The impact of the Well-Dying Law in Korea: comparing clinical characteristics and ICU admissions

Introduction

A well-dying decision seeks to prevent patients from experiencing a miserable death, which can occur as a result of undesirable life-sustaining treatments. To protect human dignity and values, core legal principles should be implemented to ensure patients’ autonomy. In the United States, the first law on the suspension of life-sustaining treatment was preceded by the case of Karen Ann Quinlan in the New Jersey Supreme Court on March 31, 1976, and California’s Natural Death Act on September 30, 1976. Subsequently, the Patient Self Determination Act (PSDA, 1990) was enacted, highlighting the need to align approaches to end of life care across medical and law. The case has influenced medical professionals and patients’, especially in terms of patient self-determination.

In Korea, a seminal 1997 case, the Case of Boramae Hospital, prompted interest in legislation related to end-of-life care. In this case, medical staff were indicted for murder for suspending life-sustaining treatment for a patient suffering from brain hemorrhage as per the patient’s family’s wishes (1,2). This embarrassed Korea’s medical society and made professionals reluctant to discuss life-sustaining treatment. In 2009, the Kim Grandma Case was recognized as the first case regarding the termination of life-sustaining treatment (3,4). Since then, there have been discussions among medical staff and social actors regarding the best choice for terminally-ill patients and how these decisions should be made in the medical field. These discussions have given rise to recommendations for Korea to legally require patients to complete Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) or Advance Directives (AD) to guarantee their self-determination; this process would replace the Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) form, which has historically been the only such document used in clinical field (5,6). Consequently, the Act on Decisions on Life-sustaining Treatment for Patients in Hospice and Palliative Care or at the End of Life, referred to as the “Well-Dying Law”, was passed in February 2016 in Korea. After a two-year of grace period, the Well-Dying Law was implemented on February 4, 2018.

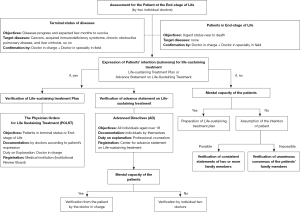

The Well-Dying Law made three key points; First, the “medical status” that would enable the suspension of life-sustaining treatment (itself defined as treatments that expand life in a patient with an uncurable disease) must be defined; for example, patients with worsening health regardless of active medical treatment and those who were expected hardly to recover from their underlying diseases were defined to be in “terminal status”. Second, previously unaccepted documentation (AD and POLST) must be legalized. Third, best practices for handling patients who have not documented their will must be developed; for example, a patent has no documented intent, then at least two doctors should individually judge their medical status and at least two their family members should state what they believed to be the patients’ will regarding life-sustaining treatment before and after they deemed terminal (7) (Figure 1).

By providing guidance, the law might affect patients’ life-long care decisions, especially for those with a critically threatened or chronically ill status likely to receive intensive care before the law’s implementation. Because these legal guidelines gave medical staff the responsibility of actively explaining and gathering specific forms of consent from patients’ legal representatives, it is necessary to find changes in the clinical characteristics of patients who have had intensive care before and after the law’s implementation.

This study sought to compare the clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients admitted to a medical intensive care unit (ICU) in Korea to investigate how medical factors and the criteria for an “appropriate” ICU admission changed before and after the Well-Dying Law. In addition, the change in appropriateness of ICU admission for individual patients was also investigated. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-509/rc).

Methods

Study population

This study was conducted in a medical ICU with 11 beds at the National Medical Center in Korea. Patients admitted to this ICU between November 1, 2017, and June 30, 2018 were eligible for inclusion in the study. We defined the preliminary period as 2 months stretching across March and April 2018 regarding the adaptation of law for the patients who had the lack of opportunities to discuss about the decision of lifelong care based on the Well-Dying Law.

On February 4, 2018, when the Well-Dying Law was enacted, we classified the 83 patients admitted to the ICU from November 1, 2017 to January 31, 2018 as the pre-law adaptation group. The 95 patients admitted from April 1 to June 30, 2018, were classified as the post-law adaptation group. In total, 178 patients were included in the study.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Medical Center (IRB No. H-1806-091-001), and the requirement for written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Study design and data collection

We performed this retrospective study by reviewing the electronic medical records (EMRs) of patients admitted to this ICU for any medical cause. We based this review on medical records at admission (recorded by nurses and physicians), and notes regarding the daily progression of patients. We collected data regarding patients’ cultural and social characteristics by reviewing the medical records compiled by the nurses at admission. Generally, attending nurses on wards interviewed all patients and their family members upon admission. Patients and their family members were asked about the patient’s religion, educational attainment, employment status, and self-reported financial status (i.e., low, middle, or high).

We collected the main cause, and the department of duty at ICU admission. We also gathered information on the use of the ICU; namely: (I) the route for ICU admission (e.g., via the emergency department, general ward, or an ICU at another hospital), and (II) where the patient had received medical care before ICU admission (e.g., home, nursery care, or care in a general ward in another hospital). In addition, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance scale, Acute Physiologic Assessment, and Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) scores, and mental status at ICU admission were also reviewed.

We collected information on the medical cause of illness for ICU admission and clinical outcomes of hospital length of stay (LOS), ICU LOS, and discharge after ICU care in the two groups.

‘Appropriateness’ of ICU admission: priority

There is little evidence on how these guidelines operate in clinical field; accordingly, most decisions seemed to depend on the decisions of medical staff in Korea. In considering what characteristics prioritize a patient for ICU admission in the context of life-sustaining treatment, we consider the patient’s individual details, especially those related to the patient’s ability to receive intensive care. Accordingly, we compared the overall statuses at ICU admission of the patents in our study.

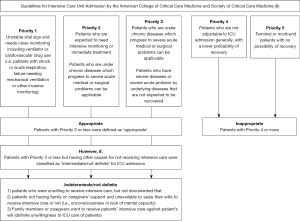

The Guidelines for Intensive Care Unit Admission by the American College of Critical Care Medicine and Society of Critical Care Medicine (8) outline a priority model for ICU admission that classifies patients into five groups based on their health status, including their clinical diagnoses and expected treatments (Figure 2). A retrospective review of patients who had already admitted to the ICU by the two qualified intensivists revealed that patients categorized as Priority 4 or higher were defined as ‘inappropriate’ cases for ICU admission (Figure 2). Patients are categorized as “inappropriate” when they fall into the following four categories: (I) patients admitted for life-sustaining treatment, (II) patients whose quality of life was expected to deteriorate after treatment, (III) patients subject to multiple inappropriate invasive procedures, and (IV) patients whose treatment was unaffordable. Patients categorized as Priority 3 or below, with having other causes for not receiving intensive care were classified as “intermediate/not definite” for ICU admissions if they (I) were unwilling to receive intensive care, but had not documented this, (II) were not supported by family or caregivers’ and unable to state whether they wanted their wills to receive intensive care or not, or (III) did not want to receive intensive care but their family members or caregivers did want them to receive it intensive care. If patients categorized as with Priority 3 or lower did not meet these criteria, then they were defined as “appropriate” for ICU admission.

Statistical analysis

All categorical variables are presented as numbers with percentages, and some non-parametric continuous variables are presented as medians with interquartile ranges. We performed between-group comparisons for non-parametric variables using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables, and a chi-square test for categorical variables. Fleiss’s kappa was used to estimate inter-raters agreements about the inappropriateness of ICU admission before and after the law’s implementation. A two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. We performed all analyses using SAS (version 9.4, Cary, NC, USA). A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

This retrospective study included 178 patients. Within this sample, 83 patients were admitted to the ICU before the enactment of the Well-Dying Law and 95 were admitted after the law’s enactment. The median ages of the pre-law and post-law adaptation groups were 65.0 (IQR 56.0–77.0) and 71.0 (IQR 58.0–77.0) years (P=0.135), respectively. Relatively more men were admitted to the ICU during the study period (78.3% and 71.6%, P=0.388, respectively).

The ECOG on the first day of hospitalization was not significantly different between the two groups (P=0.41). The most common underlying diseases were, in order of frequency: type 2 diabetes (41.0% vs. 45.3%), hypertension (34.9% vs. 33.7%), and heart diseases (31.3% vs. 26.3%). There was no significant difference between the two groups, except in terms of liver disease, which was found to be highly prevalent in the pre-enactment group (27.7% vs. 14.7%, P=0.033) (Table 1).

Table 1

| Characteristics | Before the law (n=83) | After the law (n=95) | P value€ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median, IQR), years | 65.0 (56.0–77.0) | 71.0 (58.0–77.0) | 0.135 |

| Male, n (%) | 65 (78.3) | 68 (71.6) | 0.388 |

| Department in charge of care, n (%) | 0.310 | ||

| Pulmonology | 28 (33.7) | 36 (37.9) | |

| Cardiology | 15 (18.1) | 22 (23.2) | |

| Gastroenterology | 15 (18.1) | 13 (13.7) | |

| Nephrology | 14 (16.9) | 12 (12.6) | |

| Infection | 8 (9.6) | 3 (3.2) | |

| Hemato-oncology | 2 (2.4) | 6 (6.3) | |

| Endocrinology | 1(1.2) | 3(3.2) | |

| ECOG at admission, n (%) | 0.410* | ||

| 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 5 (6.0) | 2 (2.1) | |

| 3 | 25 (30.1) | 32 (33.7) | |

| 4 | 53 (63.9) | 61 (64.2) | |

| Underlying diseases, n (%) | |||

| Type 2 diabetes | 34 (41.0) | 43 (45.3) | 0.564 |

| Hypertension | 29 (34.9) | 32 (33.7) | 0.860 |

| Heart disease | 26 (31.3) | 25 (26.3) | 0.461 |

| Liver disease | 23 (27.7) | 14 (14.7) | 0.033 |

| CVA (stroke, and ICH) | 15 (18.1) | 17 (17.9) | 0.975 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 15 (18.1) | 13 (13.7) | 0.422 |

| Solid organ malignancy | 8 (9.6) | 14 (14.7) | 0.303 |

| COPD | 8 (9.6) | 9 (9.5) | 0.970 |

| Other chronic lung disease | 10 (12.1) | 9 (9.5) | 0.579 |

€, Tested by Chi-square test for categorical variable and by T-test for continuous ones; *, Tested by Fisher’s exact test. Heart diseases includes chronic heart failure and ischemic heart disease; Liver diseases includes liver cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis; Other chronic lung diseases include idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, tuberculous destroyed lung, nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease except COPD. CVA, cerebrovascular attack; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group.

Most patients (81.9% of pre-enactment vs. 77.9% of the post-enactment group) were directly admitted to the ICU directly from their homes; however, a large number of patients were also transferred to the ICU from other non-geriatric hospitals (9.6% vs. 12.6 %) and geriatric hospitals (7.2% vs. 7.4%, respectively). Over 70% of patients were hospitalized via the emergency department (79.5% in pre-enactment vs. 72.6% in the post-enactment group, P=0.530). There was no difference in self-reported economic status (P=0.107) or educational attainment (P=0.167) between the two groups. More than half of the patients in each group were not religious (51.8% for the pre-enactment group vs. 52.6% for the post-enactment group, P=0.672, respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2

| Characteristics | Before the law (n=83) | After the law (n=95) | P value€ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Route of admission, n (%) | |||

| From OPD | 5 (6.0) | 9 (9.5) | 0.530 |

| From emergency department | 66 (79.5) | 69 (72.6) | |

| Direct transfer from other hospitals | 12 (14.5) | 17 (17.9) | |

| Before admission, n (%) | |||

| From home | 68 (81.9) | 74 (77.9) | 0.909* |

| From health care center | 1 (1.2) | 2 (2.1) | |

| From geriatric hospital | 6 (7.2) | 7 (7.4) | |

| From other hospitals | 8 (9.6) | 12 (12.6) | |

| Self-reported economic status, n (%) | |||

| Low | 35 (42.2) | 36 (37.9) | 0.107* |

| Middle | 36 (43.4) | 53 (55.8) | |

| High | 0 | 0 | |

| Not available | 12 (14.5) | 6 (6.3) | |

| Educational attainment, n (%) | |||

| 0–6 years | 14 (16.9) | 23 (24.2) | 0.167 |

| 7–11 years | 21 (25.3) | 16 (16.8) | |

| ≥12 years | 21 (25.3) | 33 (34.7) | |

| Not available | 27 (32.5) | 23 (24.1) | |

| Religion, n (%) | |||

| No | 43 (51.8) | 50 (52.6) | 0.672* |

| Protestant | 13 (15.7) | 12 (12.6) | |

| Catholic | 7 (8.4) | 4 (4.2) | |

| Buddhism | 6 (7.2) | 10 (10.5) | |

| Not available | 14 (16.9) | 19 (20.0) |

The information is collected by patients’ themselves or their caregivers. €, Tested by Chi-square test for categorical variable and by T-test for continuous ones; *, Tested by Fisher’s exact test. OPD, outpatients department.

Medical factors and clinical courses related to ICU admission

There was no difference in the APACHE II score measured at ICU admission (15.5±7.1 vs. 16.6±8.6, P=0.37). The most common purpose of ICU admission as a therapeutic plan for EMR was “close observation” for worsening various diseases (e.g., diabetes, heart disease, liver disease, or gastrointestinal bleeding), followed by respiratory failure. The cause of close observation seemed to decrease after the adaptation of the law, although it was not statistically significant between the two groups (44.5% vs. 39.0%, P=0.54). Pneumonia was the most common cause of illness (entered or written diagnosis on EMR) related to ICU admission, notably, pneumonia, was significantly lower in the pre-enactment group (27.7% vs. 42.1%, P=0.045), followed by an infection other than pneumonia, and heart disease. Liver cirrhosis (LC), the fifth most common cause of diagnosis for ICU admission, was significantly lower in the post-enactment group (12.0% vs. 3.2%, P=0.040) (Table 3).

Table 3

| Clinical parameters | Before the law (n=83) | After the law (n=95) | P value€ |

|---|---|---|---|

| APACHE II score at ICU admission, mean (SD) | 15.5 (7.1) | 16.6 (8.6) | 0.369 |

| Mental status at ICU admission, n (%) | |||

| Coma or semi-coma | 15 (18.1) | 12 (12.6) | 0.356 |

| Drowsy or stupor | 20 (24.1) | 31 (32.6) | |

| Alert | 48 (57.8) | 52 (54.7) | |

| Direct cause of illness for ICU admission, n (%) | |||

| Pneumonia | 23 (27.7) | 40 (42.1) | 0.045 |

| Infection other than pneumonia | 20 (24.1) | 27 (28.4) | 0.514 |

| Heart disease | 15 (18.1) | 27 (28.4) | 0.105 |

| Acute renal failure | 10 (12.1) | 6 (6.3) | 0.182 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 10 (12.1) | 3 (3.2) | 0.040 |

| Malignancy | 5 (6.0) | 2 (2.1) | 0.254 |

| AIDS | 5 (6.0) | 0 (–) | – |

| Stroke | 4 (4.8) | 8 (8.4) | 0.339 |

| COPD | 4 (4.8) | 5 (5.3) | 0.893 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 3 (3.6) | 4 (4.2) | 0.838 |

| Other diseases | 6 (7.2) | 11 (11.6) | 0.325 |

| Main purpose of ICU admission, n (%) | |||

| Rescue of type I RF | 27 (32.5) | 37 (39.0) | 0.373 |

| Rescue of type II RF | 8 (9.6) | 14 (14.7) | 0.303 |

| Sepsis | 19 (22.9) | 24 (25.3) | 0.712 |

| For CRRT application | 6 (7.2) | 4 (4.2) | 0.518 |

| Post-operative care | 2 (2.4) | 3 (3.2) | 0.763 |

| Close observation | 37 (44.5) | 37 (39.0) | 0.542 |

| ICU LOS, days, median (IQR) | 6.0 (4.0–11.0) | 6.0 (3.0–11.0) | 0.493$ |

| Consequence of ICU care, n (%) | |||

| Transfer to general ward | 49 (59.0) | 52 (54.7) | 0.502 |

| Transfer to geriatric hospital | 6 (7.2) | 8 (8.4) | |

| Discharge to home | 0 (–) | 3 (3.1) | |

| Death | 28 (33.7) | 32 (33.6) | |

| Hospital LOS, days, median (IQR) | 16.0 (9.0–24.0) | 24.0 (9.0–46.0) | 0.049$ |

| Consequence of hospital care, n (%) | |||

| Transfer to other hospital | 16 (19.3) | 22 (23.2) | 0.560 |

| Discharge to home | 1 (1.2) | 4 (4.2) | |

| In general ward admission | 34 (41.0) | 30 (31.6) | |

| In-hospital death | 32 (38.5) | 39 (40.0) | |

| Prognosis, n (%) | |||

| ICU mortality | 28 (33.7) | 32 (33.6) | 0.994 |

| In-hospital mortality | 32 (38.6) | 39 (41.1) | 0.734 |

$, Tested by Wilcoxon-Ranksum test for non-parametric variables; €, Tested by Chi-square test for categorical variable and by T-test for continuous ones. Cause of illness, and purpose of ICU admission correspond to multiple items. Heart diseases include Chronic Heart Failure, Ischemic Heart disease. Other diseases include Diabetic Ketoacidosis, Malaria, Alcoholic Ketoacidosis, Vocal Cord Palsy, Exacerbation of Interstitial Lung Disease, Exacerbation of COPD, Asphyxia, Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome, Epilepsy, Hypothermia, Amyloidosis. APACHE, acute physiology and chronic health evaluation; LOS, length of stay; CRRT, continuous renal replacement therapy; RF, respiratory failure; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; SD, standard deviation.

The median duration of total hospitalization was 16.0 days (IQR, 9.0–24.0) in the pre-enactment group and 24.0 days (IQR 9.0–46.0) in the post-enactment group (P=0.049) (Table 3). The LOS in the ICU was not significantly different between the two groups (IQR 4.0–11.0 vs. 3.0–11.0 days, P=0.49, respectively). After ICU care, more than 50% of patients in both groups were transferred to general wards (59.0% vs. 54.7%, P=0.502). Further, about one-third of patients died in the ICU in both groups (33.7% vs. 33.6%, P=0.994). In both groups, most deaths occurred in the ICU (Table 3).

Appropriate ICU admission

The appropriateness of ICU admission evaluated by the two intensivists was supposed to have not changed before and after implementing the law (P=0.646 for Doctor 1, and P=0.315 for Doctor 2, for each). The inter-rater agreement for the appropriateness of ICU admission showed slight or fair agreement both in pre and post-legislation groups [weighted kappa (95% confidence interval); 0.15 (0.08–0.31) for pre-legislation group and 0.14 (0.04–0.25) for the post-legislation group, respectively]. In Doctor 1’s judgement of the appropriateness of ICU admission, the post-legislation group had more inappropriate admissions (24.1% vs. 30.5%); however, the difference was not statistically significant. In terms of inappropriateness, Doctor 1 concluded that the number of patients admitted for terminal care decreased (36.7% vs. 10.3%, P=0.05) after the implementation of the Well-Dying Law. Doctor 2 also concluded that admissions for terminal care had decreased; however, this result was not statistically significant (P=0.102). Both doctors reasoned that most common reason for inappropriate treatment decisions was a lack of communication between caregivers; however, this result was not statistically significant before and after the law’s implementation (Table 4).

Table 4

| Comparison indices | Doctor 1 | Doctor 2 | Inter-rater agreement before/after the law | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the law (n=83) | After the law (n=95) | P value€ | Before the law (n=83) | After the law (n=95) | P value€ | Weighted Kappa$ (95% CI) | |||

| ICU admission appropriateness, n (%) | |||||||||

| Appropriate | 53 (63.9) | 56 (59.0) | 0.646 | 69 (83.1) | 86 (90.5) | 0.315 | 0.15 (0.08–0.31)/ 0.14 (0.04–0.25) |

||

| Intermediate/not definite | 10 (12.0) | 10 (10.5) | 11 (13.3) | 8 (8.4) | |||||

| Inappropriate | 20 (24.1) | 29 (30.5) | 3 (3.6) | 1 (1.1) | |||||

| Reason for inappropriateness at admission, n (%) | |||||||||

| For life-sustaining treatment | 11 (36.7) | 4 (10.3) | 0.050 | 5 (35.7) | 3 (33.3) | 0.102 | N/A | ||

| Expected deterioration of life quality after treatment | 8 (26.7) | 14 (35.9) | 0 | 2 (22.2) | |||||

| Expected unaffordable to costs | 2 (6.7) | 2 (5.1) | 9 (64.3) | 3 (33.3) | |||||

| Expected inappropriate multiple invasive procedures | 9 (30.0) | 19 (48.7) | 0 | 1 (11.1) | |||||

| Reason for inappropriate decision, n (%) | |||||||||

| Demand of patients’ family members | 2 (6.7) | 10 (25.6) | 0.055 | 2 (14.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0.231 | N/A | ||

| Lack of communication between patients and medical staffs | 28 (93.3) | 29 (74.4) | 8 (57.1) | 8 (88.9) | |||||

| Disagreement on medical decision of medical staff around ICU admission | 0 | 0 | 4 (28.6) | 0 | |||||

€, Tested by Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variable; $, Tested by Fleiss’ Kappa statistics between the two intensivists to evaluate inter-rater agreement. ICU, intensive care unit.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate and compare the clinical characteristics and course of patients admitted to a Korea ICU before and after the legislation of the Well-Dying Law. Moreover, we evaluated whether there were any changes in the clinical aspects or appropriateness of ICU admission judged by ICU care doctors before and after the law’s implementation. In this study, the number of patients with LC who were candidates for ICU admission decreased after the Well-Dying law’s implementation. However, we also found that the changes in medical and socioeconomic characteristics among ICU patients and the appropriateness of ICU admission, as defined by the two doctors, were not significant.

Medical factors associated with changes after the law’s implementation

Our study found that ICU admission due to LC aggravation decreased after the law’s implementation. Predicting the mortality of LC patients at the time of referral is complicated. However, various scores have been used to forecast their prognosis (i.e., mortality) to decide the appropriateness of ICU use (9,10). In addition, in the grace period for the law’s implementation, LC was one of several target diseases for end-of-life care in Korea (other target diseases included cancer, AIDS, and COPD). The results of this study are in line with the expectation that the law’s implementation reduced unnecessary ICU admissions. Therefore, prior discussion about life-sustaining treatment according to the Well-Dying Law is required for LC patients, as shown in this study, which suggested a change in the use of ICU pattern.

In this study, the most common cause of illness directly associated with ICU admission was pneumonia, followed by an infection other than pneumonia, and heart disease. Malignancy as a direct cause of ICU admission comprised less than 5% of patients in both groups. There was no significant difference in the clinical and social characteristics between the two groups. A majority of the patients were in the middle or lower class of self-reported economic status both before and after the legislation of the law. Approximately 70% of patients were admitted from their homes via the ER in both groups. As most patients have comorbidities with non-cancerous diseases, we assumed that many patients were hospitalized due to a sudden deterioration related to poorly managed chronic diseases.

Decisions on life-sustaining treatment

In previous studies, lifelong treatment was implemented more frequently for non-cancer patients than in cancer patients (11,12). In our study, the number of cancer patients was relatively small in both groups, which led to statistically insignificant results. Compared to cancer patients who have relatively established prognoses (11,13), the estimation of progression or survival from acute deterioration in chronically ill patients without cancer are more difficult. Medical professionals may have difficulty in deciding their end-of-life care (14,15). Thus, the results of this study suggest that the determination of intensive care for lifelong treatment should be discussed prior to deterioration from underlying diseases, especially for chronically ill patients without cancer.

The Well-Dying Law in clinical practice

There was no difference in the main purpose of ICU admission before and after the law. Before the law, the DNR form had been widely used to express the will of patients or their families’. Of course, the use of DNR form as a standard has influenced the pattern of ICU use (16,17). Compared to the Well-Dying Law, DNR documentation consists of relatively simple components that allow prompt action when patients suddenly deteriorate from chronic diseases, including cancer. Further, documentation is expected for those who are deteriorating due to underlying diseases and who require intensive life-sustaining care even though this document does not have any legal power (6,18). Notably, when the Well-Dying Law was implemented, some clinicians worried about the labor-induced and impractical legal requirements medical staffs would face, especially in terms of defining the terminal status of patients and documenting their wills or the wills of their legal relatives.

Our study examined whether there were changes since the establishment of the Well-Dying Law. However, even within a short-term period after the change, there was no difference in ICU mortality or appropriateness of ICU admission. In this study, two intensivists appraised the appropriateness of ICU admission and found that it did not change before and after implementing the law. This might be partially due to a lack of education on documents that were newly adopted with the Well-Dying Law, which mandates a complex documentation and registration process, and an unfamiliarity with the law’s guidelines for terminal diagnoses (compared to DNR). Notably, documentation mandated by the Well-Dying Law requires thorough discussion about end-of-life care before the dying process. In our study, the results of surveillance involving the healthcare provider’s department internal medicine showed that about half of the sample had not received education about the Well-Dying Law, even six months after its implementation (unpublished data). Further studies should be done on clinical characteristics and appropriateness of ICU admissions after physicians have received proper education and gained sufficient experience with the law.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate ICU use after the implementation of the Well-Dying Law in Korea. We found that the appropriateness for ICU admission was not altered by the legislation for two physicians. If the law is applied in the clinical field with clear processes, may have many benefits, such as reducing legal conflicts between medical staff and patients’ families, and the medical cost of health care. Moreover, the law could also stand to improve the social and medical environment of hospice care for patients with non-cancer chronic diseases.

Limitations

Despite these meaningful findings, this study has several limitations. First, this study was based on a single medical unit in a single center. Second, the judgement of definite end-stage or terminal status for patients with chronic diseases remains difficult even though Korean guidelines for determining terminal status for patients with chronic diseases (19) were published after the law had passed. However, we performed an overall assessment for patients and asked two intensivists to evaluate the benefits and risks of ICU admissions using updated guidelines (8). Third, relatively few cancer patients were included, and the stage of individual patients was unavailable. The results of this study are hardly applicable to cancer patients. However, as previously mentioned, terminal care decisions for chronic disease patients tend to be more difficult because it can be harder to predict their clinical courses than those of cancer patients. Fourth, due to this retrospective design, the circumstances of the ICU at the time of each patient’s referral, such as the availability of ICU beds or space for accommodating those with other infectious diseases, could not be assessed. Although it was a standard process in our hospital for ICU admission, it might have influenced the biased use of ICU. Fifth, ICU attendings could not be blinded for the implementation of the law at the time of ICU admissions, this might have influenced their decision on ICU admission (rather than by medical status). Finally, further studies on long-term changes including the clinical prognosis of ICU patients and comprehensive transition of intensive care decisions, are necessary.

Conclusions

Most clinical characteristics, ICU prognoses, and the appropriateness of ICU admission did not change after the implementation of the Well-Dying Law in Korea. However, fewer patients with LC received ICU care less after the law’s implementation. As expected, the law has become established, and discussions about life-sustaining treatments for chronically ill terminal patients, especially regarding intensive care, have become more important. Further studies should be conducted on the social and legal benefits of the law’s influence on medical decisions.

Acknowledgments

The language in this document has been checked by at least two professional editors, both native speakers of English (http://www.editage.co.kr).

Funding: This research was supported by a grant from National Medical Center, Republic of Korea (No. NMC2018-MS-02). The funding source was not involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, or data interpretation of this study.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-509/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-509/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-509/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-22-509/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Medical Center (IRB No. H-1806-091-001). The requirement for written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Seoul High Court Decision, Republic of Korea, 98No1310 (2002).

- Well-dying controversy is raised by Boramae hospital incident. Asia Business Daily. 2015 Dec 9. Available online: http://www.asiae.co.kr/news/view.htm?idxno=2015120909090909325

- Supreme Court Decision, Republic of Korea, 2009Da17417 (2009).

- Park H. The implications and significance of the Case at Severance Hospital. J Korean Med Assoc 2009;52:848-55. [Crossref]

- Mullick A, Martin J, Sallnow L. An introduction to advance care planning in practice. BMJ 2013;347:f6064. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim DK. Hospice-Palliative Care and Law. The Korean Journal of Medicine 2017;92:489-93. [Crossref]

- National Agency for Management of Life-Sustaining Treatment. The Korea National Institute for Bioethics Policy, Seoul. Available online: https://www.lst.go.kr/main/main.do.

- Nates JL, Nunnally M, Kleinpell R, et al. ICU Admission, Discharge, and Triage Guidelines: A Framework to Enhance Clinical Operations, Development of Institutional Policies, and Further Research. Crit Care Med 2016;44:1553-602. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peng Y, Qi X, Guo X. Child-Pugh Versus MELD Score for the Assessment of Prognosis in Liver Cirrhosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2877. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramzan M, Iqbal A, Murtaza HG, et al. Comparison of CLIF-C ACLF Score and MELD Score in Predicting ICU Mortality in Patients with Acute-On-Chronic Liver Failure. Cureus 2020;12:e7087. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lau KS, Tse DM, Tsan Chen TW, et al. Comparing noncancer and cancer deaths in Hong Kong: a retrospective review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;40:704-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoon SE, Nam EM, Lee SN. End-of-Life Care Practice in Dying Patients with Do-Not-Resuscitate Order: A Single Center Experience. The Korean Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care 2018;21:51-7. [Crossref]

- Kim JM, Baek SK, Kim S-Y, et al. Comparison of End-of-Life Care Intensity between Cancer and Non-cancer Patients: a Single Center Experience. The Korean Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care 2015;18:322-8. [Crossref]

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, et al. Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 2005;330:1007-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Glare P. Predicting and communicating prognosis in palliative care. BMJ 2011;343:d5171. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eliasson AH, Howard RS, Torrington KG, et al. Do-not-resuscitate decisions in the medical ICU: comparing physician and nurse opinions. Chest 1997;111:1106-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fuchs L, Anstey M, Feng M, et al. Quantifying the Mortality Impact of Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2017;45:1019-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JE, Goo AJ, Cho BL. The Current Status of End-of-Life Care in Korea and Legislation of Well-Dying Act. Journal of the Korean Geriatrics Society 2016;20:65-70. [Crossref]

- Lee SM, Kim SJ, Choi Y, et al. Consensus guidelines for the definition of the end stage of disease and last days of life and criteria for medical judgment. J Korean Med Assoc 2016;61:509-21. [Crossref]