Editor’s note:

Prof. Blair Henry (Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center): It is my honor to be named the inaugural chair of the newly created Ethics column for the Annals of Palliative Medicine. My motto has always been: Know better—do better! Palliative care and more specifically end-of-life care are natural nexus for ethical quandaries. In this column I hope to be able to provide our readers with interesting, topical and challenging ethical issues relevant to your clinical setting.

The ethics of suffering in the era of assisted dying

Change both in its substance and pace appears to be increasing dramatically in all sectors of life- and the business of providing health care is not immune to this phenomena. A case in point is our institutional and cultural approach to the end of life. In times prior to the onset of modern medicine (before mid-20th century), death was an ever-present reality in all of life’s stages. In this era, before the creation of the germ theory of disease, no one was immune, and so its presence (death) was at best tolerated and more frequently even accepted. However, as the science of medicine advanced, death was seen as a potentially defeatable enemy, and battle metaphors abounded. However, even though the limits of our mortality could be pushed away—it inevitably needs to be faced, and when it was a series of new tensions revealed themselves: when does dying begin? Just because we can treat—should we? A dance with the devil began: is passive euthanasia tolerable over a more active engagement in futile treatment? Can we allow death to happen if we are not the primary cause of its eventuality? It would be within this milieu that the modern hospice movement alit in North America. Identifying that a dying process existed, responding to it with compassion and good medical care, and then normalizing death as an inevitable part of life formed the bedrock of a new type of medicine. Hospice became the safe haven for those whose death was inevitable, and a place where a measure of quality of one’s life meant more than its quantity (1). And yet the agency of change continues, and slowly over the past 25 years a new movement has taken hold—death as an event at the time and location of the patient’s choice. Over the course of the past 3 decades, religious, ethical, professional and legal barriers have slowly but steadily been moved aside such that now, in Canada, medical assistance in dying has been legalized since the summer of 2016, and currently in the US, six states have legalized physician-assisted suicide (2).

Adaptation to this change in process and the type of response one should have to death and dying has been tenuous and not without its challenges. This paper will attempt to identify some potential reasons why the medical assistance in dying approach and hospice and palliative care movement have been made reluctant and in some cases even hostile bedfellows over the issue of how we ought to respond to suffering.

Suffering: when “all of me is wrong” (3)

Since the dawn of time, human suffering was never seen as a “brain problem”—it was properly considered a human problem (4). At the heart of most of the world’s great religions, the reality of human suffering, its meaning, and its role in one’s life formed the basis of most religious teachings. Take by example the Buddhist tradition: it has been said that founder of Buddhism, Siddhartha Gautama (566 to 480 B.C) encountered during his early years the true hardships of life in the old, the sick, the ascetic and the dying—and that as a result of these encounters, he became convinced that suffering lay at the end of all existence. It is noted that as a central tenet of his enlightenment, Buddha finally understood how to be free from suffering, and ultimately, to achieve salvation. He outlined this in what has been called the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism: suffering exists; suffering arises from attachment to desire; suffering ceases when attachment to desire ceases; and finally that freedom from suffering is possible by practicing The Eightfold Path (5,6).

However, our contemporary understanding and response to human suffering has changed across time and culture, and we do not have a singular framework to help us respond consistently to the suffering of the others. Within the hospice movement, Dame Cicely Saunders formulated a concept of “total pain” in the 1960’s which included physical, psychological, social, emotional and spiritual elements in an attempt to relieve distress, which ultimately changed the biomedical discourse on pain (7). In the early 1990’s, the work of E. Cassell enabled a common language to assist in the articulation of a holistic meaning to our understanding of suffering based on an evolving model of personhood, describing it as a “specific state of severe distress related to the imminent, perceived, or actual threat to the integrity or existential continuity of the person” (8).

Considerable scholarship and research has emerged to engage a deeper understanding of this phenomenon, and efforts have been noted in what can be called a mediational model of suffering. This theory (Figure 1) proposed the following etiology of suffering—a multidimensional and dynamic experience of severe stress that occurs when there is a significant threat to the whole person that sees these threats (stressors) as arising from within or external to the self, the stress is then perceived and mediated by emotions (distress) which motivates us to eliminate the source of stress and we seek ways to cope, and ultimate, if and when the regulatory processes, which would normally result in adaptation, are insufficient—it can lead one to eventually perceive the treat to integrity as unavoidable and then one ultimately succumbs to exhaustion (suffering) (9) (Figure 1).

All of these advancements have borne fruit and have expanded our traditional Western biomedical model approach to pain management that focused too much on the biological aspects of pain and now validate the psychosocial and spiritual components of the experience (10). We slowly moved away from a concept of an “appropriate death” in the early 1970’s, characterized “when internal conflicts, such as fears about loss of control, should be reduced as much as possible; the individual’s personal sense of identity should be sustained; critical relationships should be enhanced or at least maintained, and if possible, conflicts resolved; and the person should be encouraged to set and attempt to reach meaningful, albeit limited, goals such as attending a graduation, a wedding, or the birth of a child, as a way to provide a sense of continuity into the future” (11). To the Institute of Medicine’s heavily conditional definition of a “good death” as being one that is “free from avoidable distress and suffering for patient, family and caregivers, in general accord with patient’s and family’s wishes, and reasonably consistent with clinical, cultural, and ethical standards” (12).

However, the underlying premise of the palliative care model is that the noted progression of events identified in the prescribed etiology stands. Whole person care addresses the stressor (by early intervention) before distress sets, and to bolster coping mechanisms and supports before suffering occurs. When the patient views a “good death” as one that is truly free from distress.

Dualism

When René Descartes uttered his famous treatise “I think, therefore I am”, this 17th century French philosopher left his enduring imprint on the contemporary formulation of what has become known as substance dualism (or Cartesian dualism). He argued that the mind was an independently existing substance—a philosophy that was highly compatible with most theological claims of the day—in that immortal souls occupy an independent “realm” of existence distinct from that of the physical world (13).

It is not the intent of this article to delve into the philosophy of mind, however, the metaphysical concept of dualism, classically known as the mind-body problem is so imbedded in our understanding of suffering it would be remiss not to make some reference to it here. This concept is rooted in the belief that there are two types of realities: physical and non-spiritual entails that our mind has a non-material, spiritual dimension that includes consciousness and possibly an eternal attribute (13). The problem of dualism is most evident when one considers whose role and responsibility it is to address suffering outside of the physical realm. The following section on emerging trends will illustrate this point nicely.

Emerging trends

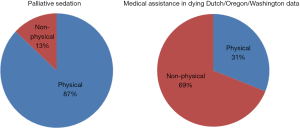

Though no surprise to those involved in end of life care, Figure 2 shows an interesting and emerging picture when one looks critically at the published literature on the types of symptoms purported as primary causes for initiation of either medical assistance in dying or palliative sedation.

For cases involving medical assistance in dying, data reported on statistics for 2015 for physician-assisted deaths in Oregon and Washington states (14,15) and data published in 2005 on the Dutch experience from both euthanasia and physician-assisted deaths (16) showed a split in physical and non-physical symptoms of 31% and 69%.

Data on the use of palliative sedation therapy at the end of life was collated from a 2012 systematic review, which looked at published studies reporting on 621 patients who required sedation at the end of lie in ten retrospective or prospective nonrandomized studies. The split between physical and non-physical was 87% and 13% respectively, almost the inverse of the data from medical assistance in dying (17) (Figure 2).

Since its appearance in the literature in the early 1990’s, the ethical and appropriate use of palliative sedation has been the subject of much debate. Similarly to the observations noted here, current trends in the palliative care community support the use of PST for physical suffering, but its use in non-physical sources of suffering is highly controversial (18,19).

Sudden death—the allure

Perhaps in modern society the problem with dying is not death—it’s the illness, sickness, disability and all the incumbent indignities that seems to go along with it that makes the process of dying unpalatable to our contemporary sensibilities. The elixir to engage in and battle illness lies predominantly in the hope of survival. Once this goal is no longer achievable, for some little to no appetite remains to “live our dying fully”. I might posit that our underlying assumptions about suffering need to be revisited. Wherein we once believed “our desire to explain human suffering, or to make sense of what it means, is a problem, but it is never, ever the problem” has changed—and that perhaps now suffering itself is the problem (9).

Death and dying by generation

The birth of the modern hospice movement is largely attributed to the work of Dame C. Saunders (7). Her population base in that time would have been predominantly from the silent generation or traditionalist generation, representing those born before 1946. Baby boomers represent contemporaneously the growing tide of individuals facing retirement, aging and ultimately death. Traditionalist grew up during the Great Depression and the Second World War and their behaviors were heavily influenced by their experiences. Characteristically, traditionalist would be known as conservative, upholders of traditional family values, church goers and conformist (20). This ethos would have undoubtedly impacted the origins of how hospice care was delivered. Baby boomers, on the other hand, grew up during the Civil Rights Movement and have also been coined the “empty nesters”. They believe rules should be obeyed unless they are contrary to what they want; then they are to be broken; experimental, and individualistic—they are known to want products and services that show their success, and lest we forget they also represent the leaders in both private and governmental circles (21). These characteristics and ethos are undoubtedly responsible, in part, for the current changing legal landscape governing the acceptability of medical assistance in dying.

World Health Organization and palliative care

In its most recent articulation, the World Health Organization defined palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual (22). As laudable as this goal appears, it may have over extended itself into creating an expectation that individuals will not easily achieve. We know that good palliative care services are not available even to those who might desire it. Additionally, the funding to support the full multidisciplinary cadre of services is slowly dwindling. Care from social workers and spiritual care providers remains a mainstay for institutional palliative care units and free standing hospices where limited life expectancy/prognosis is required. However, in the acute and outpatient settings, where earlier interventions in care might be more effective, cutbacks in non-essential clinical staff have left many programs lacking appropriate resources to help in this endeavor.

Conclusions

As we have discussed in this paper, suffering is complex and multifactorial in its manifestation and typically involves negative affective and cognitive states characterized by the initiation of a perceived threat to the integrity of self. Unchecked, this can lead to a sense of perceived helplessness in the face of that threat and subsequently without recourse to the exhaustion of psychological, psychosocial and personal resources (23). As early as 1960, C. Saunders commented that in the provision of good hospice care “mental distress may be perhaps the most intractable pain of all” (24). Perhaps as we go forward down this road, the option for medical assistance in dying can stop being viewed as some sort of failure of hospice care (which it categorically is not), but seen as an important alternate partner in end of life care- in and of itself?

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Editor’s note: Prof. Blair Henry (Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center): It is my honor to be named the inaugural chair of the newly created Ethics column for the Annals of Palliative Medicine. My motto has always been: Know better—do better! Palliative care and more specifically end-of-life care are natural nexus for ethical quandaries. In this column I hope to be able to provide our readers with interesting, topical and challenging ethical issues relevant to your clinical setting.

References

- Tatum PE 3rd, Craig KW, Washington KT, et al. Getting comfortable with death. Evolution of the care of the dying patient. Mo Med 2014;111:298-303. [PubMed]

- Health Law Institute. Dalhousie University. End-of-Life Law & Policy in Canada. Posted 2016. Available online: http://eol.law.dal.ca/?page_id=221

- Saunders C. The symptomatic treatment of incurable malignant disease. Prescribers J 1964;4:68-73.

- Berezin R. The Alternative to Drugs - The real treatment for human suffering. Psychology Today. Posted Oct 23, 2015. Available online: https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-theater-the-brain/201510/the-alternative-drugs

- Essential of Buddhism. Posted Oct. 2004. Available online: http://www.buddhaweb.org/

- Anderson CS. Four Noble Truths. In: Buswell RE Jr. editor. Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Vol. 1. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference USA, 2003:239.

- Clark D. 'Total pain', disciplinary power and the body in the work of Cicely Saunders, 1958-1967. Soc Sci Med 1999;49:727-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cassell EJ. The nature of suffering and the goals of medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Krikorian A, Limonero JT, Mate J. Suffering and distress at the end-of-life. Psychooncology 2012;21:799-808. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wachholtz AB, Fitch CE, Makowski S, et al. A Comprehensive Approach to the Patient at End of Life: Assessment of Multidimensional Suffering. South Med J 2016;109:200-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weisman AD. On Dying and Denying: A Psychiatric Study of Terminality. New York: Behavioral Publications, 1972.

- Field MJ, Cassel CK. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life. Washington DC: National Academy Press, 1997.

- Mastin L. Dualism. The Basics of Philosophy. Posted in 2008. Available online: http://www.philosophybasics.com/branch_dualism.html

- Oregon Public Health Division. Oregon Death with Dignity Act: 2015 Data Summary. Feb 4, 2016. Available online: https://public.health.oregon.gov/ProviderPartnerResources/EvaluationResearch/DeathwithDignityAct/Documents/year18.pdf

- Washington State Department of Health. 2015 Death with Dignity Act Report—Executive Summary. Available online: http://www.doh.wa.gov/portals/1/Documents/Pubs/422-109-DeathWithDignityAct2015.pdf

- Maltoni M, Scarpi E, Rosati M, et al. Palliative sedation in end-of-life care and survival: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1378-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jansen-van der Weide MC, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Wal G. Granted, Undecided, Withdrawn, and Refused Requests for Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1698-704. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anquinet L, Rietjens J, van der Heide A, et al. Physicians' Experiences and Perspectives Regarding the Use of Continuous Sedation Until Death for Cancer Patients in the Context of Psychological and Existential Suffering at the End of Life. Psychooncology. 2014;23:539-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rietjens JA, Voorhees JR, van der Heide A, et al. Approaches to suffering at the end of life: the use of sedation in the USA and Netherlands. J Med Ethics 2014;40:235-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kane S. Common Characteristics of Traditionalists (The Silent Generation). Updated 20 Feb, 2017. Available online: https://www.thebalance.com/workplace-characteristics-silent-generation-2164692

- Pappas C. 8 Important Characteristics Of Baby Boomers eLearning Professionals Should Know. Uploaded 29 Jan, 2016. Available online: https://elearningindustry.com/8-important-characteristics-baby-boomers-elearning-professionals-know

- World Health Organization. National Cancer Control Program: Policies and Managerial Guidelines. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2002.

- Krikorian A, Limonero JT. An integrated view of suffering in palliative care. J Palliat Care 2012;28:41-9. [PubMed]

- Saunders C. Working at St. Joseph’s Hospice, Hackney. Annual Report of St. Vincent’s. Dublin, 1962:37-9.