Healing, spirituality and integrative medicine

“I am not this hair, I am not this skin, I am the soul that lives within.”—Rumi

Spirituality is an important and central theme in healthcare as evidenced by this journal dedicated to the subject. Seminal works have helped to define our concept of spirituality as healthcare providers and are useful as foundations for our understanding of spirituality in the healthcare system (1-5). The 2009 Consensus Conference defined spirituality as: “… the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred” (1). These scholarly works highlight the importance of spirituality in the human experience as it relates to illness and health. The acknowledged relationship between health and spirituality in Western healthcare is further acknowledged through the presence of hospital chaplains in our healthcare institutions who provide a compassionate presence for patients facing great personal challenges (6-8). For the palliative care provider, chaplains play an inextricable role in the interdisciplinary team supporting not only families and patients but the entire palliative care team as well (9). Spiritual care providers such as chaplains provide invaluable service to patients and families and it would be impossible to imagine our Western healthcare system without them and their strong partnership.

Our patients often find comfort and insight from reading and discussing religious teachings, especially in times of adversity, loss and personal confusion. The loss of one’s health or that of a loved one frequently brings people to question the deeper meaning of their lives, the benevolence or retribution of the universe, the choices they have made in life, or the repercussions of past actions. Scripture can provide guidance, and religious leaders can help patients find new understanding when facing life’s challenges and ease the suffering that is common to many (10). The expression: “there are no atheists in foxholes” suggests that even the most skeptical individual may turn towards other sources of support, hope, and comfort when the chips are down or one’s health has taken a turn for the worse. Conversely, non-believers may suffer greater psychological distress than those who identify strongly as believers or have a strong spiritual identity (11). For the palliative care practitioner, being comfortable in addressing the spiritual needs of our patients is often as important as addressing distressing physical symptoms (1,9). Illness creates a loss of identity for many, leading to psychic distress and adding to their suffering (10). This article attempts to address ways in which complementary or integrative medicine can support the human spirit, contribute to healing, and alleviate suffering.

In considering spirituality, integrative medicine and healing, the concept of ‘soul’ inevitably surfaces. It is a term that is often used interchangeably with the ‘human spirit’. Many Westerners subscribe to the presence of a metaphysical aspect to the self—an eternal, absolute ‘self’ referred to as the soul. In contrast, Buddhism, the fourth largest world religion, does not recognize the concept of an eternal soul; whereas, Hinduism (the 3rd largest world ‘religion’) calls the eternal true self Ātman, one’s innermost essence. Nonetheless, a central doctrine of Buddhism acknowledges the cycle of birth, life, suffering, death, and rebirth suggesting that there is a life force within each of us that transcends death and returns in future lifetimes, i.e., reincarnates, a concept familiar to many readers. Most contemporary Christian teaching rejects the idea of reincarnation. However, it is worth noting that early Christians acknowledged reincarnation, although it was rejected as a foundational Christian doctrine in the 4th century by Emperor Constantine, the first Christian Roman emperor. From a mystical Jewish perspective, one kabalistic scholar states that a “single soul can be reincarnated a number of times in different bodies, and in this manner, it can rectify damage done in previous incarnations” (12). While a belief in reincarnation is by no means a prerequisite to the utilization of integrative medicine, many patients and integrative practitioners find the concept helpful in understanding recurring themes in their lives which may be impacting their well-being. In the end, the distinction between soul and spirit is probably more theoretic than practical for healthcare providers. Suffice it to say that many of our patients subscribe to the concept of soul/spirit and it requires the clinician’s utmost respect and acknowledgement.

The inner experience of spirituality transcends most theologies which have been passed down through organized religions as “the (true) word”. While religion generally refers to a codified set of beliefs and practices in a like-minded community, spirituality is a dynamic process entailing an individual’s direct, personal relationship with all that we see (and don’t see) and experience around ourselves, i.e., the Universe/Creation, writ large. In contemporary life, more people characterize themselves as spiritual rather than religious (13-16). The spiritual experience of the Universe/Creation or the divine power is called by various names depending on philosophy, religion, and theological tradition. The Rig Veda states: “Truth is one, and the learned call it by many names”. Physics expresses truth in terms of elementary particles and fundamental forces (gravity, electromagnetism, weak nuclear force and strong nuclear force), Christianity sees God’s love (Divine Love) as the energizing force in creation, whereas mystics and Eastern philosophies understand Creation as ‘energies’ (Qi/Prana) permeating and vivifying everything (animate and inanimate). An individual’s understanding of these fundamental influences and her/his relationship to life are constantly evolving as personal experience, knowledge, wisdom, and awareness grow. Thus, our need for and approach to healing changes as we grow and accumulate greater life experience and, occasionally, more ‘baggage’. When used in this context, a simple but apt definition of healing is the process of getting one’s life in alignment with the needs of one’s soul.

In biology, it is understood that life is a dynamic process offering species the opportunities or evolutionary pressure for growth and maturation as organisms move from birth to death. A reality for palliative care providers is the one universally agreed upon truth: Change is unavoidable. Illness represents change for most people, although for those with chronic illness or disability, the baseline health status may be different than what most of us typically experience. The ancient Essenes believed that life serves as a mirror reflecting to us images and impressions which contain lessons and information for us at various levels depending upon our ability to see what is being revealed (17). Thus, the best of times and the worst of times, health and illness, are potentially valuable opportunities for the human spirit to grow and for the healing of inner wounds and long held, often multi-generational grievances to occur. In Western medicine, we tend to see pathology as the focus of our curative efforts and may not see the opportunities for personal growth that are provided when illness threatens our wellbeing and self-identity. Healing at the level of spirit may occur even when a biological cure for the body is not possible. Thus, a challenge for Western clinicians especially in the field of palliative care is to gently redirect our patient’s attention and help them discover new strengths and personal resilience in their journey through illness. In industrialized, Western medicine, it is the chaplain or palliative care nurse rather than the physician who most often accompanies the patients on her/his journey.

Our role as healthcare providers is to alleviate suffering that does not serve the patient and to facilitate personal growth even in the face of their potential mortality. While our traditional means of supporting patients in Western healthcare depend upon verbal, cognitive, and behavioral methods, many of our patients are too ill or despondent to effectively engage in that process. Pharmacologic approaches to address affective states may address the symptoms, i.e., we treat delirium with drugs; however, drugs rarely get at the root causes of the distress. Integrative modalities typically do not depend upon verbal capacity or level of consciousness or even physical proximity to the patient in the case of intercessory prayer (18), although the weight of evidence for its effect remains contested (19). According to a contemporary Hmong shaman, “supporting the human spirit allows the body to accept Western medicine more effectively” (personal communication with Master Jenee Liusongyaj, Sacramento, CA, 2013). Integrative modalities are thought to support the human spirit in ways that we may not be able to achieve with conventional allopathic approaches. Thus, the inclusion of integrative medicine in clinical practice is potentially beneficial for healthcare maintenance or end of life care, for adult and pediatric patients (20).

Do we heal or cure?

“This moment is given to us to prepare the future and repair the past”.. Tom Forman, early student of Gurdjieff

The goal of Western healthcare is the maintenance of an individual’s optimal wellness or the restoration of health and function when they are absent. Western-trained healthcare providers understand the origins of disease as derangements in biologic functioning, whether inborn or acquired, leading to diminished health, vitality, and longevity. Our Cartesian dualistic view of the world has allowed us to separate the physical processes from the spiritual ones (21).

In contrast to the Western allopathic view, other world cultures view the origins of illness differently. Traditional Chinese Medicine views the healthy state as one in which there is an appropriate flow of subtle energies in the body referred to as Qi (energy) with balance between Yin and Yang, which taken together make the whole. Focusing on the inner being (Yin) can lead to healing, whereas addressing external symptoms (Yang) may achieve curing (22). Some Eastern beliefs invoke (the law of) karma as a major source of life’s experiences including health and illness. Karma may be thought of as the sum total of one’s actions in previous lives and this life, which strongly influence the circumstances experienced in this lifetime and future lifetimes. One can build positive or negative (good or bad) karma through one’s actions and, in so doing, theoretically influence the past and future as well as the present. This concept is not as outlandish as it may seem and hints of this belief are found in the Christian bible. For example, the Apostle Paul alludes to this precept in Galatians and Corinthians: “Every man shall bear his own burden.. for whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap.. Every man shall receive his own reward according to his own labor”. Other non-Western views of the origins of illness include environmental toxins, punishment for sins by a divine power, or fragmentation of the human spirit (so-called “soul loss”) (23). Conceptually, those conditions lead to a loss of wholeness in patients which ultimately manifests as physical or mental disease.

Case vignette: the author admitted a 17-year old Hmong boy with respiratory failure due to Duchenne muscular dystrophy to the pediatric ICU. He was transferred from a community facility where a tracheostomy and gastrostomy tube had been placed. Our goal of care was to get him home with support for his ventilator and feeding tube. In discussing what the medical system could offer his son, the father told the attending physician that the cause of his son’s condition was a curse placed upon the family several generations ago by an evil shaman whom an ancestor had offended. The attending physician told the father that the medical system would address the biological concerns but requested the Hmong community’s healers to be responsible for dealing with the spiritual issues. The Hmong shamans explained that their goal was to make the boy’s spirit whole through a soul-calling ceremony, so that if/when death occurred, he could transition with an intact spirit. The medical goal was optimizing function, whereas the Hmong healer’s goal was spiritual integrity.

This case shows the deep-seated nature of faith and understanding of disruption in the human spirit as a source of illness. As a Western practitioner, the attending physician could have dismissed the father’s explanation and created an adversarial relationship with the family by trying to convince them that his knowledge and understanding were superior to the family’s belief system. Instead, the attending physician made an agreement with the father: the physician would provide all possible care for the body with Western medicine and technology, but the Hmong community’s healers would have to take responsibility for the patient’s spirit. The father found this arrangement acceptable. A traditional Hmong shaman came and visited the boy in the ICU on two occasions performing soul-calling (23) rituals on behalf of his spirit. Anecdotally, the father told the physician that he was the first healthcare provider who had ever mentioned his son’s spiritual well-being, which led to the establishment of long lasting trust.

Integrative medicine practitioners strive to restore wholeness in their patients to facilitate healing of the wounded spirit. Loss of wholeness represents a disruption in one’s inner sense of identity and integrity, i.e., “after my son died, I never felt like myself again”. This state is sometimes referred to as being dis-spirited and may arise with many somatic disorders as well as in PTSD, trauma, and mood disorders (24). While Western-practitioners acknowledge the impact of illness on human emotions (and sometimes vice versa), their primary focus remains the correction of biologic dysfunction (a Yang approach) through pharmacologic, immunologic, or physical means, e.g., surgery or manipulation. Their aim is to optimally restore biological function with the state of the patient’s spirit being a secondary consideration. From a non-allopathic perspective, treating the biologic symptoms may not correct the deeper imbalance which often lies buried within and behind the biologic symptoms. Without treating the underlying imbalance (a Yin approach), the imbalance may manifest again through the same or other biologic processes. While Western practitioners often feel that they are the effectors of the cure and therefore the agents of healing, integrative practitioners more commonly would say that they are simply helping to engage natural healing tendencies residing in each of us, i.e., nature cures and the healer facilitates the process.

Is it alternative, complementary, or integrative?

Confusion about terminology of integrative medicine has existed for two decades. The moniker “alternative” medicine originally suggested that it was an equivalent option (alternative) to conventional Western care and could be chosen in place of the conventional standard therapy (25). That was truer several decades ago when Western approaches to cancer and other devastating conditions could not achieve the successes we see today for many conditions. This situation still pertains in many chronic, incurable medical conditions, chronic fatigue and pain syndromes, and many degenerative conditions for which cure is elusive. As biological approaches to many conditions has increasingly achieved cure and increased survival, the concept of ‘alternative’ therapy has been difficult for Western clinicians to accept due to a lack of rigorous evidence supporting equivalent outcomes. Western medicine has taken a dim view of approaches which purport to be effective but are not supported through rigorous scientific investigation which valued by our healthcare system. The lack of evidence has been a major impediment to the incorporation of integrative modalities into the Western healthcare system (26). Despite significant NIH resources committed to research in the field of complementary medicine, evidence to satisfy critics has not been readily forthcoming. A common explanation given for the absence of hard evidence is that integrative methods may not lend themselves to the scientific method valued by Western medicine. Nonetheless, the widespread use of integrative methods in North America and worldwide, speaks to the value perceived by everyday people striving to improve their health or alleviate their suffering.

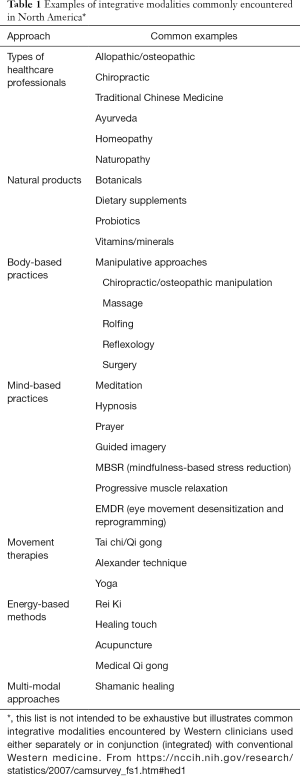

In the late 20th century, Western practitioners discovered that their patients were using other healing approaches in conjunction with conventional Western methods (27,28) and patients frequently failed to disclose their use of complementary modalities to their physicians (29). The more acceptable concept of complementary therapies was adopted although the term ‘alternative’ is retained in the moniker ‘CAM’ (complementary and alternative medicine). In complementary approaches, modalities such as those listed in Table 1 are used in conjunction with Western medicine rather than to the exclusion of Western approaches as was suggested by alternative approaches. The current designation as integrative medicine supports an even broader concept and is used by the NIH and academic medical organizations (28,30,31).

Full table

The nomenclature used by integrative medicine practitioners is often specific to the training they have received and can lead to confusion and misinterpretation when encountered by Western healthcare providers. For example, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) uses common words such as “heat” and “dampness” in various organs referred to as ‘heart’, ‘spleen’ and ‘liver’ which do not specifically correspond to the anatomic structures taught in Western medical schools. (TCM concerns itself with maintaining or re-establishing harmonious balance and proper function which permits the healthy flow of Qi, the vital energy flowing through channels (meridians) interconnecting all organs.) The reasons for this disparity include problems with translation and ways of organizing physiological information. The “Liver” in Chinese medicine, for example, refers to a complex system that mediates many aspects of physiology that includes the systems and mechanisms necessary to hunt or compete (personal communication, David Miller, MD LaC DipOM, Chicago 2017). This system also might better be understood as the “stress system” in Western terms. This terminology has led many Western clinicians to reject TCM and other schools of integrative medicine as gibberish despite their long track record of benefiting patients. This is unfortunate, as the rejection is based merely on ignorance of the meaning of the Chinese medical jargon rather than a more substantial, informed objection. Each system of healthcare is a distinct field with its own language and nomenclature. Many non-western practices are based on thousands of years of clinical trial on countless patients, so their methods and systems of organization should be regarded with an open, curious mind.

Choosing integrative healing modalities

The choice of which modality to use and which practitioner to work with involves many factors, including what sort of practitioners are available in any given community, whether the patient is ambulatory or hospitalized, and whether financial resources exist since many integrative practitioners are not covered by standard health insurance or Medicare. While the cost of an hour’s session with many integrative providers is modest (typically $40–200 per hour session) compared to the cost of a MRI, most integrative modalities require repeated interventions once or twice weekly to be most effective. Public media play some role in hyping supplements or individual practitioners but are typically uncontrolled and no more reliable than any advertisement. Most commonly, people find their way to a practitioner through past experiences with complementary providers, word of mouth, referral by friends, or referral by a healthcare provider. Over the last decade, many multidisciplinary integrative medicine programs have developed affiliated with academic medical centers. Their purpose is to serve as sources of information and contact with integrative practitioners. These programs typically have a wide range of practitioners on staff including physicians, naturopaths, psychologists, massage therapists, herbalists, TCM practitioners, energy healers and others. In general, the practitioners affiliated with such programs have been vetted by local leaders in the field of integrative medicine. While each state has its own laws defining licensure and scope of practice for integrative medicine clinicians, there are useful resources for clinicians and individuals seeking more information, guidance, and resources. This includes the Academic Consortium for Integrative Medicine and Health (30), The American Board of Integrative Medicine (31), and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the NIH (30). For natural medicines, the reader is referred to the Natural Medicine Comprehensive Database (32) and for comparisons of products to Consumer Labs (33).

In deciding whether to seek integrative healthcare, the consumer has several considerations, such as the goals of care, what is available and what is affordable. For example, many patients undergoing therapy for cancer will seek adjunctive support to deal with symptoms, such as nausea and fatigue, associated with chemotherapy, pain associated with cancer, and existential distress brought to light by their medical condition (34). Patients experiencing neurodegenerative disorders may seek Tai Chi (35) instruction to assist with balance concerns, whereas those with cognitive decline may choose mindfulness-based approaches as well as supplements intended to improve memory, in addition to their conventional pharmacologic approaches. Patients with psychiatric conditions may choose energy healing or shamanic approaches as adjuncts to traditional psychiatric care (36). In seeking out integrative methods to deal with their problems, patients are affirming their self-worth and commitment to themselves to heal and get better. When adverse interactions with medically prescribed therapies are absent, it is respectful for Western clinicians to endorse their patients’ efforts to care for themselves. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) techniques are well accepted in Western medicine and even offered in medical school and resident curricula to promote resiliency and wellness in trainees (37). At a minimum, clinicians should know of MBSR resources in their communities or on-line to refer patients (38).

The approaches mentioned above are common in industrialized societies; however, many non-industrialized cultures relate to the world based upon animism, which is neither a faith nor theology. Animism attributes spirit qualities to plants, animals, inanimate objects and natural phenomena in addition to recognizing the spirit in human beings (39). The Hmong mentioned above are such a people and utilize shamans or go-betweens who work between our ordinary reality and what is known as non-ordinary reality, the world of spirit, in which they negotiate and advocate for the sake of patient (23). Native Americans, Australian Aboriginals, ethnic Mongolians, many African tribes and aboriginal South American natives before colonization have an animistic view of the world. In recent decades, shamanism has entered into Western industrialized societies, being introduced by anthropologists who recognized the dynamic and powerful world of “spirit” and the benefit conferred upon humans by mystical dialog between shaman, spirit and humans (24,40). In addition to working with patients from cultures with an animistic world view, shamans in the developed nations do healing work with people from all walks of life and religious backgrounds, including those who adhere to conventional monotheistic religious beliefs.

Case vignette: The author was consulted on a 9-month infant with a fatal, previously unsuspected metabolic condition for goals of care discussion and planning. The infant had markedly depressed sensorium, frequent seizures, spasticity, extremely limited interaction with his environment other than an occasional smile when held by his parents. Within a short time, he required a tracheostomy and ventilator to sustain life. His parents were torn knowing that some of their son was “still there” based upon his intermittent smiles to them. Their love was so strong that they could not bear the thought of removing their son’s life support and suffering the loss of their only child. To help them in their difficult decision of whether to remove life support, the parents consulted with the catholic diocese, the catholic committee on bioethics, several Buddhist thought leaders, and read many papers about bioethics. They felt that the often conflicting information further added to their distress of what was the right thing to do. The author suggested that a shamanic healer who had worked with other families might help them find the clarity they were seeking. With the parents’ permission, the shamanic healer spent several sessions drumming (a drum or rattle is used softly in shamanic healing as a sonic ‘drive’ to shift one’s mental state into a more calm, meditative one) to facilitate their moving out of their heads, and into their hearts to find the answers they sought. After the third session, the parents knew in their hearts what was the best decision for them to make, and they could decide to discontinue their son’s mechanical ventilation at a specific date. On that date, the ventilator was disconnected and the boy placed in his parents’ arms where he was cared for until his death a few days later. Two months later, the mother wrote that she had come to realize that her love for her son and his for her would continue even after the death of the body. It was the realization that she had gained through the shamanic healing process that allowed her to permit discontinuation of artificial life support.

This vignette demonstrates the insight that can be gained through a simple process working non-verbally with a healer or spiritual guide. One can view the transcendent state created in the process of drumming as a deeply prayerful one in which the individual is open to receiving new insights, whether from deep in one’s own memories or from some unseen external source. In the West, some individuals are skilled enough to achieve a transcendent state through meditation, prayer, music, or physical activity (e.g., rhythmic movement, Tai chi). But, for many of our patients, they lack the prior training to achieve such a state. In those cases, a guide such as a native healer may be useful to help people to access those inner realms. In such situations, the shamanic healer featured in the above scenario was of assistance to the family in coming to an understanding of what decisions needed to be made.

Are there risks associated with integrative medicine?

As in all healthcare and life matters, nothing is without risk. Western medicine routinely assesses risk and benefit of therapies and many pharmaceuticals have well accepted side-effect profiles. In a recent study of patients receiving conventional therapy for melanoma, a large number were also using Chinese herbs and other herbal supplements (41). In those using Chinese herbs, the potential for serious interactions between the supplements and primary therapies was estimated to be 86%. Therefore, clinicians must be assiduous in asking specifically about the use of herbal and other supplements when prescribing Western pharmacologic therapies (29,42-44). Well known interactions exist for anticoagulants, immunosuppressant regimens, chelating agents as well as the risk for heavy metal toxicity related to the preparation and storage of certain biological supplements. A classic example is St. John’s Wort commonly used for depression which induces hepatic microsomal enzyme activity, enhancing the elimination of many drugs thereby decreasing their in vivo efficacy. Educating our patients as to why we might advise against certain supplements is the most constructive approach (45). If patients sense they are being judged, they are more likely to withhold the information rather than abandon the supplements. Resources available on the internet such as the British site Safe Alternative Medicine (46) or the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (30) are useful and reliable starting places for reliable information.

Beyond biologicals and supplements, negative effects and complications of most integrative modalities are vanishingly rare especially when one compares them to the known side effects seen with many Western therapies. Acupuncture has been used successfully in patients with thrombocytopenia and immunosuppression without a significant incidence of infections or bleeding complications (47). Rei Ki and other energy healing methods have no known toxicity, if the practitioner is suitably trained. In spite of the rapid thrusts of some chiropractic maneuvers, adverse effects are rare (48). Thus, if a therapy has little or no known toxicity and has potential or known efficacy, it should be considered; whereas, therapies with known toxicity and no credible potential for benefit should be avoided.

Integrative medicine as a tool for healing

Ultimately, healing represents an inner process of transformation which may occur at a level beyond a patient’s everyday awareness. This concept is very different than our allopathic model of curing disease, stamping out cancer, ending muscular dystrophy, etc. The transformational principle contained within inner healing tacitly acknowledges that health and illness each play important roles in our lives, offering opportunities for developing insight, wisdom, and maturity. Whether cure of the bodily symptoms is the priority or simply addressing old issues which have left their residue in our lives the way a deep cut leaves a scar, integrative medicine offers a set of tools and human interactions that often lead to a sense of peace, transcendence and comfort. In contemporary life, being on the receiving end of the medical system is often a frustrating and alienating experience as patients battle with schedulers, insurance companies, and impersonal clinicians who do not have the time to address the source of suffering born by our patients. Supporting the human spirit should be a standard impulse amongst clinicians even if they know they can provide a certain and quick cure for their patient’s ills. It is not that contemporary Western medicine does not acknowledge the deeper unspoken disquietude that many of our patients often bear, but the competing interests of workload, regulations for documentation and informed consent, submitting bills on time, etc. etc. take our attention away from the real service needed by many patients, especially those with advanced disease and those seeking palliative care.

The addition of integrative methods for patients receiving palliative care as adjuncts to symptom management and complementary therapies to augment our supportive care is well established (49-51). Acupuncture has been widely incorporated into Western medical for management of pain, nausea, depression, and existential distress (52). Herbal supplements have been used for reducing anorexia and improving constipation with few side effects (53). Rei Ki has seen increasing use for enhancing relaxation, as an adjunct to pain management, for sleep disturbances and psychospiritual wellbeing (54). Massage has been used successfully in patients with cancer to address pain, anxiety and depression (55,56) although large scale meta-analyses were less compelling (57). Much of the research literature on integrative medicine suffers from limitation in the size and power of studies and lack of adequate controls in some studies. Despite the relative dearth of scientific proof for the efficacy of integrative modalities (aside from acupuncture), the use of these therapies is increasing among all Americans with a shift to mind-body approaches noted in the most recent national statistics (58). Noteworthy is the $30.2 billion spent for complementary therapies documented in the same report (58). The popularity of integrative modalities may be due to their perceived safety, minimal toxicity, and they make patients feel better. While the research evidence does not support a powerful effect of integrative therapies, the public appeal and eagerness to utilize those approaches suggests that the research design is not capturing the benefit perceived by the users.

To provide optimal care to our patients, we should consider developing partnerships with integrative medicine practitioners in our communities for referrals when needed. The best way to know whether a practitioner is reliable is to have an actual session or two with him/her. Above all, we must partner with practitioners who possess absolute personal integrity. Integrity allows an individual practitioner to discern whether their work stems from a place of healing or is simply a manifestation of her/his ego. It is an unfortunate reality that many people who have trained with legitimate teachers and represent themselves as healers are not what they say they are. Asking other colleagues which practitioners they would refer patients to (or go to themselves) for massage, acupuncture, Rei Ki or other adjunctive treatments is also a good place to start building a resource of local providers. If a healer’s sincere intention is to serve the patient’s best interests, then the Peruvian masters tell us the energy to heal will follow. As physicians, we are never able to guarantee that a patient will benefit from working with an integrative practitioner. But, as our experience with individual practitioners grows, we find ourselves saying to our patients, “You know, I’ve had other patients in your situation who have benefited from X, Y, or Z”. It works surprisingly well if the practitioner has integrity and good interpersonal skills.

In closing, I will relate one last case example that demonstrates the seamless role of integrative medicine in a complex family dynamic in the hospital setting.

Case vignette: a 12-year-old girl was referred by her primary physician to the tertiary care hospital for evaluation of acute renal failure. Dialysis was initiated for dramatically elevated creatinine, BUN and phosphate. Within a day of her presentation, she developed tachypnea, diffuse pulmonary infiltrates, and an increasing oxygen requirement necessitating intubation. During intubation, she developed bloody pulmonary edema and hemoptysis. Stabilization of her respiratory status was challenging and a diagnosis of Goodpasture’s disease was made, a rare cause of pulmonary hemorrhage and renal failure in a child her age. Her mother was devastated by her daughter’s illness questioning why God was trying to take away her child. When it became clear that the girl was likely to survive, the mother’s existential distress and spiritual crisis were addressed by suggesting the services of a healer who worked with the mother and her daughter during her prolonged recovery and ultimate renal transplantation. The mother was eager to have the healer work with her daughter but avoided healing work on herself. For the patient, the healing was profound and she had many positive experiences [available as an on-line documentary (59)]. While the mother was deeply grateful for her daughter’s recovery, the medical team felt that she had focused so much on her daughter that she had not worked on her own inner issues, which included feeling that God was punishing her by giving her daughter such a devastating disease.

This vignette demonstrates multiple levels of dis-ease in the family which were at play. The daughter’s illness was an opportunity for the mother to see that life was kind and returned her daughter to her intact with a long life expectancy. And for the daughter, there was the opportunity to help her mother learn that positive lesson through her forbearance during the grave illness. Palliative providers are often faced with similar complex medical situations in which multiple individuals surrounding the patient are impacted by the patient’s illness. Integrative Medicine practitioners much like chaplains can play a supportive role as impartial supporters of the individuals affected by the patient’s condition.

Integrative medicine techniques are potential avenues to discover life’s richness and meaning even when we are confronted with adversity, pain, and suffering. Beyond their potential impact on symptom management, integrative approaches can have profound effects on the inner lives of our patients. For those people who lack a history of devotion or a strong religious community, integrative medicine can provide useful adjuncts to facilitate life closure, resolve old wounds and grievances, and prepare for the transition to whatever is next. In the words of Rabindranath Tagore, “..in all its incalculable immensity, suffering does not block the current of life”. Whether we subscribe to the presence of a soul or not, integrative medicine can augment the care we offer our patients by supporting the human spirit within the frail bodies with which we are entrusted.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank David W. Miller, M.D., FAAP, L.Ac., Dipl. OM, East-West Integrated Medicine, LLC Chicago, IL for his critical reading and helpful comments. The authors wish to thank Master Jenee Liusongyaj (Sacramento, CA) for her encouragement, wise counsel, and compassionate dedication to the children at UC Davis Children’s Hospital. The authors wish to thank Ms Paula Denham, founder of the Sacramento Shamanic Center, and the Collaborative Medicine and Healing Circle of Sacramento for mentorship and inspiration.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the Quality of Spiritual Care as a Dimension of Palliative Care: The Report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885-904. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Isaac KS, Hay JL, Lubetkin EI. Incorporating Spirituality in Primary Care. J Relig Health 2016;55:1065-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Koenig HG. Religion, Spirituality, and Health: The Research and Clinical Implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012;2012:278730. [PubMed]

- Koenig H, King D, Carson V. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Koenig H. Medicine, Religion and Health. Templeton Foundation Press, 2008.

- Harding SR, Flannelly KJ, Galek K, et al. Spiritual care, pastoral care, and chaplains: trends in the health care literature. J Health Care Chaplain 2008;14:99-117. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Proserpio T, Piccinelli C, Clerici CA. Pastoral care in hospitals: a literature review. Tumori 2011;97:666-71. [PubMed]

- Carey LB, Cohen J. The Utility of the WHO ICD-10-AM Pastoral Intervention Codings Within Religious, Pastoral and Spiritual Care Research. J Relig Health 2015;54:1772-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jeuland J, Fitchett G, Schulman-Green D, et al. Chaplains Working in Palliative Care: Who They Are and What They Do. J Palliat Med 2017;20:502-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cassel EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. N Engl J Med 1982;306:639-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weber SR, Pargament KI, Kunik ME, et al. Psychological distress among religious nonbelievers: a systematic review. J Relig Health 2012;51:72-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luzzatto RM. The Way of God: Derech Hashem. Philipp Feldheim, 2009.

- Maschi D, Lipka M. Americans may be getting less religious, but feelings of spirituality are on the rise. Pew Research Center, 2016. Available online: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/01/21/americans-spirituality/, accessed March 1, 2017.

- Oppenheimer M. Examining the Growth of the ‘Spiritual but Not Religious’. NY Times. 2014 July 18, 2014.

- Barrie-Anthony S. 'Spiritual but Not Religious': A Rising, Misunderstood Voting Bloc. (No, they're not just atheists.). The Atlantic 2014. Jan 14, 2014.

- Blumberg A. American Religion Has Never Looked Quite Like It Does Today: Based on these trends, the future of religion in America probably isn’t a church. The Huffington Post 2016. April 15, 2016.

- Braden G. The Divine Matrix: Bridging Time, Space, Miracles, and Belief. Hay House; 2008.

- de Aguiar PR, Tatton-Ramos TP, Alminhana LO. Research on Intercessory Prayer: Theoretical and Methodological Considerations. J Relig Health 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roberts L, Ahmed I, Hall S. Intercessory prayer for the alleviation of ill health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009.CD000368. [PubMed]

- Johnson A, Steinhorn D. Integrative therapies in symptoms management in terminally ill children. In: Goldman A, Hain R, Lieben S. editors. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Care for Children, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Duncan G. Mind-Body Dualism and the Biopsychosocial Model of Pain: What Did Descartes Really Say? J Med Philos 2000;25:485-513. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kemper KJ. Authentic Healing. Two Harbors Press, 2016.

- Fadiman A. The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1997.

- Carson C. Spirited Medicine: Shamanism in Contemporary Healthcare. Otter Bay Books, 2013.

- Ng JY, Boon HS, Thompson AK, et al. Making sense of "alternative", "complementary", "unconventional" and "integrative" medicine: exploring the terms and meanings through a textual analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med 2016;16:134. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agdal R. von BHJ, Johannessen H. Energy healing for cancer: a critical review. Forsch Komplementmed 2011;18:146-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barnes PM, Powell-Griner D, McFann K, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data 2004;27:1-19. [PubMed]

- Clarke T, Black L, Stussman B, et al. Trends in the Use of Complementary Health Approaches Among Adults: United States, 2002-2012. February 10, 2015.

- Jou J, Johnson P. Nondisclosure of Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use to Primary Care Physicians Findings From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:545-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Available online: https://www.abp.org/content/number-diplomates-certified

- American Board of Integrative Medicine. Available online: http://www.abpsus.org/integrative-medicine

- Natural Medicine Comprehensive Database. Available online: www.naturaldatabase.com/

- Comparisons CL-P. Available online: http://www.consumerlab.com

- Pdq Integrative A, Complementary Therapies Editorial B. Topics in Integrative, Alternative, and Complementary Therapies (PDQ(R)): Health Professional Version. PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US), 2002.

- Uhlig T. Tai Chi and yoga as complementary therapies in rheumatologic conditions. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2012;26:387-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alcorn R. Healing Stories: My Journey from Mainstream Psychiatry Toward Spiritual Healing. Medina, OH. Perception Garden Press, 2010.

- Botha E, Gwin T, Purpora C. The effectiveness of mindfulness based programs in reducing stress experienced by nurses in adult hospital settings: a systematic review of quantitative evidence protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2015;13:21-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress, Pain, and Illness. Bantam Dell, 2013.

- Animism. Available online: http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Animism, accessed May 16, 2017.

- Shamanism. Available online: http://albertovilloldophd.com/what-is-a-shaman/, accessed May 16, 2017.

- Loquai C, Dechent D, Garzarolli M, et al. Risk of interactions between complementary and alternative medicine and medication for comorbidities in patients with melanoma. Med Oncol 2016;33:52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh D, Gupta R, Saraf SA. Herbs-are they safe enough? An overview. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2012;52:876-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ben-Arye E, Samuels N, Goldstein LH, et al. Potential risks associated with traditional herbal medicine use in cancer care: A study of Middle Eastern oncology health care professionals. Cancer 2016;122:598-610. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alsanad SM, Howard RL, Williamson EM. An assessment of the impact of herb-drug combinations used by cancer patients. BMC Complement Altern Med 2016;16:393. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grant SJ, Bin YS, Kiat H, et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by people with cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2012;12:299. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Available online: http://www.safealternativemedicine.co.uk, accessed January 8, 2017.

- Ladas EJ, Rooney D, Taromina K, et al. The safety of acupuncture in children and adolescents with cancer therapy-related thrombocytopenia. Support Care Cancer 2010;18:1487-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gouveia LO, Castanho P, Ferreira JJ. Safety of chiropractic interventions: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;34:E405-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weeks L, Balneaves LG, Paterson C, et al. Decision-making about complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients: integrative literature review. Open Med 2014;8:e54-66. [PubMed]

- Conrad AC, Muenstedt K, Micke O, et al. Attitudes of members of the German Society for Palliative Medicine toward complementary and alternative medicine for cancer patients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2014;140:1229-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang KH, Brodie R, Choong MA, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in oncology: a questionnaire survey of patients and health care professionals. BMC Cancer 2011;11:196. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lau CH, Wu X, Chung VC, et al. Acupuncture and Related Therapies for Symptom Management in Palliative Cancer Care: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2901. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chung VC, Wu X, Lu P, et al. Chinese Herbal Medicine for Symptom Management in Cancer Palliative Care: Systematic Review And Meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2793. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burden B, Herron-Marx S, Clifford C. The increasing use of reiki as a complementary therapy in specialist palliative care. Int J Palliat Nurs 2005;11:248-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ernst E. Massage therapy for cancer palliation and supportive care: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:333-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Falkensteiner M, Mantovan F, Muller I, et al. The use of massage therapy for reducing pain, anxiety, and depression in oncological palliative care patients: a narrative review of the literature. ISRN Nurs 2011;2011:929868. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shin ES, Seo KH, Lee SH, et al. Massage with or without aromatherapy for symptom relief in people with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016.CD009873. [PubMed]

- Clarke T, Black L, Stussman B. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2015.

- Quest H. Shamans in the ICU. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dnl_K9_KEkA, accessed January 10, 2017.