Palliative care and advance care planning for patients with advanced malignancies

Introduction

Approximately 1.7 million people in the United States are diagnosed with cancer annually and despite the development of novel cancer therapies, an estimated 600,000 die from cancer each year (1). Of these deaths, most are due to metastatic or recurrent disease. Most metastatic or recurrent cancers are not curable and treatment is administered with the goal of controlling the growth of the cancer and relieving symptoms (1). Therefore, patients facing a diagnosis of advanced cancer need to have an honest understanding of their medical plan of care and require support and encouragement in discussing and documenting their own treatment preferences. These aspects of care are key components of advance care planning (ACP).

National guidelines recommend ACP with discussions about palliative care and hospice for patients who have a life expectancy of less than 1 year (2,3). ACP allows patients to: have clear expectations of their treatment course and physical condition, specify a health care proxy with whom they have discussed their own wishes, document their own treatment preferences and discuss death and dying comfortably with their physician (4).

Unfortunately, many studies have demonstrated that all too frequently patients with advanced cancer have not had meaningful ACP discussions early enough in their clinical course. As a result many patients do not have a clear understanding of their prognosis (5-7) and opt for aggressive treatments that have little or no hope for cure (8). This frequently results in patients having poorly controlled symptoms and insufficient patient and family support (9). Processes to improve upon ACP emphasize symptom management and communication, providing patients and their families with a sense of peace and control at the end-of-life (10). These processes are highly individualized, vary between patients and within family members and care providers, and require a specialized, patient-centered approach to care (10).

Palliative care has been defined by the World Health Organization as “an approach (to care) that improves the quality of life of patients and their families… by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual” (11). Palliative care provides relief from distressing symptoms, affirms life and regards dying as a normal process while intending neither to hasten or postpone death (11) and can therefore play a prominent role in ACP discussions for patients and families with advanced cancers. This review details the importance of ACP and demonstrates the role of palliative care specialists in early communication with patients with advanced cancer.

Importance of ACP

Unfortunately, there continues to be a general reluctance from physicians caring for patients with cancer to initiate ACP early. Some studies have shown that fewer than 40% of patients with advanced cancer have had advance care discussions with a physician (12,13). A majority of physicians reported that they would not discuss ACP with patients with incurable disease who are feeling well. Instead this group reported they would wait for significant symptoms to be present or until there were no available treatment options (14). Hospital admissions have been shown to be a trigger for ACP discussions, with one study revealing that the majority (55%) of end-of-life discussions took place in the hospital (15). A change in a patient’s resuscitation status from ‘full code’ to ‘do not resuscitate’ suggests that some form of advance care discussion occurred. As further emphasis that hospitalization is frequently what prompts ACP discussions, a study of 200-consecutive deaths in a general hospital, revealed that 13% of patients had a DNR order at the time of admission. This number increased to 77% at the time of death and 90% of patients who were hospitalized for more than 3 weeks had a documented DNR order (16). Patients with advanced cancer who suffer from in-hospital cardio-pulmonary arrest have a very low survival rate following cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) (17). Delayed ACP places patients at risk of receiving aggressive end-of-life care and interventions that have a very low likelihood of prolonging their life.

Resuscitation preferences are one aspect of ACP. Given that most patients with advanced cancer who require in-hospital CPR do not survive, many studies have focused on physician or patient interventions at improving documentation of resuscitation status. One study utilized electronic-mail prompts to encourage oncologists to document patient’s resuscitation preferences. At 1-year follow-up, significantly more patients (34% compared to 15%) whose oncologists had received electronic prompts had a documented code status. The average time to code status documentation was also significantly shorter in the group whose physicians received electronic prompts (8.6 months compared to 10.5 months) (18). The patient decision aid “Living with Advanced Cancer” was shown to improve earlier placement of DNR orders relative to the time of death and decrease the likelihood of death in the hospital (19). A study of patients with malignant glioma studied the role of a goals-of-care video supplement to a verbal conversation in improving end-of-life decision making for patients with cancer. Amongst those patients who viewed the supplemental video, none preferred life-prolonging care (CPR and ventilation), compared to 26% of those patients who received only a verbal description (20). Other studies with informational videos depicting CPR, similarly have shown a reduction in the number of patients with advanced cancer opting for CPR (20,21). As a whole these studies make a compelling argument for the development of targeted interventions aimed at both patients and providers to increase discussions and documentation of patient’s end-of-life preferences.

Significant deficiencies in physician-patient communication have been noted. In a study of 9,000 patients hospitalized with life threatening diagnoses, only 47% of physicians knew when their patients preferred to avoid CPR (22). Another study of 1,500 patients with metastatic lung cancer revealed that only half of the patients had discussed hospice with their physicians within 4 to 7 months of diagnosis (23). These studies highlight important aspects of ACP and end-of-life care options and demonstrate that they are either not being discussed or being discussed late in the disease course.

The trend in end-of-life care has been toward increasingly aggressive care. Quantification of Medicare claims for approximately 28,000 patients who died within 1 year of a diagnosis of lung, breast or gastrointestinal cancer revealed that from 1993 to 1996, there was a statistically significant increase in the percentage of patients receiving chemotherapy within 2 weeks of death (13.8% to 18.5%) (24). During this same period, there was also an increase in the number of patients with emergency room visits in the last month of life (7.2% to 9.2%), number of patients with hospital admissions (7.8% to 9.1%), and the number of patients treated in the intensive care unit (9.9% to 11.7%) (24). Although patients are getting more aggressive treatment, this does not appear to translate into an improved quality of life or longer survival (12).

Challenges for ACP

Most patients with advanced cancer prefer to receive truthful and timely information about their illness. Studies have demonstrated that 96% of patients believed they should be informed of their terminal illness, and 72% felt that they should be informed immediately after the diagnosis (25). Most patients also want to be involved in medical decision-making. A study specifically examining the decisional role in patients with breast cancer at the time of surgery, demonstrated that those women who indicated that they were actively involved in choosing their treatment had a significantly higher overall quality of life at follow-up than those who indicated they assumed a passive role (26). Empowering patients to be engaged in decision making requires that they have an accurate understanding of treatment options and prognosis (27-29).

Patients’ understanding of their own life expectancy is frequently discordant with their physician’s expectation. One study demonstrated that of 520 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, 82% and 75% of patients respectively believed that their chance of 2- and 6-month survival was greater than or equal to 90%, whereas 22% and 5% of physicians respectively held these beliefs (5). Other studies have similarly shown that a large proportion of patients with incurable cancer have unrealistic expectations with regard to their own life expectancy (6,7). In parallel with these conflicting expectations of life expectancy is an inaccurate understanding of the potential benefit of treatments for incurable cancer. In a recent study the majority of patients with incurable cancer did not understand that chemotherapy was not likely to cure their cancer (8). Patients who overestimate their survival seem to prefer more aggressive treatment (12). An inaccurate understanding of prognosis and the role of specific therapies may compromise patient’s ability to make informed treatment decisions (8), further emphasizing the need for accurate physician-patient communication regarding prognosis.

A recent prospective cohort trial evaluated the association between ACP and aggressiveness of care for patients with incurable cancer at the end-of-life. This study looked at 1,200 patients with metastatic lung or colorectal cancer. Patients who engaged in end of life discussions with their physician before the last 30 days of life were significantly less likely to receive aggressive measures at the end-of-life, including chemotherapy and acute care (30). Importantly, ACP and discussions about end-of-life care have not been associated with higher rates of major depressive disorder or increased worry. Rather, these conversations have been shown to be associated with lower rates of ventilation, cardiac resuscitation and intensive care unit admissions, essentially all forms of aggressive care. More aggressive care has been associated with worse patient quality of life and higher risk of major depressive disorder and prolonged grief disorder in bereaved caregivers (12,31). Taken together, these data suggest that early advance care planning for patients with advanced cancer may allow patients and their families to consider personal goals and make treatment decisions accordingly.

Recommendations for ACP

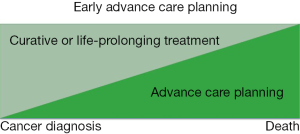

There is no standardized approach to ACP for patients with advanced cancer because individual patient and family needs vary widely. However, there has been increasing emphasis on ACP early in the course of a serious illness (Figure 1). General guidelines recommend that ACP discussion occur early in the disease course for patients with incurable cancers with physicians who know the patient well (9,10,32). National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines specifically recommend that oncologists “initiate discussion of personal values and preferences for end-of-life care” when patients have an estimated life expectancy of months to years (2). They emphasize that ACP should include a discussion of patient values and care preferences, patient, family and care team wishes and expectations, and information about advance directives and palliative care options. The values and preferences identified should be documented in the medical record (2).

The American Society of Clinical Oncology introduced the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative (QOPI) in 2002 (33). QOPI is an oncologist driven, practice based quality assessment and improvement program (34). Some of the core measures of QOPI address physical and mental symptom management, documentation of whether chemotherapy is given with curative or palliative intent and discussion of that intent with the patient. Importantly, QOPI core measures also include documentation of patient’s advance directive by the third office visit, enrollment in hospice care prior to the last week of life, and decreased rates of systemic chemotherapy administration in the last two weeks of life (34). This initiative is designed to integrate continuous quality improvements into patient-centered clinical practice.

Palliative care and ACP

Growing evidence indicates that ACP is necessary. Patients with advanced cancer benefit from honest prognostic conversations at the time of their initial cancer diagnosis and shared decision-making based on their individual care goals. However, there is less agreement about how it should be delivered. One promising approach is involvement of palliative care providers in ACP. Palliative care is a rapidly expanding field of specialists that, in addition to being trained in aggressive symptom management, are experts in provider-patient communication. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has recognized that optimal oncology care requires the integration of palliative care practices and principles across the trajectory of cancer care.

Given the potential role palliative care can play in ACP, and the evidence indicating the importance of early ACP, studies have started to investigate the role of early implementation of palliative care for patients with advanced cancer. A recent study that has drawn significant attention to the field of palliative care reported on the early initiation of palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. Patients were randomized to receive either early palliative care alongside standard oncologic care or standard oncologic care alone. The patients receiving early palliative care were enrolled within 8 weeks of diagnosis and were seen by a palliative care provider within 3 weeks of study enrollment and then monthly thereafter in the outpatient setting until death. This study demonstrated improvement in both quality of life and mood for patients who received early palliative care. Very significantly, as a secondary outcome, this study also revealed that patients receiving early palliative care underwent less aggressive care at the end-of-life and had an improved overall survival (35). It is possible that at least some of this effect is attributable to palliative care’s contribution to ACP.

Several other efforts to study the effects of improved access to palliative care specialists and principles of care have shown similar benefits. In a nursing led randomized control trial for patients with advanced cancer with a one year estimated survival, patients received either oncologic care with palliative care-focused interventions addressing physical, psychosocial, and care coordination needs, or standard oncologic care alone. Patients in the intervention group received four weekly educational sessions on problem solving, communication and social support, symptom management and ACP. These patients had a significantly higher quality of life and there was a trend toward lower symptom intensity and depressed mood (36).

A study on hospitalized patients, 31% with advanced cancer, demonstrated that those patients randomly assigned to receive interdisciplinary palliative care in addition to standard care, had fewer hospital and intensive care unit admissions and reported greater satisfaction with their care experience and provider communication (37). Another study similarly demonstrated assigning homebound terminally ill outpatients to in-home palliative care, led to greater patient satisfaction, decreased emergency department visits, hospitalization days and an increased likelihood of dying at home (38). In each of these studies the clinical intervention was different, but the common theme was the early introduction of palliative care principles. In addition to aggressive symptom management, palliative care offers patient and family centered communication and care coordination. Though it was not documented in these studies whether patients receiving early palliative care were more likely to discuss ACP, the clinical outcomes of improved quality of life and less aggressive end-of-life care were clearly achieved.

Based largely on these studies, a Provisional Clinical Opinion was published by ASCO stating that, “combined standard oncology care and palliative care should be considered early in the course of illness for any patient with metastatic cancer and/or high symptom burden.” (39). Shortly after this, the Institute of Medicine published a report entitled Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis (40). This clearly acknowledged palliative care as an important component of high-quality cancer care to be initiated at the time of cancer diagnosis.

Conclusions

Patients with advanced cancer are faced with challenging treatment decisions. Their choices are highly influenced by their understanding of the disease course and their prognosis. Oncologists caring for patients are responsible for discussing the available treatment options and the expected disease course. It is also important for oncologists to elicit and document information about individual patient preferences. Unfortunately, these discussions frequently do not occur until patients experience a sudden change in their course or deterioration of their health, prompting providers to address these issues in acute and stressful situations. Delayed ACP discussions frequently result in unwanted care that does not improve or extend a patient’s life. National guidelines suggest that patients should be encouraged to consider ACP early in their disease course, allowing them to carefully consider their own wishes, share their wishes with those that are close to them and discuss death and dying openly and comfortably with their care team. Palliative care specialists are trained in symptom management and provider-patient communication. It has been recognized that optimal oncologic care requires the integration of palliative care early in the course of cancer care. Studies of early introduction of palliative care, have demonstrated improved mood, improved quality of life, fewer emergency department visits, fewer hospital and intensive care unit admissions, greater patient satisfaction and in one study an improved overall survival. Early initiation of palliative care has been shown to achieve many of the desired outcomes of early ACP and therefore may represent the most effective modality of supporting patients through early discussions of their personal treatment preferences.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2014.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network Practice Guidelines in Oncology: NCCN Guidelines for Supportive Care: Palliative Care; 2014.

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care; 2004-2014.

- Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Preparing for the end of life: preferences of patients, families, physicians, and other care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001;22:727-37. [PubMed]

- Haidet P, Hamel MB, Davis RB, et al. Outcomes, preferences for resuscitation, and physician-patient communication among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Am J Med 1998;105:222-9. [PubMed]

- Weeks JC, Cook EF, O’Day SJ, et al. Relationship between cancer patients’ predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA 1998;279:1709-14. [PubMed]

- Pronzato P, Bertelli G, Losardo P, et al. What do advanced cancer patients know of their disease? A report from Italy. Support Care Cancer 1994;2:242-4. [PubMed]

- Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1616-25. [PubMed]

- Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA 2004;291:88-93. [PubMed]

- Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 2000;284:2476-82. [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Definition of Palliative Care; 2013.

- Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300:1665-73. [PubMed]

- Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, et al. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1203-8. [PubMed]

- Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO Jr, et al. Physician factors associated with discussions about end-of-life care. Cancer 2010;116:998-1006. [PubMed]

- Mack JW, Cronin A, Taback N, et al. End-of-life care discussions among patients with advanced cancer: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:204-10. [PubMed]

- Fins JJ, Miller FG, Acres CA, et al. End-of-life decision-making in the hospital: current practice and future prospects. J Pain Symptom Manage 1999;17:6-15. [PubMed]

- Reisfield GM, Wallace SK, Munsell MF, et al. Survival in cancer patients undergoing in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysis. Resuscitation 2006;71:152-60. [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Gallagher ER, et al. Electronic prompt to improve outpatient code status documentation for patients with advanced lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:710-5. [PubMed]

- Stein RA, Sharpe L, Bell ML, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a structured intervention to facilitate end-of-life decision making in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3403-10. [PubMed]

- El-Jawahri A, Podgurski LM, Eichler AF, et al. Use of video to facilitate end-of-life discussions with patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:305-10. [PubMed]

- Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Mitchell SL, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a video decision support tool for cardiopulmonary resuscitation decision making in advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:380-6. [PubMed]

- A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA 1995;274:1591-8. [PubMed]

- Huskamp HA, Keating NL, Malin JL, et al. Discussions with physicians about hospice among patients with metastatic lung cancer. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:954-62. [PubMed]

- Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:315-21. [PubMed]

- Yun YH, Lee CG, Kim SY, et al. The attitudes of cancer patients and their families toward the disclosure of terminal illness. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:307-14. [PubMed]

- Hack TF, Degner LF, Watson P, et al. Do patients benefit from participating in medical decision making? Longitudinal follow-up of women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 2006;15:9-19. [PubMed]

- Delvecchio Good MJ, Good BJ, Schaffer C, et al. American oncology and the discourse on hope. Cult Med Psychiatry 1990;14:59-79. [PubMed]

- American Thoracic Society. Withholding and withdrawing life-sustaining therapy. Ann Intern Med 1991;115:478-85. [PubMed]

- Guidelines for the appropriate use of do-not-resuscitate orders. Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, American Medical Association. JAMA 1991;265:1868-71. [PubMed]

- Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:4387-95. [PubMed]

- Wright AA, Keating NL, Balboni TA, et al. Place of death: correlations with quality of life of patients with cancer and predictors of bereaved caregivers' mental health. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4457-64. [PubMed]

- Quill TE. Perspectives on care at the close of life. Initiating end-of-life discussions with seriously ill patients: addressing the “elephant in the room”. JAMA 2000;284:2502-7. [PubMed]

- McNiff KK, Bonelli KR, Jacobson JO. Quality oncology practice initiative certification program: overview, measure scoring methodology, and site assessment standards. J Oncol Pract 2009;5:270-6. [PubMed]

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. The Quality Oncology Practice Initiative; 2013.

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733-42. [PubMed]

- Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: the Project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741-9. [PubMed]

- Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med 2008;11:180-90. [PubMed]

- Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:993-1000. [PubMed]

- Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:880-7. [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine. Delivering High Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2013.