Lessons learned from New York’s community approach to advance care planning and MOLST

Introduction

We all face death. Too often, death is viewed as a medical failure rather than the final chapter of life. Caring for the dying is the ultimate in professionalism. Yet, humane care for those approaching death is a social obligation not adequately met in the communities we serve.

Advance care planning (ACP) is a process of planning for future medical care in the event an individual is unable to make their own medical decisions. ACP assists an individual in preparing for a sudden unexpected illness or injury, from which an individual may recover, as well as the dying process and ultimately death.

Initiating ACP early is relevant at all ages; no age group is immune from acute illness or injury, complex chronic conditions or death. Improving communication and ACP is critically important for all ages facing the end of life, including adults, adolescents and children.

In 2014, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released “Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life”, a comprehensive review of end-of-life care in the U.S(1). The IOM report concludes the U.S. health care system is poorly designed to meet the needs of patients near the end of life and major quality gaps exist. As a result, patients and families are suffering. Major changes to the health care system are needed to meet patients’ end-of-life care needs and informed preferences in a high-quality, affordable, and sustainable manner. Patient-centered, family-oriented approach to care near the end of life should be a high national priority. “Significant opportunities exist to improve and align financial and programmatic incentives across health and social services programs, develop incentives to implement program models that have demonstrated how to achieve better care at lower cost, to better target complex care interventions and tailor resources to individual needs, and to use social services to ease the burden on families and enhance quality of life” (1). To take advantage of these opportunities and accomplish change recommended in the five key recommendations, urgent attention and action is needed from numerous stakeholder groups. Compassionate, affordable, and effective care is an achievable national goal, but improved oversight is needed to ensure quality care, control costs, increase transparency, and ensure accountability (1).

Prior to release of this latest IOM report, the IOM played a key role in raising awareness of the needs surrounding end-of-life care. In 1997, the IOM produced the report “Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life” that focused on adults (2). In 2003, the IOM report “When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families” recognized the needs of children and their families facing end of life (3). These reports had a major impact on end-of-life care and new models, programs, policies, providers, and systems of care developed as a result. Building on these models is an important step in moving forward with current recommendations (1).

The Greater Rochester New York area responded to the IOM’s call to action in 1997 and developed a community approach to ACP that was expanded across New York State (NYS).

The model that has been taken statewide includes implementation of two complementary ACP programs, each unique and specific to the appropriate population:

- Community Conversations on Compassionate Care (CCCC): advance directives for all individuals 18 years of age and older; or emancipated minors;

- Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST): MOLST for seriously ill persons of all ages facing the end of life. MOLST is New York’s nationally-endorsed Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) Paradigm program.

The model has been built and expanded throughout NYS. The CCCC program was developed to support the MOLST program at a time when no one, not even a concerned family member, had the right to make decisions about medical treatment for patients who lacked capacity, except Do Not Resuscitate (DNR), unless the patient had signed a health care proxy or left “clear and convincing evidence” of his or her treatment wishes.

The basic principles relating to targeted interventions based on the behavioral readiness for the ACP process, effective communication, shared medical decision-making that is well informed, and the ethical framework for making decisions to withhold and/or withdraw life-sustaining treatment can be applied in all states and countries. The model aligns with the model proposed by the IOM committee of when to discuss end-of-life issues at appropriate decision points throughout life. The model proposes who should be included in such conversations and what topics should be covered, including patient preferences (1).

Materials and methods

Background

In response to the 1997 IOM report, the Rochester Independent Practice Association (RIPA) in conjunction with BlueCross BlueShield of the Rochester Area (BCBSRA) each identified “End-of-Life Care/Palliative Care” as a key focus for quality improvement efforts in 1999. A joint RIPA/Blue Cross End of Life/Palliative Care Professional Advisory Committee (Committee) was formed to collaborate and identify means of improving the quality of care at the end-of-life. A community-wide survey was identified as the first step (4). The survey was designed and distributed to local hospitals, home care agencies, hospices, disease management programs and nursing homes. Based on a response rate of 50%, the Rochester (New York) Community End-of-life Report revealed that only 38% of hospital patients, 40% of clients in one home care agency, and 72% of residents in our communities’ skilled nursing facilities had advance directives in place (4). Additionally, home care agencies reported that advance directives were in place for only 23% of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)/emphysema, 9% of cancer patients, 8% of patients with heart failure, and 6% of dementia patients (4). Thus, prior to the initiation of the community approach to ACP, statistics for the communities in upstate New York mirrored national statistics on end-of-life care (5).

In a 2001 survey of seniors conducted by BCBSRA, 40% of seniors indicated that their physicians had not addressed the issue of ACP, while at the same time, 75% of deaths in Monroe County in 1998 were individuals aged 65 years or older.

Given the survey results regarding ACP, the Committee concluded the community needed to focus on “assuring that a greater percentage of patients, especially patients with chronic debilitating illnesses, understand, complete, and use advance directives. Once completed, health care institutions must ensure their availability and commit to honoring them” (4).

Data from the Community-Wide End-of-Life Survey Report was presented and reviewed by the Rochester Health Commission and the Rochester Health Care Forum Leadership. As a result, the Community-wide End-of-life/Palliative Care Initiative (Initiative) was added to the community forum and launched in May 2001. The Initiative is a healthcare and community collaborative that focuses on implementation of a broad set of end-of-life/palliative care projects that result in quality improvements in the lives of those facing death. Support for the Initiative has been generously provided by Excellus BlueCross BlueShield (BCBS) since 2001. The original advisory group set direction, provided oversight, and initiated a set of broad end-of-life/palliative care projects. Two workgroups were established to improve ACP. Long term goals were shared with the Rochester community (6):

- Every adult (at least 18 years of age) in Greater Rochester Area will identify in writing the person they choose to speak for them and make decisions about medical conditions when they are unable to speak for themselves in the future (Health Care Proxy);

- Every adult will have meaningful discussions with their proxy, family and personal physicians about their wishes as they pertain to end-of-life/palliative care;

- Every adult will have access to an easily recognizable document so that every individual can identify this person. This document will express how a person wishes to be treated if he/she is seriously ill and unable to speak for himself/herself. It will address medical, personal, emotional and spiritual needs;

- Every adult will have access to educational sessions about planning for future health care decisions as well as meaningful discussions about approaches to care at the end-of-life. These will occur routinely in senior living communities, houses of worship, community organizations, doctor’s offices, hospitals and nursing homes;

- Every individual with a life threatening illness or chronic disease will have completed an advance directive describing their wishes, goals of care, values and beliefs;

- Every individual will have their wishes, goals of care, values and beliefs reviewed and updated periodically;

- Every individual who is approaching death will have wishes and goals of care honored regardless of the setting in which care is delivered;

- A uniform community-wide MOLST form will be recognized, accepted in all settings, and accompany the patient as they move from one site of care to another;

- Electronic storage of prepared advance directives, organ donation information, and medical orders for all patients will be available and accessible to providers.

The long term goals guide the development and implementation of the community approach to ACP and complementary two programs:

- CCCC;

- MOLST.

Community Conversations on Compassionate Care (CCCC)

CCCC is an ACP program designed to motivate all adults 18 years of age and older, as well as emancipated minors, to start ACP discussions that clarify personal values and beliefs; choose the right health care agent who will act as their spokesperson; and complete a health care proxy. CCCC combines storytelling and “Five Easy Steps” that focus on the individual’s behavioral readiness to complete a health care proxy (7). CCCC encourages completion of a health care proxy when healthy, as well as review and update the advance directive routinely along the health-illness continuum (Figure 1) from wellness until end of life (8).

Human behavior is too complex to systematically and consistently respond to one type of intervention (9-11). Individuals who are successful in adopting change follow an unwavering sequence of activities and attitudes prior to finally changing an undesirable lifestyle. Wellness interventions apply the transtheoretical model of change theory. Similarly, a framework for behavior change can be applied to encouraging ACP.

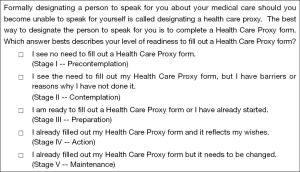

In 2002, staging questions to assess health care proxy readiness were developed to assess the success of CCCC educational workshops on ACP (12). Beginning in stage 1 (precontemplation), the person sees no need to complete an advance directive and thus, the primary intervention focuses on providing educational information about advance directives. Moving into stage 2 (contemplation), the person sees the need to complete an advance directive but has reasons why the advance directive is not done; consequently, interventions seek to identify and remove patient barriers, such as:

- I do not know enough about it; I do not know what it is;

- It is not important;

- I do not want to think about it; I do not want to discuss it;

- I do not have enough time;

- I do not know how to bring up the subject with my family;

- It is too difficult.

In progressing to stage 3 (preparation), the person is ready to complete an advance directive or has already started one, the interventions focus on motivating the patient. Storytelling has been found to be effective in this stage in the workshop setting and prompted the development of CCCC videos that illustrate different real stories in order to expand the reach. Finally in stage 4 (action), the person has completed an advance directive that reflects personal values and wishes. Along with completion of the document, it is important to discuss patient values and preferences, encourage family discussion, assess the appropriateness of the designated medical decision-maker and share copies of the advance directive. Stage 5 (maintenance) reflects the need to review and update advance directives.

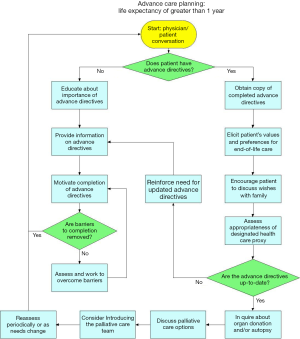

Targeted interventions that encourage ACP discussions can be focused and linked with the stages of change to the patient’s current condition and behavioral readiness to complete an advance directive, as exemplified in Figure 2 (8).

Counseling should include key elements of the ACP process as outlined on the clinical pathway in Figure 3 (8).

The CCCC toolkit focuses on “Conversations Change Lives” and includes:

- ACP Booklet (English, Spanish);

- ACP Brochure, Poster and Table Topper;

- ACP Facilitator Training;

- ACP Clinical Pathways;

- Behavioral Readiness “tools”;

- CCCC workshop;

- CCCC standardized presentation;

- CCCC videos;

- ACP Public Service Announcements videos;

- CCCC video on-line with Five Easy Steps;

- Compassion And Support YouTube Channel;

- On-line resources at CompassionAndSupport.org.

Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST)

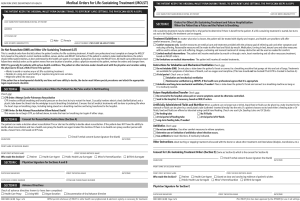

MOLST is a clinical process that results in completion of the MOLST form, a set of medical orders that reflect the individual’s preference for life-sustaining treatment they wish to receive and/or avoid (Figure 4).

MOLST is approved for use and must be followed by all providers in all clinical multiple settings, including the community. MOLST is the only medical order form approved under New York State Public Health Law (NYSPHL) that emergency medical services (EMS) can follow both DNR/Allow Natural Death and Do Not Intubate (DNI) orders in the community in New York. MOLST is New York’s nationally-endorsed POLST Paradigm program.

MOLST emphasizes discussion of personal values and beliefs, the goals for the individual’s care and shared medical decision-making between health care professionals and the medical decision-maker. Clinicians are guided in the process by use of the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) and Office for Persons with Developmental Disabilities (OPWDD) MOLST Checklists. These Checklists and the associated MOLST Chart Documentation Forms integrate a standardized “8-Step MOLST Protocol” (Figure 5) to guide a thoughtful discussion and process, as well as incorporate the ethical framework and legal requirements for making decisions to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment in NYS (13-15).

The ethical framework and legal requirements to withhold/withdraw life-sustaining treatment in NYS must be followed whether or not the MOLST form is used (13-17).

MOLST began with creation of the original MOLST form as a project of the Initiative in fall 2001. The original MOLST form was completed in November 2003. MOLST was adapted from Oregon’s POLST and integrates NYSPHL. Implementation began on a voluntary basis in Rochester health care facilities shortly thereafter. A broader regional launch in January 2004 resulted in expansion to surrounding counties.

As regional adoption ensued, simultaneous collaboration with the NYSDOH began in March 2004. As a result, a revised form consistent with NYS law was approved by the NYSDOH for use as an institutional DNR in all health care facilities throughout NYS in October 2005. NYSDOH sent a letter on January 17, 2006, confirming its approval (18). This approval did not require legislative action, but achieved significant growth in the MOLST program across the state. Implementation of the MOLST program began in health care facilities, including hospitals and nursing homes, and spread to assisted living facilities, enriched housing, and the community.

Legislation was required to permit use of MOLST as an alternative form in the community. With passage of the MOLST pilot project legislation and the chapter amendment [2006], NYSDOH approved the MOLST for use in the community as a non-hospital DNR and DNI in Monroe & Onondaga counties. The Monroe & Onondaga counties MOLST Community Implementation Team (Team) was formed in 2006 to oversee a 3-year pilot project. In addition to collaboration with the NYSDOH, the Team partnered with the Medical Society of the State of New York (MSSNY), New York State Bar Association (NYSBA), the Healthcare Association of New York State (HCANYS), New York State Health Facilities Association (NYSHFA), the New York Association of Homes and Services for the Aging (NYAHSA), the Hospice and Palliative Care Association of New York State (HCPCANYS), New York State Office for the Aging (NYSOFA), New York State Society on Aging (NYSSA), the Greater New York Hospital Association (GNYHA), and other professional associations, health care facilities, systems and agencies across NYS.

A successful MOLST pilot project resulted in Governor David Paterson signing a law in 2008 that made MOLST permanent and statewide, thereby changing the scope of practice for EMS across NYS (19). MOLST was consistent with NYSPHL section 2,977 [13], authorizing the use of MOLST, at the time the Public Health Law was amended. Since then, it has been repealed and a new NYSPHL, Article 29-CCC, was created to govern non-hospital DNR orders (19). The new article is now consistent with the new Family Health Care Decisions Act (FHCDA) law and cannot be altered. MOLST has been reviewed annually since 2005, complies with NYSPHL, and has been adapted to meet clinical needs.

The NYSDOH updated the MOLST form (DOH-5003) in June of 2010 to make it more user-friendly and to conform to the procedures and decisionmaking standards set forth in the FHCDA (20). The MOLST Statewide Implementation Team was launched in May 2010 to oversee effective statewide implementation of the MOLST program and to support NYSDOH implementation of the FHCDA and revision of the MOLST form (20). The statewide team replaced the bi-county team that was in place from 2005-2010.

Electronic MOLST (eMOLST) and New York’s eMOLST registry

eMOLST is an electronic form completion and process documentation system for the NYSDOH-5003 MOLST form that also serves as New York’s eMOLST registry. The web-based application, found at NYSeMOLSTregistry.com, includes programming to eliminate errors, guides conversations between clinicians and the medical decision-maker and family, the ethical framework & legal requirements for making decisions regarding cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and life-sustaining treatment, and documentation of the discussion. eMOLST may be used with paper records, integrated in an Electronic Medical Record (EMR) or hybrid system, allows for electronic signature for providers and for the form to be printed for needed workflow in the paper world. eMOLST helps to ensure quality, improve patient safety, reduces patient harm and achieve the triple aim.

Results

The CCCC program

CCCC has generated positive outcomes with respect to advance directive completion, particularly for health care proxies, and has been an influence on larger culture change in upstate New York with respect to ACP. Data on the success of CCCC is captured through surveys from CCCC workshop attendees, a community-wide survey of upstate New Yorkers, and health care proxy completion among employees at Excellus BCBS, an organization that has driven CCCC interventions among their employees and the community for over 10 years (21-23).

Prior to the launch of the CCCC program, advance directive completion was measured in the Rochester area through chart audits/surveys of key hospitals, nursing homes, hospice programs, and home health agencies. As you would expect, because these are healthcare institutions the portion of patients/residents with advance directives in place is significantly over-represented, however, it was the best estimate of the community at the time. Of the facilities surveyed, hospitals are the most general site of care and indicated that 38% of patients had advance directives in their records (4). Advance directives included health care proxies, living wills and DNR orders for the purposes of the survey. This indicated that the Rochester area had a lot of work to do regarding ACP. National surveys at the time indicated that approximately 20% of people had an advance directive in the general population; it seemed that Rochester was performing similar to the nation (5).

With the launch of CCCC pilot in the Rochester area, tracking results was important to make the case for growing the program across upstate New York. The pilot data were collected for 2 years [2002-2004] and analysis indicated that the workshop format motivated individuals to complete an advance directive (21). Among those who attended a CCCC workshop, 48% had a health care proxy at the start of the workshop; 6-8 weeks later, 55% had an advance directive. The improvement in advance directive completion is statistically significant (P=0.01) (21).

The CCCC program was shared across upstate New York over several years. In order to attempt to measure community-wide culture change surrounding ACP practices, in 2008, Excellus BCBS commissioned the survey of 2,000 individuals in 39 upstate New York counties regarding their knowledge, attitudes and actions towards ACP and advance directive completion. This survey is the most comprehensive study ever done in upstate New York to assess completion of health care proxies and living wills. Evidence suggests that ACP completion is driven, in part, by community education and physician communications with patients. The highest rate of discussion with doctors occurred in the Rochester area (47%), where the CCCC program was first launched, compared with the Utica area (27%); similarly, health care proxy completion was highest in Rochester (47%) and lowest in Utica (35%). Survey responses from locations where doctors were more likely to have discussed ACP with their patients had higher completion rates of advance directives (22).

The 2008 survey results can be compared with the best-available national data. In an analysis of 7,964 adults 18 and older who completed the health styles survey in the years 2009 and 2010. The health styles survey is a mail panel survey that is designed to be representative of the U.S. population. Among survey respondents, only 26.3% had completed an advance directive (24). In this study there was no differentiation between health care proxies, also known as durable power of attorney for healthcare, and living wills. The major concern with that is if many of the respondents only had living wills and not health care proxies there are challenges in place when no decision-maker is chosen in the event that the patient loses the ability to speak for himself. Other researchers and clinicians have noted that living wills may have limited value, particularly if no health care proxy is completed, because they often capture information that is too general or too specific, as people cannot foresee all their future healthcare needs or situations (25-28).

Throughout this time, the CCCC workshops and accompanying ACP resources were also made available to employees at Excellus BCBS. Excellus BCBS employees (a population of approximately 6,000 individuals) have been surveyed for over 10 years with regards to ACP completion, with a special focus on health care proxies. The first ACP survey was done in 2002, and the most recent done in 2014. Between 2002 and 2008, health care proxy completion increased from 30% [2002], to 34% [2006] to 43% [2008] (22). In 2009 there was a major push among employees to complete health care proxies and have ACP conversations with families; that year health care proxy completion rates increased to 53%. Since then they have continued to climb and have consistently been at 58% for survey years 2012, 2013 and 2014 (23).

As a result of the CCCC program’s positive outcomes it has been nationally recognized as an example of a preferred practice from the National Quality Form for “develop(ing) and promot(ing) healthcare and community collaborations to promote ACP and completion of advance directives for all individuals” (29).

MOLST & eMOLST

The MOLST program has passed through several critical developmental phases described in the background section of this article. Through each of these steps, visible growth in the MOLST program across NYS occurred.

During the MOLST pilot phase, acute and long-term care facility engagement in the MOLST program was measured in Monroe and Onondaga counties, the two pilot counties where MOLST forms could be honored by EMS without an accompanying NYSDOH non-hospital DNR. A survey done in 2006 attempted to “understand early penetration of the MOLST community initiative across healthcare settings and identify facility types associated with highest efficiency in program implementation” (30). Surveys were distributed to 115 facilities and 112 were received back (a 97.4% response rate). Forty-six percent of facilities had already implemented the MOLST at the time of the survey (approximately 4 to 6 months into the 2-year pilot period). Hospitals and nursing homes were significantly more likely to have already implemented the MOLST tool, followed by hospices and Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) programs. Overall, 76% of facilities were planning to implement the MOLST at that time (30).

By the end of the pilot period in early 2008, MOLST was being used as a “facility form” (but not authorized for use in the community) in facilities in all 62 counties in NYS (31).

On July 8, 2008 the MOLST form became legal for use in the community and all care settings in all NYS counties. Honoring MOLST in all New York counties required a change in scope of practice for EMS. At that time there was a dramatic increase in the number of requests for printed MOLST forms from across NYS. In this period all MOLST forms in New York were printed and shipped for free by Excellus BCBS in Rochester; the form was not posted online for downloads. Data from MOLST form orders indicates that from January through June of 2008 (prior to passage of the MOLST legislation) there were 181 orders for 21,667 MOLST forms. From July through December of the same year there were 593 orders for 70,996 MOLST forms; after the passage of legislation there was a dramatic increase of nearly 50,000 more forms than would have otherwise been expected in a 6-month timeframe (23).

In 2010 after the passage of Family Health Care Decisions Act the MOLST form became a NYSDOH form. PDFs were posted online on the NYSDOH website and on CompassionAndSupport.org. Excellus BCBS continued printing MOLST forms and shipping them to facilities and individuals around NYS as they were requested. Again, requests for MOLST forms dramatically increased after the enactment of FHCDA and launch of the new NYSDOH MOLST form on June 1, 2010. Between January and the end of May of 2010 there were 384 orders totaling 55,537 MOLST forms. Between June and December of 2010 there were 769 orders totaling 172,034 MOLST forms; approximately three times as many forms were shipped as would normally be expected in that timeframe, indicating another surge in MOLST use (23).

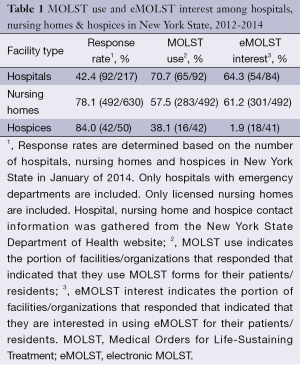

From 2012-2014 all hospitals, nursing homes and hospices in NYS were surveyed about their use of MOLST and interest in eMOLST. Surveyors were trained to call each facility in random order and re-call non-respondent facilities to try to capture the best data available. Surveyors spoke with the director of nursing or the director of social work at each organization to help guarantee the accuracy of the data collected. Results of the survey are displayed in Table 1.

Full table

These data reflect positively on the growth of the MOLST program across NYS and the future for eMOLST as an electronic form completion and documentation tool and registry for New York’s MOLST forms over the next several years.

Discussion

Consistent leadership of New York’s two complimentary ACP programs since inception supports the need for several elements to ensure effectiveness of a community approach:

- Initiating ACP early;

- Culture change;

- Provider training;

- Community education & empowerment;

- Thoughtful discussions;

- Shared, informed decision-making;

- Care planning that supports MOLST;

- System implementation led by system and physician champions;

- Sustainable payment stream based on improved compliance with person-centered goals, preferences for care and treatment. Incentives should be tied to improved patient and family satisfaction and reduced unwanted hospitalizations.

Thoughtful MOLST discussions that focus on person-centered, family-oriented goals for care take time. Depending on the readiness for ACP, it may take more than one session to complete the MOLST process before completing the MOLST form. Health care professionals must ensure the shared medical decision making process is well informed and consistent with the ethical framework to make medical decisions to withhold and/or withdraw life-sustaining treatment. In New York, the ethical framework aligns with legal requirements under NYSPHL. In order to be effective, MOLST orders must be supported by a person-centered, family-oriented care plan and family and caregivers must be educated about what to do in an emergency. The MOLST process involves both face-to-face and non-face-to-face time.

The patient’s goals for care may change over time prompting a change in treatment preferences and a need to change the MOLST form. In discussions with providers, a major barrier identified is inadequate reimbursement for time spent. Excellus BCBS developed an improved reimbursement model for trained providers (physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants). This reimbursement model is consistent with IOM recommendations (1).

Improving end-of-life care has been a major initiative for Excellus BCBS since 2001. Excellus BCBS empowers individuals to receive quality care that honors their preferences, while ensuring that families are supported. It prioritizes educating providers to perceive the deaths of patients not as a failing, but as an opportunity to ensure that end-of-life wishes are respected. Excellus BCBS has developed coalitions across the state and participates in national discussions in order to share successes, learn from others, and expand the reach of these initiatives. The efforts of Excellus BCBS serve to fulfill its mission to “reach out to all segments of the communities we serve, particularly the poor and the aged and others who are underserved, to enhance quality of life.”

In 2011 Excellus BCBS aimed to determine the impacts of its initiatives. The impacts that the initiatives have had on cultural change surrounding end-of-life conversations can be documented in many ways. The value of this work is summarized well, although not completely, in the following points. In the past 10 years Excellus BCBS has:

- Started and lead a continually evolving statewide discussion on palliative and end-of-life care;

- Developed and implemented five major community projects that are utilized statewide and recognized as best practices nationally;

- Received 15 national awards for these programs;

- Succeeded in passing 4 major changes to NYSPHL;

- Gained remarkable earned positive media coverage for this work.

Effective ACP models promote culture change through professional training, community education, system implementation and continuous performance improvement focused on quality. Community engagement is necessary to promote awareness and readiness for ACP discussions through education and empowerment. Health care and community collaborative partnerships can be formed by engaging individuals and faith-based, patient advocacy, community and professional organizations to help achieve the goal.

The growth of this approach to ACP, end-of-life care and palliative care has been successful across New York with broad implementation of MOLST, and more recently eMOLST, in particular. Other states can adopt and modify this model, including the eMOLST application, specific to their own legislation, regulation and priorities. New York’s evidence-based model is a process-driven approach to ACP and end-of-life care that is relevant in all care setting for all populations and is applicable in all states across the country. Although laws and documents vary state by state, the conversation and process remains the same, allowing for replication and customization of this model nationwide.

By encouraging conversations that focus on planning for our death and dying, we can begin to truly experience and appreciate life. As we face the words openly, we recognize and accept our own vulnerability. Moreover, we can begin to truly live each day to the fullest, appreciate our relationships with each other, share our differences (whether cultural, spiritual, professional or otherwise) and recognize our similarities. In today’s world, health care innovation is most often defined by what can be achieved through the science of medicine and technology. There is much that can be achieved through the art of compassion, collaboration and communication.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2014/Dying-In-America-Improving-Quality-and-Honoring-Individual-Preferences-Near-the-End-of-Life.aspx

- Field MJ, Cassel CK. eds. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press, 1997.

- Field MJ, Behrman RE. eds. When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2003.

- RIPA/Blue Cross End-Of-Life/Palliative Care Professional Advisory Committee. Rochester Community End-Of-Life Survey Report: October–November 2000. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: http://www.compassionandsupport.org/pdfs/about/Rochester%20Community%20End%20of%20life%20Report%20012901.pdf

- Last Acts. Means to a better end: a report on dying in America today. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/handle/1805/722

- Bomba PA. Rochester Health Care Forum Report to the Rochester Community. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: https://www.compassionandsupport.org/pdfs/about/Report%20to%20the%20Rochester%20Community.112901.pdf

- Community Conversations on Compassionate Care (CCCC) Video: Five Easy Steps. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: https://www.compassionandsupport.org/index.php/for_patients_families/advance_care_planning/five_easy_steps

- Bomba PA, Vermilyea D. Integrating POLST into palliative care guidelines: a paradigm shift in advance care planning in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2006;4:819-29. [PubMed]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. eds. The transtheoretical approach: crossing traditional boundaries of therapy. Homewood (IL): Dow Jones-Irwin, 1984.

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Common process of self-change in smoking, weight control and psychological distress. In: Shiffman S, Wills TA. eds. Coping and substance use: A Conceptual Framework. New York: Academic Press, 1985:345-63.

- Prochaska JO, Goldstein MG. Process of smoking cessation. Implications for clinicians. Clin Chest Med 1991;12:727-35. [PubMed]

- Bomba PA, Doniger A, Vermilyea D. Staging Questions: Health Care Proxy Readiness. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: http://www.compassionandsupport.org/pdfs/professionals/training/HCP_Readiness_Form_Updated_021810.pbomba_.pdf

- MOLST Chart Documentation Forms (align with NYSDOH Checklists). [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: http://www.compassionandsupport.org/index.php/for_professionals/molst/checklists_for_adult_patients

- MOLST Chart Documentation Form: Aligns with Legal Requirements Checklist for Minor Patients. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: http://www.compassionandsupport.org/pdfs/professionals/molst/MOLST_Chart_Documentation_Minor_Checklist.120110_.pdf

- MOLST Legal Requirements Checklist for Individuals with Developmental Disabilities. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: http://goo.gl/RP6eO

- Bomba PA. Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST): 8-Step MOLST Protocol. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: http://www.compassionandsupport.org/pdfs/homepage/MOLST_8_Step_Protocol._revised_032911_.pdf

- Health Care Proxy: Appointing Your Health Care Agent in New York State. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: http://www.health.ny.gov/forms/doh-1430.pdf

- Conroy MJ, Wronski E, Servis K. State of New York Department of Health. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: http://www.compassionandsupport.org/pdfs/legislation/MOLSTDOHapprovalletter.pdf

- Bomba PA. Landmark legislation in New York affirms benefits of a two-step approach to advance care planning including MOLST: a model of shared, informed medical decision-making and honoring patient preferences for care at the end of life. Widener Law Review 2011;17:475-500.

- New York State Department of Health. Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST). [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: http://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/patients/patient_rights/molst/

- Community Conversations on Compassionate Care Workshop Attendee Responses. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: http://www.compassionandsupport.org/pdfs/research/Community_Conversations_on_Compassionate_Care_Pilot_Results.pdf

- End-of-Life Care Survey of Upstate New Yorkers: Advance Care Planning Values and Actions Summary Report. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: http://www.compassionandsupport.org/pdfs/research/End_of_Life_survey-EX.pdf

- Excellus BlueCross BlueShield. 2014. Employee Health Care Proxy Completion Rates, 2002-2014. [accessed 2015 Feb 2]. Available online: http:// www.compassionandsupport.org/pdfs/news/NHDD2014datacomparison.pdf

- Rao JK, Anderson LA, Lin FC, et al. Completion of advance directives among U.S. consumers. Am J Prev Med 2014;46:65-70. [PubMed]

- Fagerlin A, Schneider CE. Enough. The failure of the living will. Hastings Cent Rep 2004;34:30-42. [PubMed]

- Gillick MR. Advance care planning. N Engl J Med 2004;350:7-8. [PubMed]

- Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Perrin NA, et al. A comparison of methods to communicate treatment preferences in nursing facilities: traditional practices versus the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment program. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1241-8. [PubMed]

- Teno JM, Licks S, Lynn J, et al. Do advance directives provide instructions that direct care? Support Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 1997;45:508-12. [PubMed]

- National Quality Forum (NQF) A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality. [accessed 2014 Dec 2]. Available online: http://www.qualityforum.org/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?LinkIdentifier=id&ItemID=22041

- Bomba PA, Caprio TV, Gillespie SM, et al. Community implementation of the Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST) to improve advance care directives. J Am Ger Soc 2007;55:S44.

- Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST) Poster presented at the BlueCross BlueShield Association Conference in October 2008. [accessed 2015 Feb 9]. Available http://www.compassionandsupport.org/pdfs/MOLST-poster.pdf