Acupoint injection treatment for primary osteoporosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

Introduction

Primary osteoporosis (POP) is a metabolic bone disease with clinical characteristics of systemic bone pain, spinal deformity, and increased risk of bone fractures. Senile osteoporosis and postmenopausal osteoporosis are the main components of POP. With the increase in the aging population, the morbidity of osteoporosis is increasing, with an estimated 200 million people affected worldwide (1). In the US, approximately 50% of people aged over 50 years are at risk for osteoporotic fracture (2). More than 60% of osteoporosis patients sustain an associated fracture in their lifetime (3,4), which seriously hinders the treatment of osteoporosis patients and increases the mortality rate (5). Many osteoporosis patients die within 1 year of a hip fracture (6). Therefore, effective strategies to reduce the incidence of fracture are urgently required. In recent years, the problem of osteoporosis has received increasing attention worldwide (7-9).

According to the current practice guidelines, the first-line treatment for POP is anti-osteoporosis medication (10,11), such as bisphosphonates (12), denosumab (13-15), teriparatide (16,17), and salmon calcitonin (18). These drugs are administered orally, intramuscularly or intravenously. In some countries, including China, acupoint injection is often used instead of intramuscular injection to obtain a better curative effect and reduce bad translation (19,20).

Acupoint injection is a supplementary replacement therapy, also known as “water needle”, that involves treating diseases by injecting appropriate medication into relevant acupoints, such as Mingmen (DU 34), Zusanli (ST 36), and Sanyinjiao (SP6). The theory of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) holds that acupoint injection reinforces liver and kidney function and strengthens muscles and bones. At the same time, modern theoretical research also shows that acupoint injection can stimulate the body’s meridian system, generate bioelectric activities, and regulate the functions of the viscera and nervous system, increase the energy state, and strengthen the normal metabolic function of the body (21), Some clinical trials of acupoint injection therapy for POP have been reported; however, a systematic evaluation of the efficacy of acupoint injection therapy for POP remains to be conducted.

High quality meta-analysis is increasingly regarded as a reliable source of research evidence (22-24). Therefore, we conducted this systematic review to evaluate the efficacy and safety of acupoint injection as a clinical treatment for POP.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis were performed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and is presented in accordance with the Preferred Reporting items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (25-28).

Study registration

This protocol used int his systematic review was registered at PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42019130890; http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO).

Search strategy

Seven databases (PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, WanFang Database, and Chinese Biomedical Literature Database) were searched from their inception to March 10, 2019 by two independent authors. The search terms “point injection”, “acupoint injection” and “osteoporosis”, “osteopenia” and the MeSH terms “osteoporosis”, “acupuncture”, acupuncture points” or “injection” were used and RCTs were searched using “random*”; the search strategies were adjusted for each database. Details of the strategies used to search international databases are shown in the supplementary materials.

Selection criteria

The criteria for inclusion in this article were study populations diagnosed as POP that complied with the Reference Standards (results of dual energy X-ray absorptiometry) were scored as standard deviations (SDs) from an average bone mineral density (BMD) in normal young people and reported as T scores. For example, a T score of—2 indicates a BMD that is 2 SDs below the comparative norm. Characteristics such as age, sex, and ethnicity were not restricted. The study design was RCT and interventions were acupoint injection (drug types were not restricted) with conventional intramuscular injection as the control. Explicit reporting of least one of the following outcomes was required: BMD, pain measurement, biochemical markers of bone turnover, adverse effect. Trials were excluded according to the following criteria: (I) different drugs used in the intervention and control groups; (II) incomplete data that could not be analyzed; (III) unreasonable diagnostic method and standard; (IV) review studies, editorials, case reports, and letters; (V) duplicate publications.

Data extraction

Data were extracted by two authors independently. All differences were settled by discussion between the two researchers. If no agreement was reached, a third reviewer was consulted. Data extracted included the basic information of the trial (name of the first author, year of publication), basic research information (patient information, experimental intervention, control intervention), evaluation time, outcomes (BMD, pain measurement, fracture incidence, etc.) and relevant important variables. If information was missing, we contacted the authors of the primary studies.

Quality assessment

Two authors independently evaluated risk of bias in the included RCTs using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool (29). This tool assesses the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other sources of bias. We rated each domain as low, unclear, or high risk of bias. We classified the overall risk of bias as low if all domains were at low risk of bias, as high if at least one domain was at high risk of bias, or as unclear if at least one domain was at unclear risk of bias and no domain was at high risk. This rule is specified by Cochrane’s tool for assessing risk of bias in RCTs, because any source of bias in a trial is problematic and there is a paucity of empirical research that supports prioritization of one domain over the others (26).

Statistical analysis

The outcomes were BMD, pain measurement, and biochemical markers of bone turnover. Meta-analysis was performed using Review Manager Software 5.3. Dichotomous variables were calculated as relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI), and continuous variables were calculated as the mean difference (MD) and standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI (30). The degree of heterogeneity (I2) of each outcome was analyzed using the Chi-square test, with no significance designated by P>0.05 (31). I2<50% indicated low heterogeneity of the data and the fixed effect model adopted for a meta-analysis; otherwise the random effects model was used. If substantial heterogeneity was detected, subgroup or sensitivity analysis was applied to explore the causes of heterogeneity. If the sources of heterogeneity could not be determined, we adopted descriptive analysis.

Results

Literature search

We found a total of 1,416 relevant articles in the initial searches of the relevant databases; 779 remained after removing the duplicates. A total of 762 studies were excluded based on abstract/title screening. Twelve additional articles were removed because three were duplicates of studies already included and nine included inappropriate interventions or comparisons. Finally, five trials were included in this systematic review (19,20,32-34) (Figure 1).

Characteristics of the included trials

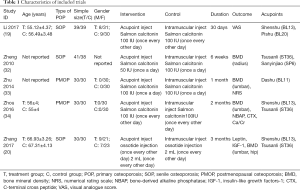

The five studies included 337 participants (170 cases in the treatment group and 167 cases in the control group). All the studies were from single centers, and the largest sample size was less than 80 cases. The average age of patients within the groups was >50 years. Types of POP were senile osteoporosis (19,20,32) (3 trials) and postmenopausal osteoporosis (33,34) (2 trials).

Medication for acupoint injection in studies consisted of salmon calcitonin (19,32-34) (4 trials) and ossotide injection (20) (1 trial). The frequency of acupoint injection was once every other day (19,20,34) (3 trials) and once a day (32,33) (2 trials). The treatment duration ranged from 1 month to 3 months. Adverse effects were not reported in any of the trials. For acupuncture points selection, three trials adopted Tsusanli (ST36) (20,32,34) for injection, two trials used Shenshu (BL13) (19,34), while Dashu (BL11) (33), PiShu (BL20) (19) and Sanyinjiao (SP6) (32) were chosen as acupuncture points in one trial each (Table 1).

Full table

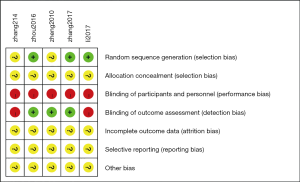

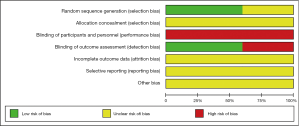

Risk of bias

Details of the methodological quality of the included studies are presented in Figures 2,3. Three articles were rated as high risk because of the imperfect implementation of blind methods for researchers and patients. Two articles were rated as high risk because of inadequate blind methods for researchers, patients and outcomes. Therefore, all trials were judged as high risk because one or more aspects of the bias assessments were labeled high.

Meta-analysis

BMD

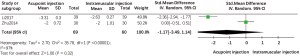

All of the enrolled trials reported BMD. Among them, three trials reported lumbar BMD, one trial reported left distal one-third radial BMD and hip BMD. The merged data indicated the existence of significant differences between acupoint injection therapy and intramuscular injection therapy in improving BMD (MD =0.02; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.03, P<0.00001) (Figure 4). Subgroup analysis of three studies indicated that acupoint injection had some advantages over intramuscular injection in increasing lumbar BMD (MD =0.02; 95% CI, 0.01 to 0.03, P<0.00001). Subgroup analysis showed that acupoint injection of salmon calcitonin significantly increased distal one-third radial BMD compared with the effects of intramuscular injection (MD =0.01; 95% CI, 0.00 to 0.03, P<0.05). Additional subgroup analysis showed that acupoint injection of ossotide significantly couldn’t improve hip BMD significantly compared with the effects of intramuscular injection (MD =0.02; 95% CI, −0.01 to 0.05, P>0.05).

Pain measurement

One trial reported the use of the numerical rating scale (NRS) to measure pain (33), whereas another trial reported the use of the visual analogue score (VAS) (19); therefore, we merged the data using a random effects model. Compared with intramuscular injection of salmon calcitonin, our analysis indicated that acupoint injection of this agent did not provide a significant advantage in pain reduction (SMD =−1.17; 95% CI, −3.49 to 1.14, P>0.05). Heterogeneity between the two groups was high due to differences in scoring criteria and duration of treatment (Figure 5).

Biochemical indicators

Biochemical markers such as such as NBAP, CTX, Ca/Cr, leptin and IGF-1 were analyzed to compare the effects of acupoint injection and intramuscular injection for the treatment of POP. In one trial, acupoint injection of salmon calcitonin reduced levels of CTX (MD =−44.10; 95% CI, −62.45 to −25.75, P<0.05) and NBAP (MD =5.20; 95% CI, 4.59 to 5.81, P<0.05) and reduced urine Ca/Cr levels (MD =−0.05; 95% CI, −0.12 to 0.02, P>0.05). In another trial, acupoint injection showed a significantly greater improvement in IGF-I levels (MD =13.51; 95% CI, 6.54 to 20.48 P<0.05), while leptin levels were reduced (MD =−1.37; 95% CI, −2.26 to −0.48, P<0.05).

Publication bias

Publication bias was not evaluated due to the limited availability of relevant literature.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

In this systematic review, we included five RCTs with 337 osteoporosis patients. Our evaluation suggests that acupoint injection therapy offers some benefits to POP patients. Acupoint injection increased lumbar and distal one-third radial BMD and enhanced the levels of biological indicators including NBAP, and IGF-I level, while decreasing CTX and leptin levels. However, acupoint injection appeared to offer no significant advantage over intramuscular injection for improving hip BMD, level of urine Ca/Cr and the relief of pain caused by osteoporosis. CTX is used mainly as a marker of bone resorption in metabolic osteopathy, although it is a more sensitive indicator of bone resorption due to estrogen deficiency (35). The level of BMD can reflect the risk of fracture in osteoporosis patients (36). IGF-1 promotes bone matrix synthesis, inhibits bone metabolism, prevents calcium loss, and maintains the normal structure and function of bone (37). Analysis of these markers suggested that acupoint injection is more effective than intramuscular injection for the treatment of POP.

However, these effects may be related to the selection of acupoints and meridians. Our systematic review suggested variation in the effects of five different acupoints used for injection, which belonged to three meridians (stomach, bladder and spleen) according to the principle of the acupoint selection in the theory of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). According to this theory, Tsusanli (ST36) regulates the spleen and stomach, nourishing qi and supplementing blood, Shenshu (BL23) supplements the kidney essence, and Dazhu (BL11) strengthens the sinews and bones and passes the channels and collaterals. PiShu (BL20) has the effect of invigorating the spleen and qi. Sanyinjiao (SP6) is an acupoint that crosses the meridians of the liver, spleen and kidney to regulate the functions of these organs. TCM describes osteoporosis as “bone impotence” (35), with the main etiology and pathogenesis being liver and kidney deficiency, supplemented by spleen deficiency. Injecting at those acupuncture points could nourishing the spleen and reinforce the kidney, thus benefiting osteoporosis patients. Animal studies also showed that stimulation of Tsusanli (ST36), Shenshu (BL23) and PiShu (BL20) acupoints regulated the effect of sex hormones, improve bone metabolism and quality and prevented bone loss (38-40). One research suggested that inject salmon calcitonin in acupuncture point could better improve BMD and clinical symptoms compared with injecting saline. The potential mechanism may be acupoint injection produces lasting stimulation to acupoints and exerts the efficacy of acupoints. on the other hand, it exerts anti-osteoclast effect by using salmon calcitonin itself (34). The mechanism of acupoint injection might have better drug transfer mechanism than regular intramuscular injection maybe related to the characteristic distribution of nerve innervation and the vascular effects in different parts of the central nervous loop, which can led to neurogenic inflammation of visceral tissue (41).

Implications for the future research

Further studies in different population groups are required to more fully clarify the therapeutic efficacy of acupoint injection on POP. All previous studies on acupoint injection for POP were conducted in China and all participants were mongoloid. Few studies have been reported in Western countries, possibly because acupoint injection technology is a branch of acupuncture, it need to inject medicine in the acupuncture point. Acupuncture point is based on TCM theory. Maybe it is not widely used in these regions. A systematic review and meta-analysis had been conducted by Taru. In his systematic review most participants were westerners. The result showed that acupuncture could significantly reduce the pain intensity in patients with osteoarthritis. The pain of arthritis or osteoporosis belongs to bone pain. Therefore, it may be speculated that acupoint injection, which is an extension of acupuncture therapy will be equally effective in reducing pain intensity in western populations (42).

Future studies require improvements in methodological quality of and increased numbers of patients. Since the number of existing studies is relatively small, future studies may have an impact on our understanding of the effectiveness of acupoint injection therapy for osteoporosis patients based on existing research. Clinical trial registration and sample size calculation were not available for any of the five trials evaluated here. Furthermore, fracture incidence, which is the endpoint outcome of POP, was not reported in any of the trials. Future studies on acupoint injection for POP should be conducted with strict methodology including long-term follow-up and reported to comply with the relevant guidelines (43,44).

As a new supplementary and replacement therapy, the safety of acupoint injection requires clarification. While none of the included trials reported adverse effect. In searches of other trials of acupoint injection therapy for POP, we found reports of chest tightness, palpitation, sweating and nausea during the therapy. Symptoms of discomfort were mild, with rapid recovery after treatment (45,46). Other research about acupoint injection therapy suggest that even though local pain main be occurs in some patients, while they were not serious, the adverse effect and rate were no significant differences from other therapies (47).

Superiority and limitations

This is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of acupoint injection therapy for POP in comparison with other treatments. This article also focused on the safety of acupoint injection, but unfortunately, no included studies reported indicators of safety, thus preventing us from reaching a conclusion about the safety of acupoint injection for POP.

There are several limitations to this review. First, the trials we searched were Chinese and English published. While we tried our best to retrieve five international databases, representativeness of these included articles may not be affected. Second, the heterogeneity of data after merging statistics was high, possibly due to sources such as the differences in the sex ratio of the patients in each study, acupuncture points for injection, treatment frequency and duration of treatment. Third, our analysis was based only on current research and future research may have an impact on the current results. These limitations, and the shortcomings in methodology, prevent us from making a definitive conclusion; therefore, we plan to update this systematic review after 2 years.

Conclusions

Compared with intramuscular injection, our findings suggest that acupoint injection therapy provides advantages in terms of improvements in BMD and some biochemical indicators in patients with POP. However, this effect also depends on the selection of acupoints for injection. At present, the adverse effects of acupoint injection have received little attention and there are shortcomings in the methodology of the existing RCTs. Future studies should follow the relevant guidelines and improve the quality of the methodology. The treatment frequency, acupuncture point selection and fracture incidence associated with acupoint injection for POP should also be investigated.

Supplementary

Search Strategies for Pubmed, Embase, Web of Scienece and Cochrane Library

PubMed

#1 osteoporosis[tiab] OR osteopenia[tiab]

#2 piont injection[tiab] OR acupoint injection[tiab]

#3 osteoporosis[mesh]

#4 Acupuncture[mesh] OR Acupuncture Points[mesh] OR Injection[mesh]

#5 ((“Clinical Trials, Phase II as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Clinical Trials, Phase III as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Clinical Trials, Phase IV as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Controlled Clinical Trials as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Intention to Treat Analysis”[Mesh] OR “Pragmatic Clinical Trials as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Clinical Trials, Phase II”[Publication Type] OR “Clinical Trials, Phase III”[Publication Type] OR “Clinical Trials, Phase IV”[Publication Type] OR “Controlled Clinical Trials”[Publication Type] OR “Randomized Controlled Trials”[Publication Type] OR “Pragmatic Clinical Trials as Topic”[Publication Type] OR “Single-Blind Method”[Mesh] OR “Double-Blind Method”[Mesh])) OR (random*[Title/Abstract] OR blind*[Title/Abstract] OR singleblind*[Title/Abstract] OR doubleblind*[Title/Abstract] OR trebleblind* [Title/Abstract] OR tripleblind*[Title/Abstract])

#6 #1 or #3

#7 #2 or #4

#8 #5 and #6 and #7

Embase

#1 osteoporosis:ab,ti OR osteopenia:ab,ti

#2 piont injection:ab,ti OR acupoint injection:ab,ti

#3 osteoporosis'/exp

#4 Acupuncture'/exp OR Acupuncture Point'/exp OR Injection'/exp

#5 'multicenter study (topic)'/exp OR 'phase 2 clinical trial (topic)'/exp OR 'phase 3 clinical trial (topic)'/exp OR 'phase 4 clinical trial (topic)'/exp OR 'controlled clinical trial (topic)'/exp OR 'randomized controlled trial (topic)'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp

#6 random*:ab,ti OR blind*:ab,ti OR singleblind*:ab,ti OR doubleblind*:ab,ti OR trebleblind*:ab,ti OR tripleblind*:ab,ti

#7 #1 OR #3

#8 #2 OR #4

#9 #5 OR #6

#10 #7 AND #8 AND #9

Web of Science

#1 osteoporosis:ti OR osteopenia:ti

#2 piont injection:ti OR acupoint injection:ti

#3 #1 AND #2

Cochrane Library

#1 (osteoporosis):ti,ab,kw OR (osteopenia):ti,ab,kw

#2 (piont injection):ti,ab,kw OR (acupoint injection):ti,ab,kw

#3 MeSH descriptor:[Osteoporosis] explode all trees

#4 MeSH descriptor:[Acupuncture] explode all trees

#5 MeSH descriptor:[Acupuncture Point] explode all trees

#6 MeSH descriptor:[Injection] explode all trees

#7 #1 OR #3

#8 #2 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6

#9 #7 AND #8

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, China Program (No. 81860864), and it was funded by Laboratory of Intelligent Medical Engineering of Gansu Province (Grant no. GSXZYZH2018001), and it was also funded by the Special Scientific Research Project for Business Construction of Clinical Research Base of Traditional Chinese Medicine of State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (JDZX2015080).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This is a systematic review and meta-analyses, the study didn’t use any private patients’ data.

References

- Kanis JA, on behalf of the World Health Organization Scientific Group. Assessment of osteoporosis at the primary health-care level. Technical Report. University of Sheffield, UK: World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Diseases. University of Sheffield; 2007.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, 2004.

- Pan H, Jin R, Li M, et al. The Effectiveness of Acupuncture for Osteoporosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Chin Med 2018;46:489-513. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jang EJ, Lee YK, Choi HJ, et al. Osteoporotic Fracture Risk Assessment Using Bone Mineral Density in Korean: A Community-based Cohort Study. J Bone Metab 2016;23:34-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:2359-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- D’Amelio P, Isaia GC. Male Osteoporosis in the Elderly. Int J Endocrinol 2015;2015:907689.

- Gehlbach S, Hooven FH, Wyman A, et al. Patterns of anti-osteoporosis medication use among women at high risk of fracture: findings from the Global Longitudinal Study of Osteoporosis in Women (GLOW). PLoS One 2013;8:e82840. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McLeod KM, Johnson S, Charturvedi R, et al. Bone mineral density screening and its accordance with Canadian clinical practice guidelines from 2000–2013: an unchanging landscape in Saskatchewan, Canada. Arch Osteoporos 2015;10:227. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barnard K, Lakey WC, Batch BC, et al. Recent Clinical Trials in Osteoporosis: A Firm Foundation or Falling Short? PLoS One 2016;11:e0156068. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan SN, Craig L, Wild R. Osteoporosis: therapeutic guidelines. Guidelines for practice management of osteoporosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2013;56:694-702. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Compston J, Bowring C, Cooper A, et al. Diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women and older men in the UK: National Osteoporosis Guideline Group (NOGG) update 2013. Maturitas 2013;75:392-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jansen JP, Bergman GJ, Huels J, et al. Prevention of vertebral fractures in osteoporosis: mixed treatment comparison of bisphosphonate therapies. Curr Med Res Opin 2009;25:1861-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bone HG, Bolognese MA, Yuen CK, et al. Effects of denosumab on bone mineral density and bone turnover in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93:2149-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, et al. freedom Trial. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2009;361:756-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Papapoulos S, Lippuner K, Roux C, et al. The effect of 8 or 5 years of denosumab treatmentin postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: results from the freedom extension study. Osteoporos Int 2015;26:2773-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cosman F, Lindsay R. Therapeutic potential of parathyroid hormone. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2004;2:5-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1-34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1434-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dimai HP, Pietschmann P, Resch H, et al. Austrian guidance for the pharmacological treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women--update 2009. Wien Med Wochenschr Suppl 2009;122:1-34. [PubMed]

- Li PN, Xu D. Effect Analysis of Point Injection with Salmon Calcitonin Combined with Nursing Intervention in Treating Pain Due to Osteoporosis. J New Chin Med 2017;7:139-41.

- Zhang HC. Acupoint injection of ossotide injection Clinical Observation on 30 Cases of Senile Osteoporosis. Hunan J of TCM 2017;33:84-6.

- Krause MS, Nakajima ST. Hormonal and nonhormonal treatment of vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2015;42:163-79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tian J, Zhang J, Ge L, et al. The methodological and reporting quality of systematic reviews from China and the USA are similar. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;85:50-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yao L, Sun R, Chen YL, et al. The quality of evidence in Chinese meta-analyses needs to be improved. J Clin Epidemiol 2016;74:73-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiu-xia L, Zheng Y, Chen YL, et al. The reporting characteristics and methodological quality of Cochrane reviews about health policy research. Health Policy 2015;119:503-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higgins J, Green SE. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0.

- Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yan P, Yao L, Li H, et al. The methodological quality of robotic surgical meta-analyses needed to be improved: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol 2019;109:20-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ge L, Tian JH, Li YN, et al. Association between prospective registration and overall reporting and Methodological quality of systematic reviews: a meta-epidemiological study. J Clin Epidemiol 2018;93:45-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ioannidis JP, Patsopoulos NA, Evangelou E. Heterogeneity in meta-analyses of genome-wide association investigations. PLoS One 2007;2:e841. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zheng ZH, Ren ZH. Clinical study on point-injection of salmon calcitonin treatment of senile osteoporosis. Chin J Osteoporos 2010;16:515-7.

- Zhu R, Wu YC. Observations on the Therapeutic Effect of Single Acupuncture Point Injection on Postmenopausal Osteoporosis. Shanghai J Acu-mox 2014;33:337-8.

- Zhou Z, Wang N, Ding C, et al. Postmenopausal osteoporosis treated with acupoint injection of salmon calcitonin: a randomized controlled trial. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2016;36:705-8. [PubMed]

- Tian YM, Li R, Jia QQ, et al. Current advances in the treatment of osteoporosis with acupuncture and acupuncture combined with traditional Chinese medicine. Chin J Osteoporos 2019;25:263-7.

- Silva DMW, Borba VAZ, Kanis JA. Evaluation of clinical risk factors for osteoporosis and applicability of the FRAX tool in Joinville City, Southern Brazil. Arch Osteoporos 2017;12:111. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosen CJ. Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factors, and the senes-cent skeleton: Ponce de Leon’s fountation revisited? J Cell Biochem 1994;56:348. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang L, Liu YY, Lu T, et al. Effects of Warm Acup-Moxibustion at Shenshu Point on Sexual Hormones in Senile Female Rats. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2001;21:172-3.

- Zhao YX, Yan ZG, Shao SJ, et al. Effect of Acupuncture and Moxibustion on Experimental Osteoporosis. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 1999;5:301-3.

- Zhao YX, Yan ZG, Yu AS, et al. The Influence of Acupuncture and Moxibustion on Bony Metabolism of Rats After Ovariectomy. Shanghai J Acu-mox 1999;18:40-1.

- Cao DY, Niu HZ, Zhao Y, et al. Neurogenic Inflammation of the Visceral Organs Evoked by Electrical Stimulation of Acupoint in Rats. Chinese Acupuncture & Moxibustion 2001;11:662-4.

- Manyanga T, Froese M, Zarychanski R, et al. Pain management with acupuncture in osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:312. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang K, Chen YL, Li YP, et al. Editorial: can China master the guideline challenge? Health Res Policy Syst 2013;11:1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Benzvi L, Gershon A, Lavi I, et al. Secondary prevention of osteoporosis following fragility fractures of the distal radius in a large health maintenance organization. Arch Osteoporos 2016;11:20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liang XH, Su RB. Therapeutic effect of acupoint injection combined with alendronate sodium in the treatment of low back pain in osteoporosis. J Wenzhou Medical University 2016;46:539-42.

- Zou XJ, Hao YY, Zhou JT, et al. Curative Effect Observation on Point Injection of Saline Combined with Routine Western Medicine for Primary Senile Osteoporosis. J New Chin Med 2018;50:183-5.

- Wang LQ, Chen Z, Zhang K, et al. Zusanli (ST36) Acupoint Injection for Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Altern Complement Med 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]