Embracing the setting sun: provision of palliative care via a collaborative model between hospital and community for patients with intellectual disabilities

Palliative care (PC) evolved from taking care of terminal cancer patients to modern concept of early integration into disease trajectories of patients with life limiting cancer and non-cancer diseases (1). However, PC for patients with moderate to severe developmental intellectual disabilities (ID) was seldom discussed in literature (2). Care of ID patients at end of life is often fragmented. Symptom management is difficult for unfamiliar doctors because of communication difficulty. Family caregivers often have been caring these dependent patients for long time and they are at increased risk of bereavement. Therefore ID patients represent a unique group for which PC is important and is best delivered via a collaborative model between PC team and community ID service (3).

Since 2008, our PC unit piloted to provide PC to ID patients living in a rehabilitation complex serving ID people. Our hospital based PC team worked closely with the community PC team there, which comprises of social workers and nurses with PC training and experience. Referral criteria were based on gold standard framework for cancer and non-cancer diagnosis (4). The one year survival question was initiated by the experienced staff in the residential home. Symptom control, enhanced psychosocial care and end of life discussions were offered.

Comprehensive medical history was reviewed and explained. Patient information was collaterally collected across different disciplines including nurse, social worker, physiotherapists and occupational therapists. In order to have mutual understanding of patient management, family conference was conducted together with patients, their main caregiver, residential home staff including nurses and case social worker. Possibility of maximizing patient autonomy was explored, depending on the level of mental capacity of the patient, by trying to explain and allowing the patient to express as much as possible with the help of the staff and family.

Advance care planning (ACP) was done whenever possible, eliciting the preference of care, goal of care, place of care, and end of life care. Specific attentions were paid to explore patient preference, character and habits. Medical follow ups and continuous update on patient condition with family and care team were provided.

Enhanced psychosocial support (5) would be provided to patient and family. Home care nurse service was arranged to deal with complex psychosocial symptoms and complex grief of family, together with provision of medical help and knowledge in the care of the patient. Social care was enhanced with coordination of volunteer support, life reviews, art therapy and family support provided by the community team. Clinical psychologist was referred for highly complex or potentially pathological psychological problems.

For those wish to have end of life care in the residential home, medical support would be enhanced and nurse visit will be offered to support their end of life care. Direct admission to PC unit could be offered in selected cases to facilitate the care process. Bereavement service would be provided for complicated cases.

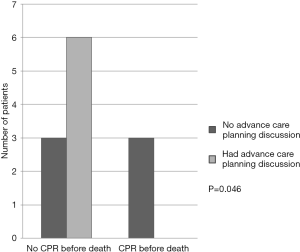

Case records of the ID patients referred for PC services from January 2008 to August 2014 were reviewed. Totally, 24 patients (54.2% male) were followed up for a median of 22 months (range 1 to 74 months). Mean age of patients was 50.3 (SD 11.7). Mean number of symptoms was 2.2 (SD 1.2), which included pain, constipation, weight loss, skin wound, spasticity and edema. 38% family main carer expressed sadness and helplessness on initial assessment. 38% of patients had ACP discussed which included end of life issues, identification of goal of care and cardiopulmonary resuscitation preference. ACP discussion was associated with no cardiopulmonary resuscitation done before death (P=0.046, Figure 1). Half of the patients died during follow up. The main cause of death was infection (68%).

Discussion

ID patients have specialist PC needs because of their complexity in medical and psychosocial issues. Discussion of ACP is often challenging. We echoed with Wagemans et al. (6), highlighting the dilemmas and uncertainties for ID physicians to discuss do-not-attempt-resuscitation orders for ID patients. Evaluation of quality of life was often left to the relatives and conflicts between physicians and relatives might arise. Furthermore, with the longer survival of patients with ID nowadays, their care-givers, often their parents are getting old also. They have to face their own aging and disability while taking care of their loved ones. They often shouldered the caring burden for most of their life. Grieving and adjustment are often tough. Therefore, it was not surprising we showed that a significant of family expressed hopelessness when they were facing the illness of the patient.

Tuffrey-Wijine et al. pointed out that the integration of ID expertise with mainstream PC teams may be the most appropriate model for PC provision in this special subgroup (7). It was a consensus that sharing the expertise of mainstream PC service with community team specializing in ID care is beneficial (8). Symptoms are prevalent near end of life in ID patients (9), but they are often difficult to identify. Symptom control is often challenging because of the difficulty of communication between health care professionals and patients. Therefore, role of care-givers (nurse and social workers) in the residential home is important, they can act as bridge between the patient, family and the team. Their observations often can be valuable in providing clues for physicians to help patients. Therefore, doctor visit at the residential home enables assessment of patient at the most familiar environment to reduce unnecessary stress. Direct communication between the care-givers, family, and the health care team is essential.

We believed ID patients and their family had significant PC needs. We showed that successful PC service can be provided for ID patients through collaborative model between hospital based medical PC team and community based PC team. Our preliminary result showed prior ACP discussion with family members and main caregivers was associated with less aggressive care at the end of life.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Fallon M, Foley P. Rising to the challenge of palliative care for non-malignant disease. Palliat Med 2012;26:99-100. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tuffrey-Wijne I. The palliative care needs of people with intellectual disabilities: a literature review. Palliat Med 2003;17:55-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin D, Barr O, McIlfatrick S, et al. Developing a best practice model for partnership practice between specialist palliative care and intellectual disability services: a mixed methods study. Palliat Med 2014;28:1213-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas K. The GSF prognostic indicator guidance. End of Life Care 2010;4:62-4.

- Chan KY, Yip T, Yap DY, et al. Enhanced Psychosocial Support for Caregiver Burden for Patients With Chronic Kidney Failure Choosing Not to Be Treated by Dialysis or Transplantation: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Kidney Dis 2016;67:585-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wagemans AM, van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk HM, Proot IM, et al. Do-Not-Attempt-Resuscitation orders for people with intellectual disabilities: dilemmas and uncertainties for ID physicians and trainees. The importance of the deliberation process. J Intellect Disabil Res 2017;61:245-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tuffrey-Wijine I, Hogg J, Curfs L. End-of-Life and Palliative Care for People with Intellectual Disabilities Who have Cancer or Other Life-Limiting Illness: A Review of the Literature and Available Resources. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil 2006;20:331-44. [Crossref]

- Tuffrey-Wijne I, McLaughlin D, Curfs L, et al. Defining consensus norms for palliative care of people with intellectual disabilities in Europe, using Delphi methods: A White Paper from the European Association of Palliative Care. Palliat Med 2016;30:446-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vrijmoeth C, Christians MG, Festen DA, et al. Physician-Reported Symptoms and Interventions in People with Intellectual Disabilities Approaching End of Life. J Palliat Med 2016;19:1142-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]