Psychiatry and interdisciplinary pediatric palliative care: a scoping review

Highlight box

Key findings

• Sixty-five references met criteria regarding palliative management of psychological distress in adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with serious illness.

• Eight themes included AYA vulnerability, barriers/facilitators to appropriate treatment, education/training of pediatric palliative care (PPC) team, patient/provider perspectives, and interventions.

What is known and what is new?

• AYAs present unique challenges, as normative development disrupted by terminal illness requires an interdisciplinary approach to care. National Consensus Project and international PPC standards include systematic management of psychological/psychiatric aspects of palliative care.

• Barriers exist in palliative management of psychological distress including lack of mental health training, routine screening, and collaboration among subspecialty teams.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Need for quantitative research guiding PPC practice, collaboration, and instructional design for PPC interdisciplinary team continuing education in the psychiatric management of vulnerable populations such as AYAs with serious illness.

Introduction

Background

Psychological distress is common in patients suffering from serious illness (1,2), and adolescents and young adults (AYAs) diagnosed with a serious illness are potentially the most vulnerable. Developmental risk factors associated with mental health comorbidity in AYAs are present in every aspect of their lives: socially, educationally, sexually, emotionally, relationally, spiritually, and culturally (3-9). Pediatric palliative care (PPC) teams are often consulted in these instances given their interdisciplinary approach to holistic management of complex patient scenarios. According to guidelines from the National Consensus Project (NCP) for Quality Palliative Care, and international standards for PPC, a systematic approach to the psychological and psychiatric aspects of care is expected by all palliative care (PC) programs, yet even regular screening of such distress continues to fall short, much less its holistic management and documentation (10-13). One reason for this shortcoming may be the wide variability in PC interdisciplinary teams (IDTs) across the nation. Most U.S. programs are not meeting recommended staffing standards of a core PPC team [physician (MD), advanced practice registered nurse (APRN), registered nurse (RN), social worker (SW), and chaplain], and even more unlikely is the integration of psychology or psychiatry (22% and 4% of responding teams, respectively) (14). Additionally, psychological responsibilities across the PPC IDT remain nebulous, and overlap in many cases (2,15-28). Studies have shown that many members of IDTs are uncertain regarding their colleagues’ baseline training (21,22,25), and therefore struggle to understand clinical boundaries within the IDT. Efforts have been made to specify standard competencies which could inform respective primary collegiate curricula, but few still encompass AYA-specific palliative skills (23,24,27,29-32). Overlap of roles can be problematic, for instance among chaplains, child life specialists and RNs who all have expertise in the recognition of symptoms in their distinct avenues of influence including spiritual/existential, developmental, and relational distress (19,21,33). Psychologists and SWs: both trained to understand how serious illness can affect an entire family unit; assess anticipatory grief and implement interventions such as identifying community resources; and are skilled in research and advocacy (17). Prescribing providers such as MDs, APRNs, and psychiatrists share the ability to assess for mental health disturbances such as anxiety and depression, and can prescribe subsequent medical treatment (28,34). This does not mean they all receive the same level of intensity in psychological training. Clearly a psychiatrist’s collegiate curriculum more intently focuses on psychological issues throughout their entire program, whereas MDs and APRNs might have a course or two devoted to such studies. This may result in heavy reliance on the psychosocial expertise of SWs embedded in PPC teams when needs arise; however, SWs are not trained to prescribe. This is where collaboration becomes vital. However, it has been said that PPC is still a young discipline and, while larger academic pediatric centers have access to consultative-liaison services in psychiatry and psychology, collaboration models among specialty PC and subspecialties within the field remain in their infancy (35). Therefore, even the most resourced teams have difficulty delineating clinical margins within the vulnerable population of seriously ill AYAs experiencing comorbid psychological distress.

Rationale and knowledge gap

Differentiating between psychosocial, psychological, and psychiatric aspects of PC (2) is an important first step to understanding the knowledge gap (see Table 1). The term “psychological” will encompass psychological and psychiatric services, and psychiatric distress where appropriate for the duration of this article.

Table 1

| Term | Definition | Palliative care |

|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial | Relating to the interrelation of social factors and individual thought and behavior | Typically delegated to LSWs |

| Psychological | Relating to the mental and emotional state of a person | Expected to be recognized by RNs, APRNs, MDs, then followed up by supportive services such as counselors, psychologists |

| Psychiatric | Relating to mental illness or its treatment | Models of collaborative care for mental illness are based on the availability of each region’s resources (i.e., in large academic centers with ample resources, psychiatry is a subspecialty that palliative patients are referred to if mental illness becomes a concern) |

LSWs, licensed social workers; RNs, registered nurses; APRNs, advanced practice registered nurses; MDs, physicians.

Integration of psychologists and psychiatrists in PPC remains widely uncommon in the US. Therefore, PPC teams typically function without the involvement of psychological providers, are expected to manage psychological distress, yet continue to lack formal mental health professional training and continuing education opportunities (15,36,37). Understanding the aspects of the need as well as the overlap in delineation of roles and responsibilities among team members may inform more systematic management of psychological distress in AYAs with serious illness.

Objectives

This paper aims to answer two questions: (I) What is the state of the evidence regarding the intersection of PPC and the management of psychological distress in AYAs with serious illness? (II) What is the state of current psychological learning opportunities for palliative providers across multiple disciplines? Given its multiple facets of inquiry, a scoping review was deemed the most appropriate method to systematically map the most current literature. Relevant key elements which conceptualize the review questions will be determined, such as discipline, geography, population, methodology, themes, and gaps in knowledge. This article is presented in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR reporting checklist (38) (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-501/rc).

Methods

Preparation phase

Dividing between systematic versus scoping review was accomplished by following a flow diagram from the University of Maryland, Baltimore’s Health Sciences and Human Services Library (HSHSL) which can be found at https://guides.hshsl.umaryland.edu/systematic/. Given the needs for more than one research question, and to perform a basic qualitative content analysis for mapping, a scoping review format was deemed most appropriate. Discussion with an HSHSL librarian occurred via Zoom on May 31, 2023, where research questions were refined, relevant databases were chosen, and combinations of terms using respective Boolean and proximity search operators were chosen. The most recent search was executed on June 17, 2023. Immersion in the data quickly identified an existing population-concept-context framework (39), regarding the intersection of psychology and PPC, which informed the development of an associated scoping review protocol. The protocol was registered with the Center for Open Science on June 19, 2023, using the Open Science Framework (OSF) for optimal transparency and reproducibility of the review (osf.io/fb48n). Between June and July 2023, one reviewer searched five databases, GoogleScholar, and seven texts, as well as interviewed several content experts in PPC to ensure inclusion of all relevant records. Databases included Scopus, PubMed, Embase, PsycInfo, and Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). Content experts who were interviewed were specifically chosen in order to represent the interdisciplinary PPC team including MDs, fellowship directors, nurse practitioners, SWs, pharmacists, chaplains, and consultative psychiatrists. Full electronic search strategies for each database are included in the registered OSF protocol, however an example from Embase is included here:

- Used the basic search field, and unchecked the equivalent subjects option;

- Used Emtree terms, truncation for psych* and educat*, and proximity operators /exp and :ab,ti;

- ‘palliative’ AND mental:ab,ti AND disease:ab,ti AND [english]/lim AND ([adolescent]/lim OR [young adult]/lim) AND [2018-2023]/py;

- (‘palliative’ OR ‘palliative therapy’/exp OR ‘palliative therapy’ OR ‘palliative nursing’/exp OR ‘palliative nursing’ OR ‘collaborative care team’/exp OR ‘collaborative care team’ OR ‘collaborative learning’/exp OR ‘collaborative learning’ OR ‘multidisciplinary team’/exp OR ‘multidisciplinary team’ OR ‘interdisciplinary education’/exp OR ‘interdisciplinary education’ OR ’social work’/exp OR ‘social work’ OR ‘hospital subdivisions and components’/exp OR ‘hospital subdivisions and components’ OR ‘pharmacist’/exp OR ‘pharmacist’) AND (‘mental disease’:ab,ti OR ‘psychiatric treatment’:ab,ti) AND [english]/lim AND ([school]/lim OR [adolescent]/lim OR [young adult]/lim OR [middle aged]/lim) AND [2018-2023]/py.

Limiters for each database included date, age, and language: 2018–2023, AYAs ranging from 10–45 years of age, written in English. The North American age range for AYAs is defined as 15–39 years (3). However, not all databases offered a search limiter entitled “adolescents and/or young adults”. Rather, each database gave varying age ranges. Therefore, ages 10–45 were chosen to encompass all age range limiters offered among the collective databases, which include the desired 15–39 range.

Final sources described interdisciplinary PC and management of psychological/psychiatric distress in seriously ill AYAs, were written in English, and were completed in the U.S. between 2018–2023. International citations were included if American literature was reviewed, or if authors described internationally developed PC standards by which American providers must practice.

Organization phase

The processes of extraction, analysis, and synthesis were completed using the Joanna Briggs Institute scoping review methodological approach (39) and were guided by the PRISMA checklist with Scoping Review extension. Title, abstract, and full text eligibility screening were completed systematically, by one reviewer, using the online Covidence screening tool. The same reviewer independently utilized Covidence software for data organization, using a deductive approach according to the set framework and codes (see Table 2) within the predetermined OSF protocol.

Table 2

| General information | Key characteristics | Population studied | Context | Outcomes | Mapping checkboxes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author | Paradigm/method | Palliative team | Topic/focus/question | Findings | AYA vulnerability |

| Date published | Type of evidence source | Patient | Location of study/whether pediatric or adult facility | Future research | Palliative care role |

| Title | Family | Sample size | Limitations | Professional competencies | |

| Location of author | Discipline within palliative team | Other demographics | Standards/guidelines | ||

| Age of patient(s) | Provider perspective | ||||

| Gender | Education/training | ||||

| Serious illness | Interventions | ||||

| Barriers/facilitators |

AYA, adolescent and young adult.

Mapping for barriers/facilitators was further subcategorized into nine options which included the following: (barriers) (I) attitudes/perceptions of mental health/AYAs, (II) lack of resources/access to psychological/psychiatric services, (III) lack of provider education/professional training, (IV) lack of provider management skills, and (facilitators) (V) psychological education in undergraduate/medical school, (VI) professional training/continuing education, (VII) interdisciplinary training for PC teams, (VIII) collaboration models, and (IX) integrated teams.

Data were exported as a .csv file from Covidence into Microsoft Excel and compiled into a table available at https://cdn.amegroups.cn/static/public/apm-23-501-1.pdf. However, given the large amount of information extracted, creative approaches were taken to convey results. Data within excel were recoded into numerical values for sums, imported into a user-friendly business intelligence software called Tableau, and analyzed in charts and graphs according to research questions. Results will be presented in figures according to the relevant key elements which conceptualize the review questions, as previously listed.

Results

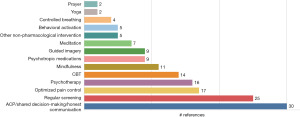

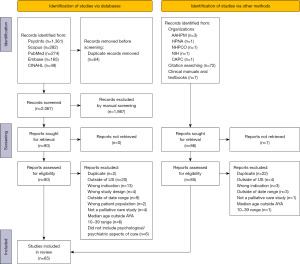

A total of 2,217 citations were identified from electronic databases, reference trails, and clinical manuals. After duplicates were removed, 2,153 references were screened per title and abstract, and 1,987 sources were excluded. One book chapter was unable to be retrieved, leaving 165 full texts to be screened for eligibility, of which 65 met final inclusion criteria (see PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1 and table available at https://cdn.amegroups.cn/static/public/apm-23-501-1.pdf). Seven sources found in reference trails were outside of the date range yet were included given their current relevance to the field.

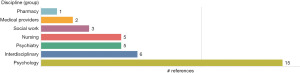

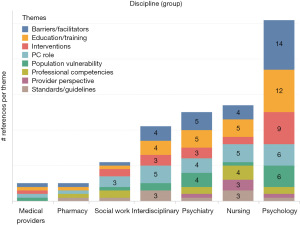

Who’s writing?

Of the authors that specified their discipline (n=37), 40% of the included references were written by authors from the field of psychology, followed by the IDT, psychiatry, nursing, social work, medical providers, and pharmacy (see Figure 2).

Most literature was written in the eastern region of the United States, more specifically authors from Boston Children’s Hospital and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Massachusetts (see Figure 3).

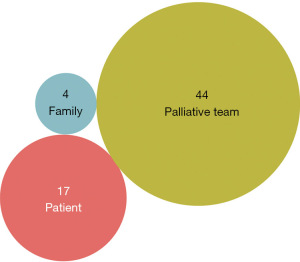

Who’s being studied?

Sixty-eight percent reported on the PC team population, while the rest focused on the patient and family (26% and 6%, respectively) (see Figure 4).

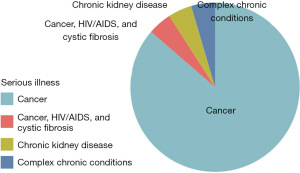

A total of 22 references described cases of AYAs with specified serious illness, and only two studied non-cancer diagnoses (see Figure 5).

Of those same 22 studies, very few specified genders (n=5), and four were based on female cancers. The male study was a qualitative case study based on one male oncology patient.

How’s it being written?

The following tree map displays data in nested rectangles, using dimensions to define the hierarchy, quantity, and patterns among extracted data according to methods of study (39) (see Figure 6). Thirty-five percent, the majority of included literature, used qualitative methods (23 total references). However, professional practice competencies and guidelines only represented 6% of the literature, and symposia presentations were even fewer at only 4% (total of four references and three references, respectively).

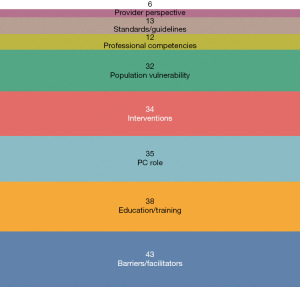

What’s being written?

Eight total themes were noted throughout the included literature, many overlapping in each reference. For example, a single study discussed educational background and competencies of a discipline, then concluded with lack of training as a barrier in PC; therefore, the single reference was coded as covering multiple themes (see Figure 7). All disciplines, and over half of all included references, concluded with presenting the need for more education in the realm of managing comorbid distress in AYAs with serious illness (see Figure 8).

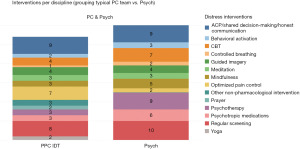

Interventions most repeated in the literature were early discussion of goals and advance care planning (ACP). This included fostering shared decision-making and honest communication between provider, patient, and family; regular assessment of psychological distress in AYAs; and optimized pain control as an eliminating factor contributing to psychological distress (see Figure 9).

Both psychology and the PPC IDT wrote about regular screening and ACP. While optimized pain control was more often addressed by the PPC IDT, counseling or talk-therapy (referred to as psychotherapy), cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and other psychological interventions were more commonly discussed by the psychology and psychiatry groups (see Figure 10).

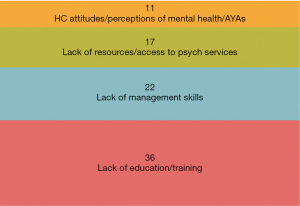

Multiple barriers to managing psychological distress in AYAs with serious illness were mentioned in the included articles. Lack of professional education and mid-career training in both psychiatric and PC disciplines posed the largest barrier to the management of distress, followed by lack of appropriate management skills by PC providers; lack of resources or patient access to psychology/psychiatry services; and finally poor perceptions and attitudes surrounding mental health in AYAs (see Figure 11).

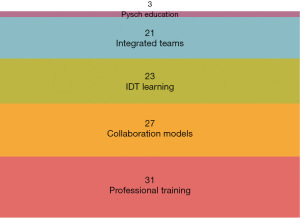

Facilitators to the provision of adequate psychological support to seriously ill AYAs were subcategorized to include more professional training, collaboration among psychology/psychiatry and PPC teams, increased availability of IDT learning opportunities, the integration of psychology/psychiatry services into PPC teams, and psychiatric education (both PC education in psychology programs and psychological education in PC programs). Fairly even frequency distributions were noted in facilitators among existing models for professional and interdisciplinary training, as well as collaboration and integration between psychology/psychiatry and PPC teams (see Figure 12).

Discussion

Key findings and implications

In this scoping review, 58 primary references were identified which addressed the roles, responsibilities, and training of PPC providers in the management of psychological distress in AYAs with serious illness. Given the wide range of disciplines covered in this review, and the need to include seven additional resources which were out of the specified date range, it is clear there remains a gap in specific guidance regarding this vulnerable population. Findings largely focus on the PC team and barriers vwhich prevent holistic management of distress in AYAs with cancer diagnoses. Tailoring palliative interventions according to developmental and cultural influences for the AYA population requires a significant amount of time and understanding. Current literature highlights the importance of AYAs being treated in pediatric institutions, where care plans are created surrounding normative developmental needs of AYAs; however professional educational opportunities specific to the vulnerable AYA with serious illness continues to be insufficient in adult and pediatric institutions alike. Clinical competence suffers due to the absence of training, limited access to subspecialty consultative services, lack of delineation among overlapping roles, and lack of standardized collaborative models. Feasible PC-specific interventions which help to eliminate risk factors for distress were found, and mainly included early and honest communication and ACP, routine distress screening, and optimized pain control. These findings could be especially helpful for the palliative MD, advanced practice provider, nurse, and SW. Finally, two recommendations for systemic issues related to clarifying the intersection of psychiatry and PPC were consistently highlighted in the literature: PPC/psychology/psychiatry collaborative models and continuing interdisciplinary education for PPC providers; both of which will promote the systematic management of psychological distress in AYAs with serious illness, therefore fulfilling the national and international expectations for quality PPC. The breadth of information this scoping review brings will promote further PPC research in vulnerable populations, as well as educational initiatives specific to AYAs experiencing psychological distress.

Limitations

Only three citations (8,9,40) reported on racial disparities that exist in addition to the already-vulnerable AYA. Additionally, non-cancer complex chronic illnesses were not well represented in the literature (n=2). Furthermore, oncology standards recommend integrated psychological support within oncology teams, and subsequently have their own psychology services. The included literature rarely addressed this aspect of care, and how PPC IDTs fit within that model. Finally, while the need for rigor in all aspects of human science research is understood, and multiple reviewers decreases the risk for bias, this publication served as a portion of a larger dissertation completed through the University of Maryland, Baltimore. As a result, this scoping review was completed and written according to the requirements of the university necessitating sole authorship.

Actions needed

To realize NCP guidelines’ third domain and satisfy the international PPC guidelines’ expectations for psychological aspects of care, there is a universal need for knowledge-sharing between psychology and PPC. A globally accessible systematic approach to interdisciplinary skill training, geared toward mid-career adult learners, will optimize care for seriously ill AYAs experiencing comorbid psychological symptoms.

Conclusions

AYAs with serious illness are a unique population due to their rapidly transitioning stages of normative development during a life-limiting illness. While a scoping review is not meant to inform practice or policy, this review has identified several gaps which should guide future research with respect to the research questions at hand.

What is the state of the evidence regarding the intersection of PPC and the management of psychological distress in AYAs with serious illness?

Psychologists from large academic pediatric centers are responsible for most included literature, which is methodologically qualitative. References from 2018–2023 focus largely on the need for role delineation and collaboration among the interdisciplinary PPC team and consultative psychiatry, mainly among the AYA cancer population. While standardized practice will be difficult to attain due to the variable makeup of PPC IDTs and availability of mental health resources across the nation, PPC providers can begin by routinely assessing for psychological distress and being open to early ACP with AYAs facing serious diagnoses. Quantitative studies covering the feasibility and efficacy of collaborative models among psychology/psychiatry and PPC IDT could inform best practices in well-resourced areas, which could lead to the advocacy of policy change requiring integration of psychological expertise into PPC teams who serve in less-resourced regions. More information is needed in PPC practices among racially diverse areas of the country, and studies should focus on the patient and family. Additionally, reviews are needed regarding the validity and reliability of distress screening in AYAs with serious illness in subpopulations that are most at risk.

What is the state of current psychological learning opportunities for palliative providers across multiple disciplines?

Primary education curricula which include psychological training heavily depend on the discipline track chosen in undergraduate and graduate programs. While baseline education varies widely, all professionals within the PPC team are expected to be aware of psychological distress to some extent and possess the ability to communicate and document concerns. Efforts have been made to provide courses specific to PC in medical, nursing, pharmacy, psychology/psychiatry, and social work programs, and some competency guidelines even require such training. However, to the best of our knowledge and searching through this scoping review, none are specific to AYAs. Efforts have also been made to provide one to two-week psychiatric rotations in clinical PPC fellowships, but most remain elective. National organizations such as the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine continue to include presentations at annual assemblies, and plan to offer a one-day clinical course on essential psychiatric skills for palliative providers in November 2023.

Interdisciplinary continuing education and online learning opportunities tailored to mid-career pediatric palliative professionals will help delineate roles among overlapping disciplines in the management of comorbid psychological distress in AYAs with a life-limiting illness. This can inform best practices in the treatment of AYAs. This review advocates for knowledge-sharing among disciplines as an evolving educational approach to understanding roles and responsibilities among vulnerable AYA populations in PPC.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my thanks to Drs. McPherson and Wright of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, for editing early drafts of this work.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The author has completed the PRISMA-ScR reporting checklist. Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-501/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-501/prf

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-501/coif). The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Jacobowski N. Pediatric palliative care and end-of-life in childhood cancer: Opportunities for child and adolescent psychiatrists. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2016;55:S59-60. [Crossref]

- O'Malley K, Blakley L, Ramos K, et al. Mental healthcare and palliative care: barriers. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2021;11:138-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdelaal M, Avery J, Chow R, et al. Palliative care for adolescents and young adults with advanced illness: A scoping review. Palliat Med 2023;37:88-107. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Albrecht TA, Keim-Malpass J, Boyiadzis M, et al. Psychosocial Experiences of Young Adults Diagnosed With Acute Leukemia During Hospitalization for Induction Chemotherapy Treatment. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2019;21:167-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pao M, Mahoney MR. "Will You Remember Me?": Talking with Adolescents About Death and Dying. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2018;27:511-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Husson O, Huijgens PC, van der Graaf WTA. Psychosocial challenges and health-related quality of life of adolescents and young adults with hematologic malignancies. Blood 2018;132:385-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peck KR, Harman JL, Anghelescu DL. Provision of Adequate Pain Management to a Young Adult Oncology Patient Presenting with Aberrant Opioid-Associated Behavior: A Case Study. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol 2019;8:221-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kentor RA, Krinock P, Placencia J, et al. Interdisciplinary symptom management in pediatric palliative care: A case report. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol 2021;9:242-50. [Crossref]

- Sample E, Mikulic C, Christian-Brandt A. Unheard voices: Underrepresented families perspectives of pediatric palliative care. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol 2021;9:318-22. [Crossref]

- Ferrell BR, Twaddle ML, Melnick A, et al. National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care Guidelines, 4th Edition. J Palliat Med 2018;21:1684-9.

- Benini F, Papadatou D, Bernadá M, et al. International Standards for Pediatric Palliative Care: From IMPaCCT to GO-PPaCS. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022;63:e529-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cress AE. Palliative Measurement of Anxiety in Young Women With Gynecologic Malignancy: A Review of Three Instruments. Illness, Crisis & Loss 2023;31:704-19. [Crossref]

- Stoyell JF, Jordan M, Derouin A, et al. Evaluation of a Quality Improvement Intervention to Improve Pediatric Palliative Care Consultation Processes. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2021;38:1457-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rogers MM, Friebert S, Williams CSP, et al. Pediatric Palliative Care Programs in US Hospitals. Pediatrics 2021;148:e2020021634. [PubMed]

- Buxton D. Child and adolescent psychiatry and palliative care. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;54:791-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rodin G, An E, Shnall J, et al. Psychological Interventions for Patients With Advanced Disease: Implications for Oncology and Palliative Care. J Clin Oncol 2020;38:885-904. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farabelli JP, Kimberly SM, Altilio T, et al. Top Ten Tips Palliative Care Clinicians Should Know About Psychosocial and Family Support. J Palliat Med 2020;23:280-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jacobowski N. Pediatric palliative care and child and adolescent psychiatry. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2016;55:S303. [Crossref]

- Basak RB, Momaya R, Guo J, et al. Role of Child Life Specialists in Pediatric Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;58:735-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berger AM, Hinds PS, Puchalski CM. Handbook of supportive oncology and palliative care: Whole-person adult and pediatric care New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2019.

- Ronald AH, Hooper LM, Head BA, et al. Insights and experiences of chaplain interns and social work interns on palliative care teams. Death Stud 2020;44:141-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Mahony S, Baron A, Ansari A, et al. Expanding the Interdisciplinary Palliative Medicine Workforce: A Longitudinal Education and Mentoring Program for Practicing Clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020;60:602-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Orloff SF. Pediatric hospice and palliative care: The invaluable role of social work. In: The Oxford textbook of palliative social work, 2nd ed New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2022:394-403.

- Schneider NM, Steinberg DM, Pahl DA, et al. Ethical quandaries at end of life: Navigating real-world case examples as a pediatric psychologist. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol 2023;11:244-51. [Crossref]

- Hildenbrand AK, Amaro CM, Gramszlo C, et al. Psychologists in pediatric palliative care: Clinical care models within the United States. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol 2021;9:229-41. [Crossref]

- Edlynn E, Kaur H. The Role of Psychology in Pediatric Palliative Care. J Palliat Med 2016;19:760-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muriel AC, Wolfe J, Block SD. Pediatric Palliative Care and Child Psychiatry: A Model for Enhancing Practice and Collaboration. J Palliat Med 2016;19:1032-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wolfe J, Hinds PS, Sourkes BM. Interdisciplinary pediatric palliative care. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2022.

- Pruskowski J, Patel R, Brazeau G. The Need for Palliative Care in Pharmacy Education. Am J Pharm Educ 2019;83:7410. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jonas D, Patneaude A, Purol N, et al. Defining Core Competencies and a Call to Action: Dissecting and Embracing the Crucial and Multifaceted Social Work Role in Pediatric Palliative Care. J Pain Symptom Manage 2022;63:e739-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thompson AL, Schaefer MR, McCarthy SR, et al. Competencies for Psychology Practice in Pediatric Palliative Care. J Pediatr Psychol 2023;48:614-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lippe M, Davis A, Stock N, et al. Updated palliative care competencies for entry-to-practice and advanced-level nursing students: New resources for nursing faculty. J Prof Nurs 2022;42:250-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ferrell B, editor. Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. Palliative nursing manuals: Pediatric palliative care. New York: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Dahlin C, Coyne P, editors. Advanced practice palliative nursing. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2023.

- Thompson AL, Kentor RA. Introduction to the special issue on palliative care, end-of-life, and bereavement: Integrating psychology into pediatric palliative care. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol 2021;9:219-28. [Crossref]

- Kaye EC, Gattas M, Kiefer A, et al. Provision of Palliative and Hospice Care to Children in the Community: A Population Study of Hospice Nurses. J Pain Symptom Manage 2019;57:241-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wiener L, Devine KA, Thompson AL. Advances in pediatric psychooncology. Curr Opin Pediatr 2020;32:41-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pollock D, Peters MDJ, Khalil H, et al. Recommendations for the extraction, analysis, and presentation of results in scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth 2023;21:520-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kara M, Foster S, Cantrell K. Racial Disparities in the Provision of Pediatric Psychosocial End-of-Life Services: A Systematic Review. J Palliat Med 2022;25:1510-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]