The experiences of suffering of end-stage renal failure patients in Malaysia: a thematic analysis

Introduction

The prevalence of end-stage renal failure (ESRF) has been increasing over the past two decades (1). ESRF is a chronic debilitating disease with significant associated morbidity and mortality. Renal replacement therapy (RRT) is costly, and places an enormous burden on national healthcare systems as well as the global economy. In Malaysia, the dialysis prevalence rate increased from 440 per million population (pmp) in 2004 to 1,235 pmp in 2013. This increase in prevalence was largely contributed by the growing numbers of patients with diabetic kidney disease, accounting for 61% of new patients accepted for dialysis (2).

The majority of ESRF patients continue to experience suffering despite receiving dialysis treatment. Their quality of life was compromised and they experienced varying restrictions in their activities of daily living (3-6). In addition, many suffered because their lives became stationary as they were on dialysis, and they were ‘not finding space for living’. Suffering is a state of severe distress associated with a threat to the intactness of a person (7). It is a subjective experience unique to the individual (8,9). Based on the concept of “total pain” defined by Cicely Saunders, suffering can be categorized into 4 dimensions—physical, psychological, social, and spiritual (10). Although there were many studies on the suffering experiences of terminally ill patients in the literature, few were about suffering in ESRF patients on dialysis treatment (11-15). The objective of the current study is to explore the experiences of suffering in ESRF patients who are on maintenance dialysis, based on these four dimensions of suffering.

Methods

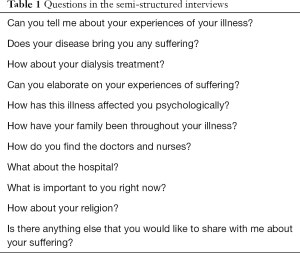

The study was approved by The Ethics Committee of the University of Malaya (MEC No: 866.28) and was conducted in the University of Malaya Medical Centre (UMMC), a tertiary hospital in Malaysia from February 2012 to June 2012. Convenience sampling was used to recruit patients aged 18 years and above, diagnosed with ESRF, and who have been managed on renal replacement therapy (RRT), either hemodialysis (HD) or peritoneal dialysis (PD). Informed consent was obtained from all participants following an explanation of the study. Data were collected using semi-structured interviews by the principal investigator and audio recorded by a trained research assistant. The questions used are listed in Table 1. 19 patients were recruited with an average interview time of 15 minutes per patient.

Full table

Seven interviews in English were transcribed verbatim, whereas 12 Malay transcripts were translated into English. The transcription and translation were done by the principal investigator and the same research assistant, who are proficient in both languages. Thematic analysis was employed through the use of data analysis software NVIVO9. All transcripts were read through repeatedly, with key quotes highlighted, and these were subsequently condensed into codes. Preliminary codes were categorized into four a priori themes of physical, psychological, social and spiritual suffering. Emergent subthemes were recognized by identification of repetitive patterns across the codes. Each subtheme was revised and refined by re-reading the transcripts and the assigned codes to ensure the validity of the study. A literature review was done to substantiate the report write-up. The entire process of thematic analysis was done by the principal investigator, a palliative care physician. Three other palliative care physicians, and two nephrologists, were independently involved in the review and refinement of themes and subthemes.

Results

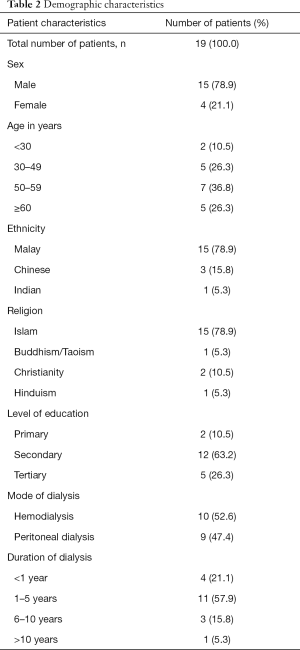

Demographic information of the participants is presented in Table 2. A total of 106 codes were generated with some of the data being double coded if a particular sentence in the transcript contained two experiences of suffering.

Full table

Physical suffering

The two subthemes of physical suffering are (I) physical symptoms and (II) functional limitations. Examples of physical symptoms included pain, breathlessness, oedema, pruritus, lethargy, dizziness, and headache. Patients were affected by pain due to comorbidities and dialysis treatment. Common pain during hemodialysis treatment included arteriovenous fistula pain and back pain due to prolonged sitting. Headache and dizziness were reported when blood pressure was uncontrolled. Breathlessness and oedema due to fluid overload were more commonly reported from peritoneal dialysis patients. Decreased effort tolerance and reduced functional abilities were also reported. Patients were unable to perform routine activities, with special emphasis on the inability to go shopping. Suffering due to multiple hospitalizations, mostly related to infections and PD peritonitis, was described. These hospitalization experiences made some patients feel there were no ending to their suffering, leading some to express their intention to die earlier.

- I have severe pain in the thigh because of ischemia of the muscles; also severe pain in the testis, testis swollen, I went for ultrasound and all these; they said I have ischemia of the testis. (Patient 11, PD)

- So I decided to do CAPD, but you know I am doing quite badly, so the doctor gives me diuretic because I can’t breathe and my heart is having problem in pumping… and I can only walk for about 16 m. (Patient 11, PD)

- According to the doctor, the water that comes out should be more than what I take in, if not, the water will remain in my body. Sometimes it is very bad; I put in 2 L, but it comes out 1 L only. So my legs swell up. (Patient 16, PD)

- Easily tired, before this I was totally fine, I could go shopping, but now I am 50 years old, so I can’t. Usually after coming back from dialysis, I will sleep straight away. Last time when I was strong, I could do many works. (Patient 6, HD)

- The starting is ok, but then it relapses, very troublesome. I understand from the nurse that the bacteria itself is called Pseudomonas, that one very difficult to treat, because a lot of antibiotics don’t work, so myself is the catheter problem (peritoneal catheter), now it comes again, in 2 years I have been admitted 4 to 5 times, I am fed up already. (Patient 16, PD)

Patients were dissatisfied due to their mobility limitation during dialysis. They stopped joining activities as they felt they had ‘lost their daily life’. They stopped shopping and travelling. They were unable to spend enough quality time with families and friends, and were unhappy for having to depend on others for mobility and transport. To avoid troubling families, many patients declined outings and remained at home. They expressed how they missed their previous lifestyle while some had complete loss of interest in their previous hobbies.

Patients also expressed limitation in eating and drinking. They experienced loss of pleasures from eating and drinking caused by their fluid and dietary restrictions. They were scared of the consequences of non-compliance. So, they measured the food and drinks they consumed meticulously. Difficulties in complying with such restrictions during working hours and festive occasions were expressed.

Aside from functional limitations, patients were challenged in managing time between their dialysis sessions and their working time. Although majority of patients were still working when dialysis was started, many lost their jobs subsequently due to failure to adjust their working schedules. Patients described the difficulties in getting a new job due to their situations. Loss of income and the high cost of treatment often left them in a state of financial despair.

- If they go shopping, they will ask me to go along with them. However I usually say never mind, I stay at home. (Patient 7, HD)

- So the discomfort is from the tube which is about 10 cm you know, you can’t go to the toilet or move around your house. I am attached to this tube. (Patient 13, PD)

- Suffer in many ways, one is frustration, because I used to be very active, a person that actively involved in outdoor sport, I race car, I fly plane, I go into the jungle and all that, camping and suddenly all are gone. (Patient 11, PD)

- When I drank lots of water that time, I was scared. I knew I have to control my water intake. I wonder what doctor would do after they know about my high water intake due to fever. (Patient 18, PD)

- Food problem, I can’t drink or eat too much, sometimes very thirsty, but I can’t drink, they limit me to 500 mL per day, I can’t drink more than that. But usually I drink more than that, because 500 mL is too little. So my weight will go up, so they will know I drink a lot. Then also the swelling of my legs. (Patient 16, PD)

- After I work here (canteen), I can’t control my diet. If I am at home, I can control my diet; when I work here, I will be hungry if I don’t eat. (Patient 5, HD)

- Some problem actually, because I have dialysis on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, so I can’t go to work on Tuesday and Thursday. (Patient 10, HD)

- Without this disease, my salary was minimum RM10,000. After I got this, my salary was down to zero, I lost my job… how to survive… you will become stressed, then you will think of all those negative things. (Patient 17, PD)

Psychological suffering

The two subthemes of psychological suffering are (I) the emotions of suffering and (II) the thoughts of suffering. Dialysis patients reacted with different emotions such as anger, frustration, sadness, and worry. Patients were angry at the changes brought by their diseases. They were frustrated because of long hours of sitting during dialysis and the lack of empathy from others. They felt sad for not being able to travel far or enjoy the food they used to enjoy. They felt worthless for not being able to do anything. Their ‘world’ had become smaller. And they have to live with many uncertainties, of themselves and of their families, particularly those with young children. Some worried that nobody would take care of them as their diseases dragged on. Some worried about the lack of efficacy of the dialysis in the future.

- Easily angry, people tried to advise me, but I said “you are not the one who falls sick, so you won’t know how it feels; I am the one who falls sick.” (Patient 2, HD)

- For my world, it has become smaller. My world is like me, nurses, hospital, doctors, antibiotic, operation room, like this, now extra.. the dialysis. My world… I got no more. (Patient 3, HD)

- I think my life is gone. Every day I come here for dialysis only. I think I am tied to the dialysis and I have no real life out there. (Patient 15, PD)

- So the frustration is not being able to do things. I used to run 20 km, but now I am lucky if I can walk 20 steps. (Patient 11, PD)

- My mind keeps asking me, why do you live with this suffering? If we want to live, we must be happy, with aim, goal or something, like I want to be a doctor, buy a car, or buy a house. But now I have nothing. (Patient 3, HD)

- Worry… because my child is still young, I am afraid that if I fall sick, who will be the one to take care of my children. I have one kid only. (Patient 3, HD)

- Of course they are very sad, because only me in my family suffers, only me have this kidney failure, everyone in my family also feels very sad. (Patient 12, PD)

- The fear, because when you do dialysis, you will think of something worse is going to happen. You are scared that the dialysis is not clearing the toxin, then the infection will affect other organs, so you will have fear. (Patient 16, PD)

Non-acceptance and hopelessness were two common thoughts of suffering in patients. Patients found it hard to accept dialysis treatment when they were first told of the bad news. Subsequently, they found it hard to accept the lifestyle changes brought by the disease and dialysis treatment. Some patients regretted for not taking good care of their health previously. It was difficult to come to terms with the suffering caused by their diseases and treatment. Many felt hopeless and wish to die faster because of their suffering.

- At first, I do not know what dialysis is. So when I come for dialysis, I feel I have no hope. (Patient 15, PD)

- We cannot feel sad, it is our fault, we didn’t go to the hospital, didn’t have our body checkup. (Patient 1, HD)

- I just hope I can recover, but I know I can recover for a short period only. I will still suffer, like pain, shortness of breath, easily tired, body ache, and itchiness. (Patient 18, PD)

- But the thing is I just worry that I can’t go (laugh…). I’m just scared that I need to carry on with this for a long time… But as I said I am not afraid to die, I am not afraid of going to another world. I am ready to go. I told my wife I prefer to go… But if it is going downhill, I might as well go fast because the quality of life is not improving. (Patient 11, PD)

- If you know you can only live for one year that is ok. But the thing is you don’t know and if you live until 80–90 years old, then you have to suffer. If you die young it is ok. They can diagnose you with cancer, you have 3 years left. But CAPD no, you can live until 80–90 years old, you suffer. You want to commit suicide but scared. Because you believe in God and God does not allow us to suicide. (Patient 17, PD)

- Then suddenly I want to just end my life, stop dialysis, and let the toxic accumulate in my body. I don’t want to live with this suffering; just the best way is to kill myself. (Patient 3, HD)

Social suffering

The two subthemes of social suffering are (I) healthcare-related suffering and (II) burdening of others. In Malaysia, dialysis is paid by patients themselves unless they are government servants in which their dialysis cost will be borne by the government. The costly treatment for ESRF was a recurrent motif in the interviews. Unaffordable medical expenses burdened ESRF patients alongside the hardships from illness. Expenses were mainly from HD treatment, equipment for PD, other consumables such as sanitizers and dressing sets, as well as transportation fees to the hospital. Patients described that ‘this is the disease that rich people get’ and ‘it is as expensive as sending a child to study overseas’. Not all patients were able to get subsidies from medical social welfare or sought reimbursements from the Social Security Organization (SOCSO).

- I find this kidney disease quite an expensive disease. If government doesn’t help, quite a lot of people will be asking for donation because we have no money to pay. RM2600 per month you know, even for CAPD. We earn also not even RM2000, how to survive? (Patient 16, PD)

- Sometimes doctors want us to buy certain medicine outside; we are lack of financial capability to do so. At first I will buy the medicine, but this can’t last long. Just imagine if you need to take that medicine every day and each day RM7, one month will be how much? How about one year? (Patient 14, PD)

Another issue raised by the patients receiving peritoneal dialysis was related to the additional work to maintain a clean environment for dialysis. It was a crucial step to prevent infection, however not all patients were fit enough to do it themselves, which added to their dependency on family caregivers. Apart from that, the dialysis, while a life-saving treatment, also represented a nuisance. Patients complained that 6-hourly peritoneal dialysis sessions were tedious and taxing, leading some to become non-compliant.

- Take the solution back also heavy, sometimes take 2–3 bags, I usually borrow the trolley here. …For the dialysis you need a storage place, to store the Baxter, every day they will send you 20 boxes, the 10L one. Then you need to keep the machine, the dressing set, the tube, one big box you know. (Patient 17, PD)

- I have to do CAPD every 6 hours. When you go back home, you have to do CAPD, have to wash the equipment, throw away the bag and repack all the things, all these become a routine now. (Patient 19, PD)

Most patients were dissatisfied with their intermittent hospital stays. Some felt uncomfortable as the wards were congested. The unfamiliar hospital environment often resulted in sleepless nights. Hospital food was lacking in variety and not up to their expectations. One patient described difficulties accessing the hospital pharmacy, which was especially challenging for elderly people with limited mobility. Another patient grumbled about the lack of hospital parking spaces. Besides hospital facilities, several patients complained about the healthcare providers. The lack of opportunities to meet doctors and the long waiting times for consultations upset the patients. One patient questioned the competency of a certain doctor, and criticized the lack of coordination between different teams.

- You feel you are not at home. You are a patient, and you see row of patients, beds and all that. The environment is different. (Patient 13, PD)

- I felt difficult to sleep in the hospital. The bed was too high, couldn’t be lowered. I slept a while then woke up. (Patient 18, PD)

- Never mind, she was incompetence, she didn’t even know how it works, I told her it is not working, she was stubborn, she wouldn’t listen. … You doctors are supposed to work as a team, for the sake of the patient. If you start talking bad about other members of your team, your patient will not get very confident of your hospital. (Patient 11, PD)

Burdening of others was another source of suffering for ESRF patients. Many patients depended on family members for financial support, mobility assistant and transport. Some patients were frustrated for their inability to perform basic activities of daily living, hence burdening their loved ones. It wasn’t easy to witness the stress and exhaustion of family members who tried to accommodate their needs. One patient expressed great concern over the heavy load of his spouse due to the change of role within the family.

- But the trouble is my wife has to be the sole breadwinner. She has to rush out early in the morning and come back late at night. She is already tired. If I ask her to do a lot of work, I’m afraid she might collapse. So there are actually a lot of things that pile on her. Then my daughter is also busy so she can’t help her much. So I am worried that if she collapses, who will be the one to look after all of us. (Patient 11, PD)

- They all also suffer because one of their family members suffers. Of course they also have to contribute their time, money, and of course my family members care about me. Now, they focus on me, concentrate on me, also my brother has decided to become the donor for me. (Patient 12, PD)

Spiritual suffering

The query of suffering is the only subtheme in spiritual suffering. Irrespective of religious beliefs, many ESRF patients doubted the purpose of their lives. Many asked why they had to suffer, and why were they the chosen ones? They felt helpless and hopeless. They were uncertain about what would happen next and when would be the end of their suffering. Accepting the reality of their situations was tough. Having no choice, many chose to accept their suffering as their fate or as a test from God. Several patients believed that their disease was a punishment from God.

- My mind keeps asking me, why do you live with this suffering? (Patient 3, HD)

- My whole family didn’t get this, why should I? (Patient 4, HD)

- This thing, actually we just accept it, we cannot do anything, so we just let God decides, maybe this is our fate. (Patient 1, HD)

- Maybe because we are bad sometimes, so our God wants to give us some challenges, wants to test us. (Patient 8, HD)

- This disease actually happened to us, is our ‘dosa’ (sin), we are supposed to control our diet, as a Muslim we should take care of our diet, activity, spirit, ‘puasa’ and others. (Patient 1, HD)

Discussion

Compared to the average age of 60’s of dialysis populations in the developed world, our dialysis population is young because of the high prevalence of diabetic kidney disease and the low transplant rate due to resources problem. But despite significant advances in renal replacement therapy, our ESRF patients still suffer tremendously. Patients on dialysis were referred to palliative care less often than those with cancers even though their 5-year survival rate was lower than many forms of cancer (16). To improve the situation, renal physician should recognize the unrelieved suffering of dialysis patients and refer them EARLY to palliative care.

Based on the WHO definition of palliative care which emphasizes the prevention and relief of suffering, the need to incorporate palliative care early into the medical management of ESRF patients has been highlighted in recent researches. Palliative care interventions such as symptoms control, psychosocial support and advance care planning could be started even before the commencement of dialysis (6). References could be taken from other fields or models of collaborative palliative care delivery to maximize successful palliative care integration (17,18).

Timely advance care planning is essential to improve the quality of life of renal patients (19). Patients preferred earlier discussion of advance care planning; however, such planning is currently sub-optimally practiced in Malaysia (20). Furthermore, referrals to specialist palliative care services are often late and centered on discussions regarding dialysis withdrawal. Multidisciplinary collaboration between nephrology, palliative care, nursing, and social welfare are highly important in providing patient-centered renal care.

It is well-recognized that ESRF is a life-limiting condition which affects various aspects of patients’ lives. Physical suffering encompassed both physical symptoms and functional limitations which resulted from the disease and its treatment. The uraemic symptoms commonly associated with ESRF such as fatigue, pruritus, and dyspnoea, were consistently reported in this and previous studies, posing a huge negative impact on patients’ quality of life (21-23). Some of these issues with poor dialysis results such as fluid retention could be related to inadequate education on proper peritoneal dialysis technique due to low nurse-to-patient ratio of 1:50, non-compliant lifestyle, and the high prevalence of heart failure. Pain was a prevalent symptom that should not be overlooked in the quality care of dialysis patients (24,25). Similar to our findings, a previous study reported that the majority experienced significant musculoskeletal pain, headaches, as well as access-related pain such as pain in the fistula hand due to regular needling of the fistula (26). The high symptom burden and its adverse impact on ESRF patients were found to be comparable or even greater than those with malignant conditions (27,28). This highlights the importance of early collaboration with palliative care for better symptom control and delicate fistula care to improve the quality of life of dialysis patients.

Another essential finding was that hospitalizations due to recurrent complications such as peritonitis and other comorbid conditions was an important source of suffering in patients receiving PD. Two patients stated that they were troubled by their treatment-resistant infections which led to the removal of their Tenckhoff catheters. Peritonitis has been a leading cause of PD failure which accounted for 13% in Malaysia, as well as having significant impact to the mortality in PD patients (2,29,30). In addition, recurrent peritonitis was associated with higher ultrafiltration problems, higher rate of permanent PD discontinuation, and overall poorer outcome (31,32). Hence, apart from the appropriate treatment of infections, preventive measures should be given priority too to reduce the infection rates. In regards to that, infection control protocols such as proper catheter placement, routine exit-site care, and careful training for nurses and patients should be reinforced strictly (33-35).

The time-consuming treatment and restricted lifestyle were repetitively described in this study and other studies (3,4). The hemodialysis machine was portrayed as the ‘mechanical lifeline’ that was inseparable from their lives (36). While previous studies focused mostly on HD patients, our findings revealed that HD or PD patients endured similar life disruptions. This suggested that the limitations were related to the physical condition rather than the dialysis modalities. With advances in technology, there is a shift from continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) to automated peritoneal dialysis (APD). APD which is performed at night may provide more space of living for patients and allow more time for work, family, and social activities (37). For HD, establishing more dialysis centers equitably across the country may reduce the lengthy travelling time of patients.

Frustration due to the fluid and dietary restrictions was greatly emphasized by our study patients. Many found it hard to endure their thirst and abstain from consuming foods they enjoyed. Consistent with other studies, most patients had difficulty to cope with their restrictions, leading to non-adherence (38-40). One study pointed out the reasons for non-adherence which included the lack of knowledge and understanding of the importance of adherence, forgetfulness, and lack of self-control (41). Patients with chronic diseases appeared to prioritize quality-of-life over treatment adherence which was in contrast with the desired outcome of healthcare professionals (42).

Psychological suffering was closely related to patients’ poor physical conditions. Patients experienced various emotional disturbances and negative thoughts while facing life transitions in ESRF (6). This could be understood through the illness intrusiveness concept whereby disease and treatment impacted on subjective well-being, affecting the psychosocial outcomes (43). In our study, the common emotional reactions evident were anger, frustration, sadness, fear, and worry. A previous study done on cancer patients also reported similar emotional processes, however, the patients in this study did not mention shock or surprise (44). This may be due to the indolent nature of the disease. Most patients would have been informed earlier about the progression and the potential need for renal replacement therapy during various stages of their chronic kidney disease. Different from other studies in which ESRF patients hoped for a cure while on the waiting list of renal transplant, none of our patients talked about transplant. This might be due to the low volume of renal transplant in Malaysia (2,4). Nonetheless, hope was found to be an essential component for patients in dealing with illness experiences, as well as for healthcare providers in planning the care for patients with chronic illnesses (4,45-47).

Social suffering in this study was attributed to the healthcare and dependency on others. Despite the subsidies and reimbursements offered, the high treatment cost of dialysis is often beyond the capability of average individuals and this eventually becomes a barrier for receiving renal replacement therapy in Malaysia (48-50). Hence, the economic evaluation of dialysis requires more attention and consideration from policy makers and the government to ensure cost-effectiveness. Several patients uttered dissatisfaction towards hospital facilities and certain healthcare personnel. The unpleasant experience described was echoed in a previous report whereby health care interaction became a source of suffering to patients (51). This highlights the importance of patient-centered care versus a diagnosis-centered approach. Another aspect of social suffering reported by our patients was care dependence due to loss of functions. Patients struggled between the fear of burdening of others and the fear of being abandoned (52).

Spiritual suffering occurred when patients were perplexed by various questions about life, suffering and death, and perceived loss of purpose and meaning in life. On the trajectory of ESRF, some patients experienced self-blaming which were in line with one study where patients believed in retribution and regarded their disease as the end result of their previous sins (53). None of our patients mentioned about religious support contrary to other studies where religious faith was a way of coping (54,55). Spiritual care is an integral component of holistic care (56). Fostering spirituality and creating a healing environment are essential for patients undergoing dialysis.

Although conservatively-managed ESRF patients are often referred to palliative care, there isn’t a mechanism to transition dialysis patients to receive palliative care. Renal physician should consider referring dialysis patients with unrelieved physical, psychosocial or spiritual suffering to palliative care early.

There were several limitations in this study. Due to small sample size and convenience sampling in a single center, our patients may not represent the general population in Malaysia. The findings were also limited by the scope of interview questions. Translations of the 12 Malay interviews might miss some subtle experiences of suffering shared by patients. Further studies could be done to explore suffering experiences of each major transition such as starting of dialysis, preparation of vascular access, changing of dialysis modality, and the struggles from recurrent admissions. Sociocultural factors that affect the coping mechanism could be explored. Studies to find out the effectiveness of early renal palliative care, the barriers of renal palliative care and spiritual care are needed to fill in the gaps between evidences and clinical practice.

The awareness of renal palliative care is growing but there is currently not a single model for the delivery of such holistic care. Starting palliative care early with stepwise support aiming at the various struggles of ESRF patients in each transition can be useful. We believe that timely and good renal palliative care would alleviate the suffering of ESRF patients and improve their quality of life.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our heartfelt gratitude to all patients who have participated in the study.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Malaya (MEC No: 866.28) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

References

- Thomas B, Wulf S, Bikbov B, et al. Maintenance Dialysis throughout the World in Years 1990 and 2010. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;26:2621-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goh BL, Ong LM, Lim YN. 21 Report of the Malaysian Dialysis and Transplant Registry 2013. Kuala Lumpur 2014. Available online: https://www.crc.gov.my/wp-content/uploads/documents/report/21stdialysis_transplant_2013.pdf

- Hagren B, Pettersen IM, Severinsson E, et al. Maintenance haemodialysis: patients’ experiences of their life situation. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:294-300. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herlin C, Wann-Hansson C. The experience of being 30-45 years of age and depending on haemodialysis treatment: a phenomenological study. Scand J Caring Sci 2010;24:693-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ginieri-Coccossis M, Theofilou P, Synodinou C, et al. Quality of life, mental health and health beliefs in haemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients: investigating differences in early and later years of current treatment. BMC Nephrol 2008;9:14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson TA. Transitions in the lives of patients with End Stage Renal Disease: a cause of suffering and an opportunity for healing. Palliat Med 2005;19:270-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cassel EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med 1982;306:639-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodgers BL, Cowles KV. A conceptual foundation for human suffering in nursing care and research. J Adv Nurs 1997;25:1048-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Byock IR. The nature of suffering and the nature of opportunity at the end of life. Clin Geriatr Med 1996;12:237-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saunders C, Baines M. Living with Dying:The Management of Terminal Disease. 1st ed. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1983.

- Murata H, Morita T. Conceptualization of psycho-existential suffering by the Japabese Task Force: the first step of a nationwide project. Palliat Support Care 2006;4:279-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morita T. Existential concerns of terminally ill cancer patients receiving specialized palliative care in Japan. Support Care Cancer 2004;12:137-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blinderman CD, Cherny NI. Existential issues do not necessarily result in existential suffering; lesson from cancer patients in Israel. Palliat Med 2005;19:371-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beng TS, Guan NC, Seang LK, et al. The experiences of suffering of palliative care patients in Malaysia: a thematic analysis. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2014;31:45-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilson KG, Chochinov HM, McPherson CJ, et al. Suffering with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:1691-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC, et al. US Renal Data System 2017 Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2018;71:A7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng HW. Optimizing end-of-life care for patients with hematological malignancy: rethinking the role of palliative care collaboration. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;49:e5-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chan KY, Yip T, Yap DY, et al. Enhanced psychosocial support for caregiver burden for patients with chronic kidney failure choosing not to be treated by dialysis or transplantation: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis 2016;67:585-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bristowe K, Horsley HL, Shepherd K, et al. Thinking ahead--the need for early Advance Care Planning for people on haemodialysis:A qualitative interview study. Palliat Med 2015;29:443-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goff SL, Eneanya ND, Feinberg R, et al. Advance care planning: a qualitative study of dialysis patients and families. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015;10:390-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Janssen DJ, Spruit MA, Wouters EF, et al. Daily symptom burden in end-stage chronic organ failure: a systematic review. Palliat Med 2008;22:938-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murtagh FE, Addington-Hall J, Higginson IJ. The prevalence of symptoms in end-stage renal disease: a systematic review. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2007;14:82-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davison SN, Jhangri GS. Impact of pain and symptom burden on the health-related quality of life of hemodialysis patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010;39:477-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weisbord SD, Carmody SS, Bruns FJ, et al. Symptom burden, quality of life, advance care planning and the potential value of palliative care in severely ill haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2003;18:1345-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Kader K, Unruh ML, Weisbord SD. Symptom burden, depression, and quality of life in chronic and end-stage kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2009;4:1057-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davison SN. Pain in hemodialysis patients: prevalence, cause, severity, and management. Am J Kidney Dis 2003;42:1239-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saini T, Murtagh FE, Dupont PJ, et al. Comparative pilot study of symptoms and quality of life in cancer patients and patients with end stage renal disease. Palliat Med 2006;20:631-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sprangers MA, de Regt EB, Andries F, et al. Which chronic conditions are associated with better or poorer quality of life? J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:895-907. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akoh JA. Peritoneal dialysis associated infections: An update on diagnosis and management. World J Nephrol 2012;1:106-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li PK, Szeto CC, Piraino B, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations:2010 update. Perit Dial Int 2010;30:393-423. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lane JC, Warady BA, Feneberg R, et al. Relapsing peritonitis in children who undergo chronic peritoneal dialysis:a prospective study of the international pediatric peritonitis registry. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:1041-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jose MD, Johnson DW, Mudge DW, et al. Peritoneal dialysis practice in Australia and New Zealand: a call to action. Nephrology (Carlton) 2011;16:19-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bender FH, Bernardini J, Piraino B. Prevention of infectious complications in peritoneal dialysis: best demonstrated practices. Kidney Int Suppl 2006.S44-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho Y, Johnson DW. Peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis: towards improving evidence, practices, and outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis 2014;64:278-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Piraino B, Bernardini J, Brown E, et al. ISPD position statement on reducing the risks of peritoneal dialysis-related infections. Perit Dial Int 2011;31:614-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hagren B, Pettersen IM, Severinsson E, et al. The haemodialysis machine as a lifeline: experiences of suffering from end-stage renal disease. J Adv Nurs 2001;34:196-202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bro S, Bjorner JB, Tofte-Jensen P, et al. A prospective, randomized multicenter study comparing APD and CAPD treatment. Perit Dial Int 1999;19:526-33. [PubMed]

- Mellon L, Regan D, Curtis R. Factors influencing adherence among Irish haemodialysis patients. Patient Educ Couns 2013;92:88-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee SH, Molassiotis A. Dietary and fluid compliance in Chinese hemodialysis patients. Int J Nurs Stud 2002;39:695-704. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seah AC, Tan KK, Huang Gan JC, et al. Experiences of Patients Living With Heart Failure:A Descriptive Qualitative Study. J Transcult Nurs 2016;27:392-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lam LW, Lee DT, Shiu AT. The dynamic process of adherence to a renal therapeutic regimen: perspectives of patients undergoing continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Int J Nurs Stud 2014;51:908-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vermeire E, Hearnshaw H, Van Royen P, et al. Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J Clin Pharm Ther 2001;26:331-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Devins GM. Using the illness intrusiveness ratings scale to understand health-related quality of life in chronic disease. J Psychosom Res 2010;68:591-602. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tan SB, Loh EC, Lam CL, et al. Psychological processes of suffering of palliative care patients in Malaysia:a thematic analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2019;9:e19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duggleby W, Hicks D, Nekolaichuk C, et al. Hope, older adults, and chronic illness: a metasynthesis of qualitative research. J Adv Nurs 2012;68:1211-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Forbes MA. Hope in the older adult with chronic illness: a comparison of tow research methods in theory building. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 1999;22:74-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davison SN, Simpson C. Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease:qualitative interview study. BMJ 2006;333:886. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hooi LS, Lim TO, Goh A, et al. Economic evaluation of centre haemodialysis and continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis in Ministry of Health hospitals, Malaysia. Nephrology (Carlton) 2005;10:25-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mushi L, Marschall P, Flessa S. The cost of dialysis in low and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:506. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li PK, Chow KM. The cost barrier to peritoneal dialysis in the developing world--an Asian perspective. Perit Dial Int 2001;21 Suppl 3:S307-13. [PubMed]

- Beng TS, Guan NC, Jane LE, et al. Health care interactional suffering in palliative care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2014;31:307-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Strandberg G, Astrom G, Norberg A. Struggling to be/show oneself valuable and worthy to get care. One aspect of the meaning of being dependent on care--a study of one patient, his wife and two of his professional nurses. Scand J Caring Sci 2002;16:43-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin CC, Chen MC, Hsieh HF, et al. Illness representations and coping processes of Taiwanese patients with early-stage chronic kidney disease. J Nurs Res 2013;21:120-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wu CC, Lin CC, Hsieh HF, et al. Lived experiences and illness representation of Taiwanese patients with late-stage chronic kidney disease. J Health Psychol 2016;21:2788-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clarkson KA, Robinson K. Life on dialysis: a lived experience. Nephrol Nurs J 2010;37:29-35. [PubMed]

- Egan R, Wood S, MacLeod R, et al. Spirituality in Renal Supportive Care: A Thematic Review. Healthcare 2015;3:1174-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]