Life perceptions of patients receiving palliative care and experiencing psycho-social-spiritual healing

Introduction

In 1961, Dame Cicely Saunders, the founder of the modern hospice movement (1), wrote a detailed and poignant account of a patient from time of hospital admission to death (2). In this field-defining paper, Saunders personified palliative care as she wrote not of medical interventions but rather focused mainly on one patient’s journey in spiritually conquering her illness. The narrative centered on how the patient’s relationship with her family, the hospital staff, and the chaplain helped her overcome both physical and emotional suffering. In the past few years, there has been burgeoning literature studying patient and caregiver experience, particularly relating to palliative care. Several recent studies have examined patients’ perceptions of the quality of palliative care and patient-clinician communication, using questionnaire-based instruments (3-5). Through a study using qualitative grounded theory approach, Hannon and colleagues also demonstrated the value of patient and caregiver perspectives for promoting early palliative care and guiding future healthcare models (6).

The Pain and Palliative Care Service (PPCS) was established at the Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health in August 2000 with the commitment to practice patient-centered and family-oriented care as an interdisciplinary team while integrating clinical expertise with research (7). Since then, PPCS has dedicated its team and resources to providing comprehensive care that addresses the physical, psycho-social, and spiritual needs of patients and families affected by life-threatening illness. Instead of only treating the “patient with the disease”, palliative care as a medical specialty strives to treat the person behind the patient and to better understand individual perceptions of healing. In her article “A Patient” Dame Saunders wrote, “it is really impossible to show how much we have all learned through her; I can only try to underline the things that brought her through and made her so triumphant.” In this study, by directly asking patients about their personal strengths, struggles, and experiences with palliative care, we hoped to better understand the psycho-social-spiritual constituents of healing and how patients begin to overcome their illnesses.

Methods

Study design

This study was conducted as a qualitative component of the larger study, which was the content analysis of the HEALS (Healing Experience during All Life Stressors) instrument through cognitive interviewing. Patients receiving care from the PPCS team were actively recruited from January through June 2016. Eligible patients were at least 18 years of age with a life-threatening illness, 91 days post-diagnosis, English-speaking, and receiving palliative care at one of the following three locations: (I) inpatient and outpatient services at the NIH Clinical Center, a research hospital; (II) inpatient service at Johns Hopkins Suburban Hospital, a community hospital, or (III) Mobile Medical Care Inc. (MobileMed), a community-based clinic for low-income patients, where specialty pain and palliative care consultation was provided bimonthly by the NIH PPCS team (8).

All patients identified as potential participants by a palliative care specialist received an information packet with a copy of the informed consent and participated in in-person meetings with a member of the research staff. Of a total of 56 eligible patients (43 from NIH Clinical Center, 8 from Suburban, and 5 from MobileMed), a purposive sample of 30 participants were enrolled in the study. Half of our participants had a known diagnosis of cancer. The most common reason for non-participation was the patient not feeling well enough for in-person interviews at the time. The Institutional Review Boards at NIH and Johns Hopkins (for Suburban Hospital) approved all study procedures.

Interviewer-administered questionnaires

The following open-ended questions were created by the current research team and used to evaluate factors that may contribute to the healing process: (I) what does the word “healing” mean to you? (II) how did circumstances or previous life experiences help prepare you to handle your illness? (III) in what ways were you unprepared? (IV) what problems or barriers come up as you follow through on recommendations provided by the Palliative Care service? (V) what part of the Palliative Care program has been most helpful to you? And how has that been helpful? Questions 2 through 4 will be the focus of this manuscript.

To further assess barriers to palliative care and potential healing, questions were adapted from the Needs Assessment Questionnaire published in a study by Lyckholm and colleagues (9). The 24-item interviewer-administered questionnaire consisted of 5 general categories: (I) patient risk factors; (II) caregiver; (III) living conditions; (IV) transportation, and (V) knowledge/planning. For the purpose of this study, participants were asked to respond “yes” or “no” to each item. The two items on immigration status and mental health history from the original questionnaire were not asked due to the sensitive nature of the questions.

Data collection

Verbal and written informed consents were obtained from all participants. Prior to the first interview, a pilot session (not included in the analysis) was held to validate the research instruments and study protocol. All interview sessions were audio-recorded and conducted in-person in a private location (hospital room or outpatient exam room). A written script using probe questions derived from the cognitive interviewing approach was followed (10). The duration of each interview varied from 21 minutes to 1.5 hours (mean time =43 minutes). Data on demographic variables and religious affiliations were completed by the participants themselves.

Data analysis

All audio recordings from the open-ended questions were transcribed within 24 hours of the interview. An interdisciplinary team (physicians, registered nurses, and researchers) conducted the initial review of the data and established a preliminary analytical framework. Based on a list of first-level codes used to identify and classify the phrases item-by-item, three members of the study team independently proceeded to perform a second-level coding of unique participant responses. Major and minor themes were then derived from each open-ended question that best reflected the participants’ life experiences.

Results

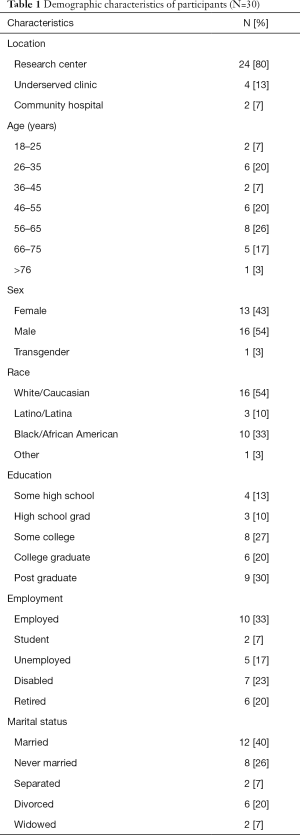

Of the 30 participants, 24 (80%) were receiving inpatient or outpatient palliative care at the NIH clinical center. Thirteen (43%) participants were female, 1 (3%) identified herself as transgender, 16 (54%) were White/Caucasian, and 10 (33%) were Black/African American. More than half of the participants were younger than 55 years and 7 (23%) were unemployed due to a physical disability. A summary of the demographic characteristics of the study cohort is provided in Table 1.

Full table

Responses to the Needs Assessment Questionnaire developed by Lyckholm and colleagues (9) showed that 5 (17%) of our participants did not have medical insurance, 4 (13%) reported being homeless, or “unhoused” (without a stable living environment), and 12 (40%) stayed mostly in bed during waking hours due to their illness. Whereas half of our participants had caregivers, eight (27%) also reported being a caregiver for someone else. In regards to living conditions, 2 (7%) participants considered their neighborhood unsafe, 9 (30%) received food stamps, and 7 (23%) lived in a rural location. Nineteen (63%) patients had a living will or advance directive while 23 (77%) said they were familiar with hospice care.

Previous life experiences

When asked how past circumstances or previous experiences in their lives had prepared them for the illness, many participants mentioned that memories of someone else’s experience in dealing with a serious illness helped shape their own coping strategies, and the type of individuals they became after being diagnosed with a life-threatening illness. These reports reflected a “role model” theme (Table 2). Others spoke of previous occupations and professional roles (“Occupational Role” theme). For example, one participant shared how being a physician and caring for others with serious illnesses later helped him take on the patient role:

Full table

“And I have dealt with death and dying multiple different ways… so when mine came up… it was my turn to get on the merry-go-around… take a bunch of tests and such.”

Further, some participants viewed “Previous Experiences” as a supportive network built from connections with their loved ones, religious community, or directly through a Higher Power, as shown here:

“If God wants to take me now… that’s fine because I’m going to be okay and great. And if God blesses me to be on earth a little longer to be with my family then I’m going to be okay there. So either way, I am gonna be okay.”

The above quote can also represent the theme “Inner Strength” that emerged from acceptance of the illness or situation. This concept is further reflected in statements that expressed the participants’ determination to fight their diseases, to pursue life to the fullest, and to not let their illness overshadow the good things in life because the reality of their diagnosis could not be ignored or changed.

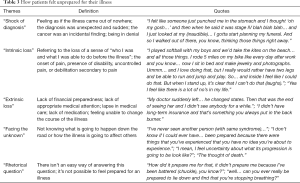

In contrast, concerning the topic of how patients felt unprepared for their illness, many participants’ past life experiences were filled with memories of a sense of shock and loss associated with their illnesses (Table 3). When recalling what made them feel unprepared, most patients reported that the diagnosis came suddenly and unexpectedly, such as the incidental finding of cancer during a routine check-up. One participant said:

Full table

“I am the last person I thought would ever have cancer.(chuckle)…I had no risk factors, I… was physically very active, had a great diet. I was shocked and numb for a very long time and really in disbelief for a very long time… I even didn’t believe that when they were going to go in and do surgery, they were actually going to find that it’s going to be cancer… I was completely unprepared.”

The initial “shock of diagnosis” was often followed by a sense of loss that can be characterized as “intrinsic” or “extrinsic”. Intrinsic loss may manifest physically and emotionally at the onset of uncontrollable pain or physical debilitation such as “being thrust into a wheelchair overnight.” On the other hand, extrinsic loss may be caused by loss of financial stability or lack of appropriate medical resources and treatment options. The theme of “facing the unknown” referred to the uncertainty of their prognosis and thoughts of death and dying. Furthermore, when asked about how they were unprepared for their illness, several participants regarded it as a “rhetorical question” by responding: “Well, who wants to be sick?”

Perception of barriers

While five participants denied any barriers to palliative care, others experienced financial limitations and gaps in access to treatment that made it difficult for them to follow through on recommendations provided by palliative care services (Table 4). Four participants from the Clinical Center said that their barriers were due to difficulties obtaining similar palliative care intervention (i.e., reiki, acupuncture, tai-chi, massage therapy) outside of the NIH. There were also “symptom barriers” characterized by the inability to go to clinic appointments due to pain or other physical limitations. Additionally, many participants expressed a sense of “internal barrier” that triggered self-blame and hopelessness, which subsequently made the recovery process even more challenging. At MobileMed, one of our participants who was homeless described his barriers as the following:

Full table

“I… with my situation, umm… I… was probably a bad patient to start out with. I didn’t have insurance at the time either. I just kept putting it off and putting it off… putting it off you know until finally the pain was… to such a level and I’ve been in pain for so long. Without a diagnosis, I was only getting my pres…prescription strength of ibuprofen and things like that. It’s hard enough for me to stay… you know, away and out of sight you know… so that I’m not bothered by the police or property management.”

Experience with the pain and palliative care team

As a part of the open-ended questionnaire, we also asked what part of the palliative care program has been most beneficial to the participants, and how it has been helpful to them. Regarding benefits of palliative care, the three themes that emerged were (I) “medical management of pain and symptoms” through medication adjustments; (II) “interventions that provided mind-body balance” such as reiki, acupuncture, biofeedback, art therapy, yoga, and music therapy, and (III) “being heard/seen”, which was also the most common response (Table 5). Many participants felt that the palliative care team listened to their stories and recognized their needs. The participant who was homeless said,

Full table

“They (palliative care team) really care and pay attention as to what’s going on with me… they give me their input and they… they also respond to my input. They’re very … very caring, supportive people. I feel like I’m… genuinely actually loved up here. Everybody here would treat their family the way they treat me.”

The theme of “being seen/heard” was prominent and related to participants’ perception of being treated as a whole and respected as the person behind the patient and as a part of the healthcare team. More specifically, many felt supported through “compassionate care” that enabled them to regain their sense of self. For example, one participant spoke about his interactions with the palliative care team:

“They definitely catered to… to my needs as far as they ask me what I want… and kinda… try to streamline to me… I just felt like it was custom-made and we were having a conversation.”

The benefits of palliative care as provided by the medical team were further depicted as “a part of the healing process” and “much more than just getting pain meds.”

Discussion

This manuscript is, to our knowledge, the first to describe how previous experiences in life shaped the way palliative care patients face their illnesses. By definition, palliative care as a medical specialty addresses physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs of patients and their families thereby improving quality of life along the continuum of illness (11). The conceptual themes that were derived from patients’ previous life experiences as well as perceived barriers and benefits of palliative care helped determine the psycho-social-spiritual constructs that take place during the healing process. Our study illustrates the importance of knowing the person behind the patient while recognizing the limitations to palliative care beyond what healthcare providers may perceive as barriers.

Our participants’ accounts of their previous life experiences shed insight into how patients learn to accept and overcome a life-threatening illness. Additionally, we place particular emphasis on the lives and representations of whom patients were before they became ill. In her article, Saunders wrote, “the spirit is more than the body which contains it” (2). In light of their diagnosis, participants demonstrated resilience found through inner strength, spiritual beliefs, or interactions with another individual. This progression through psychosocial and spiritual self-care to reduce suffering has been referred to as a “life-transforming change,” or healing in existing literature (12).

Our results also demonstrated that patients may feel prepared for one aspect of their illness but unprepared for others. The feeling of unpreparedness as interpreted from the quotes reflect the concept of “total pain”, which was first introduced by Saunders to characterize the physical, emotional, social, and spiritual dimensions of distress (2). In addition to processing the diagnosis itself, patients carry the burden of multiple forms of loss in their lives, which adds to their total suffering. In the context of a serious illness, patients may experience psychosocial and spiritual suffering in addition to physical pain and debilitation. For some individuals, the fear of death and uncertainty of their prognosis may contribute to a sense of helplessness and thus hinder their steps towards healing. In fact, some participants mentioned that they felt unprepared for their illness, despite feeling supported through previous life experiences. It is important for healthcare providers to be sensitive to both extrinsic and intrinsic causes of suffering in order to provide comprehensive care for patients and families.

The potential to heal the whole person also depends on the ability of the providers to recognize barriers to treatment by asking the right questions that take into account psycho-social-spiritual considerations. In a study investigating barriers to effective palliative care for low-income patients in late stages of cancer, Lyckholm and colleagues developed a “risk/needs assessment questionnaire” as a method for healthcare providers to better understand patient’s perceptions of barriers to optimal health care (9). Their list of questions was meant to assist physicians to “take a virtual walk in their patients’ shoes” and to begin a conversation with patients and caregivers about how to overcome obstacles to medical care. Our study adapted the needs assessment questionnaire with the intention of identifying barriers that have been previously mentioned in literature, particularly for patients from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds. Based on simple “yes” or “no” responses, we were able to learn details about our patients’ social history that may otherwise have been overlooked during a standard clinic visit. In particular, the fact that four participants considered themselves homeless raised new and complex issues in their experiences in dealing with a serious illness. A recent systemic review highlighted the importance of providing specialized palliative care and end-of-life care considerations for homeless patients (13), who have increased yet poorly-addressed risk factors for psycho-social-spiritual suffering. In addition to the risk assessment questionnaire, the open-ended questions that we used in our study should be routinely administered by clinicians determine patients’ and families’ main concerns and goals of care.

Interestingly, the tangible barriers that we identified using the needs assessment questionnaire (such as, housing status) were not necessarily perceived as barriers from many of the participants’ perspectives. Participants often mentioned their internal struggles as a source of resistance to palliative care interventions. The lack of financial stability or treatment resources coupled with feelings of hopelessness may be particularly straining for the healing process. As shown in our study, barriers to palliative care emerge in different forms and extend beyond physical and financial needs. For instance, the fear of death as an outcome of their disease may be a barrier if it hinders acceptance of their illness, which in turn may delay access to and acceptance of palliative care and other treatment modalities. Therefore, it is important for healthcare providers to ask open-ended questions similar to the ones used in this study and to listen to the patient’s stories in order to treat them as a whole.

While discussing their experiences with the PPCS team, almost all participants mentioned that “being seen/heard” was one of the most helpful aspects of palliative care in helping them and their families cope with their illness. Our results further support the art of listening as a key component of palliative care and all aspects of healing because this allows patients to become an active participant in their decision-making plan and to take control of their illness. Participants also mentioned other benefits of palliative care that reflected themes from previous qualitative studies such as “personalized symptom management”, “holistic support of patients and caregivers” and “feeling empowered” (6,14). Additionally, effective pain management through medication adjustments offered further relief from physical suffering.

The diversity of the participant population and the unique setting at a large research institution are two important strengths of this study. We were able to interview patients from different socioeconomic, racial, and ethnic backgrounds. While half of our participants had a primary diagnosis of cancer, many had additional chronic and debilitating illnesses such as rare genetic disorders. Importantly, not all patients were receiving end-of-life care. On the other hand, a limitation of this study was that we were unable to recruit an equal number of participants from all three study sites. This was mainly due to a significantly larger number of patients receiving palliative care consultations at the clinical research site compared to the community hospital and outpatient clinic setting.

The stories collected from our participants created a more complete picture of their individual illnesses and healing processes. We hoped to portray our participants based on who they were before their diagnosis and not solely as patients receiving palliative care. Results from this study generated themes that clinicians should focus on during discussions of goals of care with patients and their loved ones. Despite socioeconomic disadvantages and other barriers to palliative care, patients with serious illnesses are still able to experience psycho-social-spiritual healing from knowing that their stories are being heard.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patients and their caregivers for their time, patience, and participation. The authors would also like to acknowledge the staff at Mobile Medical Care, Inc. for their kind support during this study.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at NIH and Johns Hopkins (for Suburban Hospital) (16-CC-0056). Verbal and written informed consents were obtained from all participants.

References

- Richmond C. Dame Cicely Saunders. BMJ 2005;331:238. [Crossref]

- Saunders C. A patient. Nurs Times 1961;57:394-7. [PubMed]

- Sandsdalen T, Rystedt I, Grøndahl VA, et al. Patients’ perceptions of palliative care: adaptation of the Quality from the Patient's Perspective instrument for use in palliative care, and description of patients’ perceptions of care received. BMC Palliat Care 2015;14:54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sandsdalen T, Grøndahl VA, Hov R, et al. Patients’ perceptions of palliative care quality in hospice inpatient care, hospice day care, palliative units in nursing homes, and home care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care 2016;15:79. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arthur J, Yennu S, Zapata KP, et al. Perception of Helpfulness of a Question Prompt Sheet Among Cancer Patients Attending Outpatient Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53:124-30.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hannon B, Swami N, Rodin G, et al. Experiences of patients and caregivers with early palliative care: A qualitative study. Palliat Med 2017;31:72-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berger A, Baker K, Bolle J, et al. Establishing a palliative care program in a research center: evolution of a model. Cancer Invest 2003;21:313-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal SK, Ghosh A, Cheng MJ, et al. Initiating pain and palliative care outpatient services for the suburban underserved in Montgomery County, Maryland: Lessons learned at the NIH Clinical Center and MobileMed. Palliat Support Care 2016;14:381-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lyckholm LJ, Coyne PJ, Kreutzer KO, et al. Barriers to effective palliative care for low-income patients in late stages of cancer: report of a study and strategies for defining and conquering the barriers. Nurs Clin North Am 2010;45:399-409. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Willis G. Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications, 2004.

- National Quality Forum. A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality: A Consensus Report. Available online: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2006/12/A_National_Framework_and_Preferred_Practices_for_Palliative_and_Hospice_Care_Quality.aspx

- Skeath P, Norris S, Katheria V, et al. The nature of life-transforming changes among cancer survivors. Qual Health Res 2013;23:1155-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sumalinog R, Harrington K, Dosani N, et al. Advance care planning, palliative care, and end-of-life care interventions for homeless people: A systematic review. Palliat Med 2017;31:109-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maloney C, Lyons KD, Li Z, et al. Patient perspectives on participation in the ENABLE II randomized controlled trial of a concurrent oncology palliative care intervention: benefits and burdens. Palliat Med 2013;27:375-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]