The value and economic benefits of palliative care in primary care: an international perspective

This editorial highlights the rationale for primary care delivering palliative care (Box 1) (1): palliative care can reach all those in need if integrated in primary care services; primary care can identify people much earlier in the course of the illness than specialist palliative care so can prevent as well as limit suffering; and primary care can provide palliative care more cost-effectively in primary care than in other settings. Moreover, recent studies also suggest that palliative care can prevent many planned and unscheduled episodes of high-cost low-impact treatment if it is integrated in routine primary care services at diagnosis of a serious illness. It can also decrease catastrophic costs for patients in specially low-income settings.

| Primary palliative care is palliative care practiced by primary health care workers, who are the principal providers of integrated health care for people in local communities throughout their life. It includes early identification and triggering of palliative care as part of integrated and holistic chronic disease management, collaborating with specialist palliative care services where they exist, and strengthening underlying professional capabilities in primary care (1) |

The overall value and rationale for developing palliative care in primary care and important policy developments

Yearly, around 60 million people experience serious health-related suffering (SHS) (2). Suffering is health-related when it cannot be relieved without professional intervention and when it compromises physical, social, spiritual, and/or emotional functioning (2). Projections indicate that this trend will continue to 2060—affecting largely low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), especially due to cancer, cerebrovascular disease, lunge disease, and dementia (3).

The groundbreaking resolution on palliative care “Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course” (WHA67.19) was unanimously approved by all member states at the World Health Assembly in 2014 (4); it emphasizes the urgent need to include palliation across the continuum of care, especially at the primary care level (4). In 2018, the Member States reaffirmed their commitment to strengthening primary health care and explicitly included palliative care (5). In 2019, the political declaration on Universal Health Coverage (UHC) recognized palliative care as an integral part of the health service (6), which means without palliative care there is no UHC. Palliative care became part of Essential Universal Coverage Packages (7). Palliative care is not a luxury or a privilege, but it is a basic right for all—as stated by the Human Rights Council (8)—and an ethical duty for health care systems (4).

Palliative Care has developed and grown in most countries as a specialty, although there are some notable exceptions such as Panama, but there will never be enough specialist palliative care for all, and in fact it is not needed (9). Specialist professionals are necessary for complex situations and support, but generalists can ably cope with 75% of patients, and are moreover able to intervene earlier in the illness trajectory (9). Most health-related suffering can be prevented and relieved by primary health care workers, who are the principal providers of integrated health care for people in local communities throughout their life especially in LMICs (2).

Primary palliative care starts with the key first step of early identification of people in need and triggering integrated and holistic chronic disease management, collaborating with specialist palliative care services where they exist, and strengthening underlying professional capabilities and compassionate care in primary care (1). To do this, they need training in how to deliver palliative care in the community and to have access to inexpensive, safe and effective essential medicines and equipment (2). Knowledge on communications skills, self-care, and symptom control are resources for dealing with patients with serious diagnoses, reducing their stress and improving the quality of care. Families and local communities provide most care for people with palliative care need (10). Primary health care workers provide care for the whole family and are often leaders in these communities and together with them can provide compassionate care. Primary care is aptly placed to provide palliative care because most patients who could benefit of palliative care reside at home and cannot easily travel beyond their communities, and most people also prefer to die there with an adequate care (11).

However, global provision of primary palliative care remains underdeveloped (12). The access to essential medicines for palliative care and pain medicines, especially opioids, is a major barrier. The Special Session of the United Nation General Assemble (UNGASS) suggest specific recommendation for countries for the improvement of the access of opioid analgesic for medical proposal (13). The Lancet Commission on Pain and Palliative Care have costed an affordable essential package of palliative care medication and equipment which should be available in primary care. However, lack of understanding about palliative care among national policymakers, health professionals and in the community is another important barrier to the development and use of palliative care. This reflects a lack of alignment between the needs, demands and the national structures of the health and social care systems, staff education and training.

Value of primary palliative care to health systems, patients and to public health

Evidence increasingly shows micro and macroeconomic benefits of the integration of palliative care in improving quality and sometimes even length of life while decreasing costs (14). During the last year of life due to medical costs, hospitalization and admissions to intense care units as well sometimes futile treatments, high costs are generated for the health care system (15-18), but also for the patients and their family (19).

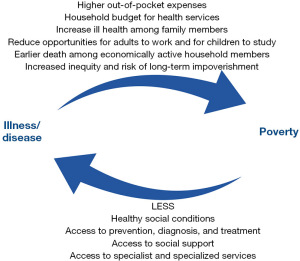

Literature reviews have demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of palliative care (20,21). By integrating palliative care, the health care services can profit by reducing overcrowding services and the cost for the health care system, especially in low-resource settings (22). Cost savings are due to reducing repeat hospital admission through improved pain and symptom control as well as reduction of aggressive and futile treatments. Out-of-pocket cost at the end of life represents an important source of health expenditures and impoverishment, especially in LMICs (23) due to direct and indirect costs. This can lead to a medical poverty trap (Figure 1), which obviates the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) to reduce poverty and prevent financial hardship.

If patients and carers receive adequate care at home, most prefer to live and die there, which may reduce their financial distress (24,25). The improvement of quality of life and symptom control patients experience there increases functionality and mobility and enable patients and caregivers to return to social activities, participating in family, social, and community life and even to return to work. The financial protection and better caregiver and family quality of life may have positive effects on the experiences and in family members’ physical, emotional, and mental well-being (26). Also the access to grief support may promote resilience and well-being during bereavement (27).

The introduction of palliative care has shown reduction in poverty through reducing households’ expenditure on medical care, assisting patients and their family members to receive government benefits, and enabling some family members and patients to work again (28). Specifically in a low-income country as Malawi, a prospective cohort study of patients with advanced cancer found that ‘catastrophic costs’, defined as 20% or more of total household income, sale of assets and loans taken out (dissaving) were common, and that palliative care provision significantly reduced dissaving (26).

However, palliative care service provision requires investment to set up and maintain, including staff, education, and medication as described in the Essential Package for Palliative Care (2,7). Calculations of the costs of expanding the package of palliative care services are published (2). But the investment will be more than returned, as a study demonstrated in Kenya that for every US dollars (USD) 10 spent on palliative care, the benefits are USD 27 (29). Primary health care can operationalize a public health approach to end-of-life care and improve the allocation and rational use of resources, in order to be used with a greater effect (30).

The assessment of the economic value of palliative care in primary care, the difficulties entailed and what may be needed to overcome these challenges and effect service developments

A recent international narrative review of 43 reviews about the evidence of the economic value of end-of-life and palliative care interventions assessed the evidence across various settings (31). It found that most evidence on cost-effectiveness relates to home-based settings and that it offers substantial savings to the health systems by reducing aggressive medicalization at the end of life and improved patient and caregiver outcomes. The evidence across other settings was inconsistent. Interventions in primary care such as advance care planning, and day-care tended to occur earlier in the course of the illness, thus information on timing in relation to death would be useful to more fully understand resource implications. This review also called for quasi-experimental designs as randomized controlled trial are rarely feasible in this area. The MORECare Statement on good research practice generated by a synthesis of transparent expert consultations and systematic reviews in increasingly cited concerning palliative care intervention (32). On the clinical side, it is important to study if generalists can deliver interventions as well as specialists. This is important as most studies of integrating palliative care with oncology (14) or other medical specialities such as cardiology have been with specialist palliative care. A recent study integrating oncology with primary care through routinizing advance care planning shows that such interventions are feasible and acceptable with patients (33).

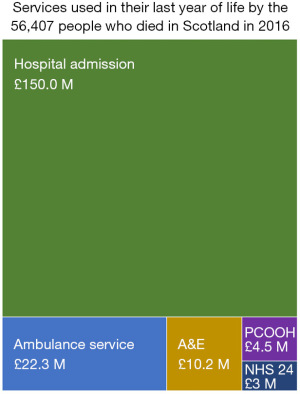

May and Cassel have described various limitations to studies assessing individual outcomes as palliative care is such a complex intervention (34). To combat this, researchers in Scotland (including S.A.M.) adopted a public health or “whole-systems” approach to understand the wider context. They conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of five national datasets with application of standard UK costings of people who died in Scotland in 2016 (35). This allowed the researchers to identify and cost the continuous unscheduled care pathways as patients passed from telephone advice, to primary care contacts, ambulance service, emergency departments, and some were admitted. One outstanding finding was that the cost of providing services in the community was estimated as 3.9% of total costs, despite handling most of the service provision (Figure 2). Patients with organ failure contacted the ambulance service more frequently than those with cancer or frailty. A parallel qualitative study revealed that many patients with heart failure who were admitted would have preferred an assessment at home rather than having to attend an emergency department. But interviews with service providers revealed that primary care was not adequately resourced to enable timely review in the community, so sometimes an ambulance was sent unnecessarily, and the patient was usually admitted. This suggests that a small shift in resources from hospital to primary care would be high value to patients and carers and cost-effective (36). Thus, having qualitative as well as quantitate data allowed a better understanding and evidence-based recommendations.

This mixed-methods study using a systems-based approach to describe and evaluate holistic care illustrates the values of this approach rather than simply looking at one of two outcome indicators from one setting (36). The study innovatively identified how patients with palliative care needs, even when they had not been recognized as such clinically interacted and used unscheduled care. Thus, it identified unmet needs in patients with progressive serious diseases within their last year of life, and how health services dealt with these as they progressed through their last year of life.

Despite this being a systems-based study, it did not include social care data or data from planned hospital admissions, aspects which should be explored in future studies. Noticeably, the only big data source that included an indicator for palliative care provision was unscheduled primary care data. Routine collection of palliative care indicators in all community and hospital services needs to be introduced to allow more effective studies to be undertaken.

Finally, early recruitment of people to “palliative care” studies is difficult due to clinician gate-keeping. We have found in Scotland that it is helpful to label the studies detailing what the intervention is doing e.g., “anticipatory care planning”, rather than “palliative care” which is a term that is sadly still stigmatized by patients and carers, and this has helped with identification and recruitment of patients. This reflects the vocabulary that family physicians are actually using in their daily practice and found acceptable with patients.

Call for action and steps to develop high-impact low-cost evidence-based palliative care for all in primary care

We have an ethical and moral duty to respond to the suffering of millions of people who could benefit from palliative care. Policies are in place internationally and we already know how to alleviate much suffering due to all serious diseases. But implementation is still patchy (37). About 14% of people who need it currently receive palliative care (38), which leaves around 50 million living and dying with unrelieved suffering, the majority, but by no means all of them in LMICs. This neglect of access to palliative care and pain relief constitutes cruel, inhuman treatment and punishment (39).

Countries should review the evidence supporting micro- and macro-economic benefits of palliative care approach in primary care and take the steps to guarantee access to all components in the Essential Package for Palliative Care to everyone and everywhere in the country. These steps include advocacy for national policies, strengthening of palliative care integration in the national health care system, education for providers and accessible and affordable medications in every country. This would result in cost savings to households and the health system, and reduce inequalities and improve the quality of care.

A Toolkit, generated by international leaders from many countries, for the development of palliative care in primary care is available in several language (12,40). This could be used to help drive appropriate policy, educational, service development, and medication availability developments in different regions and countries. Also, the Supportive & Palliative Care Indicator Tool (SPICT®) including a version specially designed for low-income settings (SPICT-LIS) is a screening tool for nurses and doctors to identify people for early palliative care. SPICT has been culturally adapted, validated, and translated into 14 different languages to address the common barrier to early identification (41). It can help clinicians to trigger holistic care (42) and have conversations with patients and start anticipatory and advance care planning. Indeed advance care planning is an intervention where there is increasing evidence of economic value to the care system (15). Such plans must be communicated with all involved in unscheduled and emergency care which can prevent avoidable admissions (35,43). There are various cultural, religious, and social factors what should be considered to ensure these conversations are helpful for patients, as well as enough time to start and continue the dialogue (43). We need to work together towards the integration of palliative care into primary health care, enabling everybody to access adequate care when and where they need it across all ages (including children).

At the same time, innovative studies must be undertaken in multiple contexts to ensure evidence-based interventions fit with different models of primary care. These studies should take a public health and systems-based approach and should explore the needs and services for people in the last years of life to see how palliative care delivered by specialists, generalists in hospital and in primary care, and local communities can bring high-value low-cost care to all people wherever they live and from whichever life-limiting condition they suffer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Daniel Munday for his valuable comments.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Claudia Fischer) for the series “Value of Palliative Care” published in Annals of Palliative Medicine. The article has undergone external peer review.

Peer Review File: Available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-270/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://apm.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/apm-23-270/coif). The series “Value of Palliative Care” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. T.P. is the co-chair of the Reference Group Primary Palliative Care of the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) (unpaid). S.A.M. is the Founder and Chair of the Reference Group Primary Palliative Care until 2022 (unpaid), and as a Professor of Primary Palliative Care, he has been researcher, advocate and enthusiast for the benefits of palliative care in primary care, which he believes include economic benefits. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Munday D, Boyd K, Jeba J, et al. Defining primary palliative care for universal health coverage. Lancet 2019;394:621-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Knaul FM, Farmer PE, Krakauer EL, et al. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief-an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2018;391:1391-454. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sleeman KE, de Brito M, Etkind S, et al. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e883-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Assembly. Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. 2014. Accessed Feb 22, 2023. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/162863/A67_R19-en.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- World Health Organization. Declaration of Astana: Global Conference on Primary Health Care. 2018. Accessed March 01, 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health/declaration/gcphc-declaration.pdf-

- United Nations. Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage “Universal health coverage: moving together to build a healthier world”. 2019. Accessed Feb 22, 2023. Available online: https://www.un.org/pga/73/wp-content/uploads/sites/53/2019/07/FINAL-draft-UHC-Political-Declaration.pdf

- Krakauer EL, Kwete X, Verguet S, et al. Palliative Care and Pain Control. In: Jamison DT, Gelband H, Horton S, et al., editors. Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty. 3rd ed. Washington: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2017.

- United Nations. Human Rights Council Forty-Eighth Session. Human rights of older persons. A/HRC/RES/48/3. 2021. Accessed March 01, 2024. Available online: https://undocs.org/Home/Mobile?FinalSymbol=A%2FHRC%2FRES%2F48%2F3&Language=E&DeviceType=Desktop&LangRequested=False

- Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care--creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stjernswärd J. Palliative care: the public health strategy. J Public Health Policy 2007;28:42-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Why palliative care is an essential function of primary health care. 2018. Accessed March 01, 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/primary-health-care-conference/palliative.pdf

- Murray SA, Firth A, Schneider N, et al. Promoting palliative care in the community: production of the primary palliative care toolkit by the European Association of Palliative Care Taskforce in primary palliative care. Palliat Med 2015;29:101-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Outcome document of the 2016 United Nations General Assembly Special Session on the world drug problem. 2016. Accessed March 01, 2024. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/documents/postungass2016/outcome/V1603301-E.pdf

- Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luta X, Diernberger K, Bowden J, et al. Healthcare trajectories and costs in the last year of life: a retrospective primary care and hospital analysis. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Polder JJ, Barendregt JJ, van Oers H. Health care costs in the last year of life--the Dutch experience. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:1720-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scott OW, Gott M, Edlin R, et al. Costs of inpatient hospitalisations in the last year of life in older New Zealanders: a cohort study. BMC Geriatr 2021;21:514. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Normand C, May P, Cylus J. Health and social care near the end of life: Can policies reduce costs and improve outcomes? Eur J Public Health 2021;31:iii212. [Crossref]

- Boby JM, Rajappa S, Mathew A. Financial toxicity in cancer care in India: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol 2021;22:e541-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith S, Brick A, O'Hara S, et al. Evidence on the cost and cost-effectiveness of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat Med 2014;28:130-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parackal A, Ramamoorthi K, Tarride JE. Economic Evaluation of Palliative Care Interventions: A Review of the Evolution of Methods From 2011 to 2019. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2022;39:108-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anderson RE, Grant L. What is the value of palliative care provision in low-resource settings? BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000139. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reid E, Ghoshal A, Khalil A, et al. Out-of-pocket costs near end of life in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. PLOS Glob Public Health 2022;2:e0000005. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sedhom R, MacNabb L, Smith TJ, et al. How palliative care teams can mitigate financial toxicity in cancer care. Support Care Cancer 2021;29:6175-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al. Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32:1143-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jane Bates M, Gordon MRP, Gordon SB, et al. Palliative care and catastrophic costs in Malawi after a diagnosis of advanced cancer: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 2021;9:e1750-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harrop E, Scott H, Sivell S, et al. Coping and wellbeing in bereavement: two core outcomes for evaluating bereavement support in palliative care. BMC Palliat Care 2020;19:29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ratcliff C, Thyle A, Duomai S, et al. Poverty Reduction in India through Palliative Care: A Pilot Project. Indian J Palliat Care 2017;23:41-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Namisango E. Cost of end-of-life care. The economics of palliative care. 2022. Webinar an 12th December. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0yiumJMX_Jk EAPC

- Normand C. Economic perspective on public health approaches to palliative care. In: Abel J, Kellehear A, editors. Oxford Textbook of Public Health Palliative Care. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2022:255-61.

- Luta X, Ottino B, Hall P, et al. Evidence on the economic value of end-of-life and palliative care interventions: a narrative review of reviews. BMC Palliat Care 2021;20:89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Higginson IJ, Evans CJ, Grande G, et al. Evaluating complex interventions in end of life care: the MORECare statement on good practice generated by a synthesis of transparent expert consultations and systematic reviews. BMC Med 2013;11:111. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Canny A, Mason B, Stephen J, et al. Advance care planning in primary care for patients with gastrointestinal cancer: feasibility randomised trial. Br J Gen Pract 2022;72:e571-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- May P, Cassel JB. Economic outcomes in palliative and end-of-life care: current state of affairs. Ann Palliat Med 2018;7:S244-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mason B, Kerssens JJ, Stoddart A, et al. Unscheduled and out-of-hours care for people in their last year of life: a retrospective cohort analysis of national datasets. BMJ Open 2020;10:e041888. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mason B, Carduff E, Laidlaw S, et al. Integrating lived experiences of out-of-hours health services for people with palliative and end-of-life care needs with national datasets for people dying in Scotland in 2016: A mixed methods, multi-stage design. Palliat Med 2022;36:478-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murray S, Amblàs J. Palliative care is increasing, but curative care is growing even faster in the last months of life. Br J Gen Pract 2021;71:410-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Palliative care. Key facts. 2020. Accessed Feb 22, 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care

- Nowak M. Human Rights Council 70th Session. Report of the Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Manfred Nowak. 2009. Accessed Feb 22, 2023. Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/647301?ln=en#record-files-collapse-header

- EAPC. Primary Care. Toolkit. 2019. Accessed Feb 24, 2023. Available online: https://www.eapcnet.eu/eapc-groups/reference/primary-care/

- University of Edinburgh. Supportive & Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT™). 2023. Accessed Feb 24, 2023. Available online: https://www.spict.org.uk/

- Robinson J, Frey R, Gibbs G, et al. The contribution of generalist community nursing to palliative care: a retrospective case note review. Int J Palliat Nurs 2023;29:75-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Finucane AM, Davydaitis D, Horseman Z, et al. Electronic care coordination systems for people with advanced progressive illness: a mixed-methods evaluation in Scottish primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2019;70:e20-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]