Assessing the palliative care needs and service use of diverse older adults in an urban medically-underserved community

Introduction

Although palliative care (PC) has become increasingly prevalent over the past several decades (1,2), significant gaps persist in access to and utilization of services. Home and community-based hospice programs serving people who are terminally ill have proliferated since the early 1980s, but PC programs for people living with chronic or serious illnesses remain primarily hospital-based, with limited reach into community settings (3,4). The lack of palliative and supportive care services to meet the needs of seriously-ill older adults living in the community perpetuates critical health care disparities in this growing population.

PC has been particularly underutilized by African American and Latino older adults and those who live in low-income, medically-underserved areas (5-10). Research on disparities affecting diverse populations reveals the interaction of multiple barriers, including lack of familiarity with PC, inadequate access to care, financial hardship, and social barriers such as mistrust and communication impediments between providers and patients (5,8,11). Living in low income, urban communities may present additional obstacles, including the costs of transportation and availability of pain medications in urban pharmacies (9,10,12,13). Kayser and colleagues (14) explored barriers to PC in five low-income urban communities and found that minority stress, feelings of disempowerment, and lack of community supports posed further barriers to accessing palliative services. Despite growing evidence of inequities in use of PC, however, the perspectives of diverse, chronically-ill older adults living in the community have largely been absent from the literature.

This article describes the findings of an exploratory, mixed-method community needs assessment of seriously-ill older adults who live in New York City’s East and Central Harlem neighborhoods. The investigators explored the prevalence of chronic conditions and associated symptoms among diverse community-dwelling older adults, the individual and community resources older residents employ to manage and ameliorate these symptoms, and the barriers they face in accessing PC and pain management in the community.

East and Central Harlem in New York City are Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)-designated medically underserved areas in northern Manhattan with diverse aging populations, high rates of poverty and lack of health insurance, and a shortage of primary care physicians (15,16). Despite the proximity of several large health systems and community-based health initiatives (17), the mostly Latino and African American older adults living in these communities are more likely to live with multiple chronic conditions and report poorer access to care than their age-peers throughout the city (15,16).

Methods

The study emerged from an academic-community partnership exploring the PC needs of older community residents that brought together researchers from a public university, an academic medical center, community members, and multidisciplinary service providers from over 40 community-based aging-services and faith-based organizations. We utilized a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach that has been shown to enhance community engagement and capacity-building in research on health and health disparities (18,19). CBPR entails active inclusion of community partners through all phases of the research, including study design, sampling, data collection, analysis, and dissemination of findings. Following exploratory meetings with key community informants (including older residents, service providers, clergy and other faith leaders), we formed a community council of older residents and professionals that met regularly throughout the project to review and guide the needs assessment, explore the unmet needs of seriously ill older community members, interpret findings, and strategize next steps.

We began by conducting semi-structured qualitative interviews with a purposive sample of service providers and leaders from community-based aging services programs. After stratifying programs by type of organization (i.e., senior centers, case management agencies, senior housing programs, and churches and other houses of worship) and catchment area, we interviewed providers about the needs of the older adults they serve, community supports, service barriers, and perceptions of PC. We followed these key-informant interviews with snowball sampling to recruit community-dwelling older adults (60+ years old) living with at least one chronic illness in East and Central Harlem through provider and participant referrals, study flyers, and announcements at community boards and other neighborhood meetings.

The older adult interviews incorporated questions from the Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (20), the Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Study (21), and questions from prior research on urban community-dwelling, low-income, minority older adults about service needs, chronic illness self-management, coping, access to supports and services, and socio-demographics (22). Interviews were conducted in Spanish and English, and took place primarily in-person at community-based organizations. Eligible older adult participants were ≥60 years of age with a self-reported diagnosis of at least one chronic condition. Mean interview length was 29 minutes and participants were provided $20 for their participation. The study protocol was approved by the CUNY Institutional Review Board (IRB #: 421773-4), and all participants gave informed consent prior to participation. Quantitative data were entered into Qualtrics software (Provo, UT; 2017) and downloaded directly into SPSS, v. 20 (Armonk, NY; 2013) to facilitate analysis of descriptive statistics and selected bivariate associations of client demographic characteristics, unmet needs, and use of formal and informal services. Qualitative data were analyzed by an interdisciplinary team that employed systematic grounded theory coding and analysis elaborated by Corbin & Strauss (23).

Results

Provider interviews

We interviewed 41 aging-services providers from 33 community-based social and faith-based organizations in East (n=19) and Central Harlem (n=14), including churches (n=12), senior centers (n=9), case management organizations (n=8), social service agencies (n=6), senior housing developments (n=4), and pharmacies (n=2). Systematic, iterative coding and analysis of verbatim transcripts from audiotaped interviews yielded several themes. Providers across organizations and catchment areas told us that managing chronic conditions and burdensome symptoms presented significant challenges for many of the older adults they served. Many (67%) providers reported that helping clients manage their health and promoting physical wellbeing was part of the mission of their organizations, but few (10%) were aware of medical services available in their community, such as PC or pain management, that directly address these concerns. After interviewers read providers a definition of PC drawn from the National Consensus Project (24), a majority (78%) agreed that many of their clients could benefit from PC. Most of the providers (84%) told us their organizations offered some services that supported older adults living with chronic illnesses and conditions, most commonly emotional or spiritual support via counseling or support groups (79%), concrete assistance or case management such as arranging transportation or providing financial resources (71%), and assistance with healthcare decision-making and legal/financial planning (46%).

Providers described multiple barriers that might prevent older community members from using formal medical services such as PC. Providers reported their older clients lacked access to services due to mobility limitations (52%), difficulties with transportation (63%) and financial insecurity (44%). Several providers (17%) felt older adults might be reluctant to discuss their burdensome symptoms or unmet needs with providers due to cultural and language barriers.

Older adult interviews

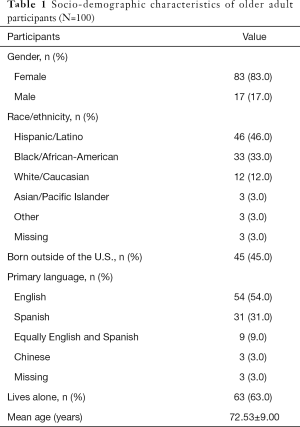

We interviewed 100 community-dwelling older adults in East and Central Harlem. As reported in Table 1, participants had a mean age of 72.5 years, a majority (63.0%) lived alone, and most (83%) were female. Almost half (46.0%) of participants identified themselves as Hispanic/Latino and 33.0% Black/African American, reflecting the demographics of the community. Approximately 45.0% reported they were born outside of the continental U.S., with over a quarter of the sample (26.0%) from Puerto Rico, 6% from the Dominican Republic, 6.0% from South and Central America, 3.0% from Mexico, 3.0% from China, and 2.0% from Europe. Almost a third (31.0%) of our sample identified Spanish as their primary language, and one quarter (25.0%) chose to complete interviews in Spanish.

Full table

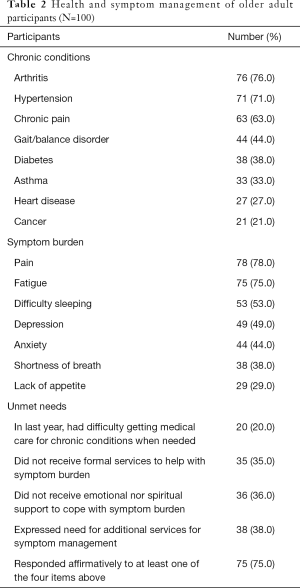

Chronic illness and symptom burden

Most participants reported they live with one or more chronic conditions, primarily arthritis (76.0%), hypertension (71.0%), and chronic pain (63.0%). A majority indicated they had experienced illness-related symptoms in the two weeks prior to the interviews, most frequently pain (78.0%), fatigue (75.0%), and sleeping difficulties (53.0%), which participants rated as their most burdensome symptoms. Almost half of the participants experienced depression (49.0%) or anxiety (44.0%) related to their chronic conditions (see Table 2). Over half of participants (54.0%) reported they experienced challenging symptoms most of, if not all the time, and 39.0% rated their symptoms as severe or very severe.

Full table

Symptom management and care needs

Over a third (35.0%) of the older adults reported they did not use medical services to help manage their burdensome symptoms, and 36.0% received no instrumental, emotional, or spiritual support around their illness (see Table 2). Of those participants who did receive assistance, nearly half (48.0%) reported that help came from family and friends, approximately a third (32.0%) from physicians or other medical providers, and the remainder (20.0%) from home health aides or care attendants. Almost half (46.0%) indicated they received emotional and spiritual support from their churches or prayer/faith fellowships.

Perceptions of and barriers to PC

Consistent with provider reports, a majority of the older adults (88%) reported they had never heard of PC and were unsure of what palliative services entailed. Most participants (93%) told interviewers they had never discussed PC with a health care provider. One in five participants (20%) reported they had experienced difficulties in accessing medical services, and 38% expressed a need for additional assistance in managing their burdensome symptoms. Over a quarter (26%) of participants reported concerns about the financial costs of treatment or medications, and almost half (47%) had experienced difficulty paying medical or pharmacy bills. Almost two-thirds (64%) of those who had not received PC indicated they would be interested in learning more about PC, and many (72%) reported they would be comfortable receiving services around their illness-related symptoms at the community-based organizations where we interviewed them.

Discussion

Although consistent with past research on low-income, diverse communities (25,26), the high prevalence of symptom burden and unmet needs in our sample of chronically-ill older adults living in East and Central Harlem was alarming. Multiple morbidities and high symptom burden in later life are often associated with poor quality-of-life, increased hospitalizations, emergency room visits, and nursing home placements (27,28). Despite the existence of several large medical centers and health systems in and adjacent to East and Central Harlem, most of the older adults we surveyed did not take advantage of PC and pain management services, a medical specialty that has been shown to improve health and social outcomes for seriously ill patients and their caregivers (29-31). The older participants draw on informal support from family and friends, churches, and community services to help them manage their burdensome symptoms day-to-day. However, many live with chronic untreated pain, fatigue, depression and other symptoms associated with their medical conditions.

The older adults and aging-services providers we surveyed described multiple barriers to accessing medical and supportive services that can reduce symptom burden and psychosocial-spiritual distress. Providers and community-dwelling older adults were largely unfamiliar with PC and pain management, and most reported unmet needs around pain and other symptoms with their providers. Both groups spoke of financial concerns, cultural and language barriers. These barriers are consistent with extant research on PC disparities in diverse, urban communities (9,10,12-14).

Several limitations must be considered regarding our findings. A purposive sampling strategy helped us reach a population that is often difficult to access in health services research, but limits our ability to generalize findings outside of this geographic and service area. A disproportionate number of women were interviewed, and recruiting participants from community-based settings provided an opportunity to document the experiences of older adults who use such services regularly, but not necessarily those who are unable to do so such as homebound or homeless elders. Further, we did not test our measures for reliability and validity. Nonetheless, the study contributes to an emerging literature on the burdens and challenges facing diverse, community-dwelling older Americans who live, often for months or years, with multiple chronic illnesses and conditions.

In summary, findings from this exploratory study highlight the high symptom burden and unmet needs of Black and Latino older adults living in underserved communities with serious illness. These findings contribute to a growing literature on disparities in PC (5,6,8,10,13), calls for increased education about PC (4,11,14), and the need for further development of community-based programs tailored to the needs of seriously ill older residents of low-income, racially/ethnically diverse communities (3,4,14,32-35). In addition, the investigators’ successful engagement with service and faith-based providers and older residents in East and Central Harlem confirms the benefits of developing community partnerships and using CBPR methods to engage diverse stakeholders in addressing the challenges older adults and their families face in managing serious illnesses (18). Lastly, the study demonstrates the opportunities inherent in partnering with community members, community-based organizations, and churches to better understand and ultimately reduce health disparities in later life.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially supported by a grant from the Fan Fox & Leslie R. Samuels Foundation.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- Dumanovsky T, Augustin R, Rogers M, et al. The growth of palliative care in US hospitals: a status report. J Palliat Med 2016;19:8-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morrison RS, Maroney-Galin C, Kralovec PD, et al. The growth of palliative care programs in United States hospitals. J Palliat Med 2005;8:1127-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kamal AH, Currow DC, Ritchie CS, et al. Community-based palliative care: the natural evolution for palliative care delivery in the US. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013;46:254-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reid MC, Ghesquiere A, Kenien C, et al. Expanding palliative care's reach in the community via the elder service agency network. Ann Palliat Med 2017;6 Suppl 1:S104-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crawley L, Payne R, Bolden J, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care in the African American community. JAMA 2000;284:2518-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Johnson KS. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1329-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Gibby CC, Anderson KO, Shete S, et al. Early referral to supportive care specialists for symptom burden in lung cancer patients: a comparison of non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic blacks. Cancer 2012;118:856-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gardner DS, Doherty M, Bates G, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in palliative care: A systematic scoping review. Fam Soc 2018;99:301-16. [Crossref]

- Hughes A. Poverty and palliative care in the US: issues facing the urban poor. Int J Palliat Nurs 2005;11:6-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Born W, Greiner KA, Sylvia E, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about end-of-life care among inner-city African Americans and Latinos. J Palliat Med 2004;7:247-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dobrof J, Heyman JC, Greenberg RM. Building on community assets to improve palliative and end-of-life care. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2011;7:5-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morrison RS, Wallenstein S, Natale DK, et al. “We don't carry that”: failure of pharmacies in predominantly nonwhite neighborhoods to stock opioid analgesics. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1023-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker T, et al. The unequal burden of pain: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med 2003;4:277-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kayser K, DeMarco RF, Stokes C, et al. Delivering palliative care to patients and caregivers in inner-city communities: challenges and opportunities. Palliat Support Care 2014;12:369-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- King L, Hinterland K, Dragan KL, et al. Community health profiles 2015. Manhattan Community District 11: East Harlem 2015. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

- King L, Hinterland, K, Dragan KL, et al. Community Health Profiles 2015, Manhattan Community District 10: Central Harlem 2015. The New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

- Payne R, Payne TR, Heller KS. The Harlem Palliative Care Network. J Palliat Med 2002;5:781-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Riffin C, Kenien C, Ghesquiere A, et al. Community-based participatory research: Understanding a promising approach to addressing knowledge gaps in palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2016;5:218-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract 2006;7:312-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, et al. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 1991;7:6-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lorig K, Stewart A, Ritter P. Stanford chronic disease self-management study. In: Lorig K, Stewart A, Ritter P, et al. editors. Outcome measures for health education and other health care interventions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996:24-5.

- Friedman D, Parikh NS, Giunta N, et al. The influence of neighborhood factors on the quality of life of older adults attending New York City senior centers: results from the Health Indicators Project. Qual Life Res 2012;21:123-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corbin J, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research. 4th ed. New York: Sage; 2014;456.

- Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, et al. The national agenda for quality palliative care: the National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007;33:737-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walke LM, Gallo WT, Tinetti ME, et al. The burden of symptoms among community-dwelling older persons with advanced chronic disease. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:2321-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eckerblad J, Theander K, Ekdahl A, et al. Symptom burden in community-dwelling older people with multimorbidity: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 2015;15:1-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cleeland CS. Symptom burden: multiple symptoms and their impact as patient-reported outcomes. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2007.16-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salanitro AH, Hovater M, Hearld KR, et al. Symptom burden predicts hospitalization independent of comorbidity in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:1632-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McDonald J, Swami N, Hannon B, et al. Impact of early palliative care on caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: cluster randomized trial. Ann Oncol 2017;28:163-168. [PubMed]

- Casarett D, Pickard A, Bailey FA, et al. Do palliative consultations improve patient outcomes? J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:593-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, et al. The comprehensive care team: a controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:83-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hall S, Petkova H, Tsouros A, et al. Palliative care for older people. Copenhagen, Denmark: World Health Organization 2011;72.

- Cassel JB, Kerr KM, Kalman NS, et al. The business case for palliative care: translating research into program development in the US. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:741-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rabow M, Kvale E, Barbour L, et al. Moving upstream: a review of the evidence of the impact of outpatient palliative care. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1540-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ceronsky L, Shearer J, Weng K, et al. Minnesota Rural Palliative Care Initiative: building palliative care capacity in rural Minnesota. J Palliat Med 2013;16:310-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]