Implementing the Namaste Care Program for residents with advanced dementia: exploring the perceptions of families and staff in UK care homes

Introduction

Worldwide estimates indicate that 46.8 million people are living with dementia; a number expected to double every 20 years (1). Progression of Alzheimer’s disease and other progressive degenerative dementias leads to the inability to participate in traditional activity programs (2-4). Therefore, residents with advanced dementia are often isolated in their rooms or left alone in sitting rooms. Particular challenges of dementia care include: coping with behavioral and psychological symptoms (5); and, the prolonged, unpredictable course of deterioration over years (6). No cure is currently available, so research focused on improving quality of life for people with dementia is needed.

A palliative care approach to dementia is now widely accepted (7), with quality of life for the patient and his/her family established as the principal goal of care. Knowledge of the later stages of dementia and understanding of the palliative care needs of this population and their families remains limited (8,9). Specialist palliative care was developed to meet the needs of cancer patients, but the slow, uncertain course of dementia requires a different model of care (9,10). Although future healthcare planning and symptom management promote comfort and protect people with advanced dementia from inappropriate hospitalisations and futile medical interventions towards the end of their lives (11), such strategies do little to address their psycho-social and spiritual needs.

An Alzheimer’s Society survey in 2013 found that only 41% of relatives felt their relative in a care home had a good quality of life, with only 44% of family members reporting that opportunities for activities were good (12). An earlier survey found that typically, a care home resident spent only two minutes interacting with staff or other residents over a 6-h period of observation, excluding time spent on care tasks (13). Both reports uncovered a failure to treat people with dementia with courtesy and respect.

Person-centred care is recommended by national guidelines (14), and accepted as fundamental to achieving good quality of life for people with dementia. Kitwood (15) outlines the five main psychological needs of people with dementia: the need for attachment; comfort; identity; occupation; and inclusion.

Well-being and quality of life are difficult to measure for people unable to communicate easily (16,17). Therefore, measures of ill-being are often used as proxy measures, e.g., reduced agitation suggests enhanced well-being, which in turn suggests improved quality of life. Psychosocial and sensory interventions are often effective in relieving agitation for people with advanced dementia (18).

The Namaste Care program is a multi-dimensional care program with sensory, psycho-social and spiritual components intended to enhance quality of life for people with advanced dementia (19,20). The program addresses the psychological needs of people with dementia identified by Kitwood (15) (see Table 1), and strives to maintain their personhood respectfully and lovingly, which is the essence of person-centred care.

Full table

This paper reports qualitative findings from an action research study implementing and evaluating Namaste in the UK. The quantitative results of this study, reported elsewhere (21), found a reduction in the frequency and severity of behavioral symptoms.

Methods

The study was underpinned by an organisational action research design (22). Hart and Bond (22) describe a typology of action research intended to define the researcher’s purpose in undertaking the study: this ranges from experimental action research at one end of the continuum through organisational, professionalising types, with empowering action research at the other end of the continuum. The purpose of this study was to introduce Namaste and work collaboratively with the staff to evaluate its effects. The idea for the study originated with the researchers rather than care home staff, and so leaned towards organisational action research, where the topic/intervention originates with the researchers.

The intervention—the Namaste Care programme (Namaste)

‘Namaste’ is the Indian greeting meaning ‘to honor the spirit within’. Namaste was developed for care home residents with advanced dementia who can no longer engage in conventional group activities (19,23). Namaste combines compassionate care with meaningful activity in a dedicated, peaceful environment together with ‘loving touch’.

Namaste is a seven day/week programme that runs for 2 h in the morning and 2 h in the afternoon. Residents are welcomed into a calm environment with gentle music and the space/room scented with lavender. Ideally Namaste Care has a dedicated room/space, but may also take place in a screened off area, or a dining room otherwise only used at mealtimes. Namaste residents are assessed for pain and discomfort, and treated if necessary. The Namaste Care worker offers personal care as meaningful activity alongside individualised interventions, e.g., rummage boxes, or doll therapy if judged appropriate (24). Fluids are offered frequently during Namaste along with high caloric food treats. The programme is organized every day for 2-h morning and afternoon sessions.

A meeting with family/friends (if this is possible) is a key element of the program and explores specific sources of comfort and pleasure for their relative, creating an individual sensory biography to guide the Namaste Care worker. The discussion provides an opportunity to acknowledge disease progression and establish the goal of a peaceful, dignified death in the familiar surroundings of the care home. This meeting also gives the opportunity to introduce advance care planning in a positive context.

Implementation

In 2012, the researchers approached nine care home managers (all providing nursing care for people with dementia), situated within the five south London boroughs served by St. Christopher’s Hospice, to volunteer to participate in the study. Managers were asked to collaborate in implementing Namaste, while working in partnership to evaluate the programme’s impact. The manager’s willingness to participate was a crucial factor in choosing the study care homes. The researchers looked for diversity in the care homes in relation to the following: size and locality of care homes; provider organizations; previous participation in end-of-life care training (Gold Standards Framework, www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/care-homes-training-programme); and the physical environment.

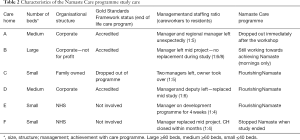

Six out of the nine care home managers approached agreed to collaborate; two care homes were NHS Specialist Care Units with residents with complex behavioral problems (see Table 2). Of those who declined, one CH manager was new in post; another manager was about to leave; a third deemed that Namaste Care might be inappropriate in their specifically Christian organisation. Medical care was provided by general practitioners external to the care home.

Full table

The Namaste program was implemented in each care home and evaluated after 3 months. A one-day workshop (JS & MS) was attended by each care home manager and at least two designated Namaste Care workers from each care home. The Namaste care workers were chosen by their managers because they commanded respect within the care team, based on seniority and/or personality. They were experienced and committed to the care of people with advanced dementia; they tended to be tactile and gentle in their approach to care and they were enthusiastic about involvement with Namaste. The workshop included teaching about advanced dementia, end-of-life care, and outlining the theory and practice of Namaste.

Each manager received two copies of Simard’s book (19), and information about their role in the research. Following this workshop, JS & MS visited each care home for a day, within the same week as the training, holding 20-minutes ‘teaching huddles’ explaining Namaste to as many staff as possible. A further visit the following week included role-modelling a Namaste session.

The care homes received no financial support to fund the implementation of Namaste Care.

Data collection

Staff focus groups were held in each care home before and after the implementation of Namaste and were led by JH & MS. Pre-implementation focus groups were held in each care home, prior to the first Namaste workshop with the nurse managers and Namaste Care workers. The pre-implementation focus groups explored the following topics: staffs’ feelings in relation to caring for people with advanced dementia; relationships with families; and their experience of end-of-life care. Nurses and care workers were invited to join the focus group by their nurse manager and the researchers. Focus groups took place in work time and lasted between 45–60 minutes. Post-Namaste focus groups were held 3 months after a care home started the programme; topics included: care staffs’ experience of Namaste and how it affected them; how Namaste affected the people they cared for and their families; what difference Namaste made to the ways they worked; and the relationships between everyone involved in care.

Monthly collaborative meetings were held with staff and managers during the implementation, collecting data on the challenges and opportunities of implementing Namaste. A reflective diary (MS) kept throughout the process recorded observations, with particular attention to barriers and facilitators of the process of change, alongside insights from meetings with staff and families. A ‘Namaste Book’ was provided, inviting staff and families to record thoughts and feelings about the programme.

Family focus groups were also held in each care home after 3 months of the implementation. Nurse Managers invited relatives/friends of residents enrolled in the study to take part. JH & MS asked participants what they thought was good about Namaste and what they found difficult; how Namaste affected their relationship with staff; their feelings about their relative’s care; and the impact of Namaste on their own quality of life.

Individual semi-structured, face-to-face interviews were conducted with care home managers at the end of the study, exploring changes including a management perspective, i.e., staff responses to Namaste and how Namaste affected the organisation.

Analysis

A qualitative descriptive approach was taken to data analysis, aiming to identify patterns and meaning from the data (25,26). Some grounded theory techniques were used (27,28). The focus groups and the managers’ interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data from the reflective diary (MS) and writings from the Namaste comments books were also typed up and included. Data were grouped and analysed on a per care home basis at first. Transcripts were read and re-read, to ensure familiarity; recurring words, phrases and concepts were highlighted in order to develop codes [an umbrella term for groups of concepts (29)]. An initial list of codes was developed from the first transcript, and this was applied to the analysis of the second transcript. When new concepts emerged from analysis of the second transcript they were added to a revised coding framework. The first transcript was then recoded using the revised framework, and the process repeated throughout all transcripts, with the coding being repeatedly revised. Finally, data were compared across the care homes; similar and related codes were organized into higher level categories, which were restructured into themes to form a coherent whole. MS and JH engaged in a re-iterant process of discussing areas of agreement and disagreement to enhance analytical rigour and achieve consensus.

Ethical approval was granted by the East Anglia Research Ethics Committee and the South London and Maudsley Foundation Hospital Trust NHS Research and Development Committee (12/EE/0010). Care home managers and senior managers signed gate-keeper consent, while staff and families signed individual consent at the beginning of each focus group. Residents who met the inclusion criteria—a dementia diagnosis and score >16 on the Bedford Alzheimer’s Nursing Severity Scale (30) —were identified by the nurse managers who then assessed his/her capacity to give informed consent to participate in the study. Where residents lacked capacity to give informed consent, the decision whether they should participate was guided by the consultee process established by the Mental Capacity Act (31). A family member was invited to represent the resident as a ‘family consultee’, and advise the researchers on the basis of the person’s known views and the consultee’s sense of how the person’s values would influence the decision. In the absence of a family member, a professional, not directly involved in the research, was nominated to act as ‘professional consultee’ for a resident. The decision whether to include a resident in the study was made on the basis of the person’s best interests, with the consultee advising the researchers. Where a resident entered the study, the consultee was able to withdraw the resident’s participation at any point. Process consent from residents was negotiated on a day-to-day basis. A protocol was in place should the study uncover poor practice.

Results

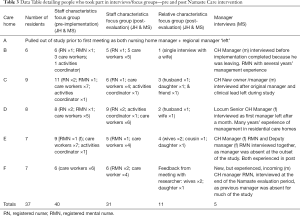

Out of the six care homes who agreed to take part, CH A had to withdraw at the outset of the study because both the manager and regional manager left unexpectedly. All of the remaining five CHs experienced significant management disruption during the research. By the end of the implementation period four CHs were achieving the full Namaste programme with two sessions each day; another worked more slowly and continued to run the programme every morning with only occasional afternoon sessions. Four CHs remained committed to Namaste but the 5th CH discontinued the programme when research involvement ended. The two CHs that struggled with implementing Namaste had very unstable management; in one the manager was not replaced during the course of the study and in the other, the manager was replaced and staff learned the unit was to close down. There was only one negative response to Namaste from a family member; a daughter who felt her mother was too tired to attend two sessions per day. Table 3 presents a summary of those who attended focus groups and interviews.

Full table

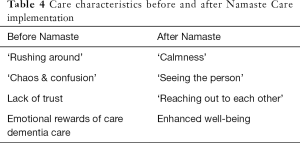

The qualitative analysis is presented to illustrate the changes in the behavior of care staff towards people with advanced dementia following the implementation of Namaste, and the effects upon residents, families and staff (see Table 4).

Full table

Perceptions of care before implementing Namaste

Four themes emerged from the pre-Namaste focus groups and the researcher’s observations: ‘rushing around’; ‘chaos and confusion’; the emotional rewards of dementia care; and ‘lack of trust’.

‘Rushing around’

In all the CHs, care staff worked under pressure with a heavy workload. Almost all residents were extremely frail–many were dependent for all activities of daily living with some resistive to care and requiring two care workers to help them. Care workers were not only responsible for residents’ personal care but also for housekeeping jobs such as filling water jugs/sorting laundry.

“In the morning, you just rush for about 19 highly dependent residents, we have only three carers with one nurse. The nurse will be doing medication, the carers will be rushing, to wash them and clean them, at least wash their face, clean them so at least they can eat breakfast. So you see them rushing, you see everybody sweating” (CH.B pre-Namaste staff FG).

Before implementing Namaste, there appeared to be a troubling tension for care workers between pressure to complete priority tasks and the desire to respond to residents’ needs for company and comfort.

“After she said, ‘Please can you stay with me’, I said, ‘Sorry I can’t stay with you, we have other patients and things to do’. She needs us to be there for her, the time wasn’t there for us” (CH.B pre-Namaste staff FG).

Care workers were allocated the task of ‘watching over’ residents in the lounge to prevent falls and ‘incidents’. The television was usually on, but rarely watched. Paradoxically, although staff reported wanting to spend more time with residents, there was less interaction between care workers and residents during this ‘empty’ time than during physical care.

‘Chaos and confusion’

The behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia are a common feature of dementia in CHs where the social and physical environment often triggers distressed and inappropriate behavior. Asked what they found hardest about caring for people with advanced dementia, one care worker instantly responded “aggression”; this particular CH had a designated ‘challenging behavior floor’. A care worker from a different CH painted a vivid picture: “So the music is playing, and we have got a person out in the garden who is looking at his reflection in the glass and dancing. And he’s really happy with the music. And we have got another person who hears the music and hates it and wants it off. So we have got all these mixtures of people’s emotions in one room. It becomes quite chaotic and confusing” (CH F pre-Namaste staff FG).

This sense of chaos and confusion was reinforced by family members’ descriptions of visiting. In relation to this sense of chaos, two family members spoke of the CHs as ‘another world’; one sometimes felt she couldn’t face visiting because other residents had stripped naked and been violent at times.

The emotional rewards of dementia care

Interestingly, care staff in all pre-Namaste focus groups described using their skills to meet the challenges of dementia care as rewarding: “I find it really rewarding to do. It’s nice when you achieve something. If a person, you know, has been… maybe has got aggression that you actually manage to get them calmer and manage to get them showered… and make them look nice” (CH.D pre-Namaste FG).

In every focus group, care staff spoke of ‘feeling good’, and ‘their work making them happy’. Many related the experience of caring for residents to caring for their own parents, some identified with residents themselves.

Lack of trust

Sometimes there appeared to be a lack of trust within the CHs between care staff and management, nurses and care workers, which extended to relations with families and GPs. In one pre-Namaste focus group a nurse suggested that the ethnic and cultural diversity of their group threatened teamwork.

“…we are people from different cultures, different backgrounds, we all not think alike, we don’t always speak the same way… We’ve got to give and take, and listen very carefully. The important thing like (name of care worker) said, ‘the resident we are here for’ - the main objective is our resident” (CH.C pre-Namaste staff FG).

During the study, we learned that divisions and communication difficulties between nurses and care staff were present to varying extents in all CHs. Many staff felt that residents were the sole focus of care. Consequently, involving families with end-of-life care was often seen as a complication and the family was perceived as being ‘in the way’.

“I find this (involving families in end-of-life care) very challenging. The families… I will say, only about 1% of the family do understand and do co-operate with the staff especially on the dementia unit. About 90% of the relatives, they don’t cooperate at all… They always come and find faults. They always come in with questions, no matter what you do” (CH.B pre-Namaste staff FG).

This lack of relationship and trust extended to the inter-professional team.

Perceptions of care following the implementation of the Namaste Care program

Four of the five CH managers spoke about ‘embracing’ Namaste. This response reflects the value they set on the programme and the emotional nature of the changes brought about by Namaste in these committed CHs.

Four over-arching themes emerged from the analysis (see Table 4).

Calmness—‘Namaste is a feeling’

Many staff and relatives spoke about the calmness that Namaste brought to the CH.

“And I felt a sense of ‘oh, where am I? …This is lovely!’ You know what I mean? It really hit me as I walked through the door …The feeling of relaxation and everyone is quiet… these are the people who are usually outside and usually standing up shouting—there’s one singing. They were all quiet” (CH.E family FG).

All four committed CHs noticed the reduction in behavioral symptoms in their residents, which was confirmed by the quantitative data (18). One man who cried continuously was comforted and became less tearful; another showed a marked reduction in disinhibited behavior; people who usually refused to sit with others joined the Namaste group. Care staff, relatives and the researcher observed that the changes seen in the behavior of residents with advanced dementia were not confined to the Namaste room, but also affected the wider care home environment.

“…Before they were pacing around and would not even sit down for a second… the fact is that they are sitting down now. And I, myself, am not constantly checking to see when they are going to stand up… it is not as hectic as it was before” (CH.D post-Namaste staff FG).

The deliberate serenity of the environment, coupled with the loving touch approach, slowed the pace of interaction and made more one-to-one time, enabling staff to engage with residents. The changed routine meant that care workers who had previously been ‘just watching’ residents in the lounge, were now busy with the Namaste schedule.

Seeing the person

In four CHs, Namaste reshaped the routine towards a more person-centred approach, with care staff developing increased respect for the dignity of residents—seeing them as people.

“…you can very easily get caught up in toileting and helping to eat and all of those things and not see the person sometimes. I think this has brought that out” (CH.C Manager’s interview).

Care workers were less driven by ‘doing for’, instead there was a greater sense of ‘being with’ residents. The hours Namaste Care workers spent interacting with residents with advanced dementia brought greater recognition that these people could actively engage and were not passive recipients of care.

“Because we know we’ve got a slot for Namaste, rather than doing something else, we’re there with our residents, engaging. We get to do massage, we get to give them their little treats, their fruits… Their hair… we’ve got that time with them, we can do all these, make them nice. It gives them more time to engage back to you rather than, in the morning, when we are getting them washed and dressed, you’re rushing. You have no time to spend with them. That slot, Namaste slot, is time to engage with them, and to spend more time with them” (CH.B post-Namaste staff FG).

We found that Namaste could change how staff felt about their work. One manager spoke about a care worker who one week before starting Namaste wanted to hand in her notice.

“She said, ‘You know what (manager’s name) thank you so much for that… for to do the Namaste. It gives me a sense of worth.’ She said, ‘I feel as if my work here has more meaning, and I don’t care about what other people think now’ ” (Managers’ interview CH.E).

In one CH it was difficult to get full commitment. Namaste was seen as an additional, burdensome task. The newly appointed manager observed that the task-orientated approach and the emphasis on ‘getting things done’ were aspects of a wider dysfunctional culture of the CH that militated against establishing the more person-centred, relationship-based care that Namaste supports.

However, in the committed CHs, the enhanced sense of respect for residents’ privacy and dignity, generated by the programme, flowed into care when people were dying.

“…when she was near to the end, you know, we took her to her room and brought the music box into the room. I remember she used to like Nat King Cole. And I had put that music on… she was very near to the end… and she held up her head, opened her eyes and smiled…” (CH.C post-Namaste staff FG).

Reaching out to each other

When asked to articulate the purpose of the programme, a care worker wrote, ‘to enable us to reach out to each other’. This theme of connection, re-connection and shared humanity is the foundation of the relationship-based care that Namaste fosters. Many care staff and families talked about the emotional significance and power of touch. Namaste gave people (care staff and families) permission to touch residents that seemed to be a catalyst for change.

“…there’s health and safety, you can’t do this, you can’t do that. In fact, if you walked into a lounge, would you feel quite so at ease if somebody was sitting stroking my husband’s arm? …But by… being straightforward and saying, ‘This is what we’re doing’. Immediately it’s got a legitimacy. And if they didn’t have that, kind as the people are, there would be no tactile touching and stroking” (Family FG CH.E).

An important principle of Namaste is that gloves are not worn when there is no medical indication. Wearing gloves was embedded in CH routines, and care workers instinctively understood that taking off their gloves when touching residents symbolized a different way of working, removing a barrier between themselves and the people they cared for.

Care worker 1: “…we are doing it without gloves so they feel our body, our warm body. So the experience and feeling is totally different.”

Care worker 2: “…Intimate. Intimate rather than with gloves, you know, because the gloves is between our skin and their skin. But now we touching them, body contact together, you know, they feel our warmness, we have to feel their own warmness …They will know someone is touching them” (CH.B post-Namaste FG).

Many residents with whom there had previously been minimal communication became more responsive when they received intentional ‘loving touch’ rather than the functional touch of personal hygiene. Some profoundly disabled residents began to respond actively, making more eye contact, smiling more and trying to communicate verbally. Families also re-connected with their relatives. One lady, whose daughter was rubbing lotion into her hand, massaged her daughter’s hand back. Her daughter tearfully explained that her mother had not done anything motherly for years.

“And you get that relationship… touch builds a relationship between people doesn’t it? …So in that moment there is a really good bond between the staff and the resident” (manager’s interview CH.C).

Relatives recognised the compassion of care staff and appreciated the difficulties of caring for people with advanced dementia.

“They are doing what they have to do for the patients. But suddenly this is another dimension isn’t it? …It appeals to their inner kindness too. If you see that you are giving someone pleasure, you have to be a very cold human being not to be touched by that” (CH.D Family FG).

Enhanced well-being

Relatives and staff perceived a greater sense of well-being in residents. The changes seen in residents who were lethargic and unresponsive were as remarkable as changes from agitation to calmness.

“…I think it has been wonderful. She is much more healthy now. I don’t know why, but she is different. She is more alive even though she can’t do anything for herself at all” (CH.C Family post-Namaste FG).

“…they are lighting up and they look well. To look at them, they really look well. Even very ill patients are looking much better” (CH.D post Namaste staff FG).

Sensory stimulation seemed to create a new sense of self-awareness in some residents. One lady stroked her face after moisturiser had been gently applied, which had never been observed before. A man who was deeply resistive to personal care washed his hair while in the bath—perhaps experiencing a re-awakened awareness of his body. Residents with hearing or sight loss were particularly responsive to sensory stimulation in Namaste.

Just as residents appeared calmer, staff also found that slowing down, listening to music, the scent of lavender, and skin to skin contact affected their own mood and behavior.

“…because of the music or the sound effects, you relax as well. I would say that it does it for me as well, even for 10 minutes, it can actually just keep me at a calmer level. Even if I was stressed earlier on in the morning, or something, it does actually help” (CH.D post-Namaste staff FG).

For one wife, the guilt she felt for placing her husband in the CH and leaving him each day after visiting was lifted. A daughter summarized the impact of Namaste.

“The biggest thing Namaste has given me is a different focus when visiting mum. For many years now mum hasn’t been able to communicate with us and conversation has been one sided which is difficult and at times she appeared to barely realize I was there. I now know to do other things as well as talk to mum like show her old photos, brush her hair, feed her treats, and moisturise her face and hands. This makes spending time with her easier and I feel I’m making more of a connection with her and a difference in her life” (CH.D email—family member).

Namaste made visits easier, helped her re-connect with her mother and recover a meaningful role in her mother’s life.

Discussion

This study is the first to evaluate Namaste Care in the UK, and showed that with good leadership in place it was possible to implement the program with only modest expenditure and no change in staffing levels. However, where leadership was weak or absent it was more difficult: one care home did not achieve the full program, and in another the program was discontinued when the study ended. The quantitative results of the study demonstrated that Namaste achieved a reduction in the frequency and severity of behavioral symptoms in people with advanced dementia (21). The qualitative findings show that the improvements in well-being described by participants were not limited to care home residents, the benefits of Namaste extended to relatives and staff, and included a positive influence on the care home culture.

In a review of leadership in healthcare, West et al. (32) conclude that leadership is the most influential factor influencing organisational culture in health care, and found clear evidence of links between leadership and overall quality of care. A systematic review of staff training interventions to reduce behavioral symptoms of dementia (33) found the success of interventions was very dependent on organisational factors such as management, care culture and rifts between staff groups. It is not surprising that Namaste floundered where leadership was weak.

Many psycho-social and sensory interventions are effective in reducing agitation for people with dementia (18,34), but the evidence is for short term effect during the intervention, with little or no lasting effect (35). Namaste overcomes this short-lived effectiveness by scheduling the programme: seven days a week, morning and afternoon. Schreiner et al. report that residents with dementia expressed happiness over seven times more often during structured recreational time than during unstructured time (36). Namaste imposes structure on “empty time” when residents with advanced dementia are not engaged in personal care or mealtimes, and empowers care staff to connect with residents, engaging them in meaningful activity.

Our study confirmed touch as a powerful element of Namaste, which accords with Cohen-Mansfield’s (35) findings regarding the potency of one-to-one interaction as a stimulus to engaging people with advanced dementia. Similar findings are reported from an Australian study of Namaste (37) which describes the mutuality of the experience of touch and the benefits shared with care staff and families. Their theme of ‘interconnectedness’, and our echoing theme of ‘reaching out to each other’, highlight the potential of Namaste to support relationship-based care (38-40), and imbue everyday care with significance for people with advanced dementia.

Kontos (41) addresses the concept of selfhood in relation to advanced dementia, positing selfhood as an ‘embodied dimension of human existence’, and recognizing smiles, frowns and gestures as subtle forms of self-expression arising from a lifetime of social interaction and carrying meaning. Personal care (i.e., grooming) is not the prerogative of the sick and disabled, but a daily routine undertaken by people everywhere and an elemental part of well-being. Watson (42) suggests that care for people with advanced dementia should recognize physical care, not as a task, but as a way of valuing and respecting the person, an opportunity to recognize and support their embodied self and a means of forming or maintaining a relationship. There was evidence within this study that Namaste is a practical application of this concept.

Person-centred care is recommended by national guidelines (14), and accepted as fundamental to achieving good quality of life and care for people with dementia. Kitwood’s principles of person-centred care (15) assert the human value of people with dementia and those who care for them; the uniqueness of each individual affected by dementia; the importance of seeing from the perspective of the person with dementia; and the importance of relationships and interactions with others. The Care Worker who wrote that the value of Namaste is ‘to enable us to reach out to each other’ captures the essence of person-centred care. ‘Reaching out’ has a literal and metaphorical meaning; it suggests physical touch, but also social, emotional, and spiritual connection between the person caring and the person with dementia. The philosophy of person-centred care usually puts little emphasis on the body: but Namaste redresses the balance and provides a practical, embodied translation of Kitwood’s principles.

Namaste challenges normal routinised care for older people with advanced dementia in care homes and provides an alternative structure of care that delivers repeated opportunities for interaction and engagement, alongside increased hydration and nutrition, and a focus on comfort, including pain management. The structured approach of the Namaste Care programme supports care staff to meet the social, emotional, physical and spiritual needs of residents with advanced dementia, and to enrich their quality of life.

A common criticism of ‘programs’ or ‘activities’ that can help staff see the person and connect is that they create ‘person-centred moments’ rather than person-centred cultures (43). If the activity or program is seen as something that only happens in a particular place (e.g., a Namaste room) or with a particular person (e.g., a Namaste carer) rather than becoming embedded in everyday care, then the potential for improving quality of life and quality of care is less. There was some evidence from the study that Namaste became embedded, for example, the manager’s comment that, ‘Namaste is like lunch’, and the frequent observations that the care homes were calmer. Working with Namaste, care staff learned to change their behavior towards residents with advanced dementia: slowing down; giving the resident undivided attention; and using touch and the other senses to communicate. It seems that sometimes these changes were sustained and carried into every day care, but no measures were in place to capture this, and the extent to which the culture of care was changed in each care home is unclear. This would be an important point to factor into further research.

There were several limitations to this study. Action research is small scale and unashamedly participative. The researchers undertook the workshops, worked with the care homes, conducted the interviews and focus groups, and then analysed the resulting data. This may have introduced elements of bias to the findings despite the researcher’s critical stance. Also, participants may have sought to please the interviewers despite being asked to be totally objective in the post-implementation focus groups. On the other hand, the researchers’ involvement in the implementation process provided insights, supplied context, and amplified the learning from the focus groups and interviews.

This feasibility study of Namaste should now be exposed to further research. This might include investigating the different elements of Namaste Care, and reviewing the best way to implement the care program.

Conclusions

Namaste created an alternative structure for compassionate and dignified care that supported person-centred, relationship-based care in care homes; enriched the quality of life of older people with advanced dementia; and had a positive impact on their families and the staff who cared for them. This study demonstrates the continued ability of people with advanced dementia to engage in positive ways and Namaste Care provides a way of enabling this in the day to day life of a care home. Namaste Care deserves to be tested in a randomised controlled trial, and if these findings are borne out, then the care programme should be included in National Guidelines for the care of older people with advanced dementia.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the managers of each care home and their staff for agreeing to take part in researching the process of implementing Namaste. In particular we would like to thank the relatives/friends/professionals who acted as consultees for those residents taking part. We would like to thank the members of our steering group for their advice and support. This work was supported by St Christopher’s Hospice.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by the East Anglia Research Ethics Committee and the South London and Maudsley Foundation Hospital Trust NHS Research and Development Committee (12/EE/0010).

References

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. Dementia statistics. 2015. Available online: http://www.alz.co.uk/research/statistics

- Volicer L, Simard J, Pupa JH, et al. Effects of continuous activity programming on behavioral symptoms of dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2006;7:426-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brooker DJ, Woolley RJ. Enriching opportunities for people living with dementia: the development of a blueprint for a sustainable activity-based model. Aging Ment Health 2007;11:371-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moniz-Cook E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Woods R, et al. A European consensus on outcome measures for psychosocial intervention research in dementia care. Aging Ment Health 2008;12:14-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ 2015;350:h369. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borsje P, Wetzels RB, Lucassen PL, et al. The course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in community-dwelling patients with dementia: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr 2015;27:385-405. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. Palliat Med 2014;28:197-209. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sampson EL, Thuné-Boyle I, Kukkastenvehmas R, et al. Palliative care in advanced dementia; A mixed methods approach for the development of a complex intervention. BMC Palliat Care 2008;7:8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pace V, Treloar A, Scott S. Dementia: from advanced disease to bereavement. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Hughes J, Lloyd-Williams M, Sachs G. Characterising care. In: Hughes J, Lloyd-Williams M, Sachs G. editors. Supportive Care for the Person with Dementia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Jethwa KD, Onalaja O. Advance care planning and palliative medicine in advanced dementia: a literature review. BJPsych Bull 2015;39:74-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer’s Society. Low expectations: Attitudes on choice, care and community for people with dementia in care homes. 2013. Available online: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/download/downloads/id/1705/alzheimers_society_low_expectations_executive_summary.pdf

- Alzheimer’s Society. Home from Home. A report highlighting opportunities for improving standards of dementia care in care homes. 2007. Available online: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/download/downloads/id/270/home_from_home_full_report.pdf

- NICE. Dementia: Supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. 2006. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg42/chapter/person-centred-care

- Kitwood T. Dementia Reconsidered: the person comes first. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1997.

- Banerjee S, Samsi K, Petrie CD, et al. What do we know about quality of life in dementia? A review of the emerging evidence on the predictive and explanatory value of disease specific measures of health related quality of life in people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;24:15-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alzheimer’s Society. ‘My name is not dementia’: people with dementia discuss quality of life indicators. 2010. Available online: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?downloadID=418

- Livingston G, Kelly L, Lewis-Holmes E, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for agitation in dementia: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Psychiatry 2014;205:436-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simard J. The End-of-Life Namaste Care Programme for People with Dementia. Baltimore: Health Professions Press, 2007.

- Simard J. The End-of-Life Namaste Care Programme for People with Dementia. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Health Professions Press, 2013.

- Stacpoole M, Hockley J, Thompsell A, et al. The Namaste Care programme can reduce behavioural symptoms in care home residents with advanced dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2015;30:702-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hart E, Bond M. Making sense of action research through the use of a typology. J Adv Nurs 1996;23:152-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simard J, Volicer L. Effects of Namaste Care on residents who do not benefit from usual activities. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2010;25:46-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mitchell G, McCormack B, McCance T. Therapeutic use of dolls for people living with dementia: A critical review of the literature. Dementia (London) 2016;15:976-1001. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pope C, Mays N. Qualitative Research in Health Care. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 2006.

- Vaismoradi M, Turunen H, Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci 2013;15:398-405. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health 2000;23:334-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. London: Sage Publications, 2008.

- Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. 2nd. London: Sage, 2009.

- Volicer L, Hurley AC, Lathi DC, et al. Measurement of severity in advanced Alzheimer's disease. J Gerontol 1994;49:M223-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Department of Health. Guidance on nominating a consultee for research involving adults who lack capacity to consent. 2008. Available online: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_083131

- West M, Armit K, Loewenthal L, et al. Leadership and Leadership Development in Healthcare: The Evidence Base. London: Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management, Faculty of Leadership in Medicine, Kings Fund, Centre for Creative Leadership. Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/leadership-leadership-development-health-care-feb-2015.pdf

- Spector A, Orrell M, Goyder J. A systematic review of staff training interventions to reduce the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Ageing Res Rev 2013;12:354-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lawrence V, Fossey J, Ballard C, et al. Improving quality of life for people with dementia in care homes: making psychosocial interventions work. Br J Psychiatry 2012;201:344-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Marx MS, Dakheel-Ali M, et al. Can agitated behavior of nursing home residents with dementia be prevented with the use of standardized stimuli? J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:1459-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schreiner AS, Yamamoto E, Shiotani H. Positive affect among nursing home residents with Alzheimer's dementia: the effect of recreational activity. Aging Ment Health 2005;9:129-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nicholls D, Chang E, Johnson A, et al. Touch, the essence of caring for people with end-stage dementia: a mental health perspective in Namaste Care. Aging Ment Health 2013;17:571-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koloroutis M. Relationship-based care. Minneapolis: Creative Health Care Management, 2004.

- Nolan MR, Davies S, Brown J, et al. Beyond person-centred care: a new vision for gerontological nursing. J Clin Nurs 2004;13:45-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wilson CB, Davies S. Developing relationships in long term care environments: the contribution of staff. J Clin Nurs 2009;18:1746-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kontos PC. Ethnographic reflections on selfhood, embodiment and Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Soc 2004;24:829-49. [Crossref]

- Watson J. Developing the Senses Framework to support relationship-centred care for people with advanced dementia until the end of life in care homes. Dementia (London) 2016. [Epub ahead of print].

- McCormack B, Dewing J, McCance T. Developing person-centred care: addressing contextual challenges through practice development. Online J Issues Nurs 2011;16:3. [PubMed]