CanSupport: a model for home-based palliative care delivery in India

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual” (1). In 2014, the WHO and World Palliative Care Alliance released a global atlas to assess the provision of palliative care, which reported that only 14% of those in need are receiving palliative care worldwide. Not surprisingly, 78% of the unmet need was in low- or middle-income countries (2). As the burden of chronic illness rises in these countries, the gaps in palliative care will continue to rise unless efforts are made to expand access to palliative care services.

In India, there are an estimated 6 million people per year in need of palliative care (3). The Economist Intelligence Unit, an independent research organization, rated India last out of 40 countries on a Quality of Death Index, which took into account several factors, including cost, quality, availability, and awareness of end of life care (4). Kerala is the only state in India that has a palliative care policy and its state government provides funding for community-based palliative care services (3). As a result, approximately 90% of India’s palliative care services are located in Kerala, a state that has only 3% of the country’s population (5). Throughout the rest of the country, the provision of palliative care is largely managed by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), which are primarily based in major cities and regional cancer centers (3). With 7 out of 10 people in India living in rural locations, this structure has left a large proportion of the population without any access to palliative care (5). A 2008 overview of palliative care capacity showed that only 16 of Indian 35 states and union territories had any palliative care services (6). In the city of Delhi, there are only 3 palliative care providers an inpatient hospice and two homecare service providers to serve 35 million people in the city (6).

In addition to the disparities in access to palliative care throughout India, strict regulations on opiate supply have left such drugs largely unavailable for use in pain relief. The Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (NDPS) Act of 1985, passed as an attempt to limit misuse and diversion of narcotics, enacted complex licensing requirements for the procurement and distribution of morphine. This legislation resulted in a 97% decrease in the use of morphine for medical care in India from the time the Act was approved to a low of 18 kg of morphine in 1997 (7). According to one report, fewer than 3% of cancer patients in India have access to adequate pain relief (8). In 2014, an amendment to the NDPS Act was passed that relaxed regulations on obtaining opiates, a change that will hopefully increase the availability of these medications for patients in need of palliation. However, because opiates have been largely unavailable for use in medical care for the past 30 years, health care professionals are unfamiliar with the safe and appropriate prescription of these medications at the end of life, and training in palliative care is limited.

In this paper, we describe a model for home-based palliative care that is used by CanSupport, a non-governmental organization, to serve patients in the area around Delhi, India. CanSupport has been providing free, cost-effective palliative care services to patients since 1997 (9). Care is delivered by multidisciplinary teams composed of doctors, nurses, and social workers, who make home visits and respond to phone calls from caregivers. CanSupport follows a holistic model of care, managing symptoms and pain while also addressing the emotional and spiritual well-being of patients and their families. By analyzing and presenting the model of care provided by CanSupport, we hope to raise awareness of the need for palliative care in developing countries and to highlight the potential of home-based palliative care delivery.

Methods

All patients were consented for the care provided by CanSupport, including the administration of questionnaires and validated tools for symptom assessment. We retrospectively reviewed patient demographics, services provided, and questionnaire responses for CanSupport patients treated from 2009–2010. On initiation of care and at each visit, questionnaires and validated tools were administered to patients to assess pain and other symptoms. Physical pain was assessed via a 0–10 Numeric Pain Rating Scale and psychosocial, spiritual, and emotional pain with the Pain Self-Efficacy Scale (PSES) (10,11). Symptom severity was assessed with the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS) (12). In addition, patients were evaluated with the Karnofsky Performance Scale (13).

To assess the patient’s emotional state, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Distress Thermometer was used (14). If a score greater than 4 was reported on the Distress Thermometer, patients were administered the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12) to further evaluate their mental state (15). In addition, a Psychosocial Assessment was done, which gathered information about spiritual, social, and emotional issues, in addition to patient awareness about their illness.

Some of the data was obtained from direct discussion with CanSupport staff members, mostly information about team operations and costs per patient.

Results

CanSupport operates out of 13 centers around the Delhi area (South, West, East, Northwest, Northeast, Bawana, Gurgaon, Faridabad, Ghazibad, Noida, Old Delhi, and Tughlakabad). The current staff includes 24 multidisciplinary teams, each consisting of a physician, nurse, and counselor, who are required to receive training in the provision of palliative care. Each team covers a 25 (urban area) to 35 km (semi-urban area) radius around their center. The team makes daily home visits according to a follow-up schedule of their assigned patients. Most teams (on average) are following 50–60 patients at any given time. CanSupport has a relationship with the Institute Rotary Cancer Hospital of the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (IRCH/AIIMS) and patients are often referred for home care services from the hospital.

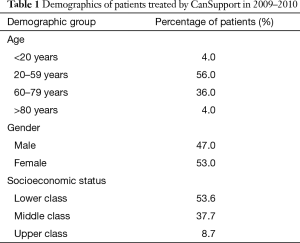

In 2009–2010, the CanSupport teams provided home-based palliative care to 746 patients (Table 1). In terms of socioeconomic status, the majority of these patients were lower class (54%) or middle class (38%). Forty percent of patients were greater than 60 years old at the time care was initiated. Mean duration of care was 1–2 months. Ten percent of patients received home care for 1–4 years and an additional 1% for greater than 4 years. Many patients come to the city and stay with relatives while they are undergoing treatment and are initially referred to CanSupport during this time. When patients return to their home village, CanSupport stays in contact with the patient and family by telephone, and will often continue to provide pain medication refills.

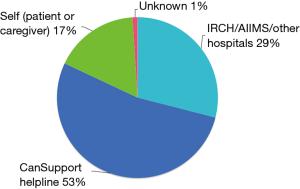

Full table

The most common symptom for initial referral to CanSupport was pain, followed by shortness of breath, vomiting, loss of appetite, fatigue, becoming bed-ridden, and delirium. 53% were referred by calling the CanSupport Helpline, which is staffed by a counselor during business hours to take referrals and provide families with additional information (Figure 1). An additional 17% of patients were referred directly by themselves or a caregiver. The rest of the patients (29%) were referred by IRCH/AIIMS or other hospitals in the area. Though overall awareness in the community about palliative care is reported to be poor, CanSupport promotes its services to patients through advertisements in pharmacies, general practitioner clinics, hospitals, and online and with posters in commonly visited areas, such as temples and markets.

CanSupport teams made an average of 10 visits per patient during the year 2009–2010. During the first home visit, the patient’s history is taken and medical, nursing, and psychosocial needs are reviewed. Medical and nursing issues are addressed at that visit, with counseling typically reserved for subsequent visits. Based on symptoms at presentation and state of disease, patients are determined to be high need (seen weekly), medium need (seen every 15 days), or low need (seen once monthly). With changes in symptoms and disease progression, the frequency of home visits can change, and sometimes patients may be seen up to 2–3 times per week if needed. During home visits, caregivers are taught to provide simple nursing tasks, such as wound care, for the patient. Simple procedures, such as insertion of nasogastric tubes or Foley catheters, are managed by the nurse during these visits. In addition, procedures such as thoracentesis or paracentesis can be done at home if the patient is unable to go to the hospital. The CanSupport team will liaison with the patient’s family physician to coordinate care, which becomes especially important when patients return to their home village.

Of the 609 patients who had an initial visit with CanSupport in 2009–2010, 80% (n=487) were aware of their diagnosis at their first visit. At each visit, the physician (or less frequently, the nurse) on the team administered the pain and symptom assessment instruments described in the above. Morphine was prescribed if needed; 31% of patients (n=230) received morphine during 2009–2010. Certain injectable medications can be administered by the team at home, including metoclopramide, ondansetron, ranitidine, dexamethasone, hyoscine butylbromide, haloperidol, lorazepam, tramadol, and diclofenac sodium. A majority of patients report improvement in pain and other symptoms after the first home visit. Of the 550 patients who had their first home visit in 2009–2010, 223 (41%) reported no pain or mild pain (0–3 on visual pain scale) at their first visit and 85 (15%) reported severe pain (7-10). After 2 visits, 433 (79%) reported no pain or mild pain and 36 (7%) reported severe pain.

Patients are given an emergency phone line where they can reach a physician or nurse at any time. CanSupport staff responded to 2,619 calls from patients and their caregivers during the year, an average of 3.5 calls per patient. The most common reasons for calls were worsening pain, intractable vomiting, and delirium. Families are often given additional doses of medications in anticipation of symptom recurrence. If the issue cannot be managed over the phone, the team will either visit the patient that day or refer the patient to the hospital for calls made at night or on weekends. Rarely, the patient is immediately referred to the hospital (e.g., concern for neutropenic fever).

Thirty patients (6%) were hospitalized during the 2009–2010 year for difficult symptom management. The most common reasons for hospitalization were uncontrolled pain, breathlessness, and delirium. Approximately 80% of referrals to the hospital were made by the CanSupport team. Of the 20% of cases where the family takes the patient to the hospital themselves, it is often after the first 1–2 home visits by CanSupport, before the team has formed a close relationship with the patient and their family. Twenty five patients (3%) were referred to hospice during the 2009–2010 year.

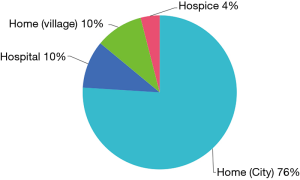

A total of 514 patient deaths occurred during the 2009–2010 year. Of those, the majority (n=442, 86%) died at home, 391 at their residence in the city (76%) and 51 after returning to their home village (10%) (Figure 2). Of the remaining patients, 52 died in the hospital (10%) and 20 died at a hospice facility (3.8%). Home deaths for patients >60 years old do not require certification; instead, the family receives a slip from the cremation ground, which they can use to get a death certificate from the municipality. The preferred place of death is discussed with the patient or their caregiver at the end of life and the appropriate arrangements are made. The majority of patients wish to die at home.

The families of 471 of the deceased patients received a bereavement visit by the team (91.6%). The family automatically qualifies for a bereavement visit or call if the patient received more than 3 home visits, but they are also available by request for those who received fewer visits. The initial bereavement visit is typically scheduled after mourning rituals are complete (for Hindu patients, 13 days after death, for other religions ~10 days). Subsequent visits or calls were made if there appeared to be a need for ongoing support, such as those who lost a child or spouse. In these circumstances, bereavement counseling was typically provided up to 6 months, or occasionally longer, depending on need.

Caregiver satisfaction with CanSupport is assessed with a post-bereavement questionnaire that is administered 6–12 weeks after a patient’s death. Feedback is provided by 70–75% of those who receive bereavement visits or calls. The satisfaction rate in 2009–2010 was 90%. If any caregivers report that they are not satisfied with CanSupport’s care, the team tries to assess the reason why.

Funding for services comes from individual donations and grants from trusts, foundations, private companies, and units in the public sector. The average cost per patient is Rs. 9,000–10,000. The breakdown of cost is: 70% salaries, 10% transport, 10% center operational costs, 5% medications including morphine, 5% miscellaneous. All services are free of charge for patients.

Discussion

There has recently been on focus on the importance of integrating palliative care into health care systems, with a 2014 WHO publication defining the gaps between need and access worldwide, which are greatest in lower- and middle-income countries (1). Though the first palliative care centers in India were established in the late 1980s and early 1990s, there has been little progress to expand the delivery of palliative care to the majority of the country. One barrier to providing effective palliative care has been the scarcity of opiate supply and inexperience amongst providers with its use in palliation, a consequence of the strict licensing requirements imposed by the 1985 NDPS Act. In addition, training in palliative care within the country is limited, with only 6 institutions offering a one-year fellowship program for physicians (5). Another significant barrier to expanding access to palliative care in India is the lack of central governmental policy and financial support. Many areas of India have no access to palliative care, while pockets of the country are served by NGOs that operate independently or in conjunction with hospitals. CanSupport is one such NGO that provides home-based palliative care in Delhi, serving both hospital- and self-referred patients. We report on its impact here to describe a model of palliative care delivery that has had success in the developing world.

Seen as a “beacon of hope”, the palliative care model in the state of Kerala stands in stark contrast to the state of palliative service delivery within the rest of India (5). Formed through the collaboration of 4 NGOs in 1999, the Neighborhood Network in Palliative Care (NNPC) extends throughout most of the state and is rooted in the notion of community involvement. Palliative care programs within this network now account for 90% of those operating within India and Kerala is the only state where palliative care is integrated into the public health system (5). This expansion of services would not have been possible without significant involvement from local self-government institutions (LSGIs), which forged a major campaign in 2007 to increase the presence of palliative care. By 2008, the state government had formed a pain and palliative care policy that helped to shape future palliative care development (5). Helping to organize, implement and oversee palliative care throughout the state, LSGIs have become the backbone of service delivery facilitation. At the heart of this delivery has been a workforce primarily comprised of community volunteers, who are engaged in all aspects of palliative care units within the state (5).

Unlike in Kerala, where home care delivery has “revolutionized” the state’s healthcare system, palliative care at the institutional level does not tend to incorporate the context of the patient at home (5). As a result, both family and community members are incorporated to a far smaller extent. CanSupport differs from both the Kerala system and institution-based care by providing a model of home-based palliative care in which trained specialized staff delivers services rather than community volunteers (9). The founder of CanSupport, Harmala Gupta, continues to highlight this contrast by raising concerns about the quality of care delivered by such volunteers versus trained home care teams comprised of doctors, nurses, and counselors (3). CanSupport allows for self-referral for palliative care services from patients who feel that they may be in need, while also maintaining a relationship with AIIMS for referrals and for coordination of medical care. Other delivery models seem to have adopted a similar hybrid approach to palliative care delivery. Guwahati Pain and Palliative Care Society in Assam, North East India operates through a combination of clinical staff and community volunteers, while the Chandigarh Palliative Care service in North India fosters continuity between outpatient and home based care (3). The fact that more of CanSupport’s patients were self-referred than referred by hospitals speaks to the scale of the palliative care need outside of the health care system.

In recent years, home-based care has been increasingly pursued as an opportunity for health care expansion in India and is a model that is well-suited for the delivery of palliative care. When terminally ill patients require ongoing management of pain and other symptoms, but do not have acute care needs requiring hospitalization, home care allows them to remain comfortable while reducing the burden of care on the family. A survey of Indians found that 83% of respondents would prefer to die at home rather than in a hospital or care facility (9). In addition, studies have shown that home care decreases the number of hospital visits and deaths that occur in the hospital (6), potentially saving families, especially those in rural areas, significant time and money. Home care saves patients and their families the cost and time of travel to and from the hospital or clinic and eliminates the costs of an acute hospital stay. The majority of CanSupport’s patients are lower or middle class and socio-economic rehabilitation is one of their priorities. Staffs are available by phone for caregivers and patients, allowing for questions to be answered and medical issues to be triaged remotely. Previous publications have shown that over 90% of patients and caregivers were satisfied with the care they received from CanSupport (9,16), which is consistent with the results of this study.

As palliative care development continues in low- to middle-income countries, the challenges that organizations such as CanSupport have faced can serve as valuable lessons. One of CanSupport’s current goals is to improve communication and information exchange with cancer centers and oncologists. An ongoing challenge is to educate physicians about the role of palliative care and how they can identify patients who would benefit from referral. In addition, due to the lack of government and private funding, the inconsistent source of funding from year to year remains a concern. Finally, as the organization expands to serve more patients, more physicians and nurses will be needed who are willing to be trained in palliative care and who have experience with prescribing opiates.

CanSupport is nearing its twentieth year of providing palliative care services to the area of Delhi. Over the course of these two decades, it has developed a sustainable model for delivering home-based end of life care in India. Its team-based approach allows for the coordination of care to a growing number of patients and families. Though CanSupport is able to serve only a fraction of the country’s population in need, its ongoing success highlights the impact that quality, convenient, and cost-effective palliative care can have in the developing world.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Mrs. Harmala Gupta, the Founder-President of CanSupport.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This study was exempt from Institutional Review Board approval since no patient Protected Health Information was required to describe this model of care delivery. All patients were consented for care and procedures used by CanSupport and consented to collection of the data presented in this manuscript.

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: http://www.who.int/hiv/topics/palliative/PalliativeCare/en/

- Connor SR, Bermedo MC, editors. WHO global atlas of palliative care at the end of life, 2014. Available online: http://www.who.int/nmh/Global_Atlas_of_Palliative_Care.pdf

- Khosla D, Patel FD, Sharma SC. Palliative care in India: current progress and future needs. Indian J Palliat Care 2012;18:149-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Economist Intelligence Unit. The quality of death: ranking end-of-life care across the world. Available online: http://graphics.eiu.com/upload/eb/qualityofdeath.pdf

- Kumar S. Models of delivering palliative and end-of-life care in India. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2013;7:216-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McDermott E, Selman L, Wright M, et al. Hospice and palliative care development in India: a multimethod review of services and experiences. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35:583-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajagopal MR, Joranson DE, Gilson AM. Medical use, misuse, and diversion of opioids in India. Lancet 2001;358:139-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- India: major breakthrough for pain patients. Available online: india-major-breakthrough-pain-patientshttp://www.hrw.org/news/2014/02/21

- Seow H, Brazil K, Sussman J, et al. Impact of community based, specialist palliative care teams on hospitalisations and emergency department visits late in life and hospital deaths: a pooled analysis. BMJ 2014;348:g3496. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCaffery M, Beebe A. Pain: clinical manual for nursing practice. Baltimore: V.V. Mosby Company, 1993.

- Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Pain 2007;11:153-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, et al. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 1991;7:6-9. [PubMed]

- Karnofsky DA, Burchenal JH. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In MacLeod CM, editor. Evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents. New York: Columbia University Press, 1949:191-205.

- The NCCN: Distress Management (Version 1.2008). 2007, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc, Accessed January 14, 2009. Available online: http://www.nccn.org

- Goldberg D. Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor, England: NFER Publishing, 1978.

- Banerjee P. The effect of homecare team visits in terminal cancer patients: role of health teams reaching patients homes. Indian J Palliat Care 2009;15:155-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]