Assessment of palliative care services in western Kenya

Introduction

Palliative care strives to optimize the quality of life of patients who are living with terminal illnesses. Hospice care focuses on care of patients with a life expectancy of 6 months or less. Palliative and hospice care focus on the physical, psychological, and social stressors that burden patients with life-limiting illnesses and their loved ones (1,2). Patients in hospice experience improved pain and symptoms, feelings of being cared for, and a better quality of life (3). It is estimated that over 20 million people could benefit from palliative care services at the end of life worldwide this year alone. The large majority (78%) of adults that could benefit from palliative care live in low- and middle-income countries (1).

The population who could benefit from palliative care services is rapidly increasing due to the exponentially increasing number of patients with non-communicable diseases (1,4,5). Kenya carries an enormous burden of communicable and non-communicable disease-related deaths—many with suboptimal pain control (6). The majority of Kenyans live in rural communities, which limits their access to palliative pain services. Hospice teams have been developed in some regions of Kenya; however, the majority of these services are in urban centers and not available to the predominant rural community.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends development of palliative care programs, with an emphasis on policy, education, medication availability, and implementation (1). Multiple programs in African countries are successfully providing palliative care services, with improved pain management and quality of life, but there are limitations to their resources, and poverty remains one of the greatest barriers (7). In 2004, only five African countries had palliative care programs. By 2015, over 50% of African countries had palliative care programs; however, these programs only reach approximately 5% of the African population (4).

Despite recent growth in end-of-life services worldwide, doctors and nurses are often insufficiently trained in palliative care (8). Programs designed to better educate healthcare providers in end-of-life care are emerging across several countries (8,9). To address these palliative care needs and better serve African patients, the African Palliative Care Research Network (APCRN) was created in 2010 to create palliative care research applicable to Africa (10). Within the APCRN consortium there are models of home-based care, hospital-based care, and hospice-based care (1,4), as well as pilot programs that integrate palliative care into HIV clinic services (11).

Palliative care is a dynamic process of care, and therapies must be adjusted as the needs of the patient change (4). One of the primary ways that palliative care addresses end-of-life concerns is through pain control, since uncontrolled pain causes depression and interferes with appetite, sleep, and relationships (2). The ability of some pain medications, such as opiates, to provide adequate pain relief is often seen in tension with their addictive and abusive potential. This tension has led to strict regulation and consequently resulted in decreased access to opiates worldwide, particularly in resource-limited settings. For example, low- and middle-income countries account for only 6–10% of the total morphine used worldwide despite comprising 80% of the world’s population (2,9).

Another barrier to opiate use for palliation in resource limited areas is cost. Pre-formulated morphine can be an expensive health care measure in resource-limited areas. However, morphine powder is inexpensive, making it much more affordable for the general population in these countries. In fact, since affordable oral morphine was integrated into the care of hospice patients in 1990, more than 1,600 patients across 11 countries in sub-Saharan Africa have benefited (12).

The primary goal of this study was to assess the current availability and barriers to palliative care as well as healthcare worker knowledge and perceptions on palliative pain control in western Kenya.

Methods

An evidence-based 40-question assessment tool was developed by the study authors, pilot tested through mock interviews with local Kenyan clinicians, and iteratively revised. The assessment tool focused on palliative care and hospice knowledge and awareness, current palliative care and hospice services in western Kenya, palliative pain control practices, and provider perceptions of pain management and the use of opiates. It consisted of multiple-choice and open-ended questions. The assessment was conducted between October 2015 and February 2016 in Siaya County, western Kenya. All level 4 and 5 facilities (e.g., regional and district hospitals) were assessed, as well as a selection of lower-level facilities chosen via convenience sampling, stratified by facility level (e.g., dispensaries, health centers, and health clinics). Enrollment was continued until thematic saturation was achieved.

Key informants were identified based on staff availability at time of survey administration and included clinicians and nurses with direct patient care responsibilities. Written informed consent was obtained prior to interview initiation. Surveys were distributed by a field research team comprised of one of three physician-researchers (P Tulshian, S Villegas, H Zubairi) accompanied by a local Kenyan hospital administrator.

Quantitative data were analyzed with standard descriptive and frequency analyses using Microsoft Excel 2007 (Seattle, Washington, USA). Qualitative thematic analysis was conducted on the open-response data using NVivo 10 software (QSR International, Victoria, Australia). Two physician-researchers independently coded the survey transcripts and a third physician reconciled any differences in their coded themes.

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Partners HealthCare (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA) (No. FWA-3136) and the ethical review committee of Maseno University School of Medicine (Maseno, Kenya) (No. FWA-23701). Prior to initiation of the study, approval and support were received by the Siaya County Health Minister. None of the study authors have any competing interests or disclosures.

Results

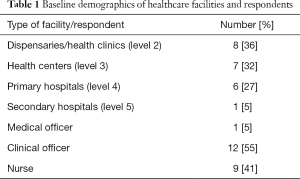

A key informant at each of 22 facilities in Siaya County, western Kenya was surveyed. The facilities included dispensaries/health clinics, health centers, primary hospitals, and secondary hospitals as designated by the Kenya Essential Package for Health. The 22 key informants included 1 medical officer (5%), 12 clinical officers (55%), and 9 nurses (41%) (Table 1).

Full table

Training and education

Twenty (91%) of the 22 providers had received medical training in Kenya. Four (18%) of the 22 providers had received formal training in palliative care, and 5 (23%) of the 22 providers stated patients were referred to their facility for palliative care. Two (9%) of the 22 providers stated they had received formal training in hospice, and 3 (14%) of them had received formal training in end-of-life care. Thirteen (59%) of the 22 providers stated they had cared for a patient at the end of life.

Awareness of palliative care and hospice

The survey asked questions regarding the providers’ awareness of palliative care and what it entails. Every provider surveyed stated they had heard of the term palliative care. When asked about the meaning of palliative care, 5 (23%) of the 22 providers reported that it encompassed all of the following: pain management; active care of the dying; option when nothing else was left; and a way to prevent physical, spiritual, and psychological suffering. The remaining providers (77%) reported various combinations of the above response. When asked who should receive palliative care, 19 (86%) of the 22 providers stated that people with chronic diseases should receive such care.

When asked to explain what hospice was, 10 (46%) of the providers responded it was a place for terminally ill patients, 6 (27%) stated it was a place where palliative care was given, 2 (9%) stated it was a cancer center, and 4 (18%) did not know. Providers were asked about the appropriate time to initiate hospice, of which 6 (27%) stated immediately after diagnosis, 6 (27%) stated it should occur once all medical treatments had been exhausted, 3 (14%) stated it should occur in cases of life-limiting illnesses, 1 (5%) reported it should be initiated in case of a long-term illness with a prognosis of less than 6 months, and 6 (27%) did not know. Eleven (50%) of the providers had referred a patient to hospice and, of these, 9 (82%) referred patients because they were diagnosed with cancer.

Services

Providers were asked about the services provided at their facility. The majority of respondents (19, 86%) stated caregivers and family members take part in caring for a patient dying at the facility, and 3 (14%) respondents stated this did not occur in every case. Providers were asked what they do when there are no curative measures available for patients. Palliative care, supportive care, and hospice were recommended by 13 (59%) providers, 5 (23%) referred, 4 (18%) offered pain management, and 2 (9%) did not respond. Providers reported that end-of-life care should include psychological care (8, 36%), psychological care and pain control (4, 18%), pain control (1, 5%), euthanasia (1, 5%), emergency care (1, 5%), and 6 (27%) respondents did not answer. When asked how suffering should be relieved at the end of life, 10 (46%) answered pain control, 8 (36%) offered pain control and counseling, 2 (9%) recommended palliative care, and 2 (9%) did not respond. Spiritual leaders and spiritual support were available at 9 (41%) of the facilities.

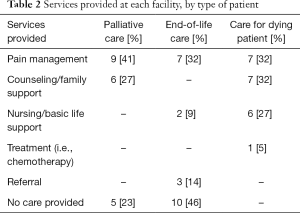

Providers were asked to independently describe the services that would be provided for palliative care, end-of-life care, and for a dying patient. In all scenarios, providers identified pain control as an important component. Providers were more likely to refer patients to other facilities when they were asked specifically about how they cared for patients at the end of life. They were more likely to provide emergency services or medical treatment when asked specifically about the care for a dying patient (Table 2).

Full table

Pain control

When asked what they do when no curative measures remain, 4 (18%) respondents stated pain management as the next step. Five (23%) providers felt pain management should be included in end-of-life care, and 18 (82%) providers felt pain management should be included as a means to relieve suffering. When participants were asked to more specifically define when to use pain medications, 13 (59%) participants stated pain medications should be used to treat severe pain and 2 (9%) participants identified their use for patient suffering.

Nineteen (86%) providers described pain medications as medications used to relieve pain, and most identified them as non-opiate pain medications such as paracetamol (acetaminophen) (55%) and ibuprofen (86%). Six (27%) participants identified opioids as pain medications. Eleven providers (50%) stated that they had previously offered pain medications to patients who subsequently refused. Of those who had refused, the most common reported presumed reason for refusal was that the patient had lost hope (55%).

Eleven (50%) providers identified morphine as a strong pain reliever, 4 (18%) described it as an opioid, and 7 (32%) identified it as an addictive medication. Fourteen (64%) providers knew that morphine was on the WHO essential medication list, 8 (36%) had previously prescribed opioids, and 5 (23%) had prescribed them for palliation. Provider concerns for opioid use included its addictive properties (59%), appropriate dosing (9%), cost (5%), side effects (9%), and availability (5%).

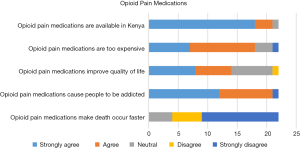

On a 5-point Likert scale, 13 (59%) participants strongly disagreed and 5 (23%) disagreed with the statement that opioids make death occur faster. Twelve (55%) strongly agreed and 9 (41%) agreed opioids caused addiction. Responses varied in terms of the impact of opioids on quality of life and cost (Figure 1).

Discussion

Palliative care is essential to the management of chronic illnesses and end-of-life care. This study sought to evaluate provider knowledge and awareness of palliative care, current palliative services provided, and the role of opioid pain control in palliation in a rural region of western Kenya. All providers interviewed had heard of palliative care, and the majority (86%) stated people with chronic diseases should receive palliative care. However, only a small minority had received formal training in palliative (23%) or hospice (9%) care.

When asked what to do when no other curative measures were available, the majority (59%) of providers recommended palliative care, supportive care, and hospice, and only 4 (18%) providers offered pain control. However, when asked how suffering should be relieved at the end of life, only two providers recommended palliative care, ten recommended pain control only, and eight recommended pain control and counseling. This suggested that providers were able to identify the importance of palliative services in terminal diseases but may not have necessarily understood the importance of relieving suffering through palliation. Furthermore, they viewed pain control as a key component in relieving suffering but not necessarily an essential element of palliative care.

When asked about current practices at their facilities, providers identified pain and symptom control as a key component of palliative services; however, when asked what they did when dying patients were brought to the hospital, several facilities provided basic life support (27%) as well as referrals (23%) to other facilities. Providers repeatedly stated that palliative care services are neglected in rural Kenya and that these services should be made available throughout western Kenya.

Pain control is an important component of end-of-life care. The WHO has identified opioid pain medications such as morphine to be a part of the essential drugs list and emphasizes the importance of utilizing these medications to relieve suffering in patients with non-curable diseases such as cancer and end-stage AIDS (13). Despite these recommendations, the use of pain medication for palliation, and specifically opioids, have remained limited in rural western Kenya. In fact, Kenya carries an enormous burden of HIV/AIDS- and cancer-related deaths with suboptimal pain control. The average morphine-equivalent opioid analgesic consumption per person is 22.1 grams/day compared to an estimated 67 grams/day in resource-rich settings (14).

Opioid pain medications may lead to addiction, and these providers identified this as their greatest concern when using opioid pain medications. Due to this heightened concern for addiction, providers may hesitate to prescribe opiates in situations where the benefits of pain control may outweigh the risks of addiction. Further provider education is needed to emphasize the importance of safely treating patients’ physical suffering at the end of life.

This study showed that, although individuals identified the importance of pain control to relieve suffering (82%), they did not identify this as a standard component of end-of-life care (23%). This suggests a lack of understanding of suffering in end-of-life and palliative care. Furthermore, half of the providers attested to offering pain medications that were refused by patients. The most common reason for this was that providers felt the patient had lost hope. Although, palliative and end-of-life services may not provide hope for curative measures, it is important to focus on other forms of hope. Research in palliative care has identified two forms of hope: “living with hope” and “hoping for something” (15). These are two related and interdependent principles that apply to all individuals and caregivers at the end of life. For instance, the use of pain medications to relieve suffering can provide patients and caregivers with hope and comfort at the end of life.

This study demonstrates the importance of improved education on palliative and hospice care in Kenya. On several instances, when providers were asked about differences in care based on palliative care, end-of-life care, or dying patients, the diversity of responses suggested a lack of understanding about the management of suffering in palliative and end-of-life care. Organizations such as Hospice Africa Uganda that has helped establish palliative care programs in over 50% of African countries show the growing interest in sub-Saharan Africa and the potential for important partnerships among different countries (12).

The limitations of this study included that the overall sampling of facilities was restricted to western Kenya and, thus, may have limited generalizability to other low-resource settings. We attempted to improve the generalizability by conducting surveys among multiple levels of health care facilities in the region. Additionally, there was a potential for social desirability bias; however, we tried to mitigate this by creating multiple questions on similar topics and by using interviewees who were directly involved with patient care and not directly involved with the study.

Conclusions

Palliative care and hospice services were identified by providers as important components in the management of chronic illnesses and end-of-life care in western Kenya. Although all interviewed providers had heard of palliative care, the majority lacked any formal training. Current palliative care services, including psychological support and pain control, are significantly limited. Further provider education on palliative and hospice services as well as increased access to pain medications including opioids are necessary to improve the care of patients in western Kenya.

Acknowledgements

Any clerical costs were covered by the Division of Global Health and Human Rights, Department of Emergency Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This study was approved by the institutional review board of Partners HealthCare (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA) (No. FWA-3136) and the ethical review committee of Maseno University School of Medicine (Maseno, Kenya) (No. FWA-23701) and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

References

- World Health Organization. Global atlas of palliative care at the end of life. 2014. Available online: http://www.who.int/nmh/Global_Atlas_of_Palliative_Care.pdf

- Lohman D, Amon JJ. Evaluating a Human Rights-Based Advocacy Approach to Expanding Access to Pain Medicines and Palliative Care: Global Advocacy and Case Studies from India, Kenya, and Ukraine. Health Hum Rights 2015;17:149-65. [PubMed]

- Too W, Watson M, Harding R, et al. Living with AIDS in Uganda: a qualitative study of patients' and families' experiences following referral to hospice. BMC Palliat Care 2015;14:67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Downing J, Grant L, Leng M, et al. Understanding Models of Palliative Care Delivery in Sub-Saharan Africa: Learning From Programs in Kenya and Malawi. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:362-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Powell RA, Ali Z, Luyirika E, et al. Out of the shadows: non-communicable diseases and palliative care in Africa. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Downing J, Gomes B, Gikaara N, et al. Public preferences and priorities for end-of-life care in Kenya: a population-based street survey. BMC Palliat Care 2014;13:4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grant L, Brown J, Leng M, et al. Palliative care making a difference in rural Uganda, Kenya and Malawi: three rapid evaluation field studies. BMC Palliat Care 2011;10:8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malloy P, Paice JA, Ferrell BR, et al. Advancing palliative care in Kenya. Cancer Nurs 2011;34:E10-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hannon B, Zimmermann C, Knaul FM, et al. Provision of Palliative Care in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Overcoming Obstacles for Effective Treatment Delivery. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:62-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Powell RA, Harding R, Namisango E, et al. Palliative care research in Africa: consensus building for a prioritized agenda. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014;47:315-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lowther K, Selman L, Simms V, et al. Nurse-led palliative care for HIV-positive patients taking antiretroviral therapy in Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet HIV 2015;2:e328-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Merriman A, Harding R. Pain control in the African context: the Ugandan introduction of affordable morphine to relieve suffering at the end of life. Philos Ethics Humanit Med 2010;5:10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. National cancer control programmes. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/nccp/en/

- O'Brien M, Mwangi-Powell F, Adewole IF, et al. Improving access to analgesic drugs for patients with cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:e176-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kylmä J, Duggleby W, Cooper D, et al. Hope in palliative care: an integrative review. Palliat Support Care 2009;7:365-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]