Improving patient outcomes through palliative care integration in other specialised health services: what we have learned so far and how can we improve?

Introduction

Although in the past palliative care has often been seen to be synonymous with care at the end of life there is increasing discussion about a more integrated approach to care, with early integration of palliative care, with the aim of improving patient outcomes. This review will consider the evidence that is available for this integrated approach, and how different approaches to integration have been developed, according to local circumstances but also related to the disease group considered.

Within the definition of palliative care by the World Health Organisation there is no restriction in the timing of the intervention or restriction to any diagnosis or to end of life, but the care relates to any person with a life threatening illness. This definition states that palliative care is “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering, early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psycho-social and spiritual” (1). However over the last 50 years as palliative care has developed there has been an emphasis on the care of people with cancer and towards the end of life—as shown in Western Australia where 68% of the people dying of cancer received specialist palliative care whereas only 8% of those dying of non-cancer conditions did so (2).

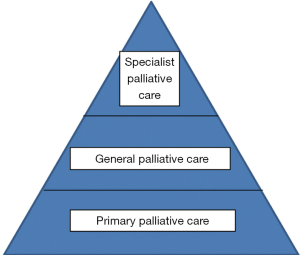

These views are now being challenged and there is an increasing pressure to have a palliative care approach from earlier after diagnosis and for an integrated approach with increased collaboration with other specialties to improve care, with an emphasis on the holistic care of patients and families. However there is often a confusion of terminology as to what is being considered to be palliative care and by whom it is provided (3). There is the duty of all professionals to provide a holistic approach and also the need for a more specialised service for people with complex needs. The interaction between all these needs and the providers can lead to confusion and difficulties for all concerned—patients, families and professionals. The European Association for Palliative Care has suggested that there are different ways of palliative care provision as shown in Box 1.

Within oncology, and increasingly in the care of other disease groups, the concept of “supportive care” has been suggested. This aims to optimize the comfort, function and social support of the patient and family at all stages of the illness (4). This has been suggested to not only include all disease related therapy but includes patient directed therapy and family directed therapy—including information, psychological support, rehabilitation, complementary therapies, pain management, social care, spiritual care, specialist palliative care and, as appropriate “life—maintaining therapies”, such as blood transfusion, ventilator support, hydration and feeding (5).

Thus how the care is provided may be complex with several different teams involved. The way services may be integrated within the existing specialist service is unclear and varies greatly. For instance within oncology different models have been suggested:

- Solo practice—where the oncologist provides palliative care, but due to time and experience this may be limited;

- Congress practice—with the oncologist referring to various specialities to manage the issues, although this may be fragmented;

- Integrated care—the oncologist routinely refers patients for palliative care, with active collaboration (6).

Whereas in neurological care there has been close integration with palliative care being part of the multidisciplinary team and involved with all patients and their families from the time of diagnosis. These different models may depend on the disease progression as well as the circumstances within the service—differences in attitude, team working and availability of care.

However the aim should be to improve the care for patients and their families and reduce symptom burden and maximize, or improve, quality of life. The approaches to integrated care will be considered for three areas in particular:

- Cancer—where the disease progression may vary greatly and there may be the options of treatment that may potentially cure or slow the disease progression;

- Progressive neurological disease—where there is likely to be disease progression, over a varying period of time;

- Heart failure—where there may be ambiguity of the prognosis as there is gradually diminishing functional status with periodic exacerbations of the illness (7).

These will be used an exemplars for the consideration of integrated care for other diseases, including those with a more sudden or more prolonged trajectory (7).

Cancer

Over many years there has been increasing discussion of the integration of palliative care within oncology services. However there is increasingly a disease orientated approach to cancer care as there have been now developments in treatment, but this does not always lead to an improved quality of care (8). Health care costs in the USA have increased relative to outcomes and the holistic approach, considering the wider aspects of care including psycho-social and spiritual, is often lost. However there have been several studies that have shown an improvement in patient outcomes when palliative care in included earlier in the disease progression and treatment.

In 2010 a study showed that early palliative care for patients with non-small cell lung cancer improved not only quality of life and mood, but led to a longer survival (9). Patients were randomised to standard care or early palliative care, when they were seen by a member of the palliative care team within 3 weeks and monthly as outpatients until death. One hundred and seven were fully assessed and the quality of life assessed by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Lung Scale and found to be higher 98 (scores 0–136) in the patient group who received palliative care compared to 91.5 in the control group (P=0.03). The proportion of patients with depression, as assessed on the HADS score was lower in the palliative care group—16% compared to 38% (P=0.01). The length of survival was 11.6 months in the palliative care group compared to 8.9 months (P=0.02) and this appeared to be primarily as the palliative care group received less aggressive care at the end of life—33% compared to 54% (P=0.05). Thus the involvement of palliative care would seem to help patients decide on treatment options and reduce the risk of a more aggressive approach at the end of life.

A further study with newly diagnosed patients with lung and gastro-intestinal cancers involved 350 people, again with a monthly consultation with palliative care (10). There was again an improvement of quality of life after 24 weeks. The lung cancer patients showed an improvement in quality of life and depression at 12 and 24 weeks, whereas the control group deteriorated. The patients with gastrointestinal cancers also improved at 12 weeks. Patients were also more likely to discuss their wishes if they were dying with the oncologist—30% compared to 14.5% (P=0.04). Caregivers were also assessed and showed improvement in total distress and depression at 12 weeks, but no change in quality of life or anxiety (11). These changes were not seen at 24 weeks, although the numbers were small. Thus these studies have shown that early palliative care intervention was helpful for both patient and caregiver.

Other studies have shown similar results. The ENABLE Trial used advanced practice nurses to lead educational sessions for patients combined with monthly group medical appointments. Quality of life improved and depression was lessened in the intervention group, although days in hospital, ICU or emergency department visits were unchanged (12). A further similar trial, ENABLE III, again offered a palliative care consultation, coaching sessions and monthly follow up for after enrolment or 3 months later (13). No changes were seen in symptoms or quality of life but the 1-year survival rates were 63% for the intervention and 48% in the control group (P=0.038). It is unclear what may have led to these differences but the median participation was 240 to 493 days, and during this time relationships may have been developed with the palliative care team, which may have influenced treatment decisions and reduced the more aggressive treatments, although these were not recorded. A study of the caregivers in ENABLE III showed that the early intervention favoured a reduction in depression and stress burden, but not quality of life or other burdens (14).

A further study in Canada involved 461 patients with cancer who were seen by a palliative care team within a month and then monthly whereas the control group were followed up within oncology (15). At 3 months there was some evidence of improvement in quality of life but by 4 months there were significant improvements in quality of life and symptoms. Patient satisfaction also improved.

In Italy, 207 patients were randomised to receive early palliative care consultation, followed by appointments very 2 to 3 weeks compared to standard oncological care with palliative care referral if requested (16). The early involvement of palliative care led to increased hospice care and admission to hospice and reduced chemotherapy in the last 30 days of life—18.7% compared to 27.8% (P=0.036). There were non-significant reductions in hospitalisation, emergency room visits and hospital deaths. Thus again there seem to be benefits of early involvement and reduced aggressive treatment at the end of life.

These papers do show the evidence that palliative care is helpful for patients with cancer. A systematic review of the effectiveness of specialist palliative care for terminally ill patients focussed on 22 trials (17). However only 13 had quality of life as an outcome, and only in four was this a specified primary outcome. Only four studies showed a significant difference in quality of life, although this lack of evidence may reflect the lack of power in the samples, recruitment, attrition, contamination of control groups, randomisation problems in cluster studies and difficulties in assessing and detecting differences in quality of life. Fourteen studies assessed symptom management but again only one showed a significant benefit for individual symptoms but others did show improvement in symptom distress (17). Satisfaction with care was found to improve in only two of the 10 studies looking at this area. Overall there was limited evidence, although this may have been due to the issues outline above (17).

A recent trial in Denmark has again showed no evidence for the effectiveness of palliative care, apart from in the management of nausea and vomiting (18). However no harmful effects of palliative care found and it was felt that the intervention may have been insufficient, as the palliative care team’s previous experience had been with advanced cancer and they may have perceived that the patients had few major issues and few contacts were made. Moreover there may have been increased care provided to the control group, either as the professionals compensated for the lack of palliative care by encouraging more medical contacts for the control participants or that the oncologists had become more experienced in palliative care and were providing better palliative care support (18).

Thus there does seem to be evidence that early palliative care is helpful for patients with advancing cancer and may help some symptoms, particularly depression, improve quality of life, reduce aggressive therapy at the end of life, caregivers, reduce hospitalizations, increase the use of advance directives and may reduce costs (8). However a review of the trials has shown that there are many methodological problems in these trials—of defining the “usual” care, when “early” applied, heterogeneity of populations, attrition, and a lack of an economic focus (8). This review suggested that new studies were necessary.

There is increased interest in providing palliative care—either as increased general palliative care within an oncological service or liaison and collaboration with specialist palliative care. As discussed above different models have been suggested:

- Solo practice—where the oncologist provides palliative care, but due to time and experience this may be limited;

- Congress practice—with the oncologist referring to various specialities to manage the issues, although this may be fragmented;

- Integrated care—the oncologist routinely refers patients for palliative care, with active collaboration (6).

These concepts have been further developed and it has been suggested that the requirements of care are to focus on the patient’s particular needs, in particular:

- Acute needs—such as pain control;

- Chronic needs can then be considered—such as fatigue/anxiety/advance care planning;

- Psychosocial issues may be assessed and helped by a wider interdisciplinary approach;

- Existential/spiritual issues may then be considered;

- There is a need for ongoing support to allow the relationships to be developed, that may then allow the discussion of these deeper issues. A single visit is insufficient to address all the issues (19).

Thus there are many models but often this is based on the assumption that a referral/involvement of specialist palliative care is necessary. However if patient care is to be improved there is a need for all services, including oncological services, to be able to provide general palliative care and be willing to refer for more specialist help if the issues are more complex. This referral to specialist services is often delayed, and the development of the term “supportive care” has aimed to help this (4,5), as palliative care a seen by many oncologists, and patients, as related to hospice and the end of life (20). Easier, and earlier, referral has been shown to help patient and families but a more holistic approach by all health and social care professionals would also help to improve care, at all stages of the disease progression.

The experience gained from the studies shows that there is a need to help oncologists see the holistic needs of patients and families and use their own teams to help and be willing to refer for palliative care support (20). The use of triggers to help in the referral has been suggested and regular screening of symptoms and other issues also enables all to be aware of issues that may need to be addressed (19). There is also the need for further education and training of oncologists, in training and in continuing education, and it has been suggested that oncologists could undertake accreditation in palliative medicine and be a resource within an oncology centre (19). There is also the need to ensure that resources are available to provide this extra support, although if less aggressive treatment is undertaken in the later stages of the disease and there is less hospitalization this support may be cost neutral (21).

The integration of palliative care within cancer services has been shown to be helpful and is continuing to be developed. This may be part of a wider medical, nursing and societal appreciation of the role of palliative care and will be discussed later.

Neurology

From the early days of St Christopher’s Hospice, London in 1967, the first of the new hospices providing palliative care in the UK, patients with progressive neurological disease were admitted, as recorded in letters from Dame Cicely Saunders (22). The role of palliative care has been continued for many disease groups, but in particular motor neurone disease/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MND/ALS). The holistic care, involving careful symptom management and psychosocial/spiritual support of patients and families, has been shown to improve care and minimise the risk of a distressing death (23).

Over recent years there has been increasing awareness of the need to extend this palliative care approach to all neurological diseases and in 2016 the European Association for Palliative Care and the European Academy of Neurology produced a Consensus paper on palliative care in neurology (24). This recommended that palliative care should be integrated from early in the disease progression, depending on the diagnosis—for MND/ALS, which has a short prognosis of a mean of 2–3 years, this may be from diagnosis, and in Parkinson’s disease (PD), with an average prognosis of 15 years this may be at a later stage (24). The use of triggers to help identify the deterioration and probable end of life was suggested (25). The triggers include swallowing problems, recurring infection, marked decline in functional status, first episode of aspiration pneumonia, cognitive difficulties, weight loss and significant complex symptoms (25) and could allow neurological services to consider that death may be foreseen in the coming months and allow referral and involvement of palliative care services. Initial research has shown that the triggers do increase as death approaches and may be helpful in this prognostication, and subsequent referral (26).

There is also increasing evidence that palliative care is helpful in improving the patient outcomes and quality of life for people with progressive neurological disease. Studies in London for patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) showed that showed there was an improvement in symptoms in the group receiving palliative care, whereas there was deterioration in the control group (27). Moreover there was an improvement of caregiver burden (27) and this care was shown to be cost effective (28). A study in Turin in Italy considered a broader group of neurological diseases—MND/ALS, MS, PD and Parkinson’s plus disorders—and showed that the involvement of the wider multidisciplinary palliative care team led to improvement in symptoms—pain, breathlessness, sleep disturbance and bowel symptoms—and quality of life, but no significant changes in caregiver burden (29). However an Italian study on short term input in MS showed the involvement of specialist nurses, who had received extra training in palliative care and support, did lead to a reduced symptom burden but had no effect on quality of life or other outcomes (30).

There is also increasing evidence of palliative care becoming integrated into the multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach within neurological teams. This increasing emphasis on the MDT approach within neurology has been emphasized by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for people with MND, where a MDT approach, including palliative care input, was recommended and found to be cost-effective (31). There are several studies showing that for people with MND/ALS that the involvement of a specialist MDT—professionals with experience of the care of that particular disease and working closely together, and often including palliative care—leads not only to a benefit in quality of life but an increased survival. A study from Sheffield showed a median survival of 19 months for those receiving MDT care, compared to 11 months for the group who had received regular neurology follow up only (32). A study from Ireland showed again a survival advantage of the specialised MDT approach with a median survival of 1.22 years for the MDT group compared to 0.98 years for the control group (33). Both of these studies are open to bias as they have used retrospective cohorts as a control (32) or a control group from a different area (33), but there does seem to be increasing evidence that the MDT team, which encompasses a holistic approach and provides general palliative care, is helpful in both quality and length of life.

Within stroke services the role of palliative care is more complex, as this is a sudden event and patients and families face an unexpected serious prognosis. An Australian study found that 50% of the patients who died in the stroke unit had been completely independent and well prior to the stroke (34). Guidelines stress the need for palliative care, particularly for patients who have a catastrophic stroke or who have pre-existing morbidity (35) and recommend that palliative care principles should be seen as a key component in stoke care. There were recommendations for the recognition the symptom issues that may occur, ensuring good communication with patients and families, particularly in prognostication and negotiating management plans, and stroke services would be expected to provide the majority of palliative and end of life care with support from specialist services if necessary (35,36). Creutzfeldt has suggested the use of a “Palliative care needs checklist”—considering:

- Does this patient have pain or distressing symptoms?

- Do the patient and/or family need social support or help with coping?

- Do we need to readdress goals of care or adjust treatment according to patient-centred goals?

- What needs to be done today? (36)

Thus the recognition of palliative care needs is essential and most patients can be assessed and managed by the stroke team, with consultation with specialist services when the issues are more complex—often with more complex decision making at end of life (34).

Within dementia care there has also been an increasing emphasis on ensuring patients receive appropriate palliative care. The EAPC White Paper reinforced this opinion, and a Delphi study of international experts rated the importance of palliative care at 8.3/10 and palliative care was felt to be important for all people with dementia and should not be restricted to those with severe dementia (37). There is the need for all professionals involved in the care to use the principles of palliative care throughout the patient’s disease progression. As the patient approaches end of life these issues may be more pronounced, ensuring that the patient is comfortable and avoiding over burdensome or futile treatments (37,38). As many patients with dementia will be within nursing or residential homes palliative care should be a major role within these institutions and palliative care skills developed for the professionals (38).

Thus there is some evidence that patient outcomes do seem to improve with early palliative care involvement, with improvements in symptoms, quality of life and maybe survival, although this evidence is from small studies and predominantly, but not exclusively, for MND/ALS. The evidence is not as well developed as in cancer but there are studies showing that there is a clear improvement in quality of life and symptom burden (27,29). The Consensus paper stressed the need for further education, of neurologists in palliative care and palliative care specialists in neurology, to enable the approach to develop further (24).

Heart failure

The role of palliative care for heart failure has increased over the last 10 years and in the Heart Failure Association/European Society of Cardiology Guidelines on the treatment of acute and chronic heart failure palliative care is suggested early in the disease progression, increasing as the disease progresses (39). The Guidelines also suggest ongoing discussion regarding the management plan and emotional/social/spiritual support (39).

There are studies showing that palliative care can help in the management of symptoms and the well-being of patients. The PREFER study in Sweden considered the effectiveness of a home based palliative care service compared to usual primary care (40). The results showed an improvement in quality of life, nausea, total symptom burden, self-efficacy and reduced hospitalizations (40). The care offered differed to many palliative care teams in as much as the PREFER team would also manage the heart failure and any other co-morbidities, in collaboration with the primary care team. This was important in improving symptoms, as active heart failure management was used in conjunction with palliative procedures and medication.

A study of an out-patient palliative care consultation, usually before discharge from hospital, in California showed improvement, at 3 months, for symptom burden, depression and quality of life (41). These patients were all symptomatic with the heart failure and this was a single consultation, when a management plan was drawn up in collaboration with the patient and family. A study in Hong Kong assessed patients at home, followed by ongoing support in person or by telephone (42). Although there was improvement in assessed quality of life, higher patient satisfaction and lower caregiver burden at 12 weeks, there was no difference in symptom distress or functional status (42).

In one study an embedded approach was assessed, where a clinical nurse specialist from palliative care met weekly with the cardiac team to identify eligible in-patients (43). After discharge from hospital a community based palliative care nurse practitioner provided 24/7 symptom management support with the involvement of other members of the multidisciplinary team, as necessary. The interventions led to an increase in advance care planning and high levels of patient and family satisfaction but no change in hospital visits or readmissions (43).

As there is great variability in the progression of heart failure the use of needs assessment has been suggested to help identify patients who may have palliative care needs. . The Needs Assessment Tool:Progressive Disease-Heart failure (NAT:PD-HF) was found to be easy to administer and was a potential way of identifying physical and psychosocial issues (44). The Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale (IPOS) has been shown to be feasible for use in ascertaining the issues important to the patient with heart failure (45) and was found to be acceptable and not burdensome to patients, allowing their views to be ascertained easily in clinical settings (45). These measures may be an easier way for the palliative care issues to be identified for this complex group of patients, allowing resources to be targeted appropriately and effectively.

Thus palliative care involvement in the care of heart failure patients was often by referral or involvement of specialist palliative care teams and the use of scales could help facilitate referral. However there are still major gaps in access to palliative care and a UK study showed that only 58% of palliative care teams reported collaboration with cardiology teams and this was often as ad hoc joint working (71%) rather than pre-planned MDT meetings (37%), working groups (21%) or mutual education (36%) (46).

There does seem to be evidence that palliative care involvement in the care of people with heart failure may improve symptoms, help with psychosocial issues, aid advance care planning and increases quality of life for patients and families. The approach has been often by referral to other services but an embedded approach, with regular interactions between the palliative care and cardiology teams seems to be very helpful.

Discussion

There is increasing, but limited, evidence that the involvement of palliative care earlier in the disease progression may lead to improvement in quality of life, symptom management, less aggressive treatment at the end of life and maybe survival as has been shown in the studies described above. However the evidence is varied and there are many issues within studies, relating to recruitment, retention, attrition of participants and the design of studies.

Two large systematic reviews have also considered the effective of palliative care on quality of life (47) and patient and carer outcomes (48) and showed small effects on quality of life. A meta-analysis of 43 trials, involving 12,371 patients, found a statistically and clinically significant improvement of quality of life, although this effect was lessened when only the five trials with a low risk of bias were analysed (48). There have been other studies suggesting that homebased palliative care may reduce admissions to hospital and increase hospital involvement for people with frailty, advanced heart failure, COPD on home oxygen, metastatic cancer and severe dementia (49), with reduced healthcare costs. This was also shown in Australia where a home based service reduced hospital admissions and bed days and costs of acute care in the last year of life (50). Barriers were found to the early involvement of palliative care in hospital, including the staging of the disease, staff, patient and organizational barriers (51). The use of triggers to allow patients with palliative care need to be identified and then assessed was suggested (51).

As well as there being limited evidence for the involvement of palliative care, there is also a lack of clarity in how this could be provided. This is further complicated by the lack of clarity as to what is provided by palliative care—from general care to specialist team involvement, as shown in Box 1.

Full table

The models suggested by Bruera and Hui for cancer care could apply equally to other disease groups—from an independent practitioner approach to a congress approach to an integrated team approach (6). They have also suggested that there could be a provider based approach with increasing expertise from primary care to specialist palliative care (Figure 1) (19). However with this model there is a need for all health professionals to be aware of potential palliative care needs and to be able to address these, to a variable extent. A patient with minor symptoms may be cared for by a primary care team without any problems but more complex patients may require a more specialist approach. This may be by the use of regular assessment of patients’ needs, using a needs based tool, with triggering of more specialist help if issues are found. There are still issues about the timing of this onward referral, the availability of an infrastructure to respond to the referral, and the issues of terminology (52). Although the definitions of the various aspects of palliative care seem to be clear the reality may be more complex—as professionals may be reluctant to talk of palliative care or about possible progression and death, patients may find palliative care less acceptable and refuse to be involved and families may resist involvement as this is seen as accepting the progression and inevitability of death and losing hope (20).

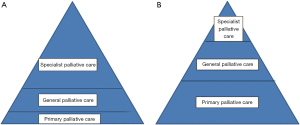

If the referral for palliative care is left to the main professional seeing the patient—oncologist, cardiologist, neurologist or other specialist—there may be delays as they find coping with these issues more difficult (19). If all patients have palliative care involvement, within an integrated model, this is lessened (6,19). However there may still be a variation in the skills of professionals and what seems to be clear lines of skill and involvement may vary from practitioner to practitioner (Figure 2). Some professionals, who feel that they lack the experience or skills to manage the issues of palliative care, or find it difficult to face these issues and discuss with patients may have a very low threshold to refer and involve other teams, early, and maybe inappropriately (Figure 2A). The more experienced professionals or teams may require less support from specialist teams (Figure 2B). Thus the referral may depend as much on the practitioner as the patient and family and their issues.

There is the need for further development in awareness, recognition of needs and ability to manage the issues that may arise. Another model has been to develop, through education, the primary professional team, as has been suggested for stroke care (34,36). This may improve the outcomes, but does depend on the attitudes and awareness of these teams (6). There is also the need for close collaboration with specialist palliative care services for advice and support with more complex issues. There are also issues of how the resources and time would be found for this education and the ensuing assessment at all consultations.

Increased collaboration and interaction between all involved—primary care, specialist teams and specialist palliative care—is another model for the future. This was shown in both the support of cancer and heart failure with either a palliative care assessment (10,15,16,41) or a member of the MDT providing palliative care (32,33,43). This will require increased education and the opportunities for teams to work together. This may be complex as although everyone assumes teams work in similar ways, there are often major differences in ethos, leadership styles, team dynamics, multidisciplinary working practices, and attitudes (53). These may need to be recognized and addressed for the care of patients and families to be maximized. There will also need to be clarity as to how the interaction will be undertaken. The use of regular assessment and triggering of palliative care within a clear pathway is one way forward. Education is needed for all involved, not only in the practical issues of patient care—physical, psychosocial and spiritual issues—but also the wider discussion and consideration of ethos, attitudes, coping with dying and death, coping with the more profound issues of both patient and family and how teams work individually and interact with others (53).

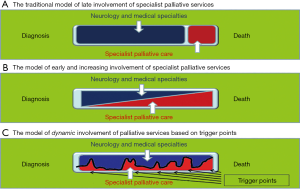

It has been suggested that palliative care may be needed episodically throughout the disease progression—as shown in Figure 3 (54). This was developed for neurology, but could be applied to all progressive diseases, as there has been the change from palliative care only being considered at end of life (as in Figure 3A), to a gradual change over time from the care of neurology or other specialities to palliative care (Figure 3B) to episodic care, according to need (Figure 3C). For instance for a person with MND/ALS this may be at diagnosis, when they face this little known disease and its implications, when gastrostomy may be considered, when non-invasive ventilation is assessed for cognitive change and towards the end of life, and this may be over a period of 2 to 3 years. For a more chronic disease the needs may arise over a longer period of time, even many years, but palliative care may be helpful for particular issues as the disease progresses. There will be the need for the specialist team to continue to be involved for many disease groups, as for instance in heart failure the adjustment of medication for the disease process itself can be helpful in managing symptoms, in association with palliative care interventions. This pattern of care may be applied for all diagnoses, as many diseases become more chronic, with variable exacerbations, and are faced by patients who have several comorbidities and the issues of ageing and frailty.

There is a challenge as to how the integration of palliative care can be improved, with the aim of improving patient outcomes. The evidence presented above suggests that the closer involvement and awareness of palliative care within any specialised service does tend to improve patient outcome—quality of life, symptom burden and possibly survival. There is uncertainty as to the best way to facilitate this improvement, but closer collaboration, imbedding of palliative care within teams, education of all involved in care to increase awareness of the palliative care needs of patients and families, clear pathways for referral and assessment of palliative care needs, availability of the resources to allow assessment and support and flexibility in the provision of palliative care.

Moreover there is the need to ensure that all involved—patients, families and professionals—are aware of the potential benefits of palliative care, as there are still many who see palliative care involvement only at the end of life. There is often resistance to assessment and involvement of palliative care as this adds to the fear of the future. The myths and fears of palliative care need to be faced and addressed by patients and families, professionals and wider society for palliative care to become more acceptable (55). There is the need for education at all levels and throughout society, so that patients and families are able to receive the care they need so that their outcomes may improve, and their quality of life is maximized, and death may be peaceful, with support of those involved before and after death.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- World Health Organization. Palliative care 2002. Available online: www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- Rosenwax LK, McNamara BA. Who receives specialist palliative care in Western Australia and who misses out. Palliat Med 2006;20:439-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Radbruch L, Payne S. Board of Directors of the EAPC. White Paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe: part 1. European Journal of Palliative Care 2009;16:278-89.

- Cherny NI, Kaasa S. The oncologist’s role in delivering palliative care. In: Cherny NI, Fallon MT, Kaasa S, et al. editors. Oxford textbook of Palliative Medicine 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015;750-1.

- Ahmedzai AH. The nature of palliation and its contribution to supportive care. In: Ahmedzai SH, Muers MF. editors. Supportive care in respiratory disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005;16-21.

- Bruera E, Hui D. Conceptual models for integrating palliative care at cancer centres. J Palliat Med 2012;15:1261-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lunney JR, Lynn J, Hogan C. Profiles of older Medicare decedents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1108-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis MP, Temel JS, Balboni T, et al. A review of the trials which examine early integration of outpatient and home palliative care for patients with serious illness. Ann Palliat Med 2015;4:99-121. [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Temel JS, Greer JA, El-Jawarhi A, et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: a randomised trial. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:834-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Pirl WF, et al. Effects of early integrated care on caregivers of patients with lung and gastrointestinal cancer: a randomised trial. Oncologist 2017;22:1528-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- BIakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer; the Project ENABLE II randomised controlled trial. JAMA 2009;302:741-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bakitas MA, Toteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: patient outcomes in the intervention on clinical outcomes in the ENABLE III randomised controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1438-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dionne-Odom JN, Azuero A, Lyons KD, et al. Benefits of early versus delayed palliative care to informal family caregivers of patients with advanced cancer: outcomes form the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1446-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;383:1721-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Dall’Agata M, et al. Systematic versus on-demand palliative care:a randomised clinical trial assessing quality of care and treatment aggressiveness near the end of life. Eur J Cancer 2016;69:110-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann C, Richelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, et al. Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: a systematic review. JAMA 2008;299:1698-709. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Groenvold M, Petersen MA, Damkier A, et al. Randomised clinical trial of early specialist palliative care plus standard care versus standard care alone in patients with advanced cancer: The Danish Palliative Care Trial. Palliat Med 2017;31:814-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hui D, Bruera E. Integrating palliative care into the trajectory of cancer care. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016;13:159-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhi WI, Smith TJ. Early integration of palliative care into oncology: evidence, challenges and barriers. Ann Palliat Med 2015;4:122-31. [PubMed]

- Gaertner J, Maier BO, Radbruch L. resource allocation issues concerning early palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2015;4:156-61. [PubMed]

- Clark, D. Cicely Saunders. Founder of the Hospice Movement. Selected Letters 1959-1999. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002;322-4.

- O'Brien T, Kelly M, Saunders C. Motor neurone disease: a hospice perspective. BMJ 1992;304:471-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oliver DJ, Borasio GD, Caraceni A, et al. A consensus review on the development of palliative care for patients with chronic and progressive neurological disease. Eur J Neurol 2016;23:30-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- End of life care in long term neurological conditions: a framework for implementation. National End of Life Care Programme 2010.

- Hussain J, Adams D, Allgar V, et al. Triggers in advanced neurological conditions: prediction and management of the terminal phase. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2014;4:30-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Edmonds P, Hart S, Gao W, et al. Palliative care for people severely affected by multiple sclerosis: evaluation of a novel palliative care service. Mult Scler 2010;16:627-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, McCrone P, Hart S, et al. Is short-term palliative care cost-effective in multiple sclerosis? A randomized phase II trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009;38:816-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Veronese S, Gallo G, Valle A, et al. Specialist palliative care improves the quality of life in advanced neurodegenerative disorders: Ne-PAL, a pilot randomized controlled study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7:164-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solari A, Giordano A, Patti F, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a home based palliative approach for people with severe multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2018;24:663-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Motor neurone disease: assessment and management. NICE Guideline NG 42. NICE 2016. Available online: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG42

- Aridegbe T, Kandler R, Walters SJ, et al. The natural history of motor neuron disease: Assessing the impact of specialist care. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2013;14:13-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rooney J, Byrne S, Heverin M, et al. A multidisciplinary clinic approach improves survival in ALS: a comparative study of ALS in Ireland and Northern Ireland. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;86:496-501. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eastman P, McCarthy G, Brand CA, et al. Who, why and when: stroke care unit patients seen by a palliative care service within a large metropolitan teaching hospital. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;3:77-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Casaubon LK, Boulanger JM, Glasser E, et al. Canadian Stroke Best Practice Recommendations: Acute Inpatient Stroke Care Guidelines, Update 2015. Int J Stroke 2016;11:239-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Creutzfeldt CJ, Holloway RG, Curtis JR. Palliative care: a core competency for stroke neurologists: acute stroke palliative care. Stroke 2015;46:2714-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med 2014;28:197-209. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Volicer L. Palliative care in dementia. Prog Pall Care 2013;21:146-50. [Crossref]

- Ponikowski P, Voors AV, Anker SD, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA). Eur Heart J 2016;37:2129-200. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brännström M, Boman K. Effects of person-centred and integrated chronic heart failure and palliative home care. PREFER: a randomised controlled study. Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:1142-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Evangelista LS, Lombardo D, Malik S, et al. Examining the effects of an outpatient palliative care consultation on symptom burden, depression and quality of life in patients with symptomatic heart failure. J Card Fail 2012;18:894-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ng AYM, Wong FKY. Effects of a home-based palliative heart failure program on quality of life, symptom burden, satisfaction and caregiver burden: a randomised controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:1-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lewin WH, Cheung W, Horvath AN, et al. Supportive cardiology: moving palliative care upstream for patients living with advanced heart failure. J Palliat Med 2017;20:1112-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Waller A, Girgis A, Davidson PM, et al. Facilitating needs-based support and palliative care for people with chronic heart failure: preliminary evidence for the acceptability, inter-rater reliability and validity of a needs assessment tool. J pain Symptom Manage 2013;45:912-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kane PM, Daveson BA, Ryan K, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a patient-reported outcome intervention in chronic heart failure. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7:470-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheang MH, Rose G, Cheung CC, et al. Current challenges in palliative care provision for heart failure in the UK: a survey on the perspectives of palliative care professionals. Open Heart 2015;2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gaertner J, Siemens W, Meerpohl JJ, et al. Effect of specialist palliative care services on quality of life in adults with advanced incurable illness in hospital. Hospice, or community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2017;357:j2925. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Dionne-Odom N, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016;316:2104-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lustbader D, Mudra M, Romano C, et al. The impact of home-based palliative care program in an accountable care organization. J Palliat Med 2017;20:23-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Youens D, Moorin R. The impact of community-based palliative care on utilization and cost of acute care hospital services in the last year of life. J Palliat Med 2017;20:736-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dalgaard KM, Bergenholtz H, Nielsen ME, et al. Early integration of palliative care in hospitals: A systematic review on methods, barriers, and outcome. Palliat Support Care 2014;12:495-513. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gaertner J, Wolf J, Hallek M, et al. Standardizing integration of palliative care into comprehensive cancer therapy – a disease specific approach. Support Care Cancer 2011;19:1037-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oliver D, Watson S. Multidisciplinary Care. In: Oliver D. editor. End of Life Care in Neurological Disease. London: Springer, 2012;113-27.

- Bede P, Hardiman O, O’Brannagain D. An integrated framework of early intervention palliative care in motor neurone disease as a model to progressive neurodegenerative disease. Poster at European ALS Congress, Turin. 2009.

- Abel J, Kellehear A. Palliative care reimagined: a needed shift. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2016;6:21-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]