS, et al. Improving Serious Illness Care for Surgical Patients: Quality Indicators for Surgical Palliative Care. Ann Surg 2022;275:196-202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American College of Surgeons: Geriatric surgery verification program. Available online: https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/geriatric-surgery. Accessed Sep 22, 2022.

- Robbins AJ, Beilman GJ, Ditta T, et al. Mortality After Elective Surgery: The Potential Role for Preoperative Palliative Care. J Surg Res 2021;266:44-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yefimova M, Aslakson RA, Yang L, et al. Palliative Care and End-of-Life Outcomes Following High-risk Surgery. JAMA Surg 2020;155:138-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jacobsen J, Bernacki R, Paladino J. Shifting to Serious Illness Communication. JAMA 2022;327:321-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cooper Z, Koritsanszky LA, Cauley CE, et al. Recommendations for Best Communication Practices to Facilitate Goal-concordant Care for Seriously Ill Older Patients With Emergency Surgical Conditions. Ann Surg 2016;263:1-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kruser JM, Taylor LJ, Campbell TC, et al. "Best Case/Worst Case": Training Surgeons to Use a Novel Communication Tool for High-Risk Acute Surgical Problems. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:711-719.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor LJ, Nabozny MJ, Steffens NM, et al. A Framework to Improve Surgeon Communication in High-Stakes Surgical Decisions: Best Case/Worst Case. JAMA Surg 2017;152:531-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kennedy AC, Jones DA, Eastwood GM, et al. Improving the quality of family meeting documentation in the ICU at the end of life. Palliat Care Soc Pract 2022;16:26323524221128838. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cralley A, Madsen H, Robinson C, et al. Sustainability of Palliative Care Principles in the Surgical Intensive Care Unit Using a Multi-Faceted Integration Model. J Palliat Care 2022;37:562-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilson E, Bernacki R, Lakin JR, et al. Rapid Adoption of a Serious Illness Conversation Electronic Medical Record Template: Lessons Learned and Future Directions. J Palliat Med 2020;23:159-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schwarze ML, Brasel KJ, Mosenthal AC. Beyond 30-day mortality: aligning surgical quality with outcomes that patients value. JAMA Surg 2014;149:631-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koike M, Yoshimura M, Mio Y, et al. The effects of a preoperative multidisciplinary conference on outcomes for high-risk patients with challenging surgical treatment options: a retrospective study. BMC Anesthesiol 2021;21:39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones TS, Jones EL, Barnett CC Jr, et al. A Multidisciplinary High-Risk Surgery Committee May Improve Perioperative Decision Making for Patients and Physicians. J Palliat Med 2021;24:1863-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]