Compassionate Communities in Canada: it is everyone’s responsibility

Introduction

In November 1986, the First International Conference on Health Promotion was held in Ottawa, Canada, in response to growing expectations for a new worldwide public health movement. The conference, which sought to identify action areas for health promotion to achieve “Health for all”, culminated in the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (1). Since the 1990s, the World Health Organization has been advocating a public health approach to palliative care (2,3). This approach, which originated in Australia, has since garnered support on an international scale. Inspired by these international movements, the Compassionate City Charter (CCC) was developed, applying the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion to palliative care (4). This charter is one of the drivers of the Compassionate Communities (CC) movement today.

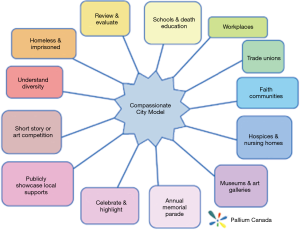

Based on the work of Prof. Allan Kellehear, the CC movement is a social model of palliative care, rooted in community development processes. It is a theory of practice for Health Promoting Palliative Care (HPPC), developed to form policy and practice coalitions of support for everyone affected by end-of-life events (5). It values: (I) a top-down, i.e., whole systems approach, which extends health services to community settings such as local government, workplaces, and schools; and (II) a bottom-up, i.e., health promoting approach, which demystifies caregiving, dying, death, and grieving through social and cultural sectors (e.g., museums, art galleries, media), to affect the greatest degree of change (6).

Kellehear defined a compassionate community as one that recognizes “all-natural cycles of sickness and health, birth and death, and love and loss occur every day within the orbits of its institutions and regular activities” (7). In a compassionate community it is everyone’s responsibility to care for each other during times of crisis and loss, and not simply the task of health professionals. The CCC, then, is a tool used to build CC which includes thirteen areas (e.g., schools, faith groups, institutions) in which social change is fostered.

In 2011, when Kellehear came to Canada to promote a public health approach to palliative care at a university level, which had long been embraced in other countries around the world, there was little support for the movement (8). Although in the last 2 years’ interest in palliative care from a clinical and community level in Canada has waxed and waned, the CCC has recently provided a viable tool to move forward at the community level. Today, public interest and enthusiasm for a theory of practice that helps us mobilize on palliative care is gaining momentum in Canada.

This article discusses the various ways that the CC movement is gaining momentum in Canada. It begins with describing the context of palliative care in Canada, including population concerns and federal legislative changes. It then discusses the opportunities and challenges faced by the CC movement in Canada. It concludes with a discussion of possible next steps towards supporting communities in which caregiving, dying, death, and grieving are everybody’s responsibility.

Palliative care in Canada

In Canada, this movement to broaden the scope and work in palliative care is especially timely. First, although the federal government passed a compassionate care leave benefit provisions in 2004, it had relatively low uptake until 2015 (9). Second, in 2016 the federal government modified the Criminal code to legalize Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) (10). Since then, provinces and territories have been working to introduce legislation and policies related to the oversight and delivery of MAiD in their respective jurisdictions. For example, in May 2017, the MAiD Statute Law Amendment Act came into force in Ontario. Finally, MAiD has inspired further focus in palliative care from several sectors.

In the wake of Canada’s assisted dying legislation, quality palliative care has become an even more pressing issue to offer patients a viable choice for their end-of-life care. MP Marilyn Gladu introduced Bill C-277, an Act providing for the Development of a Framework on Palliative Care in Canada. This Act requires the federal government to liaise with provincial health authorities to provide more clear definitions and support to palliative care providers and develop guidelines for consistent access to palliative care across the country. Gladu explained that “physician-assisted death cannot be truly voluntary if the option of proper palliative care is not available to alleviate a person’s suffering. Those that have access to quality palliative care choose to live as well as they can, for as long as they can” (11).

In addition, Canada is experiencing a surge of individuals who are living longer in declining health and presenting with more complex needs in the advanced stages of palliative care (12-14). For the first time in Canadian history, people aged 65 and older outnumber children under the age of 15. This rapid increase, due in part by aging baby boomers, represents a 20% jump since 2011. According to the latest census data, seniors now make up 16.9% of the Canadian population while children account for 16.6%, a demographic trend that is expected to continue over the next 2 decades. According to projections, the proportion of seniors will reach between 22.2% and 23.6% of the total population by 2030 and 23.8% to 27.8% by 2063 (15).

Given this fast-growing senior population, the home and community care workforce, as well as caregivers, are unprepared to deal with the growing demand. According to a 2012 Statistics Canada study, 13% of Canadians aged 15 and older had provided end-of-life care to a family member or friend at some point in their lives and 28% had provided care to a chronically ill, disabled, or aging family member or friend in the previous year (16). Sixty-five percent of respondents were under the age of 50 and 64% were juggling caregiving in addition to their regular paid work (17). Thirty-three percent of those helping a senior in a facility and 29% of those living with the recipient felt that it caused a strain with family members.

Attention to the challenges of palliative care and its effect on caregivers is additionally timely because the definition of palliative care is broadening (18). Beyond considering only people for whom death is imminent (more properly called end of life care), palliative care also includes individuals whose death from a chronic illness may take years. Six in ten Canadians suffer from a chronic illness or have a sufferer in their immediate family, and chronic illness accounts for 89% of deaths, thus generating considerable palliative care needs (19).

Significant gaps in Canada’s palliative care services make it costly and unreliable, which is detrimental to our chronically ill and aging population and to the sustainability of our healthcare system. Only 16% to 30% of dying Canadians have access to, or receive, palliative and end-of-life care services (20). In Ontario, the average cost for at-home palliative care is $100 per day. In comparison, someone occupying a hospice bed will cost roughly $460 per day; someone in an acute-care setting will cost roughly up to $1,100 per day (18). With the proportion of seniors predicted to rise, costs associated with end-of-life care will continue to multiply. CC would not only strive to improve health outcomes but also reduce health care inequalities among population groups (21,22).

Thus, enhancing senior care will entail increased focus on healthy aging, improved integration of health and social services; ensuring care is appropriate and timely, and providing supports for family and other caregivers. This is a significant undertaking which will benefit all Canadians in the long-term (23).

Pallium Canada and CC

A key advocate for improving the quality of palliative care services across the country is Pallium Canada. Founded in 2001, Pallium is a not-for-profit organization that first acted as a palliative-care delivery initiative for rural settings. It has since evolved from its roots as an applied research project, funded through Health Canada’s Health Human Resource Strategy, to become the sole national organization supporting continuing inter-professional palliative care education accredited by The College of Family Physicians Canada and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. Pallium works to empower primary care and non-specialist providers in the delivery of palliative care through its educational programs, tools and resources, improving the equity of access to palliative services and ensuring the comfort and dignity of Canadians throughout the illness journey. Since the early days of Pallium, a population health approach has been key to supporting patients and families through building community capacity/resilience and social change (5,24).

Principles that support Pallium’s work with CC

To support patients and their families who are facing life limiting illness a revised approach to palliative care is needed. Rather than focusing only on patients whose death is imminent, this palliative care approach includes early, compassionate and effective palliative care for all to better support their quality of life. Moreover, it focuses on physical, cultural, psychological, social, and spiritual needs for patients and families (caregivers), regardless of age or disease trajectory.

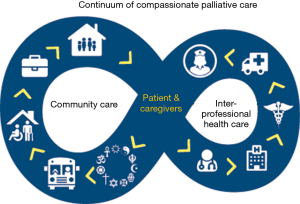

To support the palliative care approach, medical professionals, caregivers and community members need to be included in the continuum of care (Figure 1). The addition of community members helps to create a wrap-around effect to better support the patient and family dealing with a diagnosis pertaining to a life-limiting and/or life-threatening illness*.

This approach to palliative care is the essence of the CCC. The Charter is seen as a best practice framework which was designed to be expandable and flexible for creating a Compassionate Community in any setting (Figure 2). Additionally, the Charter is focused on caregiving, dying, death, and grieving which play a key role in supporting the death journey.

Challenges in building CC

The principle of compassion in communities is appealing across many sectors; however, there is some confusion in Canada due in part to the existence of other “compassion charter” work in North America. Specifically, the CCC has often been confused with the Charter for Compassion (27). The Charter for Compassion originated in 2009 with a vision to foster a world where everyone is committed to living by the principle of compassion, through compassion-driven actions in businesses, schools, healthcare, the arts, and so on. Whereas the Charter for Compassion is all encompassing, the CCC applies these same principles with a lens that focuses on caregiving, dying, death, and grieving. This confusion can present complications when engaging with key stakeholders and most specifically with politicians. While working on CC in Burlington and Niagara West, Ontario, for example, the author was challenged by politicians who asked what was the difference and why would one choose the narrowly-focused CCC over something that they saw as more inclusive. Clearly, it is important that this distinction be made to avoid further confusion and dissemination of misinformation among the health community and public (28). We often explain that, whereas the Charter for Compassion can be overwhelming in scope, the CCC offers a manageable first step to work towards the larger, more comprehensive objective of cultivating compassion worldwide.

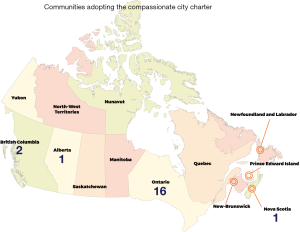

Given the universality of caregiving, dying, death, and grieving, palliative care is increasingly seen as a true public health issue. However, to affect maximum change, this recognition needs to extend at a national level, through government organizations such as the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Presently, PHAC does not recognize caregiving, dying, death, and grieving as an area of focus, despite Canada’s numerous CC and provincial initiatives (Figure 3). It does however, list seniors and aging as well as mental health as part of its priorities (30), which align with Compassionate Community priorities (e.g., mental health in terms of caregiver burnout, grief, etc.).

A national movement

In Canada, the CC approach to palliative care has already garnered considerable support on a regional, provincial, and national level, establishing the country as a leader of the movement. The Windsor-Essex Compassion Care Community initiative brings together stakeholders within this distinct Ontario region. Hospice Palliative Care Ontario (HPCO) has created a community of practice for CC to share best practices and support new CC projects. In British Columbia (BC), the BC Centre for Palliative Care (BC CPC) mobilizes and supports CC in BC through seed grants, tools, and coaching and partnerships (31). At the national level, Pallium Canada seeks to mobilize CC across the country. This growing work in CC has resulted in a range of initiatives in support caregiving, dying, death, and grieving throughout the country.

Engaging workplaces and employers

A fundamental understanding of the CCC is that caregiving, dying death, and grieving happen in our everyday activities and interactions, including in workplaces (7). For this reason, the Conference Board of Canada Palliative Care Matters report demands that there be more focus on the workplace (32). The federal government is cognizant of this and has been pushing for employers to support working Canadians who are caring for a loved one needing palliative care. In 2004 the government introduced the compassionate care benefit. Funded through federal Employment Insurance, this benefit allows Canadians to take a paid work leave for up to twenty-six weeks to care for a loved one whose death is foreseen in the next six months (33,34). Under Canada’s federal system, however, labor codes are managed provincially, and some provinces do not protect the jobs of individuals who take such a long leave of absence (34). Although there may be funding for such a leave, there is not necessarily job security. Addressing this problem requires federal and provincial coordination.

The Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association designed its “Canadian Compassionate Companies” program with this problem in mind (34). The program recognizes corporations that have formal policies in place to accommodate employees who require time off work to care for a family member. Companies with a Canadian Compassionate Company designation have policies that support their employees through the caregiving journey. These companies showcase the Compassionate Care Benefit and regardless of provincial limits on work leave, these companies guarantee job protection for the full term of the compassionate care benefit.

Offering death education to health professionals

According to the National Palliative Medicine Survey, the first-ever national survey of physicians who deliver palliative care in Canada, 84% of surveyed physicians providing palliative care consultation services worked part-time in palliative care and had no formal training (35). Since integration of palliative care principles into the educational curriculum is fairly recent and not universal, providers have not necessarily received quality (if any) training regarding the provision of quality palliative care. This goes to show that there is a need to educate all health professionals through an increase in education at all levels of schooling as well as continuing education.

One of the ways in which this can be accomplished is via The Way Forward framework. Developed by the Quality End of Life Care Coalition of Canada (QELCCC), The Way Forward is designed to create a cultural shift towards better support for residents who are dealing with death, dying and loss. The framework features Pallium’s Canadian-made curriculum Learning Essential Approaches to Palliative Care (LEAP), which was developed as interprofessional courseware to foster a broad community network, promote positive attitudes towards palliative care, and thus move toward a compassionate social environment. In March 2017 Pallium piloted LEAP Health Sciences, tailored to undergraduate students completing their health science or public health degrees. LEAP Health Sciences discusses among other things, palliative care and the role of CC. Due to its success, the Dean of the Faculty of Applied Health Science at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario, is looking to implement it as a 4th-year level course for students in medical science, public health, and gerontology, and elective to other programs such as social sciences (36).

Private member’s Bill C-277

A major milestone was reached on December 8, 2017, when Sarnia Lambton MP Marilyn Gladou’s bill providing for the development of a framework designed to support improved access for Canadians to palliative care, passed the 3rd reading in the Senate, receiving unanimous support from the House of Commons and Senate (37). Hereafter, the Minister of Health will collaborate with representatives of the provincial and territorial governments responsible for health, as well as palliative care providers, to develop a palliative care framework that will: (I) define palliative care; (II) identify required training and education for health care providers; (III) outline measures to support palliative caregivers; (IV) collect research and data on palliative care; (V) identify measures to ensure consistent access to palliative care across Canada; and (VI) evaluate the advisability of amending the Canada Health Act to include palliative care services provided through home care, long term care facilities, and residential hospices (35).

A number of faith groups have been long-time supporters of the bill. The Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, along with groups from the Jewish, Catholic, and Muslim communities is calling for a framework to ensure high-quality palliative care (38). Their enthusiasm was expressed to the Senate in an interfaith letter of support sent encouraging Senators to vote in favor of Bill C-277 (39).

Creating communication campaigns

Both The Way Forward and Palliative Care Matters have highlighted a clear need for a communication strategy to inform Canadians about palliative care and the importance of having an open conversation regarding their dying journey. For example, public input from the Palliative Care Matters initiative stressed the need for increased communication and understanding of the federal government’s compassionate care benefit program available to caregivers (32). This would be an excellent example of how PHAC could use their expertise in this new area of focus.

CCC in Action

Opportunities for partnerships and collaboration

Collaborating with other community stakeholders, piloted initiatives, and charters with common interests will expand the CC movement. The goal is not to duplicate, but rather, supplement well-rooted charters to include objectives that relate to caregiving, dying, death, and grieving. By aligning with established charters, fewer funds and resources are required to expand it. For example, Age Friendly Communities (40) and Dementia Friendly Communities (41), movements to reduce stigma around ageing and dementia and enhance respect for older persons, are two programs that connect well with the CCC. Applying the lens of caregiving, dying, death, and grieving, to such existing initiatives, will ensure quicker spread and increased sustainability of the CC movement.

Canada hosted of the Fifth International Public Health Palliative Care conference in the fall of 2017. There was much interest from the delegates to learn how CC within Canada was engaging with sectors of the charter. This next section covers several of the key areas of interest in which engagement has begun, and other factors that should be considered.

Building CC through education

Despite the importance of involving everyone in the palliative process, there remains a taboo surrounding dying, death, and grieving in Canada that has perpetuated a culture of reluctance and even fear. In order to create lasting social changes that will foster a culture of compassion and shared responsibility for end-of-life care, education and public openness about death is essential (42). By normalizing openness toward end-of-life, we remove the stigma associated with death and create opportunities for discussion, strengthening linkages across the continuum of care settings (Figure 1) to ensure that Canadian seniors, people with disabilities and chronic disease, and patients receiving post-acute care, don’t fall through the cracks.

Education is considered by CC as one of the most difficult areas in which to engage. Teachers have expressed concern about how to broach the topic of death with their students. Schools do not always have response protocols in place that make clear how to support students coping with the death of a loved one. For this reason, doctors, palliative care advocates, and educators alike, are urging schools to include death education into their curriculums, so that teachers can feel comfortable talking about dying, death, and grieving in the classroom (43,44).

Communities are using the CCC to increase access to death education within the education system and promote the development of compassionate schools. Through school, community members recognize that death is ubiquitous, and they are not properly equipped with the knowledge, skills, and resources to support individuals dealing will loss. Compassionate schools, which incorporate death education into their curriculums, policies, and approaches, are communities of teachers, staff, parents, and students of all ages, who provide compassion, care, and support to one another during these difficult times.

A similar example of proposed education that was met with great discomfort was seen in the recent release of Ontario’s updated Health and Physical Education Curriculum (45). Parents voiced their disagreement regarding lessons about sexuality, some even opting to remove their children from sex education classes (46). Many criticized the revised curriculum for being age-inappropriate—discussing topics they deemed explicit and challenging heteronormativity (47). Nevertheless, the government stood firm on its commitment to the curriculum, explaining that it was necessary to keep children safe considering changes in technology (48).

The same can be said about death education. Just as sex is a natural part of the life cycle, so as is death, and schools have a role in preparing students. Should death education also be included in school curriculums, it is fair to assume that a similar outcry will ensue. Not unlike sexual health education, death education will need to be impartial and sensitive to religious and cultural objections (49). Although practices surrounding caregiving, grieving, and memorializing loved ones are all culturally-bound, death is universal. By introducing death education into schools, people can become comfortable with the idea that death is unavoidable. What’s more, children and youth develop better communication and decision-making skills, increase their self-esteem, and develop more positive relationships (50).

In Canada, there are two curriculums available in both official languages that deal with death and loss. The first, Zippy’s Friends, teaches children ages 6 to 7 how to cope with life’s inevitable ups and downs—including death—and even includes a visit to a cemetery (51). The second, Passport: Skills for Life, is a PHAC funded initiative designed to help children between 9 and 11 years of age to cope with loss and touches on death and bereavement (52). This program is currently being taught in public, faith-based, and Indigenous schools. It also includes a 2-day training course for teachers to explore their own interactions with death prior to moving on to the curriculum itself. In addition, tailored resources and workshops are available to parents to address any concerns they may have prior to the launch of the curriculum. Meanwhile, for those who do not have access to death and grief education, the Canadian Virtual Hospice hosts a free monthly webinar called “Kids Grief” and recently released a toolkit that allows parents, social workers, and teachers to talk to a grieving child about grief and death, including death by suicide (53).

Unfortunately, these curriculums are not the norm and death education is not readily available to most students in Canada. Thus, the first step in integrating death education into school curriculums is to standardize the education systems. Death education, like sex education, should be consistent across school boards. Moreover, measures must be taken to ensure that the distribution of teachers, class size, education funding, and evaluation methods, are carefully thought out as to not overload teachers (49).

Teachers have shown significant interest in implementing death education into school curriculums. As part of a public health project, a student under the supervision of Bonnie Tompkins (Compassionate Communities National Lead) held focus groups with educators who expressed feeling unequipped to deal with death and unsure where to get the necessary information and training to help their students (44). One teacher shared that she was dying and did not know how to discuss it with her students. In another instance, two teachers felt unfit to deal with a child whose father had died by suicide. They did not have the resources to help them with this situation, a challenge compounded by the fact that the student was on the autism spectrum. In the complex modern classroom, teachers who are properly prepared to discuss such a sensitive topic as death may find such challenges easier to negotiate.

Compassionate workplaces

The activities and initiatives at the national level can also help local compassionate community organizations to encourage employers to develop compassionate workplace policy. With progress being made through the Compassionate Care Benefit at a national level, the CC movement is garnering support, thus setting a new tone for office culture and shaping a workplace environment that is conducive to compassionate workplaces. Supporting caregivers is imperative for patients, their families and friends, and the community at large, and employers have an important role to play in advocating on their behalf.

Such workplace initiatives can also create an awareness of the array of emotions experienced by a caregiver or a dying employee/co-worker. Having a loved one who is dying and/or near death is incredibly demanding on an employee who is juggling their care work with their employment. When coworkers and employers understand the difficulties involved with looking after a loved one who is ill, they learn to appreciate the process of the cycle of life, value the benefits of compassion, and learn to recognize their role as part of a Compassionate Community (54). Establishing proactive policy and instilling a sensitivity to the emotional impact experienced by caregivers and dying employees, employment-based initiatives provide employers with strategies to ensure appropriate and sensitive handling of death in the workplace (55).

Faith Communities’ great interest in CC

Partnering with faith communities can offer an approach to palliative care grounded in the CC model. The MAiD legislation has increased interest among faith communities on the needs for accessible and comprehensive palliative care. Recently, Kyle Ferguson, Advisor for Ecclesial and Interfaith Relations with the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, spoke on a panel at the Pallium Canada Mobilizing Compassionate Communities: Take 2 event (56). The Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops assists dioceses in promoting palliative care and end-of life education in parishes, schools and hospitals, even encouraging Catholic schools to develop and undertake palliative care education in classrooms and introduce students to the language and practice of palliative care. It is also looking to develop a presentation that utilizes the CC model to address questions surrounding palliative care, dying, death and suffering by clarifying the relationship between the medical practices of palliative care and how it relates to theology —showing how palliative care is medically and morally distinct from MAiD.

In the same vein, Pallium is developing a toolkit that defines basic palliative care terminology (e.g., MAiD, Do Not Resuscitate, etc.) for the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops. It will help demystify how death and palliative care intersect with theology and will serve as a CC education tool. It will contain three modules, two of which will be applicable to Jewish and Muslim faiths, allowing faith communities to tailor the module to their needs. At the time of writing, plans have been made to host focus groups in Catholic parishes in 2018.

Evaluating CC

Evaluating volunteer-led projects operating within the CC model has been a challenge. Because many initiatives are not-for-profit and volunteer based, funding and resources allocated to develop evaluation tools has been limited. The thirteenth area of focus in the CCC, mandates evaluations to measure the success and usefulness of CC initiatives to justify their presence, their funding, and their support. For this reason, Pallium in partnership with CC initiatives across the country, is applying for funding to develop these tools, which will allow them to assess project performance.

Pallium Canada—mobilizing CC

Pallium is focused on mobilizing the spread of CC across Canada and has identified several key areas where it can provide support. The first toolkit covers core aspects of successfully initiating a compassionate community. The workplace toolkit is currently under development. Subsequent toolkit topics may cover neighborhoods and death education. In addition, Pallium is hoping to partner with organizations focused on supporting grassroots community projects to create best practices tools.

Opportunities to engage community members and stakeholders are also a key priority for Pallium. For example, Pallium is hoping to host annual connection events (either virtually or in person) such as the Take 2 event, which in September 2017, brought CC initiatives together from across the country (56). Such events will enable champions of local CC initiatives to celebrate and learn from pan-Canadian projects to build and support a broader compassionate country. Additionally, Pallium is looking to develop a web-based platform for people involved in CC to connect and collaborate in real-time.

Finally, the Board of Directors recently appointed Jeffrey Moat as their new CEO. Prior to joining Pallium, Moat was the President of Partners for Mental Health, a national charitable organization dedicated to transforming the way Canadians think about, act towards and support mental health and wellbeing. The work that Moat’s organization achieved helped to inspire a social movement that raised awareness, changed attitudes, spurred action and generated the systemic changes essential to making real progress in mental health services. As Moat steps into his new role at Pallium, it is anticipated that he will be equally influential and instrumental in delivering against the organization’s vision of ensuring that every Canadian who requires palliative care will receive it early, effectively and compassionately (57).

Next steps for Canada

The CC movement has grown and gained significant support since 2011, when Kellehear first introduced a public health approach to palliative care in Canada. The evolution of this social movement has not been without its downfalls. For all of its strengths today, the CC movement has a significant amount of growing to do. Some supports that are still very much needed include the collaborations of the PHAC, support for teachers and staff who are working with students, and a clear way to differentiate the two charters to alleviate possibility of confusion that may exist when talking about CC, for example employing branding strategies which could include developing a logo for the CCC.

The passage of Bill C-277, provides an excellent opportunity to advance the ideas of CC. National interest in improving palliative care will benefit from the principles embraced by the CC movement. It is imperative that proponents of CC maximize on this national conversation to demonstrate how the ideals of CC help to address this identified need for improved palliative care. We need to continue to develop policy and practice coalitions of support for everyone touched by end-of-life events in community settings such as local government, workplaces, and schools, as well as normalize caregiving, dying, death, and grieving through social and cultural sectors.

Clearly Canada has come a long way in a relatively short time to support caregiving, dying, death, and grieving. Major developments, including the emergence and collaboration of various supporting agencies for CC at the regional, provincial and national level; the Conference Board of Canada’s Palliative Care Matters report advocating a focus on workplaces and a national communication campaign around palliative care; and the passage of Bill C-277 calling for a national framework on palliative care have advanced attention on palliative care across the country. Although much more needs to be done, the principles of CC, and the important framework provided by the CCC have enabled like-minded advocates to identify areas of common interest, develop broad strategies, and reiterate the idea that caregiving, dying, death, and grieving are everybody’s responsibility.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to extend her gratitude to Dan Malleck, Julie Boucher and Kirsten Efremov for their writing support; to Dr. Denise Marshall for her collection of the background information; and to Kim Martens for her editing support.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author is an employee of Pallium Canada.

References

- Government of Canada. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. 1986. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/health-promotion/population-health/ottawa-charter-health-promotion-international-conference-on-health-promotion.html

- Stjernswärd J. Palliative Care: The Public Health Strategy. J Public Health Policy 2007;28:42-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Batiste X, Caja C, Espinosa J., et al. The Catalonia World Health Organization Demonstration Project for Palliative Care Implementation: Quantitative and Qualitative Results at 20 Years. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;43:783-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Compassionate City Charter. Available online: http://www.phpci.info/tools/

- Kellehear A. Health Promoting Palliative Care: developing a social model for practice. Mortality 1999;4:75-82. [Crossref]

- Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians. How to improve palliative care in Canada: A call for action for federal, provincial, territorial, regional and local decision-makers. 2016. Available online: http://www.cspcp.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Full-Report-How-to-Improve-Palliative-Care-in-Canada-FINAL-Nov-2016.pdf

- National Council for Palliative Care (NCPC). Public Health Approaches to End of Life Care: A Toolkit. Available online: http://www.ncpc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Public_Health_Approaches_To_End_of_Life_Care_Toolkit_WEB.pdf

- Smith T. Welcome—Dr. Allan Kellehear. Dalhousie University. 2011. Available online: https://blogs.dal.ca/fhp/2011/09/20/welcome-dr-allan-kellehear

- Crooks VA, Williams A. An Evaluation of Canada’s Compassionate Care Benefit from a family caregiver's perspective at end of life. BMC Palliat Care 2008;7:14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- An Act to amend the Criminal code and to make related amendments to other Acts (Medical Assistance in dying). Status of Canada, 2016. Available online: http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/2016_3.pdf

- Marilyn Gladu. MP Marilyn Gladu introduces Bill C-277: An Act Providing for the Development of a Framework on Palliative Care in Canada. 2016. Available online: http://www.marilyngladu.com/news/mp-marilyn-gladu-introduces-bill-c-277--an-act-providing-for-the-development-of-a-framework-on-palliative-care-in-canada

- Lynn J. Sick to death and not going to take it anymore! Reforming health care for the last years of life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2014.

- Lynn J, Schuster JL, Wilkinson A, et al. editors. Improving care for the end of life. A sourcebook for health care managers and clinicians. 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Pereira JL. The Pallium Palliative Pocketbook: A Peer-reviewed, Referenced Resource. 2nd edition. Edmonton: The Pallium Project, 2008

- Bohnert N, Chagnon J, Dion P, et al. Population Projections for Canada (2013 to 2063), Provinces and Territories (2013 to 2038). Statistics Canada, 2017. Available online: https://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-520-x/91-520-x2014001-eng.htm

- Turcotte M. Family caregiving: What are the consequences? Statistics Canada, 2013. Available online: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-006-x/2013001/article/11858-eng.pdf

- Canadian Home Care Human Resources Study. Canadian Home Care Association. 2003. Available online: http://www.cdnhomecare.ca/media.php?mid=1030

- 2014 Annual Report of the Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. Office of the Auditor General of Ontario. 2014. Available online: http://www.auditor.on.ca/en/content/annualreports/arreports/en14/308en14.pdf

- Leading causes of death, by sex. Statistics Canada. 2017. Available online: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/hlth36a-eng.htm

- Health Care Use at the End of Life in Western Canada. Canadian Institute for Health Information. 2007. Available online: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/end_of_life_report_aug07_e.pdf

- Hayes MV, Dunn JR. Population health in Canada. A systematic review. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Policy Research Networks, 1998.

- Keon WJ, Pépin L. Population health policy: issues and options, Fourth report of the Subcommittee on Population Health of the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology. Senate of Canada. 2008. Available online: https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/Committee/392/soci/rep/rep10apr08-e.pdf

- The state of seniors health care in Canada. Canadian Medical Association. 2016. Available online: https://www.cma.ca/En/Lists/Medias/the-state-of-seniors-health-care-in-canada-september-2016.pdf

- Aherne M, Pereira JL. Learning and development dimensions of a pan-Canadian primary health care capacity-building project. Leadership in Health Services 2008;21:229-66. [Crossref]

- Tompkins B. Pallium Canada Mobilizing Compassionate Communities. 5th International Public Health and Palliative Care Conference—IPHPC 2017. Ottawa (Canada), 2017.

- Tompkins B. The Compassionate City Model of the 12 social changes framework based on the Compassionate City Charter by Allan Kellehear. 5th International Public Health and Palliative Care Conference—IPHPC 2017. Ottawa (Canada), 2017.

- Charter for Compassion. 2017. Available online: https://charterforcompassion.org/

- Russell C. Commentary: Compassionate communities and their role in end-of-life care. University of Ottawa Journal of Medicine. 2017. Available online: https://uottawa.scholarsportal.info/ojs/index.php/uojm-jmuo/article/view/1551/1773

- Tompkins B. Building Compassionate Communities through school, workplace and faith initiatives. 5th International Public Health and Palliative Care Conference—IPHPC 2017. Ottawa (Canada), 2017.

- 2017–18 Departmental Plan: Public Health Agency of Canada. Government of Canada. 2017. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/transparency/corporate-management-reporting/reports-plans-priorities/2017-2018-report-plans-priorities.html

- Tompkins B, Cruz I, Ali A. et al. Implementing Compassionate Communities in Canada: Emerging Approaches. Poster presented at the 5th International Public Health and Palliative Care Conference—IPHPC 2017. Ottawa (Canada), 2017.

- Stonebridge C. Palliative Care Matters: Fostering Change in Canadian Health Care. The Conference Board of Canada. 2017. Available online: http://www.conferenceboard.ca/e-library/abstract.aspx?did=8807

- Williams AM. Evaluating Canada's Compassionate Care Benefit using a utilization-focused evaluation framework: successful strategies and prerequisite conditions. Eval Program Plann 2010;33:91-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Backgrounder: Canadian Compassionate Companies. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association. 2016. Available online: http://www.chpca.net/projects-and-advocacy/ccc.aspx

- Highlights from the National Palliative Medicine Survey. Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians Human Resources Committee. 2015. Available online: http://www.cfpc.ca/uploadedFiles/Publications/News_Releases/News_Items/oldNews/PM_Survey_Final_Report_EN.pdf

- Pereira J, Tompkins B, Cruz I. et al. Educating Future Health Professionals: Pallium Canada’s LEAP Health Sciences Curriculum. Poster presented at the 5th International Public Health and Palliative Care Conference—IPHPC 2017. Ottawa (Canada), 2017.

- C-277, An Act providing for the development of a framework on palliative care in Canada. Parliament of Canada. 2017. Available online: http://www.parl.ca/LegisInfo/BillDetails.aspx?Language=E&billId=8286156

- Bill C-277 (2016-2017): Developing a palliative care framework. The Evangelical Fellowship of Canada. 2017. Available online: https://www.evangelicalfellowship.ca/c277

- Interfaith Letter to Senators on Palliative Care Bill C-277. The Evangelical Fellowship of Canada. 2017. Available online: https://www.evangelicalfellowship.ca/Communications/Outgoing-letters/October-2017/Interfaith-Letter-to-Senators-on-Palliative-Care-B

- Age Friendly Communities: Tools for Building Strong Communities. University of Waterloo. 2017. Available online: http://healthy.uwaterloo.ca/~afc/

- Dementia in Canada: A National Strategy for Dementia-friendly Communities. Senate of Canada. 2016. Available online: https://sencanada.ca/content/sen/committee/421/SOCI/Reports/SOCI_6thReport_DementiaInCanada-WEB_e.pdf

- Kellehear A. Commentary: Public health approaches to palliative care – the progress so far. Prog Palliat Care 2016;24:36-8. [Crossref]

- Sturino I. Why an ICU doctor says death ed is as essential as sex ed in high school. CBC Radio. 2017. Available online: http://www.cbc.ca/radio/thecurrent/the-current-for-april-11-2017-1.4064410/why-an-icu-doctor-says-death-ed-is-as-essential-as-sex-ed-in-high-school-1.4064606

- Guest M. Death, Dying, and Grief Supports for the Classroom [unpublished HLSC 4F44 dissertation]. St Catharines (CA): Brock University, 2017.

- The Ontario Curriculum: Elementary. Ontario Ministry of education. 2015. Available online: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/curriculum/elementary/health.html

- Keenan RC. Hesitant parents explain their unease with revamped sex ed curriculum. The Globe and Mail. 2017. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/parenting/hesitant-parents-explain-their-unease-with-revamped-sex-ed-curriculum/article23312617/

- Rathus S. Nevid J. Fichner-Rathus L. et al. Sexual Health Education. In: Human Sexuality in a World of Diversity. 5th ed. Toronto: Pearson Canada Inc., 2016.

- The Canadian Press. Ontario sex ed curriculum: 5 things to know. CBC News. 2015. Available online: http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/ontario-sex-ed-curriculum-5-things-to-know-1.3059951

- DeJong J. Comprehensive sexuality education: The challenges and opportunities of scaling-up. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. 2014. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002277/227781E.pdf

- Clarke AM. An Evaluation of Zippy’s Friends, an emotional wellbeing programme for children in primary schools. National University of Ireland Galway. 2011. Available online: https://aran.library.nuigalway.ie/bitstream/handle/10379/2624/Thesis_Aleisha%20Clarke.pdf?sequence=1

- Zippy’s Friends. Partnership for Children. 2017. Available online: http://www.partnershipforchildren.org.uk/zippy-s-friends.html

- Passport: Skills for Life. Partnership For Children. 2017. Available online: http://www.partnershipforchildren.org.uk/teachers/passport-skills-for-life.html

- KidsGrief.ca. Canadian Virtual Hospice. 2017. Available online: http://kidsgrief.ca

- Tehan M, Thompson N. Loss and Grief in the Workplace: The Challenge of Leadership. Omega (Westport) 2012-2013;66:265-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bouw B. Dealing with death at work. The Globe and Mail. 2014. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/careers/career-advice/life-at-work/dealing-with-death-at-work/article20962186/

- Mobilizing Compassionate Communities: Take 2. Pallium Canada. 2017. Available online: http://pallium.ca/cc/mobilizing-compassionate-communities-take-2/

- Pallium Canada Appoints Jeffrey Moat as Chief Executive Officer. PR Newswire. 2017. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/pallium-canada-appoints-jeffrey-moat-as-chief-executive-officer-300562037.html