Perinatal bereavement and palliative care offered throughout the healthcare system

Background

The loss of a dreamed for pregnancy/child is both a physiological event for a woman as well as an emotional and sociocultural one. Women often form attachments to their child early in the pregnancy and therefore a pregnancy loss can be emotionally devastating regardless of the gestational age of the fetus (1). Early pregnancy loss, also referred to as spontaneous abortion or miscarriage, occurs in 10% of known pregnancies and occurs in the first 13 weeks of pregnancy (2). Perinatal mortality is the combination of fetal deaths and neonatal deaths (3). In the United States the fetal mortality rate for gestations of at least 20 weeks is similar to the infant mortality rate, 5.96 deaths per 1,000 live births and 5.98 infant deaths per 1,000 live births respectively (4). Fetal mortality accounts for 40–60% of perinatal mortality (3). The term stillborn may be used to describe fetal deaths at 20 weeks’ gestation or more.

Women who experience early pregnancy loss, or a fetal or infant death, may interface with the health care system in a variety of ways and receive services from multiple personnel from many disciplines. Women with a loss may be seen in the health care clinic, prenatal office, emergency department (ED), the operating room (OR), the maternal-child services department, the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), and/or the palliative and hospice service lines. Women and their families may encounter personnel from across the health care system, such as chaplaincy, social service workers, genetic counselors, and support staff.

Organizations such as the Institute of Medicine (5) and the American Academy of Pediatrics have expectations that end of life care will be delivered with quality (6). Provision of high quality, consistently provided bereavement care creates a culture of compassion and can improve the patient and family experience. Bereavement services have the potential to impact the metrics of healthcare systems by improving patient outcomes and satisfaction (7). The aims of this article are twofold: (I) provide a general overview of perinatal bereavement services throughout the healthcare system; and (II) identify future opportunities to improve bereavement services, including providing resources for the creation of standardized care guidelines, policies and educational opportunities across the healthcare system.

Maternal child services

Maternity care services include prenatal care, labor and birth, and postpartum care of a woman. Health care approaches incorporate physical, psychosocial and cultural needs of the woman and her chosen family members. Fetal surveillance and interventions are provided prenatally and during the labor process followed by neonatal assessment and treatments following the birth.

For decades nurses in the maternity care services have sought ways to provide evidence-based bereavement care to families experiencing pregnancy loss. Led by the work of nurse scientists, psychologists and other experts, nurses and their professional colleagues often complete education to promote relationship-based, patient-centered services between bereaved parents and themselves through organizations such as Resolve Through Sharing (RTS) who has hosted over 50,000 professionals worldwide (8), and Perinatal Loss and Infant Death Alliance (PLIDA) (9). Many professionals in maternity services cultivate their expertise via patient-care experiences and formal and informal education and training. Standardized bereavement guidelines are often available in the maternal-child unit and are guided by recommendations from a variety of national organizations, such as RTS (8) and PLIDA (9). The following list provides an overview of recommendations for bereavement services.

- Assess parental desires for special end-of-life (EOL) rituals, such as spiritual practices (blessings, baptisms) and cultural preferences (family presence, feeding), which enables providers to tailor interventions. For instance, assessing parental desire to spend time or conduct rituals with their infant after death enables providers to offer specific available services. One recent growing trend in perinatal bereavement care is the availability of a cooling system embedded in to a bassinet that enables the deceased infant to remain with parents for a longer period of time (10). Such a device can provide clinicians with additional time to assess parental wishes and support women who have had unexpected surgery, a slow birth recovery, or who are in emotional shock.

- Ensure support for parental caregiving, such as holding, rocking, cuddling the infant, as well as providing hands-on care such as bathing, dressing and feeding as a standard of care (11).

- Provide options for parents regarding the collection and offering of mementos, such as locks of hair, plaster molds of hands or feet, handprints, footprints, blankets, or a special stuffed toy upon discharge.

- Photographs allow families to have a special remembrance of their child. In a study of 104 families regarding photography after perinatal loss, Blood and Cacciatore found that 98.9% of parents who had photographs endorsed them and for the 11 parents who did not have photographs, 9 wanted them (12). Professional photography services such as “Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep” (13) are available in most locations throughout the country. Support can be offered for parents who wish to take their own photographs. It is recommended that permission is sought before staff members take these pictures.

- During the postnatal period following discharge, parents may appreciate follow up contact in the form of cards, phone calls, and invitations to annual remembrance ceremonies.

Perinatal palliative care (PPC) is a newer development in maternity services which is a family-centered approach that augments maternity care with emotional, sociocultural and spiritual support for parents who are continuing a pregnancy affected by a life-limiting fetal condition. When such a diagnosis is made parents have an opportunity to participate in making plans, which can give them a sense of control as the pregnancy and birth progress. Programs across the United States assist families by providing support, anticipatory guidance and the creation of birth plans that are tailored to parents’ personal needs and desires (14). Advance care planning is a goal of PPC and includes the opportunity for parents to discuss concerns and hopes with their health care providers (HCPs). Women may explore options whether to have a vaginal or cesarean birth.

Advance care planning includes conversations about the newborn as well. Topics such as administering or withholding medical treatments are addressed and families can express how they want to spend the final days and hours with their infant. A birth plan must be flexible to account for potential variance in outcomes and should include the physical and comfort needs of the infant as well as the existential need to be loved. Birth plans should be documented and included in the medical record so that all HCPs can access and respect them. The reader is directed to two resources for further information. English and Hessler describe use of a perinatal birth plan (15) and Ruiz Ziegler (16) provides a video to show staff how PPC can be delivered.

A recent national survey confirmed the interdisciplinary nature of PPC and noted that the vast majority of programs have a coordinator of care (17). PPC program leaders report providing robust support for many bereavement interventions like those listed above. Important components of PPC include (I) respect for parent preferences and choices; (II) provision of compassionate, holistic care; (III) respect for the infant; and (IV) facilitation of opportunities to parent the infant and cherish time together as a family (18).

Neonatal intensive care

Admission of neonates in to the NICU is associated with parental stress, anxiety, loss of control and depression (19). Parents are confronted with a critical care environment that may lend itself to feelings of physical and emotional isolation from their baby. It is known that parents experience loss and grieve when their infant is admitted to the NICU (20). Parents may grieve the lack of opportunities to immediately provide care and comfort to their baby and they may mourn their limitations to physically and emotionally nourish their baby. They may grieve the unexpected illness or premature birth and worry about their child’s wellbeing. Coming to terms with a NICU admission may take time, and the provision of family-centered support, which includes anticipatory guidance and bereavement principles, is recommended (6).

The goal of the NICU is to cure children who are ill and/or restore their health so that they can grow up to have quality of life. Sometimes, the curative goals of the NICU cannot be achieved and neonates may need a combination of therapeutic and palliative interventions. Although an integrated intervention approach can reduce cost (21) and is recommended (6), it is not currently the norm in health care systems (22). Unfortunately, in many instances, palliative care is offered sporadically and, in many cases, very late in the EOL trajectory. Similar to bereavement care in maternal child services, parents whose infant dies while in a NICU can benefit from the following: consistent, compassionate communication; participation with bereavement rituals; family presence and support; anticipatory guidance; referral to psychosocial support; counseling; follow-up contact (7).

Palliative care can be offered in settings other than a NICU. The seminal work of Catlin and Carter in 2002 laid a foundation for EOL care for neonates in and out of a hospital setting (23). Infants may need EOL care in the labor and delivery suite or a newborn nursery. If discharged, infants may qualify for hospice care, which can be delivered in the patient’s home or in a community hospice especially suited for pediatric patients. Hospice is a distinct Medicaid or Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) benefit which can be coupled with curative measures. The Affordable Care Act requires physician certification that a child is within the last 6 months of life if the disease runs its normal course (24). Regardless of where perinatal bereavement services are given, parents need a great deal of support and compassion as they navigate the emotional stressors of their child’s EOL care and the possible psychosocial trauma such loss entails. The video Choosing Thomas (25) provides real life filming of hospice care at home and death of a cherished newborn.

Outpatient services

Prenatal clinics

Although staff members working on inpatient maternal child units are well trained in pregnancy loss care, many other departments focus on physiological concerns and have been less educated about the support, dignity and comfort that the woman and her family may need. For those working in prenatal clinics, a routine visit may swiftly become one needing consoling for the patient and family. The assessments conducted at prenatal visits may reveal an unexpected loss when the fetal heartbeat cannot be heard or visualized. Women may present to the prenatal clinic aware that something is amiss, with bleeding that is a result of a pending or complete miscarriage. At times, women may note a cessation of fetal movement which ultrasonography may confirm as a fetal demise.

All of these clinical scenarios may be devastating for the patient and very difficult for the staff who must deliver bad news (26). Families appreciate the physician’s, nurse’s or midwife’s advocacy and presence. If a loss has occurred or is anticipated, one role of the nurse is to prepare women about what the delivery will be like (medical or surgical) and what can be expected regarding the look of the fetal remains. Giving women permission to choose what is most comfortable to them regarding touching or viewing the remains is appropriate, as is giving women permission to forego such actions. In the case of a later pregnancy loss, nurses can provide guidance about admission to the hospital or birthing center and prepare women for the procedures that may be a part of the delivery and post-birth (27).

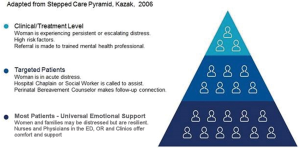

When a baby is lost, grieving by the family may be intense. The clinic nurses and ultrasonographers may lack training in what and what not to say, and how to provide comfort. Greiner et al. (28) advises the use of the SPIKES model, using the setting, perception, invitation, knowledge, empathize, summary, and strategy. Use of “I wish” statements, such as “I wish my news were better,” “I wish this had not happened,” “I wish I could offer you comfort,” is advised. Simpson and Bor (29) advise having a protocol to follow when ultrasound determines fetal death. The Kazak stepped pyramid in Figure 1 (30) depicts a method for knowing when to refer forward for intense grief. Letting the whole team know by signifying with a certain symbol on the chart or office door is recommended. From the housekeeper to the pharmacist dispensing medications, expressing condolences for a pregnancy loss is an important comfort measure.

Staff members in prenatal and gynecology clinics who are developing mastery in bereavement service are making follow up phone calls and sending bereavement cards signed by physicians, nurses and staff. Staff members coordinate with the local labor and delivery services for memento making as indicated. A fully supportive clinic would also have a chaplain on call.

ED

Women experiencing a miscarriage (spontaneous abortion, complete abortion, blighted ovum) most often present to the ED. Unless the patient is unstable, a miscarriage is considered nonemergent, relegating women to potentially long wait times. ED personnel are accustomed to managing many ongoing clinical demands and may overlook the psychological impact of pregnancy loss. The recently published “Interdisciplinary Guidelines for Care of Women Presenting to the Emergency Department with Pregnancy Loss” (31) outlines consensus-driven guidelines on how to care for women presenting to an ED with an actual or impending loss of pregnancy. The Guidelines discuss that for some women, this may be an “emotional trauma” and considered as painful as the loss of a child. Components of the 27 items include assessment for meaning of loss to woman, meeting physiological needs with an emotional support component, how to handle the incomplete miscarriage at home, suggested verbiage to guide difficult discussions about the viewing and handling of remains, respectful disposition of products of conception with family choice, use of photography, creating mementos, community resources, garnering administrative backing and debriefing staff in difficult cases. Without the implementation of such guidelines, MacWilliams and associates’ (32) findings confirm that women leave the experience in the ED lacking instructions and clarity on follow-up and have a sense of feeling marginalized.

OR

The OR become involved when a woman experiences miscarriage bleeding that is excessive, a fetal demise, an ectopic pregnancy, a molar pregnancy, or the provision of a cesarean section for a newborn with a life limiting condition. Healthcare professionals’ education should be consistent so that all families with a pregnancy loss are comforted in the same way, including in the OR. The woman should be asked “How do you view what happened with your pregnancy?” If even at an early gestational age they feel they have lost a child, support for the loss is essential. Again, how the fetal remains are treated by the health care personnel is important and should be managed with the utmost respect and dignity. Women with an early pregnancy loss should be asked if they wish to view the fetal remains. For later losses, parents may wish to receive mementos of the pregnancy such as hand or foot prints of their fetus or child, or to hold or dress the child if the size and condition allows. Ruiz Ziegler (16) has created an educational film for the OR on offering bereavement support for the family whose infant is expected to die at the time of cesarean birth.

Additionally, women experiencing pregnancy terminations for their own health or for fetal anomalies require management with dignity and support. All families should be offered bereavement care for grief that they may feel. This may have also been a desired pregnancy that a woman cannot support due to her own medical condition or that of the fetus. This may have been a pregnancy unsupportable psychologically, such as from violence (33) or while in poverty. Some nurses find participating in pregnancy termination for whatever cause to cause moral distress. Catlin (34) has discussed perinatal loss and bereavement in the perioperative services and defines the process for the nurse who may wish to conscientiously object yet still care. In this paper, Catlin uses the Codes of Ethics from the American Nurses Association, the American Society of PeriAnesthesia Nurses and the Association of periOperating Room Nurses to delineate that specific therapeutics, but not specific patients, may be objected to. The need for bereavement support from all nurses for all patients, outside of participation in the surgical procedure, is essential.

Ethics committee

The Joint Commission requires that all hospitals have access to experts who can help resolve ethical dilemmas for patients, families or staff. When conflict in a perinatal situation arises, especially over end of life care, the ethics consultant is called. Conflict may occur when goals of staff differs from goals of the family, or one family member’s wishes may differ from that of another family member. Catlin (35) discusses using evidence and position statements from professional organizations, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the National Perinatal Association, or the American Nurses Association to assist the committee deliberation. Berger (36) and Wocial and colleagues (37) discuss how important it is to include an ethicist in staff meetings, morning rounds, and conversations. Members of the ethics committee are often trained to offer debriefing after a complicated or tragic maternal or fetal death. Often these services may overlap with chaplaincy services or the palliative care team. The ethics team should be familiar with issues of conscientious objection and patient abandonment on the OR (34).

Chaplaincy services

Chaplains are accustomed to comforting families of adult patients in the hospital before and after deaths occur. In a study of maternal child nurses (38), 100% of nurses wanted a chaplain present at a perinatal loss. For chaplains, many of the same concepts apply as in ministering for an adult loss, but in pregnancy loss there is often added component. Women often experience guilt that they may have done something to ‘cause’ the loss. The chaplain is an active listener offer solace from a secular, religious, spiritual or cultural view. Chaplain activities include relationship building, care at the time of death, helping patients and families with existential issues or spiritual distress and addressing goals of care (39). Chaplains have developed rituals such as blessings and prayers after a perinatal loss (40).

Palliative care team

Palliative care teams usually include a physician, nurse, social worker and chaplain. They assist in establishing patient goals and helping shape the plan of care to be delivered by the providers. Teams which exist outside of children’s hospitals most often are trained to serve adult patients well. Dickinson (41), in a history of teaching end of life care in medical school, describes 40 years of training in end of life and geriatrics, and does not include any mention of pediatrics or perinatal end of life training. The team may lack experience, training, funding or desire to serve the perinatal community. In a study of clinicians by Verberne and colleagues (42), a barrier to the use of pediatric palliative care was limited understanding of what such services could do for them. Yet the adult team, who are comfortable in discussing end of life issues, could be very helpful to other providers delivering care for impending perinatal loss. Integration of perinatal bereavement to the hospital palliative care team would elevate the system wishing to provide the highest level of services to the community. Carter et al. (43) have authored an instructive handbook for the new field of perinatal and pediatric palliative care. This text could assist those palliative care team members who have done only adult palliative care.

Recommendations

Education and training

Education and training that teach optimal methods of communication with parents who are in distress are a priority. Regardless of the departmental setting, clinicians should have access to evidence-based information on how to communicate with parents. Hall and colleagues’ (44) suggestions for psychosocial support in neonatal units can be used in additional locations. Hall tells us that pregnancy loss or giving birth to an infant with a life-limiting condition may cause mood disorders and anxiety. She recommends family-centered developmental care, based within the family’s culture, and appropriate methods of communication. Several organizations in the United States have created curricula focused on bereavement care. Nurses can receive specialized training or certification by organizations such as RTS (8), PLIDA (9), and ELNEC (End of Life Nursing Education Consortium) (45).

Creation of standards, policies, and written information for parents

Evidence is available, and has been referred to within this article, that can be used to create bereavement-based policies for a healthcare system. Assessing parental wishes and needs is an important first step. Having verbiage and guidelines that address the sensitive issues of respectful disposition of remains should be included in policies. Readers are referred to the work of Levang and colleagues (46) for clinical practice recommendations. Providing parents with written information allows them to review instructions and access contact information post-discharge. Standards of care should also address ways to provide parents who desire it with mementos of their pregnancy.

Further support for parents

There is a wide range of emotions amongst those with pregnancy loss which may not be connected with gestational age. Use of the adapted stepped care pyramid by Kazak et al. (30) in Figure 1 will provide guidance for behavioral health referral and treatment. Preliminary screening for grieving may indicate that the onsite staff can handle providing comfort. Additionally, recommending a pregnancy loss organization such as SHARE (www.nationalshare.org) or a phone application such as The Miscarriage App (mobile phone app for iPhone and Android phones) can be helpful. Community referrals and support (support groups, live and online) can make a difference in recovery.

Part of a full-service perinatal bereavement support program is a special Health System Remembrance Event. This may be combined with an event for adult deaths or specific to infants and pregnancies. If the reader’s own hospital does not convene such a day, it is prudent to check with other hospitals in the healthcare system to explore combining this service. Independent community hospitals can consider having an interdisciplinary team create and coordinate an annual event for families. Parents releasing balloons on such a day with a name attached or lighting their candle amongst the group of candles have found solace in these events.

Creation of debriefing plan for staff members

Whether the staff have been providing pregnancy loss support for many years or bereavement services are an entirely new program, there will be patients whose losses affect the staff deeply. Nurses may also be involved in the death of the mother along with the fetus, or the complex situation of when the woman has been declared dead and the fetus is still alive (47). Whether a loss is expected or unexpected, at the beginning or pregnancy or late in gestation, involves other family members or solely the pregnancy, the staff may need to call for help. OR schedules, busy labor and delivery units, ongoing admissions to the NICU, the hectic ED or fast turnover clinics often do not allow the staff time to process these events. To elevate the standard of care for patients, support must be given to their providers. A plan should be in place that provides near immediate access to a chaplain, palliative care team member, ethics committee member or employee assistance counselor. Maloney (48) describes debriefing after an infant death that is universally applicable.

Conclusions

An integrated system of care increases quality and safety and contributes to patient satisfaction. Physicians, nurses and administrators must encourage pregnancy loss support so that regardless of where in the facility the contact is made, when in the pregnancy the loss occurs, or whatever the conditions contributing to the pregnancy ending, trained caregivers are there to provide bereavement support for the family and palliative symptom management to the fetus born with a life limiting condition. The goal for respectful caregiving throughout an entire hospital system is achievable. Bereavement initiatives throughout the healthcare system are critically important.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Margaret Campbell for including perinatal bereavement in this issue.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Cĵté-Arsenault D, Dombeck M. Maternal assignment of fetal personhood to a previous pregnancy loss: relationship to anxiety in the current pregnancy. Health Care Women Int 2001;22:649-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Frequently asked questions 090, Early Pregnancy Loss. August 2015 [cited 2018 Aug 25]. Available online: https://www.acog.org/Patients/FAQs/Early-Pregnancy-Loss

- Barfield WD. Standard terminology for fetal, infant, and perinatal deaths. Pediatrics 2016;137:e20160551. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- MacDorman MF, Gregory EC. Fetal and perinatal mortality: United States, 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2015;64:1-24. [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families; Field MJ, Behrman RE. editors. When children die: Improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2003.

- Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Committee on Hospital Care. Pediatric palliative care and hospice care commitments, guidelines, and recommendations. Pediatrics 2013;132:966-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wool C, Kain VJ, Mendes J, et al. Quality predictors of parental satisfaction after birth of infants with life‐limiting conditions. Acta Paediatrica 2018;107:276-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Resolve Through Sharing, Gundersen Medical Foundation, Inc. [cited 2018 Aug 25]. Available online: http://www.gundersenhealth.org/resolve-through-sharing/bereavement-training/

- Pregnancy Loss and Infant Death Alliance [cited 2018 Aug 25]. Available online: https://plida.org/

- Caring Cradle Creating Moments for Memories. [cited 2018 Aug 25]. Available online: https://caringcradle.com

- Limbo R, Lathrop A. Caregiving in mothers' narratives of perinatal hospice. Illness, Crisis Loss 2014;22:43-65. [Crossref]

- Blood C, Cacciatore J. Best practice in bereavement photography after perinatal death: qualitative analysis with 104 parents. BMC Psychol 2014;2:15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep. [cited 2018 Aug 25]. Available online: https://www.nowilaymedowntosleep.org/

- Wool C. State of the science on perinatal palliative care. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2013;42:372-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- English NK, Hessler KL. Prenatal birth planning for families of the imperiled newborn. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2013;42:390-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruiz Ziegler T. Perinatal Palliative Care, on YouTube. [cited 2018 Aug 25]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tY7mq1g9pGk

- Wool C, Côté-Arsenault D, Perry Black B, et al. Provision of services in perinatal palliative care: a multicenter survey in the United States. J Palliat Med 2016;19:279-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Denney-Koelsch E, Black BP, Côté-Arsenault D, et al. A survey of perinatal palliative care programs in the United States: Structure, processes, and outcomes. J Palliat Med 2016;19:1080-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Obeidat HM, Bond EA, Callister LC. The parental experience of having an infant in the newborn intensive care unit. J Perinat Educ 2009;18:23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dyer KA. Identifying, understanding, and working with grieving parents in the NICU, part I: Identifying and understanding loss and the grief response. Neonatal Network 2005;24:35-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gans D, Kominski GF, Roby DH, et al. Better outcomes, lower costs: palliative care program reduces stress, costs of care for children with life-threatening conditions. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res 2012;(PB2012-3):1-8.

- Kenner C, Press J, Ryan D. Recommendations for palliative and bereavement care in the NICU: a family-centered integrative approach. J Perinatol 2015;35:S19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Catlin A, Carter B. Creation of a neonatal end-of-life palliative care protocol. J Perinatol 2002;22:184-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Standards of Practice for Pediatric Palliative Care and Hospice. National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, Alexandria, VA: December 2012. [cited 2018 Aug 25] Available online: https://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/ChiPPS/Continuum_Briefing.pdf

- Choosing Thomas; A Family’s Desire to See their Child Live, If Only for a Brief Time. Dallas Morning News. [cited 2018 Aug 25]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ToNWquoXqJI

- Walter MA, Alvarado MS. Clinical aspects of miscarriage. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2018;43:E1-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reid M, McDowell J, Hoskins R. Communicating news of a patient's death to relatives. Br J Nurs 2011;20:737-40, 742. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Greiner AL, Conklin J. Breaking bad news to a pregnant woman with a fetal abnormality on ultrasound. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2015;70:39-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simpson R, Bor R. 'I'm not picking up a heart-beat': Experiences of sonographers giving bad news to women during ultrasound scans. Br J Med Psychol 2001;74:255-72. [Crossref]

- Kazak AE, Kassam-Adams N, Schneider S, et al. An integrative model of pediatric medical traumatic stress. J Pediatr Psychol 2006;31:343-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Catlin A. Interdisciplinary guidelines for care of women presenting to the emergency department with pregnancy loss. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2018;43:13-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- MacWilliams K, Hughes J, Aston M, et al. Understanding the experience of miscarriage in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs 2016;42:504-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Renker PR. Keep a blank face. I need to tell you what has been happening to me. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2002;27:109-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Catlin A. Pregnancy loss, bereavement, and conscientious objection in the perioperative services. J Perianesth Nurs 2018;33:553-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Catlin A. Doing the Right Thing by Incorporating Evidence and Professional Goals in the Ethics Consult. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2013;42:478-84; quiz E65-6.

- Berger JT. Moral Distress in Medical Education and Training. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:395-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wocial L, Ackerman V, Leland B, et al. Pediatric Ethics and Communication Excellence (PEACE) Rounds: Decreasing Moral Distress and Patient Length of Stay in the PICU. HEC Forum 2017;29:75-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chichester ML, Allston, S. Perinatal Loss Chaplain Utilization: What Nurses Request and What Patients Actually Need. Presented, Sigma Theta Tau, October 29, 2017.

- Jeuland J, Fitchett G, Schulman-Green D, et al. Chaplains Working in Palliative Care: Who They Are and What They Do. J Palliat Med 2017;20:502-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh P, Stewart K, Moses S. Pastoral Care following Pregnancy Loss: The Role of Ritual. J Pastoral Care Counsel 2004;58:41-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dickinson GE. A. 40-Year History of End-of-Life Offerings in US Medical Schools: 1975-2015. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2017;34:559-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verberne LM, Kars MC, Schepers SA, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a paediatric palliative care team. BMC Palliative Care 2018;17:23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carter BS, Levetown M, Friebert SE. Palliative Care for Infants, Children, and Adolescents: A Practical Handbook second edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011.

- Hall SL, Cross J, Selix NW, et al. Recommendations for enhancing psychosocial support of NICU parents through staff education and support. J Perinatol 2015;35 Suppl 1:S29-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. End of Life Nursing Curricula. Available online: http://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC/About/ELNEC-Curricula

- Levang E, Limbo R, Ziegler TR. Respectful Disposition After Miscarriage: Clinical Practice Recommendations. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2018;43:19-25. [PubMed]

- Catlin AJ, Volat D. When the fetus is alive but the mother is not: critical care somatic support as an accepted model of care in the twenty-first century? Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am 2009;21:267-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maloney C. Critical incident stress debriefing and pediatric nurses: an approach to support the work environment and mitigate negative consequences. Pediatr Nurs 2012;38:110-3. [PubMed]