Pediatric palliative care nursing

At least 400,000 children are living with life-threatening conditions each day in the United States, and approximately 53,000 children die each year (1). Palliative care is patient- and family-centered care that enhances quality of life throughout the illness trajectory (2) and can ease the symptoms, discomfort, and stress for children living with life-threatening conditions and their families (3). Key components of pediatric palliative care include physical, psychosocial, and spiritual dimensions, as well as decision-making guidance to families (4). Palliative care can coexist with treatment and is important from diagnosis, throughout a child’s illness, and beyond. Nurses are in ideal roles to provide pediatric palliative care at the bedside because they spend the most time with children and their families. This paper aims to help guide nurses and other healthcare providers in enhancing life and decreasing suffering for these children and their families by describing selected components of pediatric palliative nursing care based on recent literature and authors’ ongoing research. Topics were selected based on identified gaps in the pediatric palliative care literature including (I) nursing interventions; (II) international studies; (III) recruitment methods; (IV) communication; (V) training; (VI) nursing education; and (VII) nurses’ role in supporting the community.

Pediatric palliative care nursing interventions

Nursing intervention studies in pediatric palliative care are beginning to emerge as the state of the science gains momentum and researchers seek to learn new ways to assist children and their families dealing with life-limiting or life-threatening conditions. The authors’ recent work focusing on legacy and animal-assisted interventions are summarized below.

Legacy interventions

Legacy-making is defined as actions or behaviors aimed at being remembered and can improve coping and adjustment during illness and end of life for patients and their families (5-9). Leaving a legacy is a concern of seriously-ill children who understand that death is permanent and irreversible, and who are likely to think about death even if they do not communicate it explicitly (9). For children whose deaths can be anticipated, efforts to create memories and confirm they are loved and will be remembered are important (10). Children preparing for potential death may worry about being forgotten or have concern for loved ones that they will leave behind (11-13). In the terminal phase of an illness, children may wish to attend to unfinished business, such as delegating who will receive certain belongings after their death, writing letters, drawing pictures, taking a special trip, or speaking with significant people (14). Hospital staff have reported that legacy-making activities have helped ill children cope and communicate and helped family members cope, communicate, and continue bonds in the case of the child’s death (8). While legacy interventions have been shown to benefit adults with terminal illnesses and their family members (6), empirically-based legacy interventions had not been developed or tested in children.

Thus, we developed a legacy intervention via digital storytelling based on suggestions from children ages 7–17 years (n=8) with poor prognosis cancer and their parent caregivers (5). The intervention focuses on children’s personal characteristics (e.g., name, gender, appearance, personal traits), the activities that they like to do (e.g., hobbies, interests), and their connectedness with others (e.g., telling family members how much they are loved). After first testing our legacy intervention in a face-to-face format (requiring interviewing with an in-person videographer) in a sample of 28 children with advanced cancer and their parents (15), we expanded to our current study that is testing a web-based format to be more cost effective and allow greater access to participants. Our electronic intervention is a mobile-friendly web program that guides participants to create digital storyboards about themselves by directing them to: (I) answer legacy-making questions about themselves; (II) upload photographs; (III) upload videos; and (IV) upload music. Legacy interventions for children are showing strong promise to improve child and parent caregiver coping and adjustment outcomes, but more research is needed to determine meaningful aspects of intervention content, effects of legacy interventions, best timing to offer legacy services, and what children and families are most likely to benefit.

Animal-assisted interventions

The human-animal bond continues to be a phenomenon of interest in healthcare with animal-assisted interventions often viewed as a complementary alternative medical treatment to medications. Animal-assisted interventions can affect ways children experience symptoms, reducing their distress and improving quality of life (16,17). These interventions may occur with pets, therapy animals, or service animals. The American Pet Products Association conducts a biennial study (18) and found that 68% of American households have pets. Researchers determined pet ownership decreases depression and improves social adjustment, fitness, and weight status in children (17,19-21). Hospitalized children are usually not able to interact with their pets on a regular basis and animal-assisted interventions with handler/canine teams may play a key role in reducing anxiety and stress in children requiring care in a hospital or hospice.

Animal-assisted interventions may benefit many special populations, especially children with life-threatening conditions. As children and their parents navigate the challenging journey of dealing with life-threatening conditions, one potential strategy to decrease suffering of children with advanced disease is the use of animal-assisted interventions. The need for innovative, compassionate care that enhances quality of life for children and their families is a continuous concern as life-threatening conditions affect families in profound ways. They must cope with numerous physical concerns, as well as behavioral and psychosocial issues such as depression, anxiety, loneliness and relational strain. Adjunctive interventions can help an entire family cope with these concerns, and animal-assisted interventions are beginning to emerge in children’s hospitals across the United States. In the current healthcare environment, concerns about cost-containment and access to care are prevalent. Animal-assisted interventions with registered canines can be provided as a volunteer service, resulting in low cost and numerous benefits. According to children and their parents, time with a dog during clinic visits or hospitalization has resulted in (I) increased compliance and a willingness to actively participate in treatment; (II) distraction from pain and concerns about treatment outcomes; (III) decreased anxiety and perceptions of stress; (IV) unconditional acceptance; and (V) improved interactions with the healthcare team (16,17,22,23). These benefits differ for children of different ages, genders, development, and progression in their illness trajectory. Through normalizing a complex and sometimes daunting environment, canines may play a key role through the human-animal bond, their unconditional love thereby enhancing child and family well-being.

International studies

The World Health Organization (WHO) maintains statistics on worldwide mortality and morbidity. Startling data reveal that in 2015, 4.5 million infants died within the first year of life and sixteen thousand children died every day. Prematurity was the largest single cause of death. In various cultures in different parts of the globe, care must be taken to ensure knowledge and understanding of basic tenets and traditions surrounding life-threatening conditions and end-of-life (EOL) care. Even within the same country, diverse ethnic groups with a variety of values, principles and beliefs coexist, and it is incumbent on nurses and other healthcare providers to explore and honor those differences.

A seminal international study focusing on communication challenges when families are faced with having a child who is terminally ill was completed in Sweden (24), and findings may be useful to various cultures. All parents who experienced the death of their child between 1992 and 1997 were asked to complete a questionnaire, focusing on whether or not they talked about death with their child. Out of 449 parents who responded, none of the 147 who talked with their child about death regretted it, while 69 of the 258 parents who did not talk with their child about death regretted not doing so. Even though the study was completed well over a decade ago, its applicability may still resonate today in pediatric palliative care.

Authors’ examples of international palliative care studies include (I) parent-sibling bereavement after death of a child from cancer; (II) continuing bonds reported by bereaved individuals in Ecuador; and (III) circumstances surrounding deaths from the perspective of bereaved Honduran families.

Parent-sibling bereavement

This study compared multiple perspectives of changes in parents after a child’s death through interviews with bereaved parents and siblings in the US and Canada (25). Siblings and parents described major categories of change in their personal lives (e.g., emotions, perspectives and priorities, physical state, work habits, coping/behaviors, spiritual beliefs, and feeling something is missing) and relationships (e.g., family, others). Ninety-four percent of mothers, 87% of fathers, and 69% of siblings reported parental changes in at least one of these categories. Changes in priorities was more likely to be reported by parents and sadness was more likely to be reported by siblings.

Continuing bonds in Ecuador

A qualitative study explored how bereaved individuals in Ecuador described continuing bonds and found that 98% of participants reported having purposeful bonds such as keeping belongings or photos or visiting the cemetery (26). Sixty-one percent reported non-purposeful bonds like dreams. For participants in the study, the bonds were sometimes comforting (71%) and sometimes discomforting (55%). This research is another example of the need to provide culturally sensitive care to bereaved children and families.

Circumstances surrounding deaths in Honduras

Another qualitative study explored perceptions of bereaved individuals living in Honduras of circumstances surrounding the death of loved ones (27). Semi-structured interviews were later translated and transcribed. Sixty percent of participants were with other family members during their loved one’s EOL and 22.5% coped using spirituality or religious practices and connected with God. Participants expressed both comforting and discomforting continuing bonds when remembering the deceased. Results confirm a need to learn more about coping strategies and support mechanisms health professionals can use or suggest when working with bereaved in various cultures

Recruitment methods

Pediatric palliative care nursing research has spearheaded innovative research methods to address research challenges. For example, rigor of pediatric palliative care research is often challenged with small sample sizes, minimal sample diversity, and recruitment difficulties. Facebook ads have successfully recruited a variety of cohorts including populations of gays and lesbians, cigarette users, women with low income, college students, and adults who are depressed (28-34). While most studies have targeted adult age groups, Facebook ads have been used to recruit teenage and young adult populations such as Australian (ages 16–25) and Canadian (ages 15–24) youth affected by violence (35,36). With Facebook’s 1,110,000,000 active monthly users, 680,000,000 mobile users, and availability in 70 languages (37), Facebook advertising is a cost- and time-efficient strategy to recruit larger and more diverse samples within pediatric palliative care. To our knowledge, our pediatric palliative care nursing research studies are the first to have successfully used social media to recruit children receiving palliative care and their parent caregivers for research participation (38). More work is needed to determine how social media can best be used in pediatric palliative care research and clinical practice to improve care to children living with life-threatening conditions. Nursing researchers and clinicians are in ideal roles to lead out in innovative thinking and pioneering strategies to address unique challenges in pediatric palliative care.

Communication

Another priority area in pediatric palliative care where nurses can take the lead is related to communication. While essential to trusted relationships, effective communication among children with life-threatening conditions, parents, and the healthcare team often is poorly understood and executed. Disjointed, halted, or non-existent conversations can lead to anxiety, fear, and stress (11,39-41). This confusing or incomplete communication may be distressing to both providers and the families in their care. Providers generally desire open conversations about a child’s diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis but may find they lack resources or experience to facilitate these challenging discussions. Thus, healthcare providers are often hesitant to initiate early palliative care discussions with parents due to barriers such as insufficient time, cost, uncertainty of prognosis, perceived medical failure, fear of diminishing patients’ hope, and discomfort to initiate and engage in palliative care discussions (42-44). Specifically, nurses are often reluctant to discuss prognosis and palliative care options with families because often they are unsure what information may have been discussed by physicians and are also concerned about taking away patients’ hope (45). Still, providers are ethically responsible to provide patients and family members with information about prognosis and early palliative care options early after diagnosis and during illness (46,47). Although organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and WHO have noted the significance of early pediatric palliative care discussions (48,49), research evaluating the impact of early discussions has been very limited (50,51).

A gap exists in prospective evidence to evaluate parental preferences to receive palliative care and advanced care planning information during the early diagnosis period of children with poor prognosis types of cancer (50,51). In one seminal study (52), bereaved parents of 48 children that had died of cancer shared that: (I) more than 1/3 (36%) did not recall having any discussion about EOL with their providers; (II) 50% of the children received cancer-directed therapy at EOL, which parents viewed negatively in retrospect; and (III) although 48% of children died at home, 88% of these parents would have preferred home as the location of death in hindsight. Parents may be reticent to engage in candid discussions with a fear that open conversations about prognoses and timelines may reflect abandoned hope for cure (24,41,53,54). Parents may be in denial or afraid to acknowledge the possibility of their child’s death. In stifling the conversations, well-meaning parents hope to allay fear and depression in their children. These same parents may also decline valuable services offered through pediatric palliative care, such as advanced care planning. Additionally, pediatric providers commonly hold the fear that engaging in palliative care/EOL discussions with parents may take away their hope (55,56) and increase parents’ emotional distress (47). However, in reality, children who engage in open discussions about their prognosis and are given adequate time to process their status exhibit greater resilience than children who do not engage in candid conversations (57). Honest, empathetic, age-appropriate communication can decrease anxiety and fear of the unknown.

Training in pediatric palliative care

Currently, most practicing physicians, nurses, and other healthcare providers have not received training to engage in pediatric palliative care discussions with patients and families (56). The lack of interprofessional training among providers may contribute to the exclusion of nurses being present when physicians engage in discussions with families about the patient’s diagnosis and prognosis (58). In contrast, research has shown that parental hope significantly increased when pediatric providers offered poor prognosis information and early pediatric palliative care discussions (51,59). Research has suggested that physician communication training enhances their use of empathic communication (60), and collaboration of physicians and nurses during palliative care discussions has been associated with improved parent satisfaction with provider communication (51).

Helpful guides for communication are available to patients, their families, and providers. The guidelines acknowledge the importance of trusted relationships and the need to take care in considering best ways to listen to one another and share information and feelings. In fact, experts in pediatric palliative care are adamant the three most important procedures in pediatric palliative care are (I) listen, (II) listen, and (III) listen. The Conversation Project was developed to help people talk about their wishes for EOL care (61). The Conversation Starter Kit is useful in helping individuals have conversations with family members or loved ones about their goals and wishes at the end of life. The Pediatric Starter Kit is designed to help parents of seriously ill children who want guidance about having the conversation with their children.

Similar to patient guides, suggestions for best practice in pediatric palliative care communication are useful to inexperienced providers interested in strategies useful in connecting with families on a consistent basis while offering pediatric palliative care. The SPIKES 6-step protocol is used by many pediatric palliative care providers as it instills confidence to be straightforward and practical. The steps involve:

- S-SET up the conversation;

- P-Assess patient’s PERCEPTIONS;

- I-Obtain patient’s INVITATION;

- K-Give KNOWLEDGE and information to the patient;

- E-Address patient’s EMOTIONS with empathic response; and

- S-STRATEGIZE and SUMMARIZE.

Following these steps includes careful attention to non-verbal communication as well as spoken words. Additional guidelines for discussing EOL issues are outlined by Beale et al. (62). The authors stress that the most useful conversations occur long before a child is terminally ill and can be summarized by 6 Es:

- Establish an agreement with the family members and healthcare providers about open communication;

- Engage with the child at an opportune time, such as a new diagnosis, behavioral changes, or a change in prognosis;

- Explore what the child already knows and what she/he wants to know about the condition;

- Explain medical information according to developmental age and cognitive abilities;

- Empathize with the child’s reactions, allowing free expression of concerns;

- Encourage a child through your presence, but not reassurance that “everything will be fine”.

Training pediatric nurses and healthcare providers is necessary because there are not enough pediatric palliative care specialists available to meet the palliative care needs of children with life-threatening conditions and their families (63). This healthcare gap necessitates training of pediatric healthcare providers, including nurses, to deliver pediatric palliative care. Basic palliative care communication skills can be something that primary care teams (e.g., physician and nurse dyad) can provide (63). Additional benefits to having the primary team deliver pediatric palliative care and communication to families include continuity of care, an ongoing relationship with their primary team, and potentially better outcomes (64). For example, active oncologist involvement at the end of life for a child has been reported as important to parents and associated with decreased child pain and suffering (51,65). Research evaluating early pediatric palliative care communication interventions delivered by nurses and other healthcare providers are greatly needed.

Nursing education in pediatric palliative care

The complex nature of pediatric palliative care necessitates comprehensive ongoing educational opportunities for nurses working with children with life-threatening conditions and their families. Knowledge of evidence-based best practices is a key component of that education, but because of the nature of working with a vulnerable population, additional educational elements are essential to quality care. Expertise in communication does not necessarily come with advanced degrees and may need to be modeled and practiced by new nurses. Awareness of specific social and cultural traditions, beliefs, values is imperative to addressing child, family, and community needs. While providing palliative care, nurses must acknowledge their own feelings about human suffering, working with families in extremely difficult times, and the process of dying. Self-care is a crucial step in the educational process. Nurses must provide holistic care and address the physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs of children with life-threatening conditions and their families, focusing on the following concepts:

- Principles of palliative care;

- Goals of care;

- Cultural sensitivity;

- Quality improvement and evidence-based practice in palliative care;

- Interdisciplinary collaboration;

- Caring, compassion, humanity, humility, and altruism;

- Child’s concept of chronic illness;

- Legal and ethical issues;

- Family-focused care;

- Quality of life;

- Assessment and management of symptoms;

- Complementary and alternative medicine;

- Psychosocial care;

- Spiritual care;

- School and community issues;

- Child’s emotional and cognitive development;

- Child’s concept of death;

- Home care and hospice care;

- Advanced care planning such as do not resuscitate (DNR), allow natural death (AND);

- Communication of difficult news;

- Futility;

- Withholding or withdrawing of treatment;

- Death and dying;

- Grief and bereavement;

- Practical post-death issues (death certificates, morgue, medical examiner).

A wide variety of teaching methods are used in educating nurses about pediatric palliative care, including didactic sessions, supervised clinical practica, mentoring, role play of pre-determined sceneria, simulated/standardized patient encounters, computer-based modules and discussions, journal keeping, support groups, videos of family interactions, small group discussions, clinical case discussions, interdisciplinary encounters, and hospice and home visits.

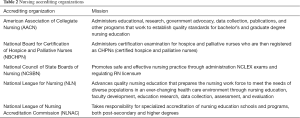

Agencies identified in Table 1 provide high quality resources to aid in nursing education focused on pediatric palliative care. Accreditation standards in nursing are determined and administered by a variety of agencies (Table 2). The standards function as a framework of self-evaluation and on-going curricular development in expanding topics of interest to the profession.

Full table

Full table

Nurses’ role in supporting the community

The emotional strains experienced by parents when making palliative and EOL care decisions when their child has a serious illness have been documented in the literature (66,67). Research has provided increasing evidence that many young and middle-aged adults are dealing with the stressors related to the chronic care of another family member (e.g., spouse or elderly parent) (68). Evidence has shown that 78% of Americans have no understanding of the difference between palliative care and hospice care (69).

Because of the expanded healthcare delivery brought about by the former president Barak Obama’s 2010 Patient Protection and the Affordable Care Act, more children and adolescents with complex and chronic conditions (CCC) and life-limiting conditions are more likely to be in need of healthcare in traditional health care settings (e.g., hospital and clinics), living in the community and attending school, and in need of healthcare providers who serve as advocates for their unique healthcare needs and preferences in a variety of community settings (e.g., elementary and high school settings) (70). Approximately 2,500 adolescents and 1,400 preadolescent children in the United States are within 6 months of dying from a CCC each day, and affected children are increasingly dying in the community and outside of medical setting (70). Additionally, the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 1997 and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 has provided policies that ensure children with health care needs will be accommodated and able to attend school (70). Therefore, school nurses are in a unique position to be responsible, not only for the healthcare needs of children with CCC, but to also assess and honor the preferences of children with complex healthcare needs attending school. For example, school-age and adolescent aged children life-limiting conditions may prefer to attend school without the risk of having resuscitation efforts attempted in the event they had a cardiopulmonary arrest event during school (71). Shockingly, evidence exists that (I) 80% of surveyed school districts do not have policies, regulations or protocols in place to deal with DNR orders or preferences by their students and their parents; and (II) 76% of the surveyed school districts would not honor student DNR wishes or were uncertain if they could honor specified DNR preferences by students and families (71). Therefore, parents of children with CCC attending community schools would especially benefit from receiving information about DNR and palliative care options and potential related benefits for children with CCC and life-limiting conditions. School nurses should receive DNR and pediatric palliative care training on their role and responsibilities to effectively advocate for children with serious illnesses, their parents, and teachers and provide them with accurate and timely information (72). Recognizing school nurses’ roles and opportunities and appropriately equipping them could assist school nurses to empower parents to consider pediatric palliative care prior to having a child with a serious or life-threatening condition.

Conclusions

Certainly, nurses play a significant role in caring for children living with, suffering from, and dying of life-threatening conditions. More research is needed to continue advancing the science of pediatric palliative nursing care, to further improve our understanding for how to enhance life and decrease suffering for these vulnerable children and their families who are high risk for negative consequences. In general, the field is ready to move from descriptive to intervention work and expand research populations to include non-cancer diagnoses. Nursing researchers must step up and pave the way to develop and carry out rigorous interdisciplinary studies to further advance the science of pediatric palliative care. Taking advantage of funding opportunities (e.g., National Institute of Nursing Research funding for palliative care and EOL research), seeking leadership roles within national palliative care organizations (e.g., Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association), and mentoring students and junior scientists to build the next generation are examples of roles that pediatric palliative care nurse researchers must fill. More attention to better equipping nurses at the bedside and other healthcare professionals in pediatric palliative care is essential to providing the best clinical care to children and their families and supporting the community at large. Finally, nurses are in ideal positions to bridge potential gaps between providers across disciplines, children and their family members, researchers and clinicians, students and mentors, communities and politicians so that we are all working together in one accord to improve life for children living with life-threatening conditions and their families.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This paper includes work supported by funding from the National Institute of Nursing Research (1R01NR015353 to TF Akard); American Cancer Society (IRG-58-009-54 to TF Akard); Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (68045 to TF Akard); Zoetis Animal Health (to MJ Gilmer); National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences/National Institutes of Health (UL1 TR000445); and support from the Palliative Care Research Cooperative funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (U24NR014637).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO). 2017. Available online: https://www.nhpco.org/quality/nhpco’s-standards-pediatric-care

- National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care (3rd ed.). 2013. Available online: https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/NCP_Clinical_Practice_Guidelines_3rd_Edition.pdf

- National Institute of Nursing Research. Palliative Care: Conversations Matter. 2015. Available online: https://www.ninr.nih.gov/newsandinformation/conversationsmatter/conversations-matter-newportal

- National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO). NHPCO’s Facts and Figures: Pediatric Palliative & Hospice Care in America, 2015 Edition. 2015. Available online: https://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/quality/Pediatric_Facts-Figures.pdf

- Akard TF, Gilmer MJ, Friedman DL, et al. From qualitative work to intervention development in pediatric oncology palliative care research. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2013;30:153-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard T, et al. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:5520-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coyle N. The hard work of living in the face of death. J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;32:266-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Foster TL, Dietrich MS, Friedman DL, et al. National survey of children's hospitals on legacy-making activities. J Palliat Med 2012;15:573-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Foster TL, Gilmer MJ, Davies B, et al. Bereaved parents' and siblings' reports of legacies created by children with cancer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2009;26:369-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Levetown M, Liben S, Audet M. Palliative care in the pediatric intensive care unit. In: Carter BS, Levetown M. editors. Palliative Care for Infants, Children, and Adolescents: A Practical Handbook. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004:275-93.

- Hinds PS, Schum L, Baker JN, et al. Key factors affecting dying children and their families. J Palliat Med 2005;8 Suppl 1:S70-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lanctot D, Morrison W, Koch K. Spiritual dimensions. In: Carter BS, Levetown M, Friebert SE. editors. Palliative Care for Infants, Children, and Adolescents: A Practical Handbook 2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Press, 2011:227-43.

- McSherry M, Kehoe K, Carroll JM, et al. Psychosocial and spiritual needs of children living with a life-limiting illness. Pediatr Clin North Am 2007;54:609-29. ix-x. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armstrong-Dailey A, Zarbock S. Hospice Care for Children. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Akard TF, Dietrich MS, Friedman DL, et al. Digital storytelling: an innovative legacy-making intervention for children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62:658-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goddard AT, Gilmer MJ. The role and impact of animals with pediatric patients. Pediatr Nurs 2015;41:65-71. [PubMed]

- Urbanski BL, Lazenby M. Distress among hospitalized pediatric cancer patients modified by pet-therapy intervention to improve quality of life. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2012;29:272-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Pet Products Association. APPA National Pet Owners Survey 2017-2018. 2017. Accessed November 14, 2017. Available online: http://americanpetproducts.org/Uploads/MemServices/GPE2017_NPOS_Seminar.pdf

- Lem M, Coe JB, Haley DB, et al. The protective association between pet ownership and depression among street-involved youth: a cross-sectional study. Anthrozoös 2016;29:123-36. [Crossref]

- Ward A, Arola N, Bohnert A, et al. Social-emotional adjustment and pet ownership among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. J Commun Disord 2017;65:35-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Westgarth C, Boddy LM, Stratton G, et al. The association between dog ownership or dog walking and fitness or weight status in childhood. Pediatr Obes 2017;12:e51-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilmer MJ, Baudino MN, Tielsch Goddard A, et al. Animal-assisted therapy in pediatric palliative care. Nurs Clin North Am 2016;51:381-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wells DL. The effects of animals on human health and well-being. J Soc Issues 2009;65:523-43. [Crossref]

- Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Onelov E, et al. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1175-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gilmer MJ, Foster TL, Vannatta K, et al. Changes in parents after the death of a child from cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;44:572-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Foster TL, Roth M, Contreras R, et al. Continuing bonds reported by bereaved individuals in Ecuador. Bereave Care 2012;31:120-8. [Crossref]

- Stone A, LaMotta CP, Baudino MN, et al. Circumstances surrounding deaths from the perspective of bereaved Honduran families. Int J Palliat Nurs 2016;22:82-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cavallo DN, Tate DF, Ries AV, et al. A social media-based physical activity intervention: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 2012;43:527-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaysen D, Davis KC, Kilmer J. Use of social networking sites to sample lesbian and bisexual women. The Addictions Newsletter 2011;18:14-5.

- Lohse B. Facebook is an effective strategy to recruit low-income women to online nutrition education. J Nutr Educ Behav 2013;45:69-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell JW, Petroll AE. Patterns of HIV and sexually transmitted infection testing among men who have sex with men couples in the United States. Sex Transm Dis 2012;39:871-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morgan AJ, Jorm AF, Mackinnon AJ. Internet-based recruitment to a depression prevention intervention: lessons from the Mood Memos study. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Popenko NA, Devcic Z, Karimi K, et al. The virtual focus group: a modern methodology for facial attractiveness rating. Plast Reconstr Surg 2012;130:455-61e. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramo DE, Prochaska JJ. Broad reach and targeted recruitment using Facebook for an online survey of young adult substance use. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chu JL, Snider CE. Use of a social networking web site for recruiting Canadian youth for medical research. J Adolesc Health 2013;52:792-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fenner Y, Garland SM, Moore EE, et al. Web-based recruiting for health research using a social networking site: an exploratory study. J Med Internet Res 2012;14:e20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brain Statistics. Facebook Statistics 2017. Accessed August 17, 2017. Available online: http://www.statisticbrain.com/facebook-statistics/

- Foster Akard T, Gerhardt CA, Hendricks-Ferguson V, et al. Facebook advertising to recruit pediatric populations. J Palliat Med 2016;19:692-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hilden J, Himelstein BP, Freyer DR, et al. Improving Palliative Care for Cancer. 2001. Available online: https://www.nap.edu/read/10149/chapter/8#183

- Jalmsell L, Lovgren M, Kreicbergs U, et al. Children with cancer share their views: tell the truth but leave room for hope. Acta Paediatr 2016;105:1094-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Geest IM, van den Heuvel-Eibrink MM, van Vliet LM, et al. Talking about death with children with incurable cancer: perspectives from parents. J Pediatr 2015;167:1320-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gysels M, Richardson A, Higginson IJ. Communication training for health professionals who care for patients with cancer: a systematic review of effectiveness. Support Care Cancer 2004;12:692-700. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Visser M, Deliens L, Houttekier D. Physician-related barriers to communication and patient- and family-centred decision-making towards the end of life in intensive care: a systematic review. Critical Care 2014;18:604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weaver MS, Heinze KE, Kelly KP, et al. Palliative care as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015;62:S829-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Helft PR, Chamness A, Terry C, et al. Oncology nurses' attitudes toward prognosis-related communication: a pilot mailed survey of oncology nursing society members. Oncol Nurs Forum 2011;38:468-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Karnik S, Kanekar A. Ethical issues surrounding end-of-life care: a narrative review. Healthcare (Basel) 2016;4:E24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mack JW, Joffe S. Communicating about prognosis: ethical responsibilities of pediatricians and parents. Pediatrics 2014;133:S24-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics 2000;106:351-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Cancer Control: Palliative Care. WHO Guide for Effective Programmes. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2007.

- de Vos MA, Bos AP, Plötz FB, et al. Talking with parents about end-of-life decisions for their children. Pediatrics 2015;135:e465-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hendricks-Ferguson VL, Pradhan K, Shih CS, et al. Pilot evaluation of a palliative and end-of-life communication intervention for parents of children with a brain tumor. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2017;34:203-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hechler T, Blankenburg M, Friedrichsdorf SJ, et al. Parents' perspective on symptoms, quality of life, characteristics of death and end-of-life decisions for children dying from cancer. Klin Padiatr 2008;220:166-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg AR, Wolfe J, Wiener L, et al. Ethics, emotions, and the skills of talking about progressing disease with terminally ill adolescents: a review. JAMA Pediatr 2016;170:1216-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Perceptions of palliative care among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. CMAJ 2016;188:E217-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Almack K, Cox K, Moghaddam N, et al. After you: conversations between patients and healthcare professionals in planning for end of life care. BMC Palliat Care 2012;11:15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Granek L, Krzyzanowska MK, Tozer R, et al. Oncologists' strategies and barriers to effective communication about the end of life. J Oncol Pract 2013;9:e129-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wiener L, Weaver MS, Bell CJ, et al. Threading the cloak: palliative care education for care providers of adolescents and young adults with cancer. Clin Oncol Adolesc Young Adults 2015;5:1-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hebert K, Moore H, Rooney J. The nurse advocate in end-of-life care. Ochsner J 2011;11:325-9. [PubMed]

- Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, et al. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:5636-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, et al. Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer-based training program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:593-601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- The Conversation Project. Accessed November 15, 2017. Available online: http://theconversationproject.org/

- Beale EA, Baile WF, Aaron J. Silence is not golden: communicating with children dying from cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:3629-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Comprehensive Cancer Care for Children and Their Families: Summary of a Joint Workshop by the Institute of Medicine and the American Cancer Society. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2015.

- Steele AC, Kaal J, Thompson AL, et al. Bereaved parents and siblings offer advice to health care providers and researchers. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013;35:253-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med 2000;342:326-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carroll KW, Mollen CJ, Aldridge S, et al. Influences on decision making identified by parents of children receiving pediatric palliative care. AJOB Prim Res 2012;3:1-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Feudtner C, Carroll KW, Hexem KR, et al. Parental hopeful patterns of thinking, emotions, and pediatric palliative care decision making: a prospective cohort study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:831-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013.CD007760. [PubMed]

- Center to Advance Palliative Care. 2011 Public Opinion Research on Palliative Care. 2011. Available online: https://media.capc.org/filer_public/18/ab/18ab708c-f835-4380-921d-fbf729702e36/2011-public-opinion-research-on-palliative-care.pdf

- Council on School Health and Committee on Bioethics. Murray RD, Antommaria AH. AAP Policy Statement: Honoring do-not-attempt-resuscitation requests in schools. Pediatrics 2010;125:1073-7. [Crossref]

- Kimberly MB, Forte AL, Carroll JM, et al. Pediatric do-not-attempt-resuscitation orders and public schools: a national assessment of policies and laws. Am J Bioeth 2005;5:59-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Newell ME. Patients of the future: a survey of school nurse competencies with implications for nurse executives in the acute care settings. Nurs Adm Q 2013;37:254-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]