Efficacy and safety of Kanglaite injection combined with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with advanced NSCLC: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 32 RCTs

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer. According to global cancer statistics, lung cancer was the leading cancer-related death in 2018 (1), with 80% of these cases being non-small cell lung carcinomas (NSCLC). Even with this well-known mortality, over 50% of NSCLC present with advanced local invasion and metastasis during hospital admission diagnosis, meaning they have missed the opportunity for surgical intervention. Despite the promising emergence of molecular targeted therapy and immunotherapy, platinum-based chemotherapy is still the cornerstone of NSCLC treatment, especially for advanced stages III and IV of the disease (2). First-line platinum-based chemotherapy, including cisplatin or paraplatin plus vinorelbine, paclitaxel, gemcitabine, docetaxel, or pemetrexed (3), is widely used in advanced NSCLC. However, adverse reactions, including nausea and leukopenia, are frequently reported (4,5).

In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) basic theory, lung cancer is nearly equivalent to the domains of “mass” or “phlegm and dampness”, which is acknowledged to be one of the basic pathogeneses. Kanglaite injection (KLT) (Z10970091, China Food and Drug Administration) is extracted from the seeds of the Chinese medicinal herb (CMH) Coix lacryma-jobi, whose anticancer effect thought treating the dampness with bland and treat “mass” in traditional Chinese medicine theory. Past studies have suggested that KLT is a micro-emulsion for intravenous use that demonstrates antitumor efficacy, improves the quality of life (QOL), and reduces toxicity (6,7). However, the outcome of its combination with different chemotherapy regimens and the long-term synergistic efficacy is still unclear. Moreover, CMH is often considered to have serious adverse reactions (8), and the Chinese government has announced a post-marketing review of TCM injections in the following 5 to 10 years (9). Finally, the exact effect and survival rate after the application of KLT are also a concern.

This systematic review and meta-analysis were performed to compare KLT plus first-line platinum-based chemotherapy with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy alone in patients with advanced NSCLC by the using tumor response and adverse reactions as outcome measures. We present the following article following the PRISMA 2009 reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-616).

Methods

This article follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA guidelines), and the study is registered with PROSPERO (CRD 42019142414). As a systematic review and meta-analysis, Ethical approval was not required as materials of this study had been published.

Data sources

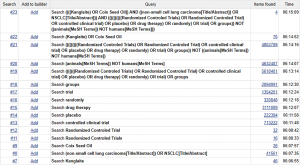

Two reviewers (Juan Li and Hong-Zheng Li) independently searched for and extracted information from randomized clinical trials (RCTs) related to KLT-assisted treatment of NSCLC. RCTs were searched for in Chinese and English databases, including the PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Web of Science (ISI), Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Scientific Journals Full-Text Database (VIP), CBM, and Wanfang databases. The searches were restricted to original publications from the time of establishment to December 1, 2019. A combination of the following keywords was used: “lung cancer”, “lung carcinoma”, “non-small cell lung cancer”, “non-small lung carcinoma”, “NSCLC”, “Kanglaite”, “KLT”, and “Coix Seed Oil”. All retrievals were implemented using the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free word. Finally, all related systematic reviews (SRs) and meta-analyses were evaluated, and studies meeting the inclusion criteria were selected from the references. As an example, the electronic strategy for PubMed can be seen in Figure S1.

Search strategies and selection criteria

Trials were selected on the following inclusion criteria: (I) the trial was an RCT. (II) The patients were diagnosed with NSCLC stages III to IV, according to histopathological and cytological diagnostic criteria. (III) The experimental group had undergone KLT (Z10970091, China Food and Drug Administration) plus first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, and the control group had undergone first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. First-line platinum-based chemotherapy refers to cisplatin or paraplatin plus vinorelbine, paclitaxel, gemcitabine, docetaxel or pemetrexed (NP, TP, GP, DP, and AP, respectively). (IV) Patients did not receive any radiotherapy, other chemotherapy, or Chinese herbs during this study. (V) The outcome needed to include at least an objective response rate (ORR) or adverse reactions (nausea and vomiting, leukopenia). Exclusion criteria were (I) duplicates (797 studies); (II) unrelated studies including other treatments (56 studies); (III) non-RCTs including case-control studies and series case reports (23 studies); (IV) abstracts and reviews without specific data and unrelated SRs (59 studies), and (V) studies with no ORR or adverse reaction (nausea and vomiting) data (17 studies).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two researchers (Juan Li and Guang-Hui Zhu) independently extracted the following information from each study: the lead author; the publication time; the demographic characteristics; the sample size; the usage of KLT and the types of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy; the evaluation criteria of clinical efficacy; and whether supportive treatment including anti-nausea drugs, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) were administered. Furthermore, outcomes including the ORR, leukopenia, nausea and vomiting, median survival time (MST), disease control rate (DCR), and Karnofsky performance status (KPS) were examined. The data were obtained directly from the articles. A third reviewer resolved any disagreements (Jie Li).

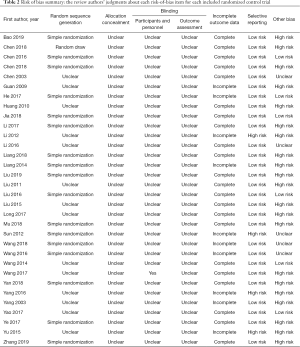

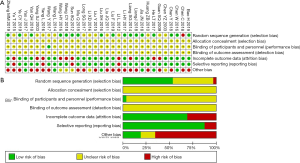

The methodological quality of the included RCTs was assessed independently by two researchers (Hong-Zheng Li and Guang-Hui Zhu) on the Cochrane risk-of-bias criteria (10) using the following parameters to evaluate the bias risk: random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective reporting (reporting bias), and other bias (whether the baseline is comparable). Subsequently, the trials were assessed and categorized into three levels: low risk (all items were “yes”), high risk (at least one item was “no”), and unclear risk (at least one item was “unclear”).

Main outcomes

We measured the tumor response using the ORR. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for solid tumor responses (11) or Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) (12), indicators were complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), progressive disease (PD), with ORR being equal to CR plus PR. Adverse reactions (adverse drug events or adverse drug reactions) were pooled, including nausea and vomiting, and leukopenia.

Secondary outcomes

The long-term synergistic efficacy of this combination was considered MST. Also, the secondary outcomes included DCR and QOL. QOL was considered improved if the KPS score increased by 10 points or higher after treatment (13). DCR was calculated as CR plus PR and SD.

Statistical analysis

Two reviewers performed the meta-analysis (Juan Li and Guang-Hui Zhu) using Review Manager 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) and Stata 15.1. The relative risk (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. Statistical heterogeneity of the results across trials was assessed by a Chi-square based Q-statistic test, and the consistency was calculated by I2. If the homogeneity (P≥0.1, I2≤50%) was not rejected, the fixed-effects model (FEM) was used to calculate the summary RR and the 95% CI. Alternatively, the results were calculated by the random-effects model (REM). We performed a subgroup analysis according to different doses of KLT, types of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, the cycle of chemotherapy, and evaluation criteria, which revealed their influence on tumor responses.

Furthermore, we performed a subgroup analysis regarding using supportive treatment for adverse reactions. Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots if more than 10 included studies were included. Subgroup analyses were performed following the doses of KLT, the type, and cycle of chemotherapy, supportive treatment, and evaluation criteria to reveal the clinical heterogeneity and its influence on the endpoint.

Results

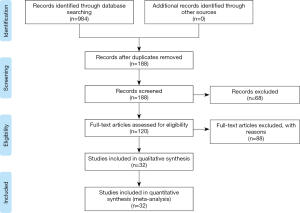

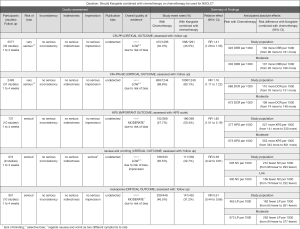

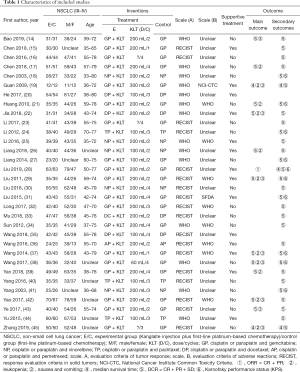

The literature search identified 188 studies and excluded 68 after careful screening of titles and abstracts. The full text of the 120 remaining studies was assessed for eligibility, and 88 were excluded because they were reviews, did not contain eligible comparators, did not report outcomes of interest, were case series, or for other reasons (Figure 1). Finally, 32 articles comprising 2,577 patients met the inclusion criteria and were retrieved for quantitative synthesis, with all the records being studied in China (Table 1).

Full table

Characteristics of eligible studies

The experimental group comprised 291 cases of KLT plus first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, while the control group comprised 1,286 cases of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy alone. There were 1,436, and 989 males and females included respectively, with age ranging between 32 and 80 years. The dosage of KLT was 60 to 300 mL/day, and the treatment time was 3 to 4 weeks/cycle, with 1 to 4 cycles of intravenous injection. According to the WHO guidelines for solid tumor responses (11) or RECIST (12), tumor responses were evaluated in 32 studies (14-29) involving 2,577 patients (30-45). Nausea and vomiting were evaluated in 9 studies (14,19,22,29,37,38,42,43,45) involving 692 patients, and leukopenia was evaluated in 11 studies (17,19,21,22,26,29,37-39,42,45) involving 901 patients. According to the WHO standards (11) or National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC) (46), 4 studies for nausea and 5 studies for leukopenia were included.

Methodological quality

All studies mentioned randomization, with only 17 studies (14,16,17,20,22,23,26-28,30,33-36,39,43,45) reporting the details of the randomized methods, and none reporting the details of concealed allocations. One study (38) revealed the blinding methods but not the details regarding the blinding of patients or assessors. Additionally, one study (33) revealed that all the participants were aware of the treatment in advance, which did not affect the outcome.

Fourteen participants withdrew from three studies (27,36,41), with five presenting acute/subacute toxicity, five participants were treated with another treatment, and four participants withdrew for personal or economic reasons. Furthermore, seven studies lacked outcome data (19,20,24,34,35,40,44). Three studies selectively reported acute/subacute toxicity (34,40,44), with one reporting KPS (33). The methodological bias risk of all included studies is presented in Table 2 and Figure 2.

Full table

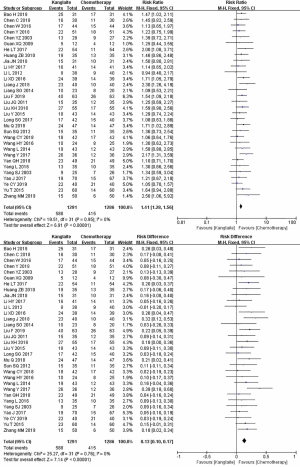

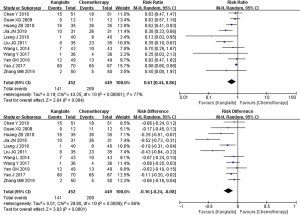

ORR

The reporting of ORR occurred in 32 studies (14-29) comprising 2,577 cases (30-45) (Figure 3). Pearson’s Chi-square test and I2 test indicated the absence of statistical heterogeneity among studies (I2=0%). The ORR in the meta-analysis demonstrated statistical differences between KLT plus first-line platinum-based chemotherapy and first-line platinum-based chemotherapy alone (RR =1.41, 95% CI: 1.28 to 1.56, ARD =0.13, 95% CI: 0.1. to 0.17, and P<0.00001) by FEM.

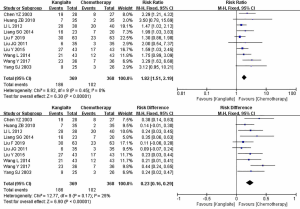

Adverse reactions

A high heterogeneity was observed among studies regarding nausea and vomiting (I2=64%) (Figure 4) and leukopenia (I2=77%) (Figure 5). The meta-analysis revealed that KLT plus first-line platinum-based chemotherapy involved a lower risk of nausea and vomiting (RR =0.58, 95% CI: 0.42 to 0.81, ARD =−0.17, 95% CI: −0.26 to −0.08, and P=0.001) and leukopenia (RR =0.61, 95% CI: 0.44 to 0.86, ARD =−0.16, 95% CI: −0.24 to −0.08, and P=0.004) than the first-line platinum-based chemotherapy alone using REM. Furthermore, all differences were statistically significant.

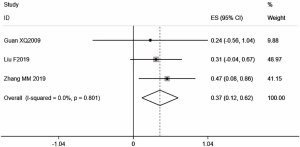

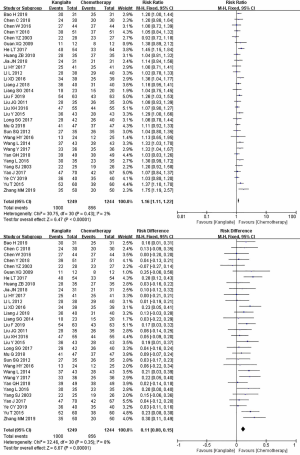

Effects on secondary outcomes

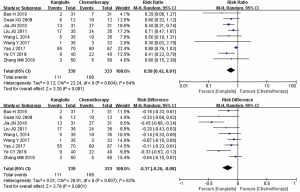

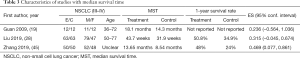

For secondary outcomes, 3 studies with 243 cases (19,28,45) mentioned the average value of MST (Figure 6, Table 3), while 10 studies with 899 cases (18,21,24,27,29-31,37,38,41) reported the KPS scale evaluated by QOL (Figure 7). DCR was reported in 31 studies with 2,493 cases (Figure 8). Minimal heterogeneity was observed among studies in MST (I2=0%), KPS (I2=0%), and DCR (I2=2%). Meta-analysis demonstrated that MST (HR =0.37, 95% CI: 0.12 to 0.62), QOL (RR =1.82, 95% CI: 1.51 to 2.19, ARD =0.23, 95% CI: 0.16 to 0.29), and DCR (RR =1.16, 95% CI: 1.11 to 1.22, ARD =0.11, 95% CI: 0.08 to 0.15) indicated statistical differences between the two groups by FEM.

Full table

Subgroup analysis

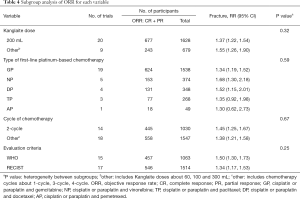

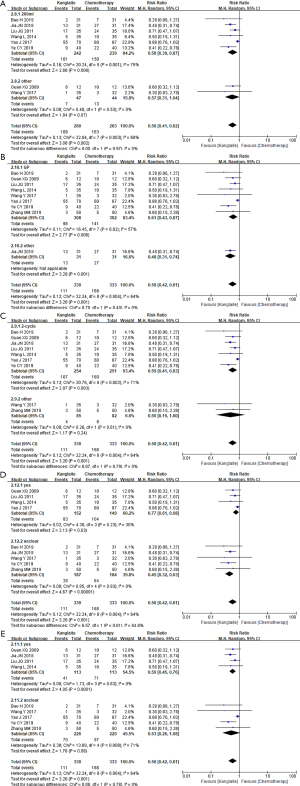

Subgroup analysis of ORR

Subgroup analysis was performed to reveal the influence of different doses, types of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, cycles of chemotherapy, and evaluation criteria on the ORR (Table 4 and Figure S2A,B,C,D). Drug doses included 200 mL on the KLT medicine instruction (47) and other doses. Subgroup analysis indicated that both doses increased the ORR. Types of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy included cisplatin or paraplatin plus vinorelbine, paclitaxel, gemcitabine, docetaxel, or pemetrexed (NP, TP, GP, DP, and AP). Subgroup analysis demonstrated that only KLT plus GP, NP, and DP could increase the ORR. The differences between TP (P=0.12) and AP (P=0.49) were not statistically significant. The chemotherapy cycles included 2 cycles and more, and both cycles could increase the ORR. Tumor responses were evaluated using WHO or RECIST criteria. Subgroup analysis showed that KLT plus first-line platinum-based chemotherapy could increase the ORR using the WHO or RECIST criteria.

Full table

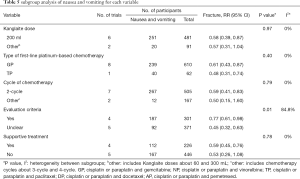

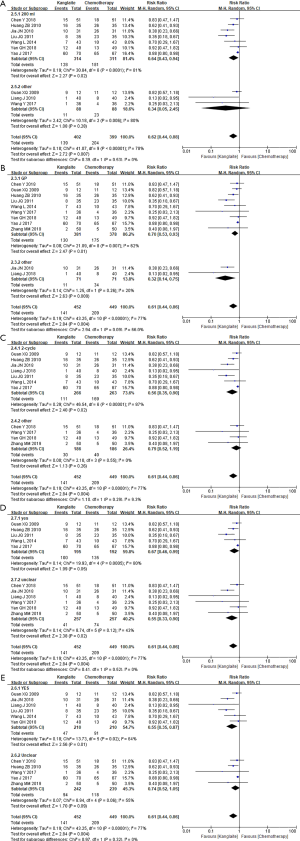

Subgroup analysis of nausea and vomiting

Subgroup analysis was performed to reveal the influence of different doses, types of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, cycles of chemotherapy, evaluation criteria, and supportive treatment for nausea and vomiting (Table 5 and Figure S3A,B,C,D,E). The subgroup analysis failed to find any significant differences among the subgroups on the dose of KLT, chemotherapy types, chemotherapy cycles, and supportive treatment. Furthermore, the other doses (P=0.07), other cycles (P=0.24), and unclear supportive treatment (P=0.08) were not statistically significant. Additionally, high subgroup differences regarding evaluation criteria (I2=84.8%, P=0.01) were observed.

Full table

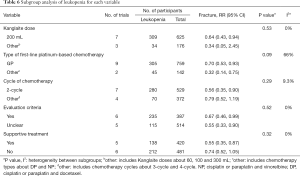

Subgroup analysis of leukopenia

The subgroup analysis failed to report any significant differences among subgroups on the dose of KLT, chemotherapy cycles, evaluation criteria, and supportive treatment for leukopenia (Table 6 and Figure S4A,B,C,D,E). Additionally, other doses (P=0.28), other cycles (P=0.26), and unclear supportive treatment (P=0.09) were not statistically significant, but high subgroup differences regarding chemotherapy types (I2=66%, P=0.09) were noted.

Full table

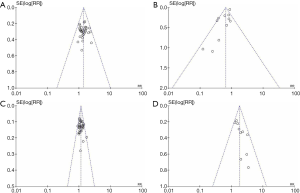

Publication bias analysis (Figure 9)

The funnel plots were symmetric in ORR, DCR, and KPS (Figure 9A,C,D). Furthermore, no publication bias was observed in studies that objectively reported the results. The funnel plots were asymmetric in leukopenia (Figure 9B). These results indicated publication bias. Leukopenia was overestimated in one study (42).

Summary of evidence

We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) to report the quality of evidence for ORR, DCR, KPS, and adverse events. The quality of evidence was rated as high, moderate, low, and very low, and the results revealed a moderate or low overall quality (Figure S5).

Discussion

As a traditional Chinese medicine injection, KLT is widely used in clinical patients with lung, gastric, and liver cancer (48,49) as an adjunct to chemotherapy for improving the curative effect. Some studies have shown that KLT can sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy (50,51). One network meta-analysis (52) that included three traditional Chinese medicine injections showed KLT combined with NP had the greatest efficacy in ORR, ranking first with a probability of 71%.

Summary of the results

In our study, KLT plus first-line platinum-based chemotherapy improved the ORR and decreased the risk ratio of nausea, vomiting, and leukopenia in NSCLC. We observed significant clinical heterogeneity in adverse reactions, which is consistent with previous studies (7). However, previous studies failed to explain the long-term synergistic efficacy of this combination and did not perform subgroup analysis to clarify the observed clinical heterogeneity. Our subgroup analysis indicated these results were generally consistent regardless of the dose of KLT, chemotherapy cycles, and evaluation criteria for ORR. Regarding the type of chemotherapy, there were no significant differences between KLT combined with TP or AP. We did not reach any definite conclusions about AP due to only one relevant study being available. There were three studies in the TP subgroup and showed no obvious quality problems of ORR. Ma observed that the inhibitory effect of KLT plus TP in Lewis lung cancer cell lines was not significantly different from TP (53). Previous studies have reported KLT plus paclitaxel demonstrated no significance compared to paclitaxel in advanced malignant thymoma (54). Aside from insufficient quantity, we assumed KLT combined with GP, NP, and DP, but not TP, could increase tumor responses. We applied the KPS scale to evaluate the QOL and observed that KLT significantly increased the KPS.

Furthermore, a meta-analysis with 31 studies showed that KLT could slightly increase the DCR. Therefore, we believe KLT plus first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, excluding the TP combination, could significantly increase clinical efficacy. The results indirectly indicate KLT may have a synergistic efficacy with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy.

First-line platinum-based chemotherapy demonstrates varying degrees of blood and gastrointestinal toxicity, and we selected the most common clinical adverse reactions, including nausea, vomiting, and leukopenia, to evaluate the role of KLT in preventing adverse reactions. For nausea and vomiting, further subgroup analysis indicated that clear evaluation criteria were the source of heterogeneity. For leukopenia, further subgroup analysis showed that variability in chemotherapy type was the source of heterogeneity, and leukopenia was overestimated in one study (41). It is worth mentioning that using use of supportive treatment during KLT plus first-line platinum-based chemotherapy would not decrease the risk ratio of both adverse reactions compared with chemotherapy alone, which has not been mentioned in previous studies (48,55). However, there are many factors in clinical settings, including supportive treatment, treatment dosage, type of chemotherapy. Hence, we assumed an indefinite conclusion regarding the role of KLT in the matter.

Strengths and limitations

This is the most detailed meta-analysis focusing on the efficacy of ORR, KPS, and adverse reactions, and can thus better inform the clinical application of KLT. However, some limitations this study should be noted. First, only Chinese and English databases were searched, and some relevant studies might have been excluded due to language restrictions. Furthermore, all of the included studies were published in China, which might have led to publication bias. Secondly, only 17 studies reported the random allocation methods, but no study provided detailed information on the random allocation concealment.

Moreover, 14 participants withdrew from the clinical study with 5 reporting acute/subacute toxicity; this could have influenced the outcome of adverse reactions. Additionally, three studies demonstrated selective reporting concerning acute/subacute toxicity, and 1 study did so concerning KPS. Thirdly, the methods used to classify studies as high quality might have been relatively lenient, and other researchers may have selected different definitions for study quality.

Suggestions for future clinical trials

Differences in survival rates are of utmost importance to clinicians and NSCLC patients alike. We are similarly interested in the long-term synergistic efficacy of KLT plus first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, particularly as it relates to survival and deterioration rate effect. In our meta-analysis, three studies (19,28,45) mentioned MST, and the combined treatment showed a positive effect on MST compared with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy merely. We noticed that evidence concerning long-term synergistic efficacy, such as overall survival and progression-free survival, was still insufficient. Apart from that, we noticed that some studies demonstrated the survival rate using a life table to show the changes vividly, but only complete reporting may bring meaningful work to NSCLC treatment. Therefore, we appeal to clinical researchers to include short-term and long-term synergistic efficacy with the specific normative data type and regard it as a vital outcome in further research.

Conclusions

The evidence indicates KLT plus first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, except the combination with TP, may significantly improve the clinical efficacy in patients with advanced NSCLC. With supportive treatments, this combination demonstrated a lower risk of nausea, vomiting, and leukopenia, and positively affected MST and KPS. These results indicate KLT may indirectly have ameliorative and synergistic efficacy with first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. Finally, many shortcomings in clinical trial methodology resulted in an inadequate assessment of clinical efficacy and safety. We are thus eager to evaluate larger-scale RCTs or real-world studies to present an in-depth review in the near future.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Session of Evidence-based Clinical Club (EBC) for the direction on the manuscripts.

Funding: This work was financially supported by National key research and development plan of China (No. 2018YFC1707405) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81774289, 81473463). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA 2009 reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-616)

Data Sharing Statement: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-616

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-616

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-616). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. As a systematic review and meta-analysis, Ethical approval was not required as materials of this study had been published.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018;68:394-424. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wakelee H, Kelly K, Edelman MJ. 50 Years of progress in the systemic therapy of non-small cell lung cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2014.177-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 3. 2019. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals. Accessed 18 Jan. 2019. In.

- Rossi A, Di Maio M. Platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: optimal number of treatment cycles. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2016;16:653-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dasari S, Tchounwou PB. Cisplatin in cancer therapy: molecular mechanisms of action. Eur J Pharmacol 2014;740:364-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pan P, Wu Y, Guo ZY, et al. Antitumor activity and immunomodulatory effects of the intraperitoneal administration of Kanglaite in vivo in Lewis lung carcinoma. J Ethnopharmacol 2012;143:680-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Xu F, Wang G, et al. Kanglaite injection plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for non-small cell lung cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp 2008;69:381-411. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qin Y. Opinions on deepening the reform of review and approval system to encourage the innovation of medical devices. Chinese Journal of Medical Management 2017;25:190.

- Ji K, Chen J, Li M, et al. Comments on serious anaphylaxis caused by nine Chinese herbal injections used to treat common colds and upper respiratory tract infections. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2009;55:134-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higgins GS. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. Available online: http://training.cochrane.org/handbook

- Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, et al. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer 1981;47:207-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Watanabe H, Yamamoto S, Kunitoh H, et al. Tumor response to chemotherapy: The validity and reproducibility of RECIST guidelines in NSCLC patients. Cancer Science 2003;94:1015-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zheng X. Guiding principles for clinical research of new Chinese medicine (trial). Beijing: China Medical Science and Technology Press 2002:216-21.

- Bao H, Ma N, Qin N. Clinical Efficacy and Safety Evaluation of Kanglaite combined with Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in the Treatment of Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Special Health 2019;(20):66-7.

- Chen C. Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Randomized Parallel Controlled Study of Advanced Kanglaite Injection combined with GP in Treatment. Journal of Practical Traditional Chinese Internal Medicine 2018;32:46-8.

- Chen W, Wei T. Clinical Effect and the Influence on Immune Function of Kanglaite Injection combined with Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in the Treatment of Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Chinese Journal of Clinical Oncology and Rehabilitation 2016;23:814-7.

- Chen Y. Effect of GP Regimen combined with Kanglaite in the Treatment of Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Medical Journal of Chinese People's Health 2018;30:73-5.

- Chen Y, Li P, Yang L, et al. Effect of Kanglaite Injection combined with Navelbine plus Cisplatin in the Treatment of Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine 2003;08:629-60.

- Guan X, Liu J, Li L. Clinical Observation of Coix Seed Oil for Injection combined with GP Regimen in the Treatment of Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Chinese Journal of Postgraduates of Medicine 2009;32:60-2.

- He L, Wu X, Yu X, et al. Clinical Effect and Quality of Life of Patients with Advanced Lung Cancer Improved by Kanglaite Injection. Modern Practical Medicine 2017;29:329-30.

- Huang Z, Zhu C, Wu S. Effect of Kanglaite Combined with Chemical Therapy Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. China Pharmacy 2010;21:1860-1.

- Jia J. Effect of Kanglaite Injection on Immune Function and Adverse Reactions in Advanced NSCLC Patients with Chemotherapy. Journal of Community Medicine 2018;16:11-3.

- Li H. Clinical Effect of Kanglaite Injection Combined with Gemcitabine and Cisplatin on Advanced Non-small-cell Lung Cancer and the Impact on Immune Function. Practical Journal of Cardiac Cerebral Pneumal and Vascular Disease 2017;25:121-3.

- Li L, Dai F, Ma Y, et al. Observation of Kanglaite Injection on the Quality of Life of Elderly Patients with Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Hebei Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2012;34:1691-2+1718.

- Li X, Dong L. Effect of Kanglaite Injection Combined with Chemotherapy on the Quality of Life and Arrest of bone Marrow in Patients with Advanced Non-small Cell lung Cancer. Hebei Medicine 2016;22:543-5.

- Liang J, Cai H, Chen Z. Effects of Kanglaite Injection Adjuvant NP Chemotherapy on Lung Cancer. Journal of Gannan Medical University 2018;38:232-5.

- Liang S, Dong Y, Wang J, et al. Kanglaite Combined with GP in the Treatment of 25 cases of Senile Non-small-cell Lung Carcinoma. China Journal of Chinese Medicine 2014;29:11-2.

- Liu F. Clinical Observation on the Treatment of Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer by Kanglaite combined with GP. Research of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine 2019;11:36-8.

- Liu J, Shang L, Li X, et al. Effect of kanglaite combined with Chemical Therapy Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Modern Oncology 2011;19:1974-6.

- Liu X, Wang W. Effect of Kanglaite Injection in the Treatment of Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer and Its Effect on Immune Function. Shanxi Medical Journal 2016;45:1211-3.

- Liu Y, Ma P. Therapeutic Effect of Kanglaite Injection combined with Gemcitabine and Cisplatin on Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Chinese Journal of Practical Medicine 2015;42:43-5.

- Long S, Xiao Y. Clinical Efficacy of Kanglaite combined with GP Regimen in Patients with Advanced NSCLC and Its Effect on Various Indexes of Immune Function. Anti-Infection Pharmacy 2017;14:377-80.

- Mu Q, Li Y. Effects of Kanglaite Injection combined with DC Chemotherapy on Serum T cell Subsets and Quality of Life in Patients with Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Journal of Medical Forum 2018;39:120-1.

- Sun S, Zhu X, Huang J, et al. Effect of Kanglaite Injection combined with Chemotherapy for Improvement of Quality of Life in Advanced Stage NSCLC Patients. Journal of Practical Oncology 2012;27:506-10.

- Wang C, Wang C. Clinical Observation of Kanglaite Injection combined with Docetaxel Cisplatin in the Treatment of Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Chinese Remedies & Clinics 2018;18:989-91.

- Wang H, Tang H, Wu Y, et al. Synergistic Effect of Kanglaite Injection combined with Pemetrexed and Cisplatin in the Treatment of Advanced Lung Adenocarcinoma. China Medical Herald 2016;13:138-41.

- Wang L. Effects of Kanglaite Adjuvant Chemotherapy on Immune Function of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer and Clinical Efficacy Analysis. Laboratory Medicine and Clinic 2014;11:1072-3+1075.

- Wang Y, Hui S, Li M, et al. Clinical trial of Kanglaite Injection in Gemcitabine combined Cisplatin Regimen Chemotherapy for Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. The Chinese Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2017;33:2354-6+2360.

- Yan Q, Xing G, Pan Q. Effect Observation of GP Regimen combined with Kanglaite in the Treatment of Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Practical Clinical Journal of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine 2018;18:112-3+121.

- Yang L, Yang X. Effects of Kanglaite Injection on the Improvement of Symptoms and Quality of Life in Patients with Advanced Lung Cancer. Health Research 2016;36:446-7.

- Yang S, Yao Y, Li Y, et al. Clinical Observation on the Treatment of Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer with Kanglaite Injection combined with Chemotherapy. Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Western Medicine 2003;08:629.

- Yao J, Song X. Efficacy and Safety Analysis of GP Scheme combined with Kanglaite Injection for Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Exp Med 2017;16:1195-8.

- Ye C, Zhao F, Xing S, et al. Clinical Observation of Kanglaite Injection Combined with Gemcitabine Cisplatin Regimen for Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin Res 2019;27:24-6.

- Yu T, Zhang Q, Qi Y. Improvement of Kanglaite on the Symptoms and Quality of Life in Advanced Lung Cancer Patients. China Pharmaceuticals 2015;24:29-31.

- Zhang M. Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Kanglaite Injection in Patients with Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. The Journal of Medical Theory and Practice 2019;32:54-6.

- Trotti A, Colevas D, Setser A, et al. Patient reported outcomes and the evolution of adverse event reporting in oncology. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5121-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhejiang Kanglaite Pharmaceutical Co. LTD, Kanglaite Injection Medicine Instruction, 2010 version.

- Fu F, Wan Y. Kanglaite injection combined with hepatic arterial intervention for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Ther 2014;10:38-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qi F, Li A, Inagaki Y, et al. Chinese herbal medicines as adjuvant treatment during chemo- or radio-therapy for cancer. BioScience Trends 2010;4:297-307. [PubMed]

- Yang C, Hou A, Yu C, et al. Kanglaite reverses multidrug resistance of HCC by inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest via PI3K/AKT pathway. Onco Targets Ther 2018;11:983-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Zhang C, Zhang S, et al. Kanglaite sensitizes colorectal cancer cells to Taxol via NF-κB inhibition and connexin 43 upregulation. Sci Rep 2017;28;7:1280.

- Wu Z, Lin S, Luo Q, et al. Evidence-based pharmacoeconomic evaluation of NP regimen assisted by traditional Chinese medicine injection in the treatment of elderly non-small cell lung cancer. Chinese J Exp Traditional Medical Formulae 2015;21:199-202.

- Ma W, Wang R, Wu Y, et al. Experimental study on the inhibitory effect of paclitaxel, cisplatin and kanglaite on Lewis lung cancer cell line. Chinese Journal of Medical Guide 2012;14:863-5.

- Xia L, Tang S. Effect of kanglaite injection combined with paclitaxel in the treatment of advanced malignant thymoma. Journal of Modern Oncology 2019;27:1750-3.

- Chen Z, Lin R, Sun L, et al. Kanglaite injection combined with chemotherapy on quality of life for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A Meta-analysis. Chinese Journal of Surgical Oncology 2019;11:183-189+194.